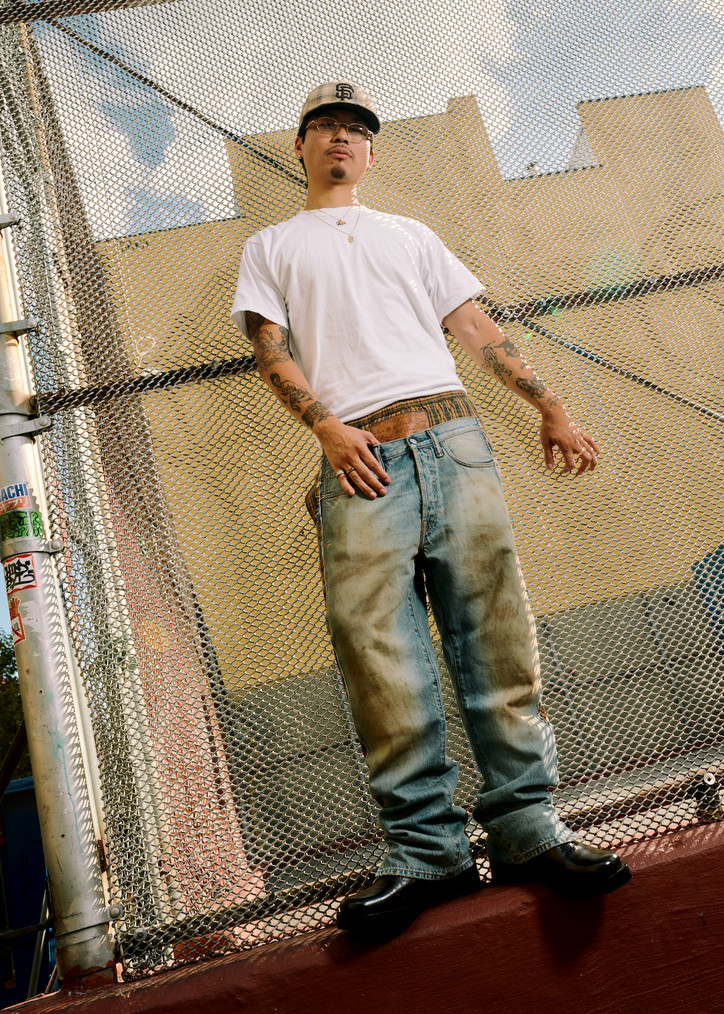

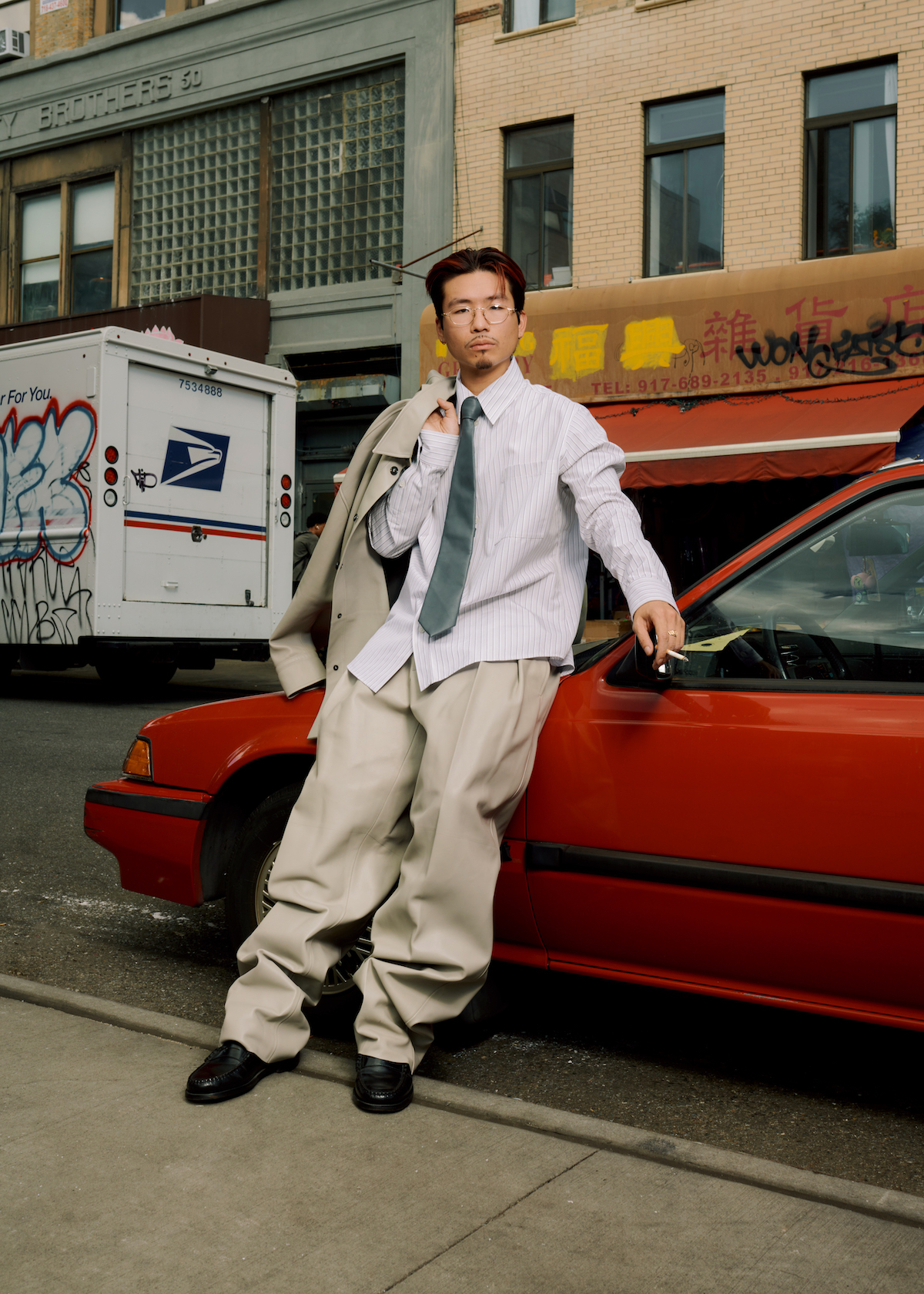

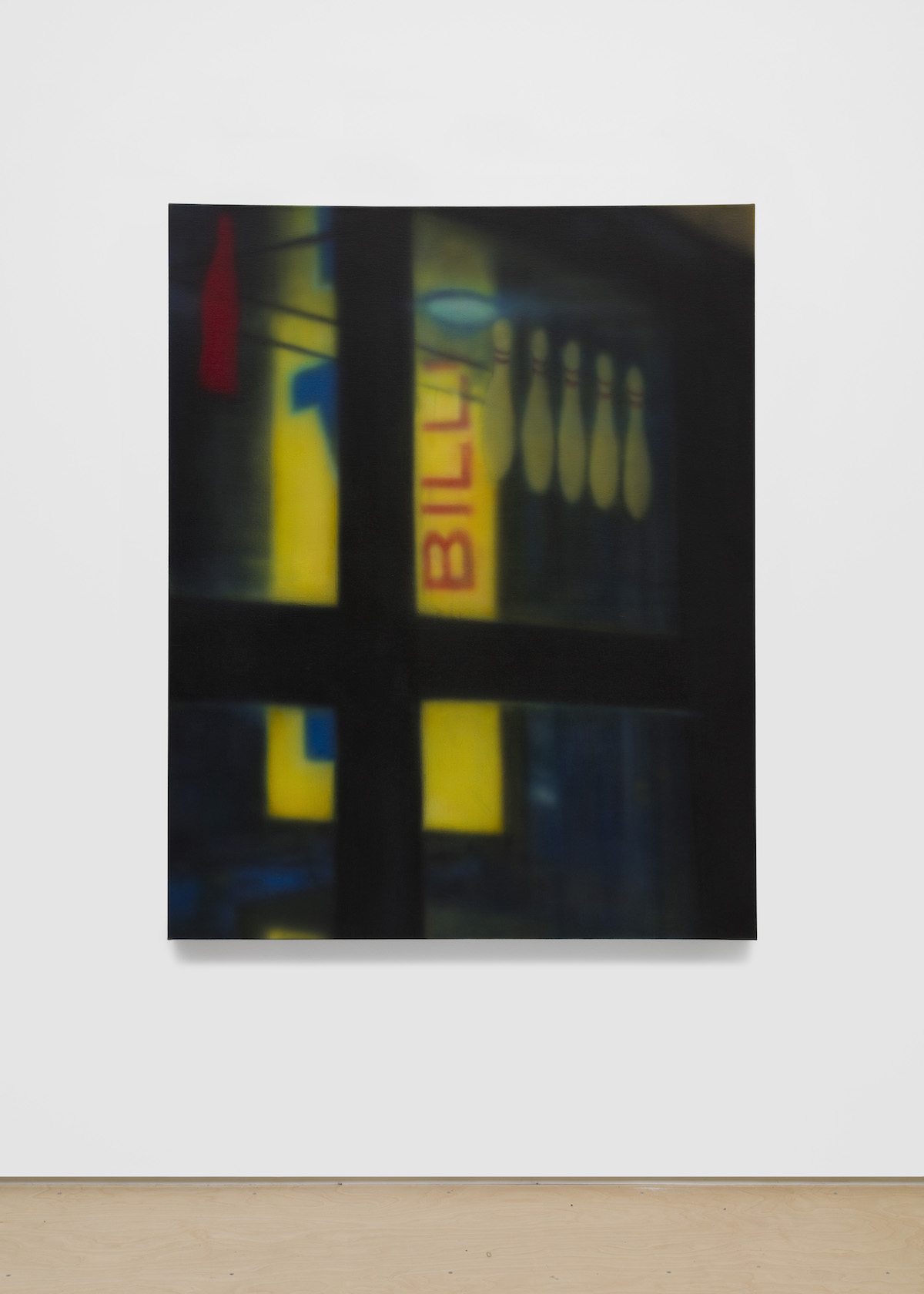

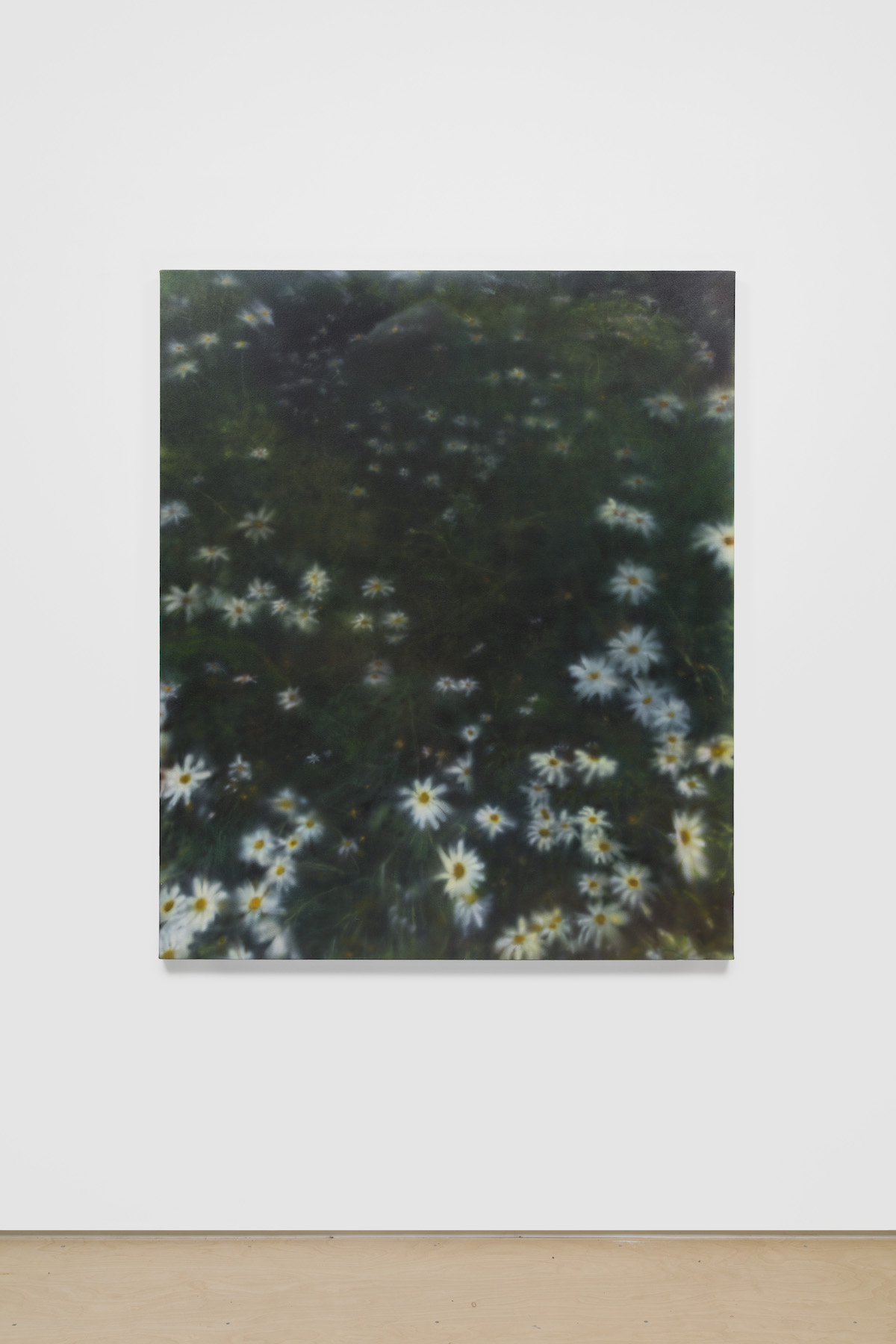

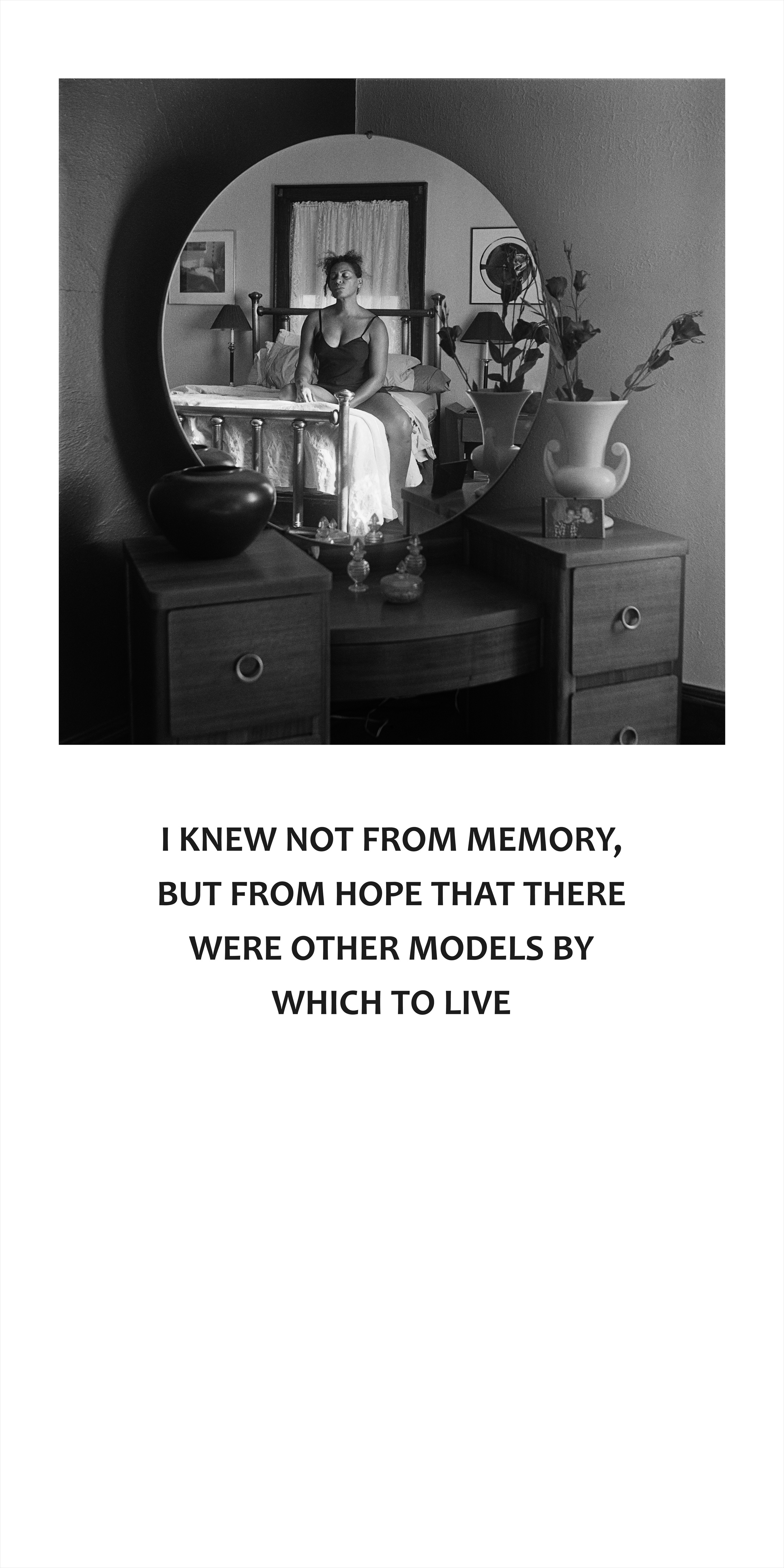

Through photographic portraits, landscapes, and scenes of domesticity, the exhibition features visual interpretations of rest by artists Tyler Mitchell, Allison Janae Hamilton, Daveed Baptiste, Gordon Parks, Carrie Mae Weems, Colette Veasey-Cullors, Cornelius Tulloch, Chester Higgins, Lola Flash, Kennedi Carter, Jeffrey Henson Scales, and Adama Delphine Fawundu, among others.

After the opening, office spoke to two of the curators of Rest Is Power, Dr. Deborah Willis and Dr. Joan Morgan.

Samuel Getachew— I was fortunate enough to see the exhibition on opening night, and first and foremost, I want to say congratulations. It was so moving, and so beautifully curated. I’m heartbroken that I couldn't make it to the artist’s roundtable on the 12th, but I’d love to hear how it went — any highlights you can share?

Joan Morgan— Well, it was really well attended — it was standing room only, which I guess isn't that surprising given who was on the panel. In addition to seeing these amazing artists present on their process and their craft, and give their thoughts and reflections on rest, I think the highlight for me was to have Tricia Hersey actually be able to see how her work is being taken up in the world, and actually have that engagement in real time. Often I think when you create things you hope but you don't necessarily know how it is not just being received but actually being engaged.

The most moving parts were the questions from the audience, about their own breakthroughs regarding issues of race and gender and giving themselves permission to rest. People shared how the art in the exhibition and Tricia's book and some of the artist statements felt like they were giving them permission to heal and to rest and to set boundaries, which of course is our overall goal and ambition with this project.

Deborah Willis— There were actually two doctors in the room that we didn’t know would be there. I was so impressed with them sharing their moments of what the exhibit meant to them. As doctors, people don't see that they need rest too. When a patient comes in, they have to get up and go back to work, if a patient dies, they just have to get up and go back to work.

Some of the questions also talked about the grind culture that we experience as these artists, that we need to keep moving, we need to keep working. In Europe, there's support for the arts, but in the US rarely do our artists have grants or government support from their country. That was another aspect we hadn’t thought about.

I know Tricia’s work was very foundational for the concept behind the exhibition. Can you tell me more about how the idea for the exhibition came about?

JM— Every year thematically, we come up with a topic that we’re going to explore at the Center for Black Visual Culture. Our first one was Black joy as resistance, and our second one was redefining home, but we felt like we actually needed a 3-5 year commitment, and we wanted to come to work collaboratively outside of the walls of NYU.

The exhibition is the launch of our larger initiative, the Black Rest Project, which came about quite honestly because Deb and I had just come out of two years of virtual programming during COVID where we were often running two programs a week virtually. For a time when we were all supposed to be locked down and standing still, we emerged from it pretty exhausted. I noticed that was basically everyone's response: really exhausted and depleted, and even more so for people of color.

DW— We as an academic body needed to focus on rest. Joan, Kira [Joy Williams] and I decided to put together an advisory committee and to invite scholars who we knew were going through the same questioning, ask the questions, “What do we think about it? How do we talk about it?”

JM— The exhibition is our first attempt to amplify visual narratives of Black rest.

Do you see the Black Rest Project exploring non-visual mediums in the future?

JM— Oh, absolutely. That's why we brought in collaborating partners, and we're about to meet with the advisory council again. We're working with various factions — historians, scholars, activists — many of whom don't necessarily work in visual culture but have real ideas about how to bring rest back to their community.

The exhibition features a really diverse range of artists, some much more established like Gordon Parks and Carrie Mae Weems and some who are quite young, like Daveed Baptiste. How did you make those curatorial decisions?

JM— We learned a lot about what we each thought about rest in going through the images. We had some really robust debates about what was restful, because we became very aware that what looks like rest to one person may absolutely not look like rest to another. It expanded our ideas.

With the photo of a barbershop, I was like, “Why is an empty barbershop restful?” The barbershop looked like a place of labor to me. But then Deb explained how much goes on in Black hair care spaces, and also how that moment when there are no customers and you're closing down for the night is the moment right before rest. I learned a lot because I wouldn't have necessarily picked that image, but Deb went right there also because of her experience growing up as the child of a mother who owned a beauty salon. We had to really expand our notion of rest beyond just, like, Black bodies sleeping.

DW— We decided to invite people to send work, as well as look at some of the people that we know and go through their archives. The range started with younger artists that I met in different cities. I travel a lot, speak to a lot of photographers, and they send me portfolios and ask me to review their work. I didn't ever think that I'd be working with them on some projects, but I thought, “oh, this is a good person to keep in mind.”

There’s some images that reevaluate rest from my own memory, from the collective memory of the three of us. There was also the worthiness that I felt of the photographers who took the time to make images, like the Gordon Parks image of a woman looking out the window in Harlem with her dog. I felt that it was necessary for us to explore.