What’s your favorite place in New York?

My favorite place in New York is probably my house. I'm a big homebody. But there's some other little gems in New York that I really love, like Holographic Studio. Street Fever at Punk Alley is one of the best places in New York to go — it's a junk shop and tattoo studio.

I always try to support the mom and pop shops. Never go to a 7-Eleven or a Starbucks or anything like that.

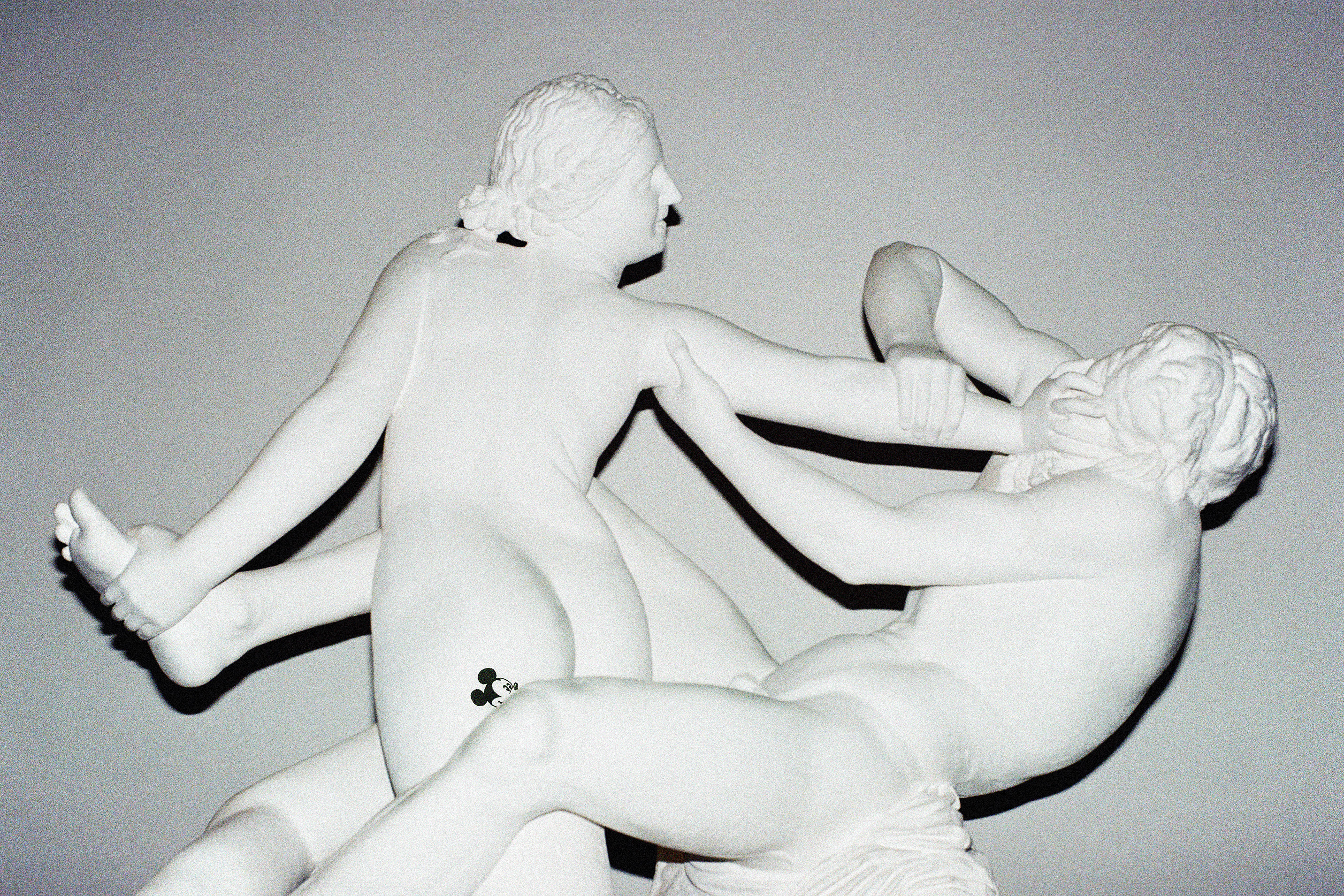

What is the most memorable tattoo you’ve ever given someone?

I think the most memorable tattoo I've done, or the one that has stuck with me the longest, is an upper back piece I did in the pictographic letters I'll do often. It says “energy” across my friend Cosmo’s back. I did it in Melbourne, Australia. We had one day to do it. I freehanded it, and we were there for about 12 or 13 hours. That feels like one of my favorite tattoos I've done.

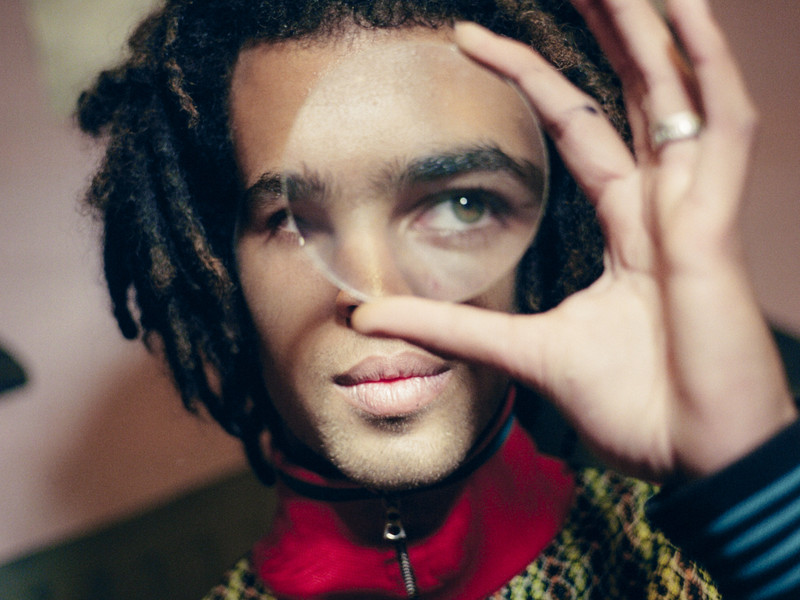

Do you always do customs?

Yeah, I've always done custom tattoos. I think there's something really nice and special about the collaborative nature of sitting together and talking out an idea. I really like feedback and input when I'm tattooing. I'll often have moments where I'll stop and ask a question.

The majority of my work ends up feeling collaborative — I guess my entire body of tattooing is somewhat collaborative with every person that comes in. The way I book appointments, I almost require a prompt — whether it's an idea or just a photograph, it's basically just a jumping-off point. I feel everyone out and just slowly come up with what we're doing.

Every tattoo I do is conceived, drawn, and done on the spot. There's a lot of spontaneity and it’s all based on intuition. I never draw things up beforehand.

Depending on the type of imagery or idea we're working with, I'll sometimes try to take a little time to sit and think about it, and how we want to approach it. But I really enjoy leaving it up to the actual day and moment of our appointment.

Sometimes the placement of a tattoo will dictate the image, and sometimes an image will dictate its placement. A lot of things I do freehand, but in other instances, I'll draw beforehand with the person there. Even when things are pre-drawn, I always need to leave a little bit of room for improvisation.