BOTTER Than Ever

Check out the interview and photos below.

What has the Dutch mentality—its sometimes over-the-top down-to-earthness—brought about in you?

Rushemy Botter: I think our social circle is quite small. We don’t go to all the parties and the craziness. We like creating fashion but aren’t interested in all the stuff around it.

Lisi Herrebrugh: That can be hard sometimes. Business things can happen at those parties, but we’re choosing not to go there.

RB: We prefer to stay at home with our friends and families who don’t have anything to do with fashion. We can talk about everyday stuff, not just fashion. I mean, we’re not saving any children, you know.

LH: I also think it’s important to share our experiences with friends and family. If you can’t share it, what’s the point? We still have the same friends, and we love to go back to the Netherlands and just relax. Some say that’s naive—to not be apart of the fashion circus.

So you embraced the saying. I can also imagine that you wanted to rebel against it when you were younger?

RB: We’ve always been quite down to earth.

LH: People didn’t understand what we were doing at first. They all thought, "Why don’t you take a job? Get a mortgage? Why invest so much in something you don’t know it will deliver?" We had to struggle a bit with that mentality.

Yeah, I get it—it was until a few years ago that my mother still asked me, "When are you gonna get a job?" Even though I was doing okay.

RB: It’s a different generation. They see it differently. They don’t get that world—which I understand as well.

It’s hard enough to not say to yourself, "Why don’t I just get a job?" Let alone everyone around you saying the exact same thing.

LH: You have to believe in yourself.

RB: Our parents didn’t really know what we were doing until they saw the first show of Nina Ricci I think. Before that, it was really unclear. Alright, we make clothing. But who will wear it? What’s the use? Those sort of questions.

Who can afford it?

RB: Precisely, but then they get to see the show, the organisation, the public’s interest, the publications afterward, and then they think, “Oh, so this is serious.”

"Apparently, they do have a job."

RB: [Laughs] Indeed.

I see, and I’m not sure how to phrase this, an absurdity in your shows. So, I guess I want to talk about how you use, or view, absurdism.

LH: Hmm!

RB: I think it’s a way of communicating certain things without pushing it too much or forcing it. In our work, this approach works well, because when you approach things positively, more openly, you create a kind of conversation. You can interpret things the way you want to, instead of leaving a show with an emotion that’s forced on you.

LH: I think communicating emotion is super important for our work. Without it, it doesn’t have any meaning. Otherwise it’s just clothing. But to us, it’s really our diary, our emotion, our inspiration.

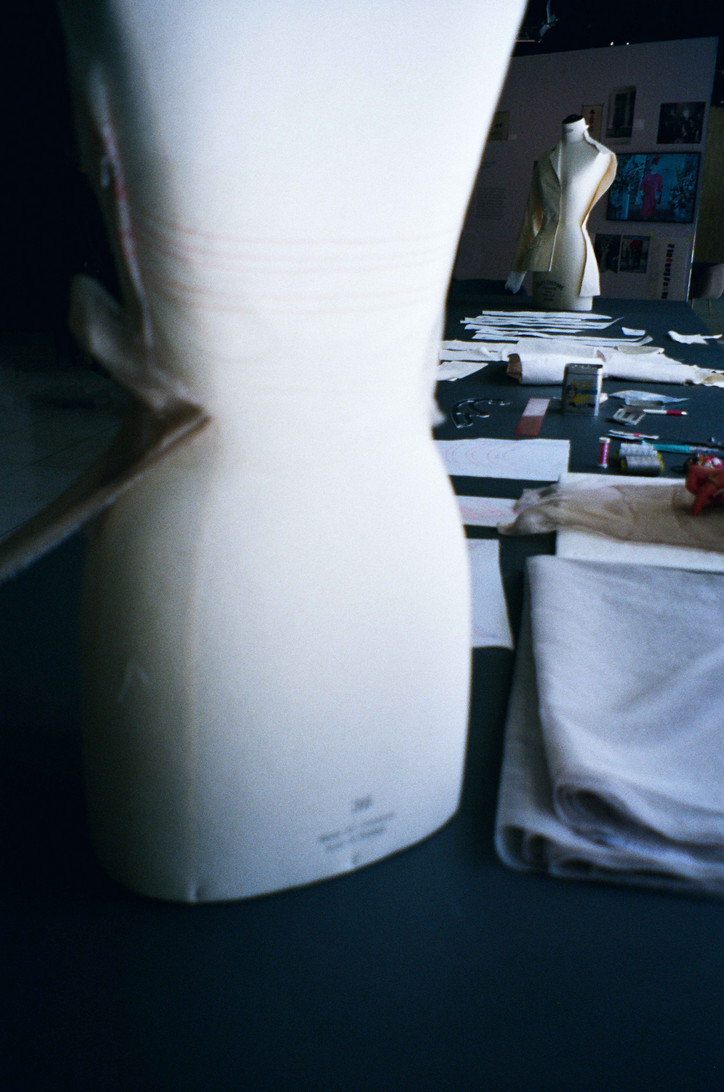

And clothing isn’t "clothing," but it’s the whole package, including styling, music, casting.

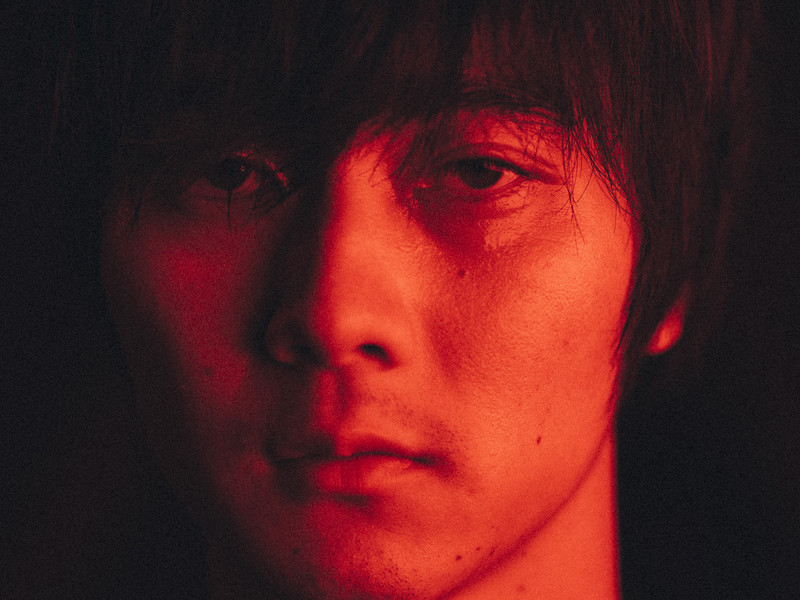

RB: It’s everything. Of course, clothing is just clothing, but we approach it from the silhouette. The model is a character—he could be from a book or a film. It’s a form of storytelling.

LH: I think that’s important—how to identify with someone. If you just look at it like "clothing," it’s gonna be very product-driven. We really want to tell a story with our work and link it with a clear character for people to identify with. I think that’s important for the long term—you really have to create something around it to stay relevant.

Is that maybe the difference between clothing and Fashion with capital F?

LH: I think so. That might be the difference. If you think of Walter van Beirendonck or Raf Simons, you immediately picture a person. And depending on your tastes, you’d want to wear it. It’s because of that extra something that you’re unable to capture. Like a kind of perfume? I don’t know to explain... It’s that mysterious thing you need in this industry.

RB: Yeah.

LH: That’s why it’s so difficult to capture. It’s something that happens over a period of time. Prada didn’t immediately get their man or woman; that happened over seasons. It’s a quest, a person you create in your head. What do they like? Can I link architecture? Which music fits? Which colors and words? It’s like writing a book, but it's much more visual.

It’s like a universe. I think you could say that the Big Brands all have a pretty clear universe. I suppose that’s why a lot of designers complain these days, because there’s no time to work on that universe anymore. They just need to deliver product. And what it does for a consumer, I guess... you want to be a part of that universe, and you just buy the sneakers.

LH: Commes des Garçons does this really well; they create this whole crazy world. and they stay relevant because of it. But it’s financed by that T-shirt with the heart logo. It’s such a difficult balance. As a young designer especially, you get treated much differently now than in the '80s. Then it was cool if you were experimental and if half of your collection was not manageable for production. Now, if you don’t end up in the shops, people don’t take you seriously. It makes it difficult for the young people to rise up.

The sales are taking over "the universe." Isn’t it difficult to work on two universes now? Or how do you know when something’s BOTTER and something’s Nina?

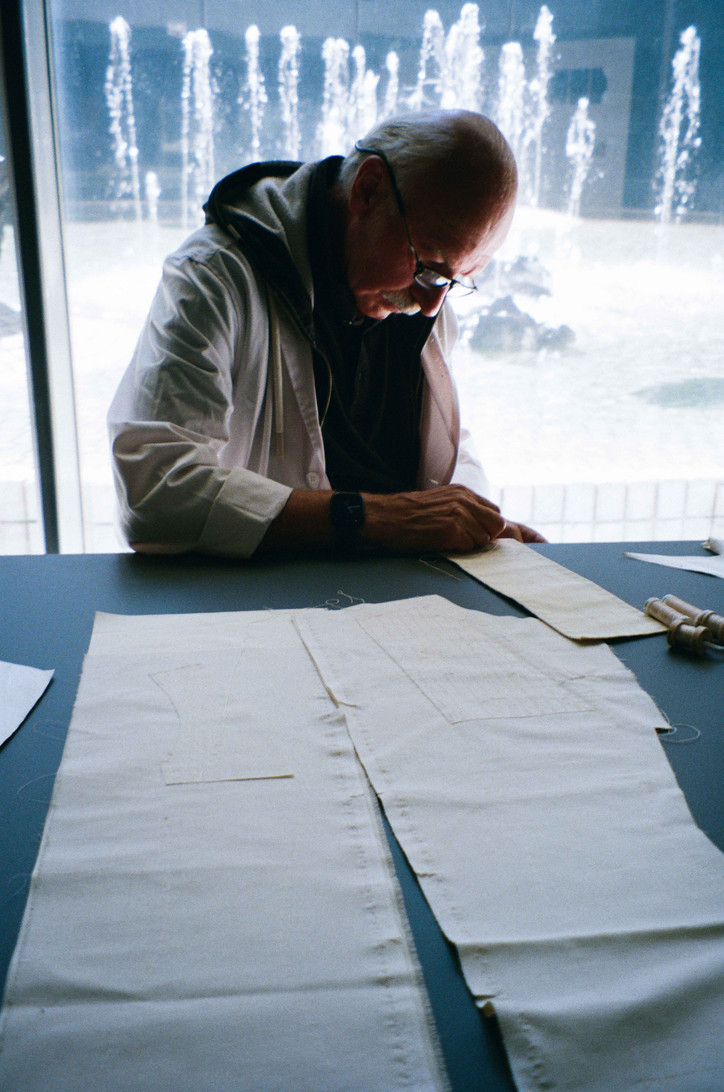

LH: That’s pretty clear now. For one thing, Nina is women’s and BOTTER is men’s. I think BOTTER is a bit more bold and spontaneous. Nina requires a different approach. It’s an established, luxurious French fashion house. It requires luxurious materials.

RB: Honestly, I think it was a bit difficult in the beginning. What exactly is BOTTER, and which ideas do you bring to Nina? We could use the same ideas for Nina, but we will deconstruct it much more, so you don’t get to see the concept so clearly. Two different approaches of working, but that’s what makes it so fun.

Is Nina more refined whereas BOTTER is more like slamming a fist on the table, and "here’s your silhouette"?

LH: Not really.

RB: Careful. I know what you mean. But BOTTER also has elegance.

LH: I think it’s in the process. For BOTTER, we like it’s directness in color, shape. The couture references will always have more easygoing pieces like the polo or the pellet jacket. With Nina. we’ll work on a shape until you’re pretty much unable to see its references. Both are refined, but Nina is more purified, I think.

Any tips for aspiring fashion designers?

RB: Cliche things, but they’re true. Trust yourself, don’t listen to others. We had a lot of folks, close to us, telling us we wouldn’t make it.

People actually told you, “This isn’t gonna happen?”

LH: Multiple.

RB: A lot of times.

Because they didn’t like it? Or didn’t understand?

RB: At some time, I just stopped telling people what I wanted to do. Now I just say, "I’m a fashion designer." But if I said, "I want to start BOTTER, go to Paris, have an atelier, maybe work as a head designer somewhere else..." People just didn’t believe I could.

LH: People told me I was living in a bubble. When Rushemy was still in college, I moved to Antwerp, and we continued working on BOTTER. But others told me I needed to work on my resume, that sort of thing.

RB: That’s so Dutch—having security. a nine-to-five job, a mortgage. If you say you do something creative, they don’t understand. You know what? Actually, I think they do bloody understand, because when you’re at a party, they sure know to find you when they need their pants hemmed.

I wouldn’t want to call it envy...

RB: Well, you almost would!

I don’t think it’s really envy. It’s also very Dutch to... I had to struggle with this myself as well, and I think you did too. You don’t want to go to parties and tell everyone what you are. You want your work to speak for itself.

RB: Yeah, yeah.

And it’s very Dutch to, when someone rises above the crowd a bit, to take him down a notch.

RB: Exactly. “Stay here, you.”

LH: And you end up bringing yourself down beforehand.

Like a self-defense mechanism.

LH: [Apologetically] “Fine, I’m a fashion designer, yeah. Fuck off.”

RB: [Laughs]