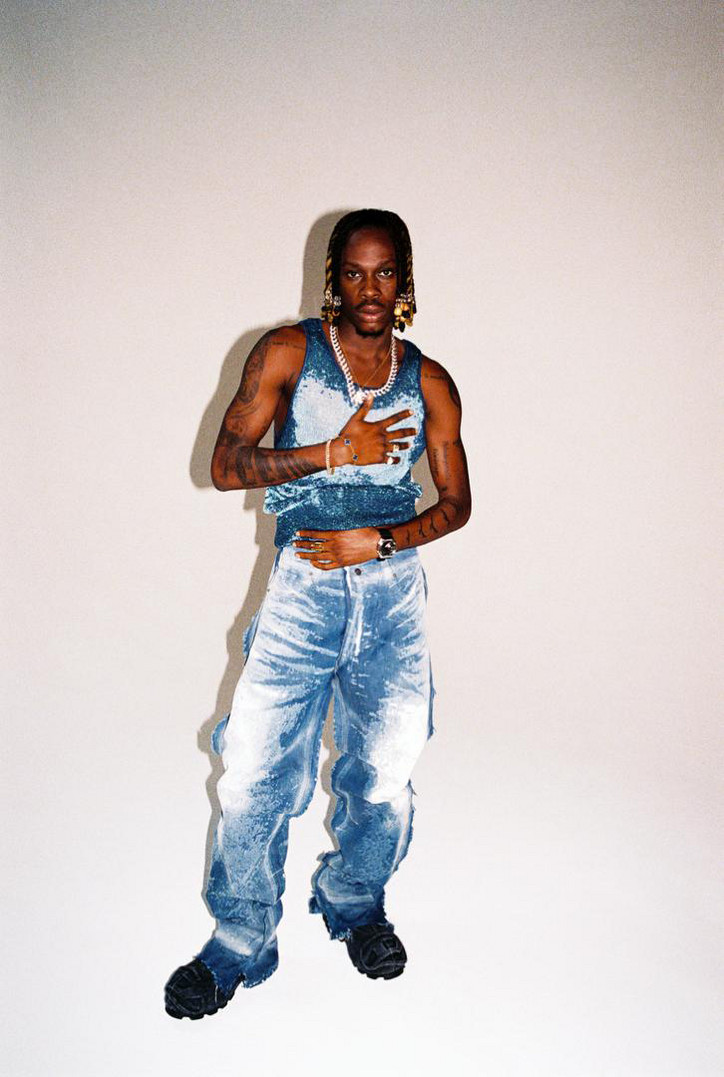

FIREBOY DML wears JACKET and PANTS by LOEWE, SHIRT by PALM ANGELS, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN

Stay informed on our latest news!

Stay informed on our latest news!

FIREBOY DML wears JACKET and PANTS by LOEWE, SHIRT by PALM ANGELS, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN

The shift he notes in his worldview over the last few years was also the catalyst for the album — a catalyst Fireboy says he requires in order to begin a new project. “The truth is, I work better when I have a story to tell and a vision to pursue," he says. “It's easier. I don't just get in the booth and randomly say, ‘oh, I want to make an album.’ Something has to happen, a life changing experience or a switch, and that's what really happened towards the end of last year.”

“I learned a lot about what’s really important,” he continues. “I lost friends: I lost a friend to death, I lost a friend to life. So right now I'm all about going back to the basics, back to the roots, focusing on my family and the things that really matter to me, because if those things are not in good condition, then your success doesn't really matter. It's nice, but there's always more, there's always going to be more. But if I really focus on the things that matter, all these things would just be a huge bonus. It’s so easy to lose sight of that.”

Throughout our conversation, he controls his voice with the gentle, almost gingerly cadence of someone who has learned through experience how a single spontaneous choice of words or melody can transform a life in an instant — for the worse, or in Fireboy’s case, for the astronomically better. His 2021 global smash hit “Peru” emerged during an extended freestyle at a studio in San Francisco; birthed in the spur of the moment, the song’s earworm chorus led to the accumulation of over 500 million streams and the introduction of Fireboy to an international stage. Since then, he has collaborated with stars including Madonna, 21 Savage, and Ed Sheeran, released his third album “Playboy,” and just weeks before our conversation, performed with Jon Batiste at Coachella.

FIREBOY DML wears SUIT and SHOES by LOUIS VUITTON MEN'S, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN (left)

FIREBOY DML wears FULL LOOK by DIESEL, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENTS OWN (right)

Global superstardom was not necessarily predictable for a young Fireboy, who describes himself as a “very quiet, nerdy kid growing up.” Born Adedamola Adefolahan (the “DML” in his stage name is an abbreviation of “Damola”) and raised in what he describes as a “sheltered” environment, he cultivated his creativity during the long hours he spent alone and indoors, reading books and listening to albums. “From there, I realized I could write, I realized I could come up with words,” he recalls. “Mostly poems at the time. I used to write short, mostly sad poems.” He was able to truly cultivate his voice when he left home to study at Obafemi Awolowo University five hours away, suddenly thrust into the mantle of adulthood and independence for the first time in his life.

“That's when I really started to discover myself,” Fireboy recalls. “I thought I was going to be a scholar because I was a straight A student, I was always so serious, so good at my books. But the university is very diverse, and I started meeting creatives, dancers, writers, poets, different people. I was inspired immediately. And before I knew it, I started going out with the cool kids in school, the dancers, the musicians, and going to the studios with them. As a joke, one night I got in the booth, and I just made my first song. And it didn't sound bad at all.” That night, he found himself replaying the makeshift demo over and over again in his dorm room. “Before I knew it, [my poems] started developing into rap, but unfortunately, I don't have the voice for it,” he continues. “I'm a singing ass nigga — I tried to rap a few times but… it didn't work out. So I tried singing and I realized I was really, really good at it. I was like, okay, so this is it.”

FIREBOY DML wears JACKET and PANTS by LOEWE, SHIRT by PALM ANGELS, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN (left)

FIREBOY DML wears FULL LOOK by DSQUARED2, GLASSES by TIFFANY CO., GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, HAT by NEW ERA and JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN (right)

Fireboy speaks about his career with a tightrope-act balance of matter-of-factness and humility. He is under no illusions about his role in the global surge of popularity experienced by the Afrobeats genre since the late 2010s, but he is also refreshingly uninterested in battling to keep the spotlight on himself. He is sparing when discussing the details of his own success for any longer than necessary, but he becomes animated when he speaks about the influx of young and fresh new artists emerging from the continent. “There’s a lot of talent out here. Right now the doors are so wide open for everyone to come in and flourish,” he describes. “As a true artist and true creative, it's exciting for me when a new crop of talent comes and it changes the soundscape of a generation. It's a beautiful thing to see. [The soundscape] gets tiring sometimes, it needs to be reshuffled once in a while.”

FIREBOY DML wears FULL LOOK by DIESEL, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, JEWELRY is TALENTS OWN

When I ask if he has any advice for that newer crop of artists, Fireboy becomes reluctant. “I'm not a fan of giving advice because I feel like life is crazy, and no one really knows it all. But I would always say, find your sound. Finding your sound is the beginning of everything. It doesn't start with going out to look for favors or for [someone] to help you. Whoever's gonna help you, they have to see something in you first, and if you don't put in work, there's nothing for them to see. The secret is always being there when the game needs you to show up. That’s how you succeed. Always keep showing up, at 3AM, at 6AM, when the game needs you to just stand up and record and make music.” He pauses for a moment.

“The game is a very jealous bitch — sorry for swearing, but for lack of a better word, music is very jealous,” Fireboy continues after a deep breath. “I had to sacrifice a lot of dreams to become who I am today. That's one thing that's always been constant: music is selfish. You have to give in, you have to be ready to sacrifice almost everything to have it. As long as you do that, everything else will fall in place — the money, the fame, the investors, the backing, the support, the fans — everything else will fall in place. Find your sound.”

FIREBOY DML wears JACKET and PANTS by PDF, GM2100-1A WATCH by G-SHOCK, HAT by NEW ERA and JEWELRY is TALENT’S OWN

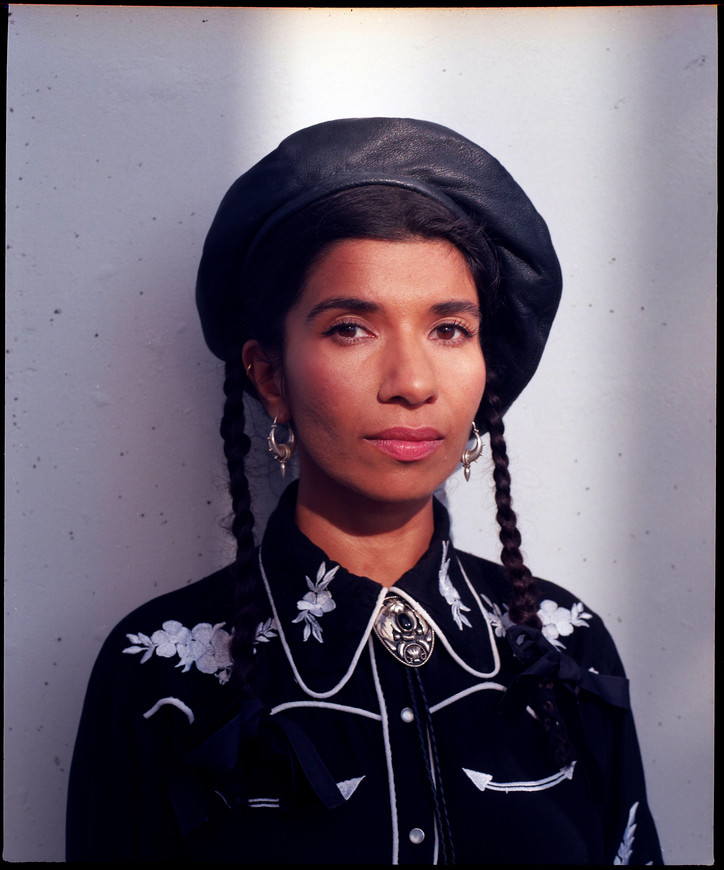

You just played your first show in Melbourne which also happened to be your biggest ever show outside of London. How does it feel?

It was amazing! I can’t explain the feeling; I need to think about the feeling more because I’ve been feeling this a lot at all the gigs I’ve played around the world. This is my first live tour in Australia, and I’ve been so excited about it. Playing my second biggest headliner show in a new city on the other side of the world, makes me feel so happy and appreciative of the people because they’ve all made an effort to come out to the show, to support the record, and to support me as an artist. That is what allows me to do what I’m doing, so I owe everything to them, the fans. I was so nervous before the show, there were so many people.

Was that the most nervous you’ve been before one of the shows you’ve done on the tour?

I think so, yeah. It is the ones where I have no expectations or I don’t know what it is going to be like, and then the crowd ends up being massive. Also, this was the first time I played on a stage that was in the middle of a venue with the audience all around. I wish I could’ve moved around a bit more because I felt bad for the people who were just looking at my back.

Yeah, the stage is so strange at that venue. How much of an impact do you think growing up in London had on your music?

Everything, really. I am really happy that I am from London, and I grew up in the middle of the city. There is inspiration everywhere and so many opportunities too. I was going to gigs from the age of thirteen onwards. In a city like that, there is something happening every weekend; all the bands will come there. Everything is at your fingertips; in terms of musical conditioning and education, it made a huge difference. I feel like a creative everything you put out is everything that is inside, so London is a huge part of my work. It’s funny because with this latest album, DREAMER, I made most of it outside of London in the countryside, because I needed that space to focus and get it done. I owe everything to London; it is one of the most amazing places in the world.

How was it working in the countryside? Did you feel like you had different inspiration to working in the city?

Yeah, the inspiration was very different because you’re surrounded by nature. The first two times I went up to this really remote place in Scotland called Cove Park, where they do artist residencies, and it is a two hour walk to the nearest shop. In the same way that people from rural areas freak out when they come to a big city, for me it’s the other way around. That's how I feel going to the countryside. It can be quite scary because I’m not used to being in such an isolated place. It was a very different experience for me, but the nature was so beautiful, and I would start every day going for a big walk. I was very disciplined too because I knew I had to make the most of that time. I would wake up, go for a walk and then work the whole day because there is nothing else to do.

How was it being alone doing that; did you feel quite isolated?

It kept me focused really, because in London my studio is in a big building with a lot of friends and there is always something going on. It’s so easy to be distracted. You can’t make a song when you’ve only got an hour here, and an hour there, you need to cordon off a whole block of time. I was so busy with gigs, meetings and general London life so that’s why I decided to get out. I just turned my phone off and that was it.

How long were you there for?

It was different each time. The first time was three or four weeks, the second time was two months and then the third and fourth time were about the same one or two months at a time.

Wow, that is nice though. It paid off. You studied history and ethnomusicology, got a master's degree and then became a human rights lawyer. Just on that alone, it’s clear that your life is more than music, do you feel that having such a wide background and knowledge of so many different spheres has helped influence your music, in a way that might even be subconscious?

Yeah, so in my undergrad studies in history and ethnomusicology, I went to the School of Oriental and African Studies which is quite a specialist college in the University of London, it is where people go when they want to learn about things that aren’t Eurocentric. I didn’t originally go to study ethnomusicology but in the first week of uni the music department put on some performances and I saw a kora player and it was the first time I had ever seen that instrument and it just blew me away, I went to find the head of music and was like "Please let me do this course," and they let me on the ethnomusicology course. That was one of the most important things that has happened to me, for the first time I was exposed to so many different kinds of music from so many different cultures around the world and I was realising the importance of music. It is definitely the most spiritual art form in the West, but it has kind of been commodified into something that you listen to for entertainment's sake and it’s easy to not think beyond that. Then when you start looking at music in a historical and cultural context in different countries you realise that it is so much deeper, you start thinking about music in a different way.

Do you think that understanding of the relationship with music in cultures outside the West inspires what you want your music to mean and how you want people to connect to it?

Some of the deepest music experiences that I have had have been listening to music that is from a totally different culture, and I am the outsider. I am just there experiencing it and it just touched me so deeply, made me cry or made me feel the most intense emotions. That made me realise that you can feel that power and appreciate music from any different culture even if you aren’t necessarily part of it. In turn that led me to believe that there is a universal force contained in music in general and I feel like every single artist is on a quest to get to the essence of that, finding out the answer to what music is and does it mean. Some people are way further along that journey than others, that’s why you have people like Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix or Bob Dylan. These people whose music has transcended so many geographical, and historical boundaries and got in touch with so many people. For me as an artist, I am also on that journey to figure that out and so even just being here in Australia and playing those first few shows to full audiences and seeing how the music has moved them. Seeing people cry in the Melbourne audience was a very surreal experience. When you make your own music your relationship to that music is quite different to the music you listen to made by other artists. To see people responding to my music in the same way I respond to the music that I love listening to feels amazing. It reassures me that I am on the right path, doing what I am supposed to be doing.

With that, your music grabs influence and inspiration from so many different genres, eras, and cultures. Do you feel like today as so much music has been made it would be a missed opportunity if you didn’t embrace what you enjoy about different music to create something unique?

The most important thing for me is to create something that feels real, that is a true reflection of your creativity. So, it is not an imitation, where it is like going down the path, where I am trying to create this sound by using different elements of different things. I just don’t think about it in that way. I know when you hear my music you can hear the different influences of the things that I love. There is a strong element of certain types of guitar sounds that reflect how much I love 80s guitar band music, there is a dance element that is a reflection of electronic music that I love. For me, I am just creating that reflects a feeling and it just comes out like that. You are right it is hard to describe what the sound is. It is hard to answer that question when anyone asks me what music I make, I think it is better to just listen to it.

It’s interesting when you say you do what feels right, at the show you said you’ve only written one happy song. If you don’t listen to the lyrics the tracks are mostly uplifting and with complete ignorance, you’d think nothing more of them, but when you go into depth on what the songs are about a lot of them are extremely heartbreaking. I think ‘Sunflower’ is the perfect example of that. Where does it come from to have these emotional songs on backing tracks that are the complete opposite. Is that something you do on purpose or is it what just feels right?

I think with ‘Sunflower’, the subject of it is sad and I was feeling sad when I wrote the lyrics. There is a longing in it, but the actual track is a big euphoric, electronic, dance track. It is conveying two things, through the words it is conveying loss, legacy someone leaves behind, the rupture that might happen when one person suddenly disappears, and you are just left with their work. The feeling through the music is that even though you are going through a tough time and experience loss, there is still this elation that you have something to remember that person by whether it's someone you know or don’t. At the time I was reading a lot of poetry by Lord Byron and John Keats, they both died young, but their work is left there, and you can still have a snapshot into their minds a hundred years later and that is the beautiful thing. That is what I was trying to convey in the music.

It is written so well, the idea of meeting under the sunflower is so deep. It feels so open to interpretation.

The sunflower reference is a nod to William Blake. He has a poem called Ah! Sunflower, the whole poem is about living and dying.

Something that stands out to me about your songwriting is the influence for the songs. For example, you quoted Thomas Hardy and John Keats’ writing as the inspiration for songs. It’s really interesting, I know Kim Gordon uses lines from books as lyrics but there’s something that feels extra special about using a story or a piece of writing to interpret their story in your own way. Where did the idea to begin doing that come from?

I always keep a few poetry books in my studio, I think reading poems is a really good quick way of getting inspiration. Everyone who is an artist will know that there are times where you are in the studio and you’re trying to work but you feel like you are up against a brick wall and not being productive. When I am in those moments where I am not making music and feel stuck, I will take a break and read something. I find that really helps because it takes your mind off the frustration, and you are reading something that someone else created. It can often be inspiration for something else and that’s how it works really.

I have this big anthology of English poets through the ages, starting at Shakespeare and I will read a few pages and see where it goes. English is my first language so I turn to English literature. I always think what else am I missing in all the other languages and there are so many languages that are so much more poetic, and I wish I could tap into those as well.

Does that idea come from being so well-rounded in international music?

Yeah, I think so. Also, because I am Pakistani, I also can speak a little bit of Urdu. Urdu as a language is really poetic and I wish I could read poetry in it. Maybe I need to get lessons in it.

How important is it to incorporate your Pakistani heritage in your music?

In DREAMER this is the first time that I ever incorporated instruments from Pakistan in it. The album starts and ends with a harmonium which I bought in Pakistan. I had really wanted one for a long time, so I am glad I got that. I also play a sitar on Lilac Twilight. Up until that point I was quite stubborn about mixing the two sound worlds, because I felt like they were separate, but for some reason on this record it felt right. I feel like I incorporated those instruments in a way that fits with my sonic palette anyway. It’s a nod to my culture and ancestry; it just felt right and I’m really happy I did it.

You originally were going by the moniker ‘Throwing Shade’ you dropped that in favour of your real name, how important is that to go by your real name?

First of all, Throwing Shade was just a name that I picked for fun when I was DJing at parties with my friends while I was at uni. I never envisioned that I would be doing music full-time at that point. Then I got to a point where I was thinking about myself as an artist and the space I was occupying. I was getting more and more people from ethnic minorities who said they respected what I was doing and looked up to me for it. That is something I never had thought about before but then that got me thinking more about identity and presence and the fact that you don’t see a lot of brown faces making the music I made and you don’t see people with non-western names on big festival line ups or released on labels, because there are none. You think of Zayn Malik and that’s it. I thought, you know what I want to be straight up about my identity, and I want my name to be my name, I want people to read it and say it and for it to be normalised. Yeah, I am really happy.

It is so big for me too; I am Arabic, and in my spheres, there are no other Arabic people. My sister and I talk about it all the time, we are the only Arab art kids we know, she goes to fashion school and I’m a writer. It is so nice seeing people in creative industries from diverse cultural backgrounds. I’m sure it is similar in the UK where it feels like there is a stereotype that only lets you play a certain role in society. It is such a big deal having someone like you break that stereotype and be who you are in this position.

It is not easy; those stereotypes are there for a reason and people want to enforce them and it really frustrates me. I don’t know what it is like in Australia. But in the UK for example, most of the time when you see a South Asian person on TV it’ll be a comedy where they are making fun of themselves. There is nothing beyond that or it is a different kind of stereotype, where you are going to paint this person as a terrorist or corner shop owner. We need to break out of that, it is starting to happen now. I get a lot of positive comments not just because I’m brown but because I am female, and I have an Arabic name and people identify with that so much. We’ve just got to keep going.

Yeah, it is the same thing here with the media. The Lebanese-Australian stereotype is so far away from anything that I have ever related to, and it is crazy because I have never seen anyone like me ever portrayed in the media. That’s why I think what you are doing is so inspiring. You are breaking those stereotypes.

That’s why you also have to keep doing what you’re doing, because it’s important too.

You’re here now in Australia on your second world tour, you’ve just put out your second album, you’ve been making music for years, but you are at this point where it is where you are beginning to get this wide scale international traction. Do you know where you want to take this?

I mean, I don’t know. This is the crazy thing. It has just happened. It has been ten years since my first record came out. I have been doing it for a while now, but it feels like I am at some kind of tipping point now, suddenly people in all different cities are listening to the music and coming. I sold out Melbourne, but I also sold out my first shows in Paris, Amsterdam and New York, all these places I had never played before. Playing these shows is kind of the physical manifestation of what the music is doing, otherwise you don’t really know. Yeah, I see people streaming it but that physical space where you see people enjoying it, it is very special. No one knows what is going to happen next. I just want to keep going and put out more music. I love doing this. I just want to keep going and see what happens.

It’s funny, someone asked me about my guitar after the show. Then it made me think about that guitar. I bought it when I was sixteen, I had a summer job working as a delivery girl for a sandwich shop. I used to deliver sandwiches to a music shop and that guitar was in the window. I told myself I was going to save up all my money over the summer and buy the guitar at the end of the summer. That’s what I did, I even wrote the date I bought it on the back of it. Now I’m just like woah, imagine telling my sixteen-year-old self who was saving up for this guitar that I would tour the world with that same guitar. It’s mad.

How’d you get started making music?

A friend of mine showed me Ableton. It was a cracked version so I couldn’t save anything. If I wanted to start a new song, I had to close it, which meant deleting the music that I’d made. When I felt the track deserved to be recorded or saved properly, I would write what I was doing on a piece of paper, and then I would do it again, but it never really worked. Eventually, I got the normal version — which was also cracked, but that one worked.

How has the club scene changed since you first started going to club nights in Paris?

When I started going out as a teenager 15 years ago, there was a lot of bloghouse. Only a handful of the artists from that era made it mainstream and the others sort of vanished. The ones that became popular, I kind of drifted from sonically. People associate me with the club scene here, which I’ve accepted. But around that scene, there’s a lot of stuff I just don’t identify [with]. Club producers essentially have very similar career goals, and there’s naturally a lot of jealousy, frustration, and phoniness in that scene. In the scenes that I feel closer to personally, there’s less animosity, less competition. Everybody’s doing their own thing and truly supporting each other’s work.

What was it like transitioning from creating on your computer in a really private space to performing live?

I don’t feel [like there’s] any type of transition, to be honest. Especially when it comes to djing. With live performances, I feel more stress naturally as I’m performing my own productions, usually in more institution-type venues and events.

When you say “too popular,” do you mean in terms of the style of the sound or was it more about the community around it?

Like, Justice made an incredible debut LP. And there’s nothing wrong with the stuff they’ve put out since — it’s really impressive — but it feels less iconic and fresh as CROSS still is. It was targeted at a bigger audience. I’m not hating on the fact that it became popular, but it was sonically less interesting for me — or there was less shock when I heard it. I was genuinely curious about other genres at that point.

I think when an artist finds success, it’s easy to get stuck in that sound, which gives them a lot of pressure but often just a B-side feeling. But how do you build off what worked with your last releases without it becoming redundant?

I’ve always made music for myself. It’s obviously nice if people like it, but I’m far from a perfectionist. I have a lot of releases, a big catalog of stuff that’s not even finished, but it’s still online. I could just remove it, and I have sometimes because I feel like it’s trash, but then somebody DMs me and asks for it back because they were listening to it every day. And for that one person, it sucks to take it down.

It’s always hard to distinguish excitement from stress, I feel like they really go hand in hand. When I release something, it might be excitement, but I read it as stress. And so I feel the need to drop something new really fast — almost instantly — because my previous release doesn’t sit right with me. This is the first project that I’ve done where I’m still okay with it while listening to it so close to its release date.

Why do you think it is that you’re more comfortable with this one?

I think just simply going back to what I was listening to in my teenage years as well as new music inspired by that era has been fun. I just don’t take it that seriously.