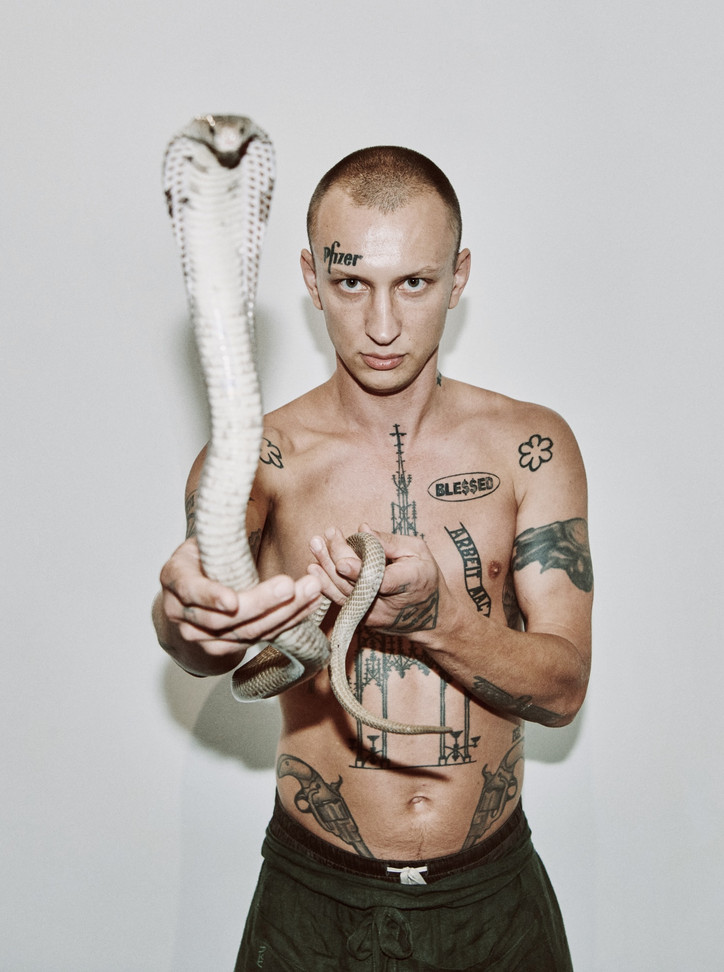

MCMLXXXV and Ron Athey

MCMLXXXV— Do you remember meeting on Instagram?

RON ATHEY— Yeah.

M — You DM’d me after I tagged you in some stories. It was the first time I came to L.A. I was at Akbar with Violet Chachki and Latex Lucifer, and our friend Mark Saldana was wearing this t-shirt with a quote from the British press saying: “Scots churchman slams sick HIV show. Bloody disgrace. Ex-Junkie who stabs himself with needles.” I had to post a picture, but I thought you were dead. I actually believed your pieces where you staged your own death.

When I found out you were alive and that it was actually you who messaged me and not just, like, the Ron Athey estate, I was so honored. So then I was like, okay, I'm coming back to LA. I have to meet him!

Can you describe that faked-death series a bit?

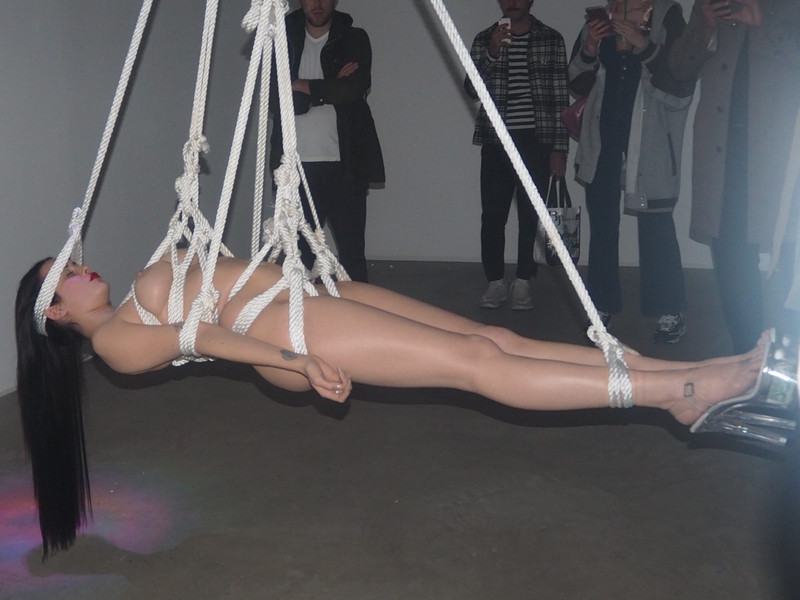

RA — In my performance work since 1990, I would display myself as dead—really, as a sexualized corpse, lying in state. I have an obsession with the miracle of incorruptible flesh and a metaphor for the living dead. Even the new work, “WILLENDORF, act two” is a riff on bejeweled catacomb saints.

M — Where will you perform it?

RA — I'll be bringing it to London soon. It’s based on a piece I made for Lee Bowery when he died called “The Trojan Whore.” Now I've brought it back as an even bigger lady in the BBL era. It's a fertility goddess for non-reproductive futurity, leaning into that Lee Edelman book, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, and thinking about why we got into such a big-ass-and-non-baby era. And the second part is inspired by Hyacinth, the catacomb saint, where I have people put jewelry on me, laid-in-state in a bed of viscera.

M — You gave me a relic with your HIV+ blood on it. What does that artifact mean nowadays when we have medications?

RA — Before it was literally a remnant of a living virus, and now it's of undetectable blood. Just like water from the Castalian Spring at the Oracle of Delphi still has a trace amount of psychedelics in it, my blood still has some remnants from 1986, when I was diagnosed.

How many years is that? Too many. Almost 40. Oh my God.

M — You must have had some crazy mutations in your body.

RA — Well, if there's anything to the theory of a weak strain, I think I must have had one. I was never sick sick. I just had complications. I had my spleen removed in like, 1990, because I was eating my platelets up and became a hemophiliac. But I never had low T-cells or pneumonia or anything like that.

But how old are you, and how long have you been positive?

M — I'm 34 and I have been positive for seven or eight years. I felt sick immediately, but I went to the doctor 76 hours later instead of 72. It was just too late for “the pill after”. I still didn't speak so much about being positive until the pandemic, which was when I started to research the history of the AIDS pandemic more and make paintings.

RA — I need to know more about you and your expression, through our generations’ gap! I only know that you DJ and make graphics with an HIV polemic. Morbidity, ostracization, endless big pharma (including Prep and Doxy Pep): how does your experience of HIV steer your work?

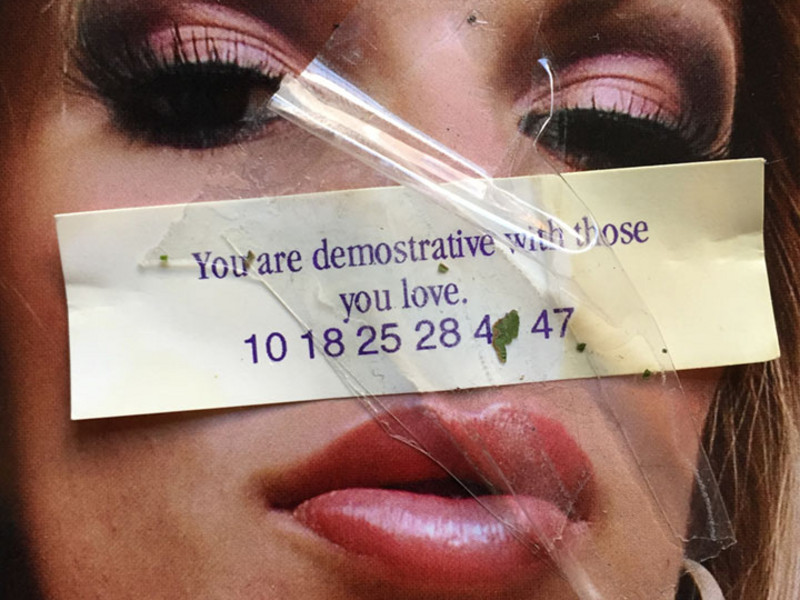

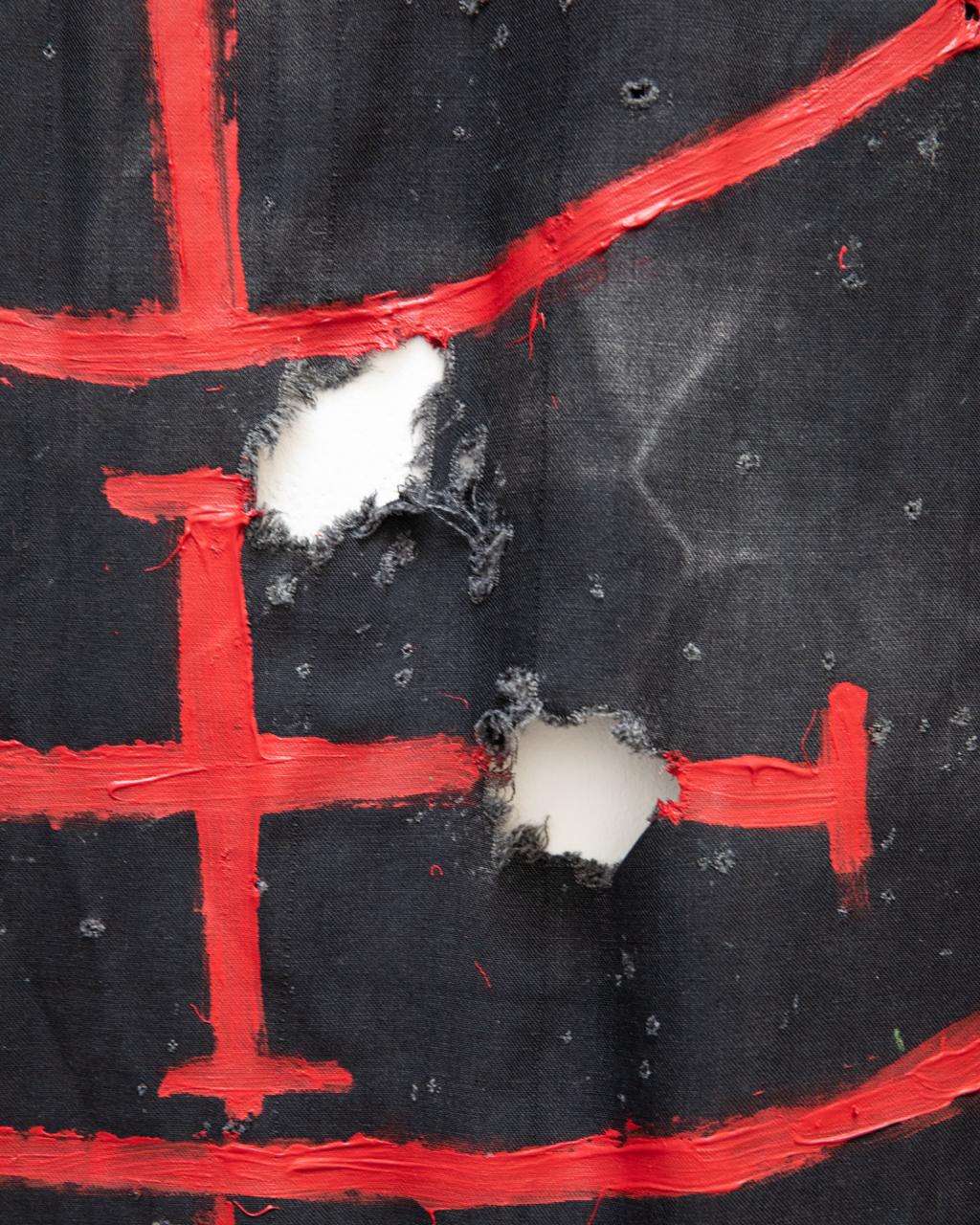

M — I was spiraling at home during the pandemic, which is how my HIV-spiral painting came into being: a visual representation of the mental process I was going through in that moment. And I had always made clothes. I always wanted to wear the yellow Star of David around my arm or have it sewn onto my clothes. My grandmother was in the Jewish resistance and ended up in Auschwitz, and I always took so much pride in her story and being a Jew in Europe after they tried to exterminate us.

So my idea was to do the same with HIV by making these spirals and writing “HIV-plus” on clothes. And then I started to color in the spirals, and I was like, wow, it actually looks like a church window. So I got more and more into church references. I put two things together that seemed separate and they became one. I realized I could do the same with visuals that I did as a DJ.

And then at some point, my ex-partner was wearing one of my HIV-plus jackets, and I found this crucifix and I put it on the plus-sign, and I was like, Oh my God, this is it. This is the Church of Positivity. This is Jesus on the Plus. It was the perfect symbol, the perfect logo. I started to appropriate more of these symbols from the church, and all of a sudden you have HIV everywhere, all over the church. It was so interesting to me, because in my research, I read how the religious establishment blamed the gays for spreading AIDS. “This is God's punishment for you,” but that is actually totally bullshit. The pharmaceutical companies played a much larger role.

So all of that culminated in a project called the Church of Positivity. Put Jesus on everything; show the hypocrisy of the world that we live in; refuse to shut the fuck up; be vocal; give people hope to feel better about themselves. That's what the Church of Positivity is about. I come from an extremely Catholic country, which I always hated. This is a new church, with the cross replaced by a plus.

I know you came from a very religious upbringing. How did that inform your stance on religion in your work?

RA — Well, I would like to say I look at it a different way. I went through all this religious stuff—and I did have a period of hating it—but then I actually started to call it ‘gifts of the spirit’. Even if I remove Christ from the equation, I still have these ecstatic gifts that you can't take away from me. I still have these archetypes of saints: tales of strength and martyrdom, which I found plugged into AIDS deaths really easily. So rather than being a rebellion at that point, it became survival skills, I think. And I still see through these ridiculously visionary metaphors.

M — My take always was a little bit of revenge: a revenge on the church by using their exact symbols, but making it something associated with positive faggots, which for a conservative Catholic person, I'm sure is one of the worst things they can imagine. It’s why I do the same things with symbols of nationalism. For example, look at what Germany is doing now.

RA — You're talking about the squash on Palestine protests?

M — Exactly. Again, it feels like nothing has changed, which is why I'm using old German, nationalist symbols, which often look like a plus. And this is also my personal revenge on what the Germans did to my family. I take their symbolism, and I turn it into what they hate the most. If a nationalist looks at my work and sees symbols that they used to think were cool—but then they represent only positiveness in the sense that I mean it—I find pleasure in that. And the best thing would be if one of them gets a heart attack.

RA — It is an interesting moment with symbology. I would like to tell you a story though, where it's not the outside threat, but the inside one. It was a gay journalist named Randy Shilts who had all the bathhouses and sex clubs closed in New York and San Francisco. So I think some of the “fuck you” in my work has been against the inside-censoring of the eighties, when gay culture was polarizing “good girls” versus “nasty girls.” That our internal punishment for AIDS was going to be that we either have to be sexless or monogamous and adopt or have a surrogate.To join reproductive futurity and be good people. You had people like Larry Kramer just screaming his head off that no one would grow up and blah, blah, blah.

But whether our future is the death drive or healing and starting families—that is still an individual choice. I don't need another gay person telling me what I have to do because I have AIDS.

Before PreP and protease inhibitors, AIDS was this nightmare that killed everybody interesting, basically. So then everyone not-interesting stepped forward and had a bigger voice, distorting gay culture by saying people just wanted to have children and marriage. That was the more conservative agenda, but I didn't think that's what everyone was fighting for and what half the people died for. So sometimes it is hard for me to understand what era we're in now with PreP and doxy Pep, and I guess there's just too many fragments.

Even with tender queers taking over the queer movement…

M — …Tender queers?

RA — The ones who are butt-hurt over anything. They try to shut you down. It's the same people who used to say, “Oh, there's a child two doors down. We can't be naked in here.” The specter of the child, the specter of the tender: it’s a passive aggressive way to make everybody dull down.

M — Sounds very suburban America. I imagine you have to deal with that a lot in Los Angeles?

RA — We have a certain suburban chic that is dialed in. If you play it right, it's a good time. There's nothing like a big house with a pool and toys.

M — How does L.A. define your identity and your work?

RA — I am an L.A. person above anything else. I’m from there and lived there my whole life except for six years in London. In the late ’70s through late ’80s, the climate in L.A. was both an incredible music scene and the epicenter of the porn industry. Public sex and dozens of leather bars, saunas, and gay sex clubs were the legacy of the ’60s and ’70s. I think this sexual L.A. gave me the post-porn element to punk, death rock, goth.

In 1981, I started making my first performances in this climate. “Premature Ejaculation” was my music project with Rozz Williams, my first boyfriend, of Christian Death fame. This was not a queer scene so we had to be strong, and it was effortless! I was inspired by the artist Johanna Went and the movie Deep Inside Annie Sprinkle (and her publication LOVE magazine that featured the first photos I saw of Fakir Musafar, as well as a urine fountain design from Günter Brus). I think the tacky shadow of Hollywood on everything in LA forced the underground to be more extreme—an anti-mainstream impulse.

M — People like you are very inspiring for me for that reason, because provocation is such an important aspect of art. I recently moved back to Vienna, and I feel similarly about my hometown. I realized it was always my hatred for that heavy, conservative Austrian society that inspired me to provoke. The more I find out about Günter Brus, the other Viennese Actionists of the sixties, and the Austrian avant-garde of the turn of the century, I see how all their art was always fueled by hatred of the extremely suffocating society and people around them.

RA — The more shit that's going on, there's more to press against. I mean, the Actionists were the most extreme out of nowhere. They were just filming themselves taking a shit. It was horny. It was pornographic in a grotesque way. And I think Brus is more of the aesthetic: cutting himself in half, drawing a line, bifurcating himself emotionally, maybe. I was always more with Hermann Nitsch.

M — Exactly.

RA — A bloody ritual over and over and over again .

M — He was iconic.

RA — But some women influenced me more, like Carolee Schneeman, Linda Montano, Valie Export. Her piece Action Pants, Genital Panic is outrageous— to be with your crotch out in a cinema.

M — I need to check that one out.

RA — She gets lumped with the Actionists but isn't. She’s more of an independent feminist.

M — Oh, right. Because that's also how I knew her. She's always mentioned in that context. Similarly, you’ve said in an interview that you’ve been characterized as an AIDS artist, which meant that your medium was AIDS, and that you didn’t agree. But to be honest, I find it really funny. I would definitely say about myself that my medium is HIV.

RA — Well, let's say it was considered a stigma at one point, so some people concealed it and I didn't because that is my polemic. I don't have a political statement except to bear witness and to be truthful and honest that I'm here being myself and pay the price for it. To still live your life, I think, and find joy and pleasure in the middle of all the rottenness: we can't lose that. That's a strong politic to me.

So I did maybe pay the price for the AIDS artist, but I never made work specifically about AIDS, maybe philosophical questions about AIDS and other parts of life.

Things are always described by sensation. Yeah, I'm a bloody disgrace. That's my headline.

M — I love that.

RA — I'm not going to get a trophy for being respectable, so I'll be the bloody disgrace and do that.

M — I think that's the biggest honor. The more we can annoy certain people, the more of a reward, in my opinion.

RA — I do think if you have something to press against, the work gets more interesting. And why there's trouble in utopia. There's nothing to press against.

M — Yeah, exactly. I feel like I need those Austrians to get me angry here and there so that I keep on getting inspired.

RA — I mean, I don't want to be miserable to make art, but a lot of people do their best work in the tension. In the tension of the moment, the art makes itself, I think.

M — Sometimes there has to be friction. I mean, there is no light without darkness, but you have to wear the right glasses to be able to see in both lights or log the absence of light.