Andinos: Encounters in Cusco, Peru

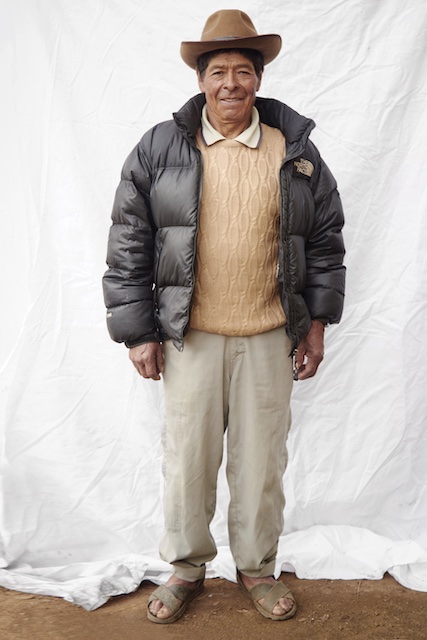

Bentín's first photobook, published by Rizzoli, depicts Cusco locals against their built environment, to reinforce an understanding of Los Andinos as they coincide with modernity and to remove the romantic versions of indigenous people pictured against their landscape and devoid of social context.

Adding another layer to his portrayals, Bentín collaborated with anthropologist Francesco D’Angelo to build a socio-anthropological photographic study offering commentary on the spatial modernity, social hierarchies and struggles against the idealized depiction of indigenous people.

Each image is accompanied by observations of nearby community members to guide readers through individual expression, and cultural modes of recognition. The paired images and commentary serve to articulate modernity in Andean society, creating new language and access points to go beyond documentation and bring life to representations of indigenous people.

Inspired by the popularity of Humans of New York, Bentín saw the resonance of connecting people across physical space. Focusing on commentary around ways of dressing, types of work, and occasions, Bentín creates universal touchstones to build recognition between readers and the subject of his images.

Read Bentín’s own observations in our interview below.

What does the publication of this book mean to you?

I started working on this project right after I left high school in Lima, Perú, and as I was moving to New York City to study photography. I really had no idea what I was doing, but my curiosity and determination to understand the realities of my country firsthand kept me going. Initially, this was only meant to be my thesis for The School of Visual Arts, but as the project moved forward, I started dreaming about the possibility of making it a book. Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine we would end up working with one of the most important editorials in the world, Rizzoli New York, and publish their first book on Peru by their first Peruvian author and one of their youngest authors ever published. I am beyond grateful for the trust that everyone at Rizzoli had on this project and me, especially my editor Martynka and our publisher Charles Miers.

Tell me a bit about the process of working with Francesco D'Angelo. How did that shape your work?

Francesco and I have known each other for a very long time, our families have always been close, but we had never worked together before. After my initial experience in the Andes in 2016, I had thousands of questions, crazy ideas in mind, and a lot of energy, so my first thought was to speak with Francesco. At the time, Francesco was living in a community in Maras, Cusco, as the anthropologist for a restaurant that was opening nearby. He helped me settle on the first community I visited, Kaccllaracay, and we spoke about many of the ideas from the project. Francesco became officially involved in 2019, after I had spent many months living with and photographing the Andes, when I started to question how we could use these portraits to create a dialogue between Andinos.

Using the portraits I had taken during my travels, Francesco devised the methodology to interview neighbors from nearby communities about who they thought the people photographed were, where they thought they lived, and what they thought they did for work, among other questions. By doing so, we meant to break through the stereotypes often associated with Andinos and see how the people themselves see each other based on the perspectives of local people about other Andinos.

Through these captions, we are able to see how Cusqueños relate the traditional, to the rural, and the modern to the urban; progress and modernity are understood as the distance a person stands from the “dirt.” One can see this interplay in the interviews with local Andinos, as they note the dichotomy between themes such as: open shoes versus closed shoes, high altitude versus low altitude, uneducated versus educated, and agricultural versus nonagricultural. At the same time, symbols of modernity stand out to people, such as a laptop representing a good education, a paid job, and a home in the city. These interviews show the complexity of defining modernity in simple terms, as well as the social logic at play in local Andean perspectives.

What feeling or understanding do you aim to convey to readers of this book?

One of the main purposes of this project, even before the possibility of a publication existed, was to help demystify Peruvian culture. Many of us who are not familiar with the realities surrounding the Andean society of Cusco view them through a problematic dichotomy. On the one hand, “The Perfect Postcard” shows the Andes as a magical, lost-in-time place, and the Andinos as pure and almost magical people who are a static version of old folkloric tales. On the other hand, in “The Image of the Poor,” we can observe an insensitive and antiquated postcolonial narrative elaborated by the people of the capital to project a sense of superiority over those who did not inhabit the economic center of the country. With the publication of this book I hope to bring awareness to the realities of the Andean Society of Cusco and to compel the reader to get to know the campesinos, so often looked at through Western perspective as “others.”

How does your photography convey both tradition and modernity, do you feel they are at odds in your work and Peruvian culture?

One of the most fascinating aspects of Andean culture, which I learned during my time living in the rural communities of Cusco, is their ability to assimilate new cultures or ways of thinking into their own. This is mostly visible nowadays through the way Andinos practice religion, the syncretism they have achieved between their traditional beliefs on the earth, mountains, and the sun with the Catholic teachings of Spanish conquistadors blend in a truly remarkable way. From small details, like the Virgin Mary always wearing a triangular robe in the shape of a mountain, to bigger feats like the “Virgen del Carmen” Festival of Paucartambo, where you’ll find masked characters dancing around the town for days on end revering both Christian and pagan beliefs alike.

Just like with their religious beliefs, Andinos are seen conveying both modernity and tradition through their clothing, their poses, and their appearance, as a whole on the photographs taken for this project. For example, Lucia, who you see in a beautiful hand sown “pollera”––a traditional Andean skirt––is also wearing what appears to be a pair of Converse sneakers or Eulogio, who is wearing “ojotas,”––traditional Andean sandals––formal pants and a dress shirt is wearing a North Face jacket to keep from the cold instead of a traditional “poncho”. These photographs are meant to fill the gap between what we define as modern or traditional by encouraging individualism to portray the complexity of being a contemporary Cusqueño.

Are there any photographs that have a unique story/significance to you that you'd like to highlight?

Most of the photographs in this publication have a unique story and significance to me. As I thought about how to approach this project back in 2017, I came to the realization that the only way to truly understand Andean culture would be to completely immerse myself in it. To do so, I moved to 5 different rural communities in the Andres, where I lived for about three weeks each. For the first couple of weeks in each community, I wouldn’t take my camera out of its bag at all, the only purpose during those days was to build relationships with the individuals who lived in these communities. From cutting down trees and making firewood to help us keep warm with Luis in Cuyo Grande, to going every Sunday to church and singing “Apu Yaya Jesucristo” to the top of my lungs with Saturnina and her family in Choquecancha, or celebrating Corina’s 5th birthday with Evelyn, Alain, Andrea and the rest of the family in Choquepata, and even drinking Chicha de Jora––a traditional alcoholic drink from the Andes made from fermented corn––with Hipolito and Gabina until sunrise, as we shared stories from our childhoods overlooking the Sacred Valley in San Isidro de Chicon, these experiences are what this book is made of. I have always been someone who loves photographing the people he loves, from family trips to casual meetings with friends, my photography shines the most when there is a relationship behind the camera and in front of it. There is a warmth, a sense of love, and respect in these photographs that were naturally born from the relationships I built with every Andino featured in this project.