Alicia Hall Moran—Here’s what I love about the opera: complexity. Opera is layers upon layers. It’s all the instruments of the orchestra, and many voices, sometimes firing all at once. It’s many points of view inside one show. Opera is an argument, large forces of passion and idea pressing up against one another and a protagonist with a problem—the bigger the better. The biggest problem, the biggest thing, the most profound emotional states, these are all at home in opera. It is hard to find anything that is out of place in the opera.

[It] also challenges time and space in extreme ways that I find exciting. You know, sound travels so much slower than light. In the blink of an eye we can peek the truth, but in opera we have compositional permission to wind our way painfully— or pleasurably, as the drama dictates—in and out of the truth. Slowly. We are released from real time in a clear and distinctive way. It just takes a long time to sing a sentence.

Imani Uzuri—For my own work, I love the way that contemporary opera allows for abstraction and experimentation. This is important to me as I conjure the worlds within my large works. Even my first album, Her Holy Water: A Black Girl’s Rock Opera, was named as such to underscore that even the minutiae of our lives as Black folks are epic. Writers like Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Ntozake Shange, Toni Cade Bambara, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Octavia Butler, Sonia Sanchez and Lucille Clifton understand that our everyday lives as Black people are filled with magical realism. It is who we are as Black people—we dream prophetic dreams, we see the future, we understand the nonlinear nature of time, we understand that the veil between here and there, now and then, death and life is thin. Contemporary opera provides a canopy in which I can explore these interstitial spaces of the spirit, mind and psyche. It helps me think larger, ritualistically and circular.

KD— Why is opera important within a Black cultural context?

IU—I think our lives throughout the Black Diaspora is operatic grand, even in our supposedly ordinary day- to-day happenings. What seems simple is so majestic, from the various ways we walk, how we dance, pray, dress, think, cook, our use of language—poetic and otherwise—how we live life. In the context of art songs, I love that folks like Paul Robeson, Odetta, Richie Havens and Roberta Flack include African American spirituals and work songs as part of their repertoire. These haunting melodies and layered stories come from our enslaved Black American ancestors. They provided inspiration during the Civil Rights Movement and still provide wisdom and inspiration today. They are coded, rebellious and spiritually transformative.

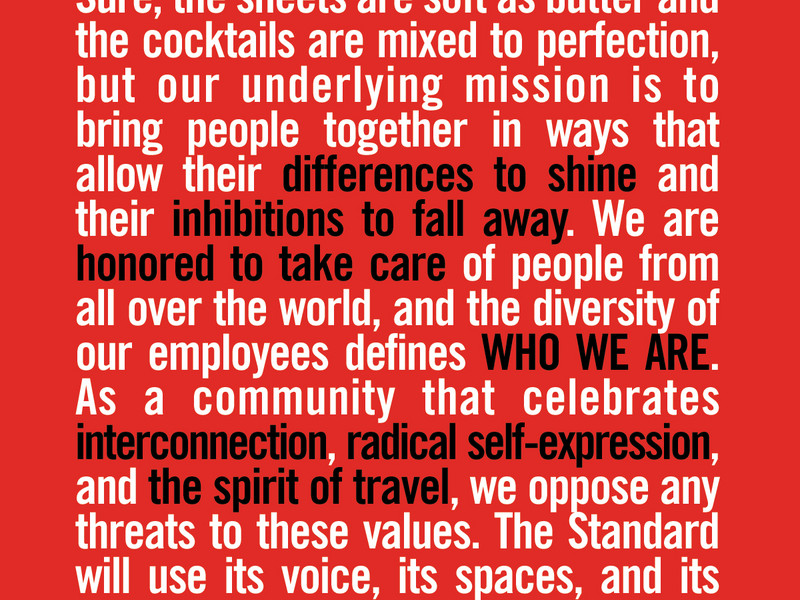

RK—Opera means great effort and that inspired me to start thinking of it as the most Black art form there is. The traditional structure of opera lends itself to fantasy, tragedy and opulence in ways that mirror many Black experiences. Black people have long starred in operas but the roles written for Black people are few. I go to the opera every now and again and I’m usually one of maybe ten Black people in the audience.Opera needs us, and we need operas that center the Black experience without the slave narrative or Prince Charming on a white horse cliché.

KS—I want to say exuberant, lavish, big things, with clarity and conviction. We live in ALL CAPS. We live in big worlds. Big things happen in our lives. It’s important to acknowledge living in a world as rife with earth shattering events as we do. Playing small doesn’t help anyone. Opera beckons and celebrates the epic, the mythological, the bombastic. This carves a place for the fullness and contradiction of living today.

KD—Which opera legends do you feel that we should be talking about more?

IU—Marian Anderson, Leontyne Price, Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle and the legendary Robert McFerrin Sr.— who was the first African American man to sing at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City, and who happens to be the father of Bobby McFerrin—and George Irving Shirley, as well as others I may not know the names of yet. We need to acknowledge operatic works by Black creators, including Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha. We need to be talking about Black creatives who have added to the legacy of opera as well as honoring elder Black composers, performers and creative artists who are under-recognized for their contributions to classical, contemporary, experimental, avant-garde and creative music and musical theater, such as Dr. Undine Smith Moore, Joseph Boulogne Chevalier de Saint-Georges, Florence Price, Mary Lou Williams, Julius Eastman, Alvin Singleton, Ben Patterson, Bernice Johnson Reagon, Eubie Blake, Noble Sissle, Flournoy Miller, Aubrey Lyles and Jeanne Lee.

AHM—The first opera singer I ever met was the illustrious Shirley Verrett. My mother would say that the neighborhood listened to [her] voice sailing through the air shafts up and down the block. She sang at the Met Opera, at Carnegie Hall and all around the world. But she also sang at home. That was the key for me. Can a tremendous voice be a found object? It’s how your music seeps into you that matters. If it is all books and hearsay and videos on YouTube, then your socks will get knocked off when you encounter it for real. It’s an encounter between the performer’s breath and your breath. You have to go listen to the vibrations in the space with the maker sometimes. That is also what opera is all about.

KD—Where do you think opera is headed in the coming years?

AHM—With the passing of Toni Morrison, I think many of us feel a certain gratitude and sense of responsibility. I have a renewed sense of freedom. She wrote about the whole wide world by writing just about us in this world. She reminds us what the word “universal” really means. I think that is the future of opera—more views inside the total human condition, scoping more recent politics and more contemporary atrocities—personal and public—through the lens of big thinkers, daring writers, and bold musical styles. Plus all this, opera is expensive, even the most minimal opera. Instruments, live singers, a director or several directors, lights, costumes, sets and an awesome amount of musical preparation—opera needs someone to write its check and opera is a big spender. [It] will always remain a luxury and I think I like that idea. Writers, musicians and producers who continue to believe that it is worth the expense are keeping a portal open for all of us who want to think big and dream even bigger. My husband Jason Moran and I will score our first opera for orchestra and singers next year. I love to work with people thinking amazing thoughts, asking me to do unimaginable things before an audience. I hope people don’t think it always has to suggest something sexual, though it can. Telling basic truth is one of the most daring things you can do. That’s been true for art since forever. Nothing new there. We have to do that, and keep doing that.

KS—I am looking for an opera that tells glorious and horrific stories with grace, violence and beauty. How can we sing of Pulse, of San Antonio, of our borders? I am developing a new opera, an exorcism of King Leopold II and his reign of terror in East Africa. The piece uses Mark Twain’s King Leopold’s Soliloquy as a starting point to evict the deranged king from our present. I am interested in the residue of colonialism, imperialism and slavery in our everyday lives. Opera is the container I’ve found that is big enough for this question, for a ritual as grand and spectacular as an exorcism.

IU—I think more and more of us are claiming our space and innovating—as we always do—within opera and other ‘unexpected’ art categories. This is a great, beautiful, necessary and wonderful thing. Black American Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes wrote “...I’ll stand up and talk about me, And write about me—Black and beautiful—And sing about me, And put on plays about me! I reckon it’ll be Me Myself! Yes, it’ll be me.” Amen, Ase and So It Is. —END