Silence Speaks in Staccato

Edward Said wrote in his memoir Out of Place that “all families invent their parents and children, give each of them a story, character, fate, and even a language.” He, of course, was speaking in the context of a particular identity formulation that you both share: the experience of the Palestinian diaspora. Could you tell me a bit about what was invented for you, both by your family themselves, and the diaspora as a kind of family? And in that vein, what do you hope to invent yourself?

What I've learned from my dad, and the stories he’s shared with me, is that as an immigrant you have to carve a space for yourself that doesn’t already exist. I’ve taken that into consideration for myself as an artist. If you’re conveniently plugging yourself into something that's readily available then you aren’t really challenging yourself. Having to carve a space for yourself is a ubiquitous experience for many immigrants, not just Palestinians in the Diaspora. I think we have that in common with a lot of different groups as well.

It can often feel, when I speak to Palestinian artists and intellectuals in this country, that there’s a tension between Palestine as a kind of imaginary, or a symbol, and Palestine as it exists. How do you, and by extension, your work, navigate this relationship?

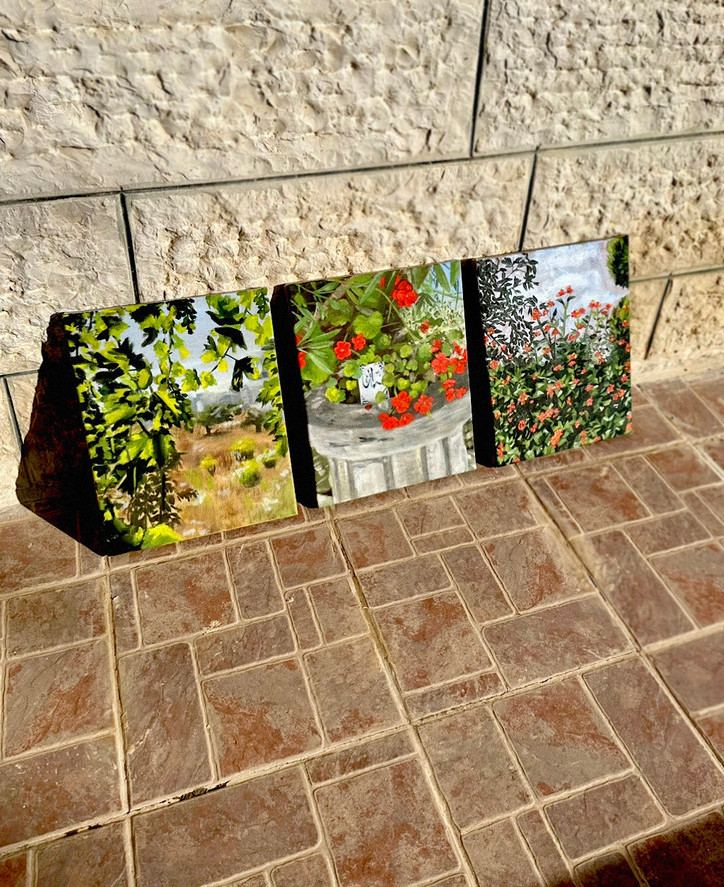

I’m always encouraging Palestinians in diaspora to visit the motherland if they've never been or haven’t re-visited in the last five years. Of course, this is easier said than done. Many Palestinians aren’t as fortunate as I am, because they’ve been exiled from ever being able to return. But I encourage this because there is a kind of fantasy-land that the diaspora projects onto contemporary Palestine. Even that term “contemporary palestine” is an oxymoron unto itself. But in my work I try to depict the actuality of the kitsch, the Abrahamic, the colloquial, and the agriculture that all exist in one place. The bizarreness of all those elements can be overstimulating: I often feel like it is a type of disney-land after all.

That makes total sense.

Yeah, it’s bizarre: you walk out of the church of nativity and you see several store fronts that have been there for ages, and they have this huge coca-cola banner because they’re being sponsored by coca-cola.

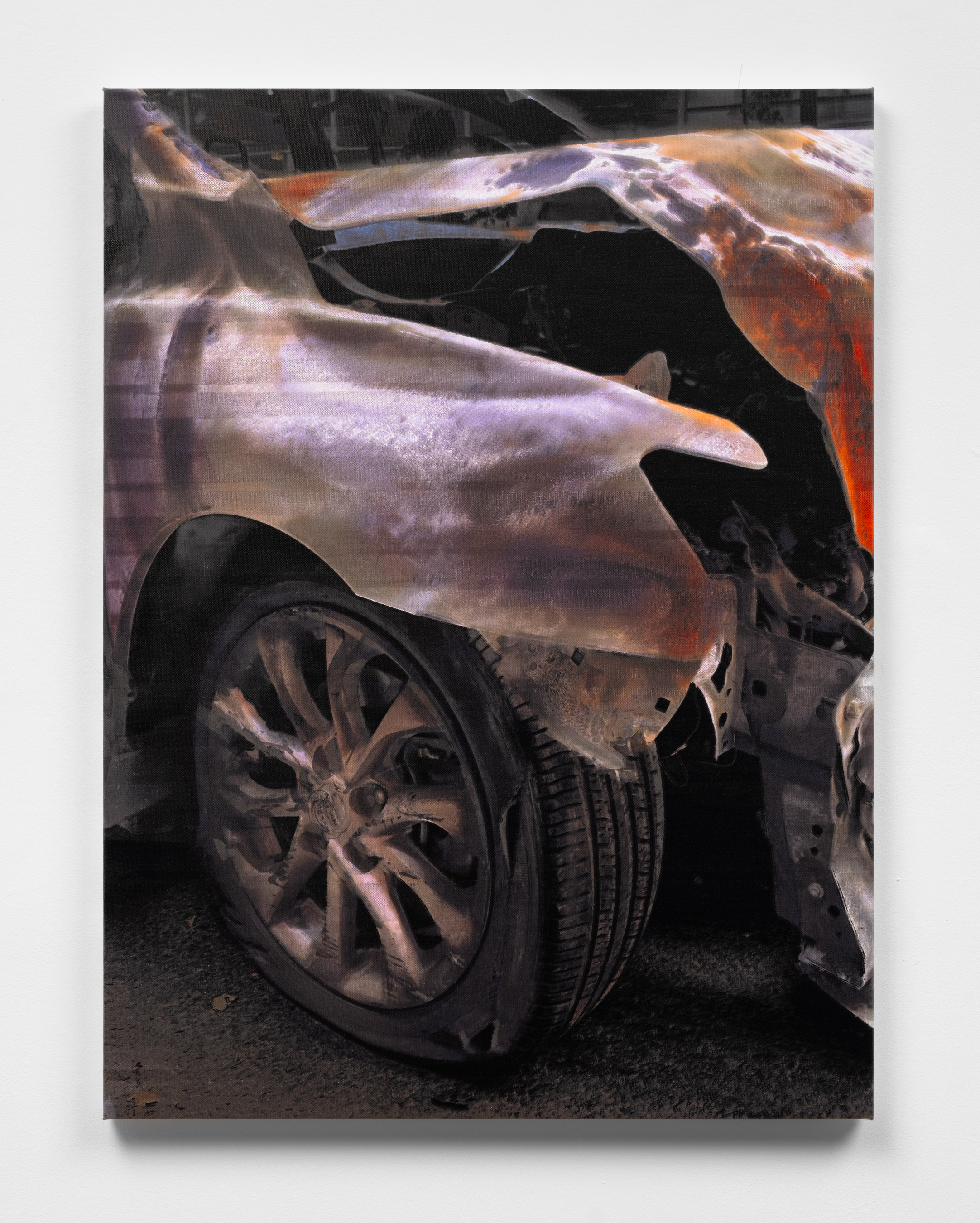

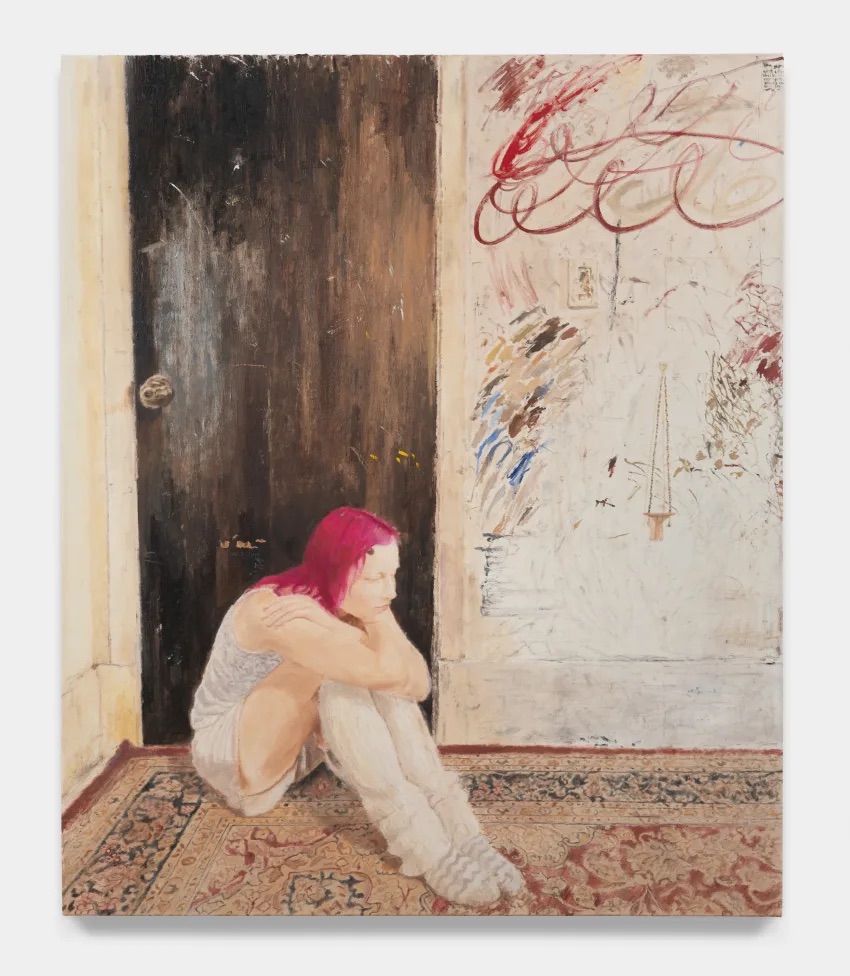

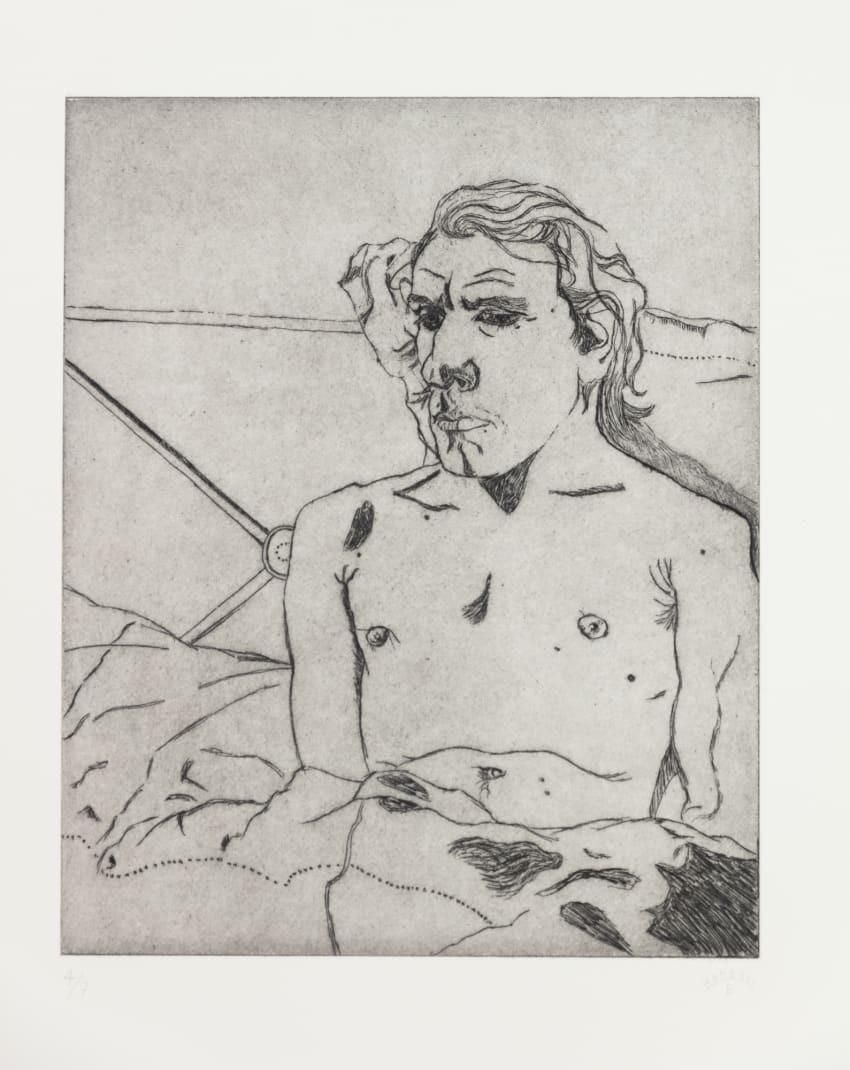

Untitled, 2023.

Right, and I think “Disneyland” is an interesting descriptor given the corporate element. I know your work in the past has been invested in the ways in which corporations and globalization interact with and have affected pre-colonial culture.

A lot of the disney stories themselves were derived from Abrahamic faith tales.

What was it like moving between St. Louis and The West Bank as a kid? Did you experience it more as a kind of liminalism (an in between-ness) or more of a full immersion in both, or neither?

Before the age of cell phones and the internet I spent a lot of time outside and exploring the land. I was able to walk everywhere in the area I grew up in America— I didn’t have a lot of constraints like residential streets leading to a main street. I’d spend a lot of time hiking. That isn’t the case in The West Bank. You can only walk in the confines of your village. That’s not to say that there’s a gate around the village, but you just know the boundaries. If you strayed too far, you’d be trespassing into a neighboring settlement which would cost you your life. Those types of severities were so normalized I didn’t understand the concept of apartheid as a kid. You know those types of stories your parents would share with you, like “if you do this or don’t do this the boogeyman is gonna come after you?” It felt like that: if you go too far, you’re going to be shot by the boogeyman, a.k.a. a settler. That was my understanding of what apartheid, that difference, was as a kid.

Can you explain what you were trying to express with this piece “Noman’s Land” from your series At Home in Your New Home? I find it quite powerful.

I feel like every American artist should take the opportunity to reinterpret the American flag through the lens of their own relationship to it. I made the piece in 2019, and it was my way of grappling with the anti-arab racism and islamophobia being propagated in America by the Trump administration with the “Muslim ban” that he issued. I remember when I got the work framed, the employee was so offended by the stars being opted out for the Keffiyeh and the shades of Arab complexion for the red stripes. And I asked: how do you identify with a land or a place without its stifling bureaucracy? We give meaning and purpose to a state, and if we rely on it being the other way around, we’ve become complicit with limitation and indoctrination.

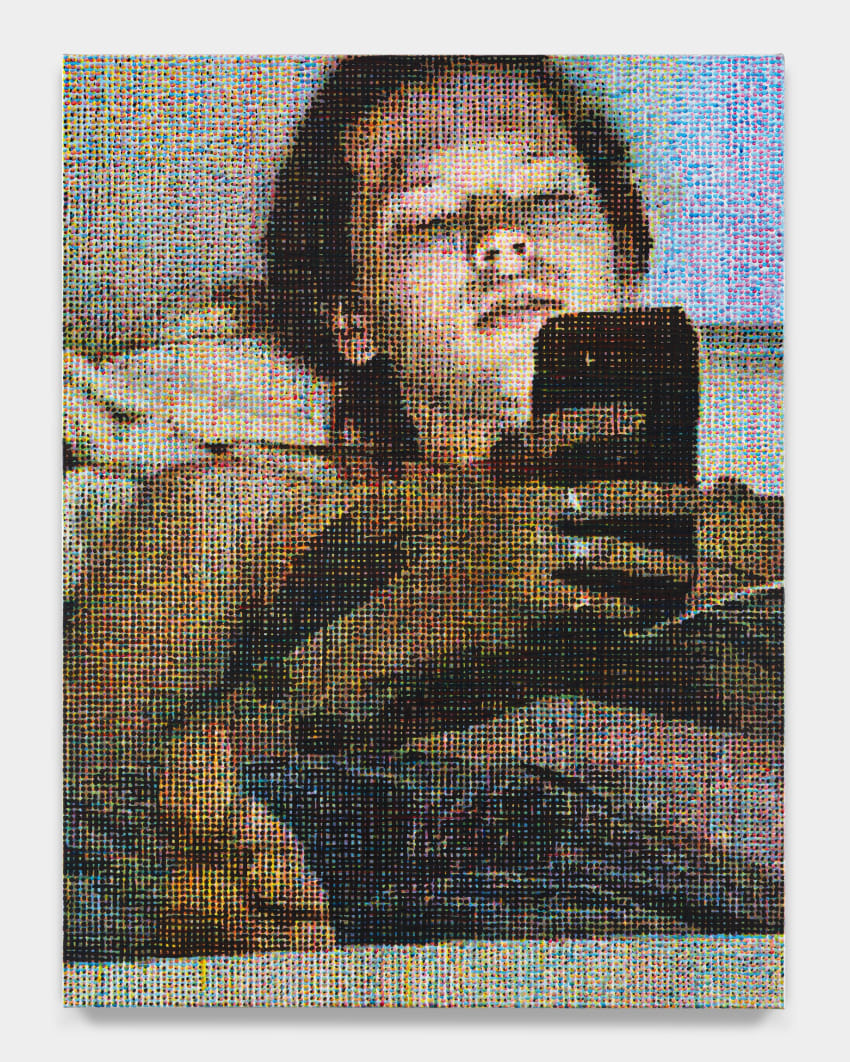

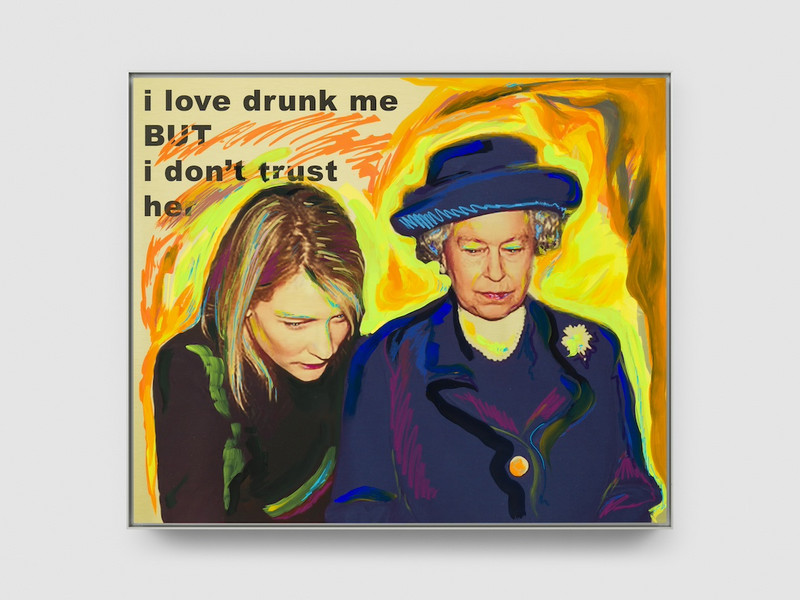

Noman's Land, 2019.

That’s profound. And obviously the piece has taken on more urgency given the events of the last few months. Sadly it doesn’t surprise me that the employee was offended, but it’s good that you challenged them.

Yeah. I could tell that she wanted to make an excuse in order to attempt to not service it, like give a technical reason it couldn’t be done, claiming that it was a “loose object.” I was like, “why don’t you just make the frame for me and I'll keep the piece and mount it myself.” So they couldn’t legally say that they refused to service me [laughs].

How do you feel about the radical shift in discourse following October 7th? I'm curious particularly how you as an artist, a mode of being so intrinsically tied to expression, feel about the turbulent mass of attention being brought to Palestine and its history. Does the pressure to speak out feel stronger than the pressure not to speak out? Have you found the pressure to align yourself with any particular identity or political movement oppressive?

It gives me hope for my people and for humanity that there’s unwavering support for Palestinians that hasn’t been present before because people are becoming aware. I’ve taken it upon myself to be assigned with two tasks along the way. One is “attraction, not promotion,” and the second is to be completely authentic in the journey of doing so. When I learned that people became gravitated to supporting our liberation through the humanization of my people, I realized I just have to continue story-telling through art-making and my experiences. I think that things like that are only oppressive if you listen to people’s criticism along the way. Many people have been trying to police the ways in which I highlight humanitarian and societal issues. My response is to remind others that they have their own ability to represent the issues that they want to, and that everyone has a role in this. The radical shift in discourse hasn’t been limited to just Palestine, now we’re talking about collective liberation that calls for justice to be brought to the people of Congo, Sudan, Syria, Iran, and marginalized communities across America. I think that’s the most radical shift in discourse since October 7th.

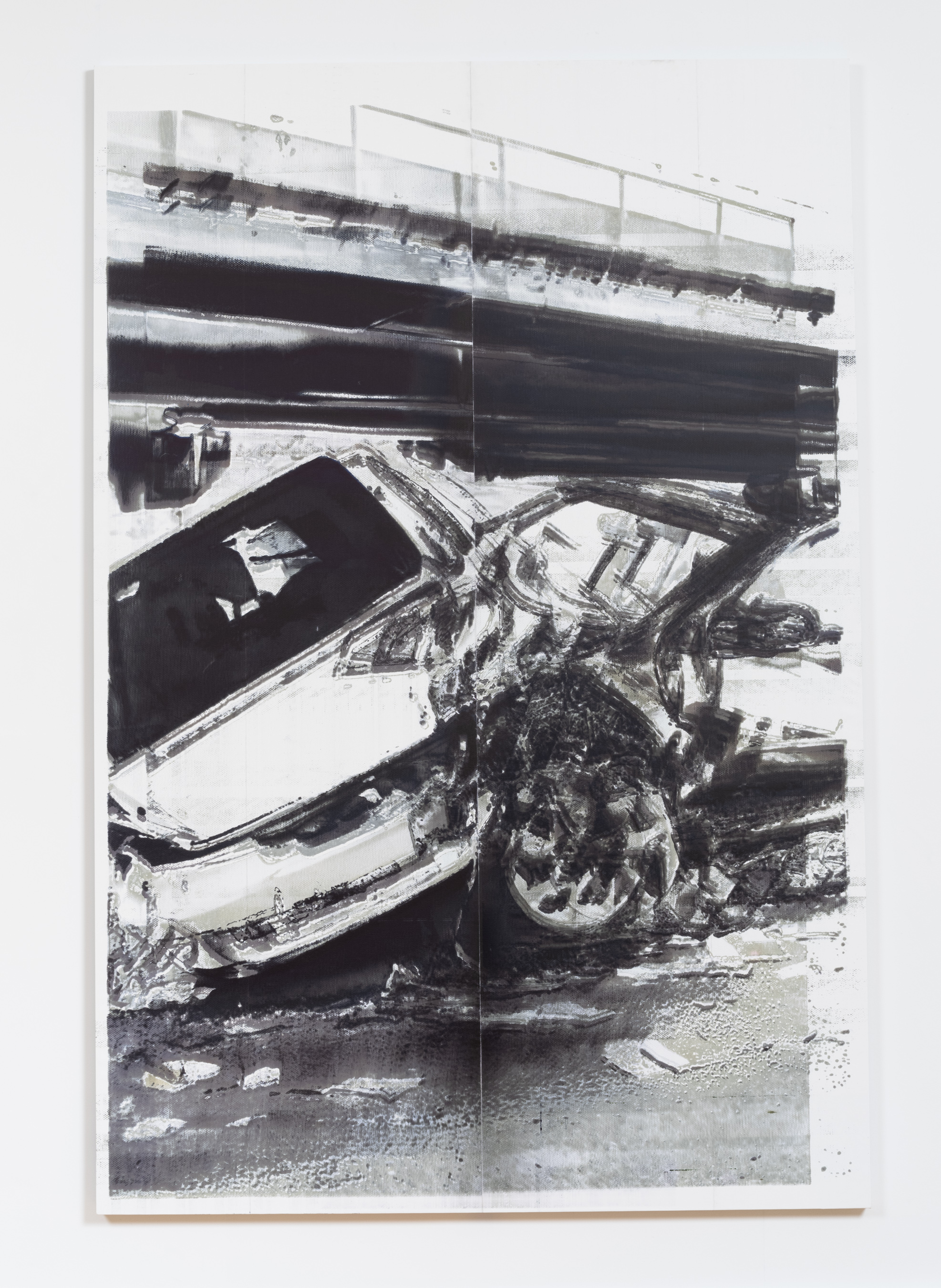

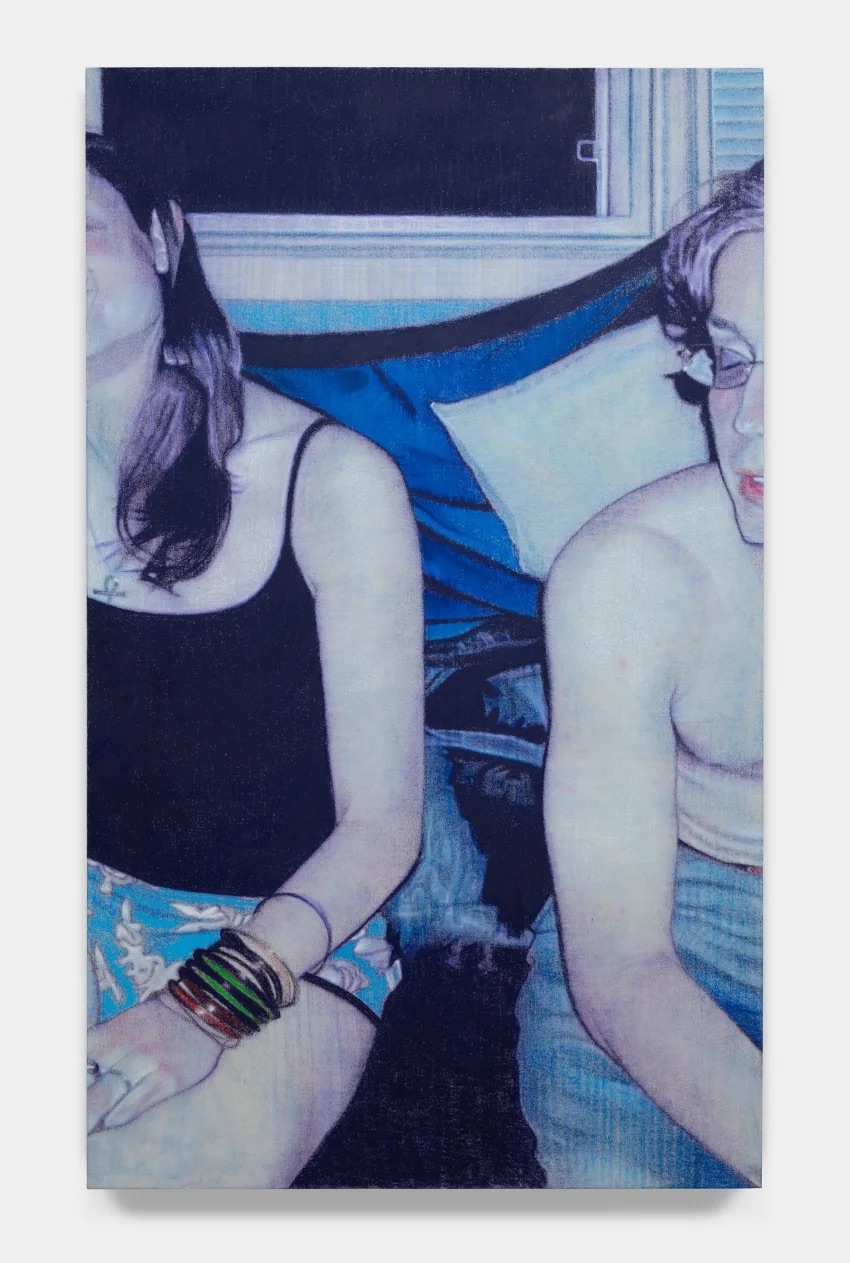

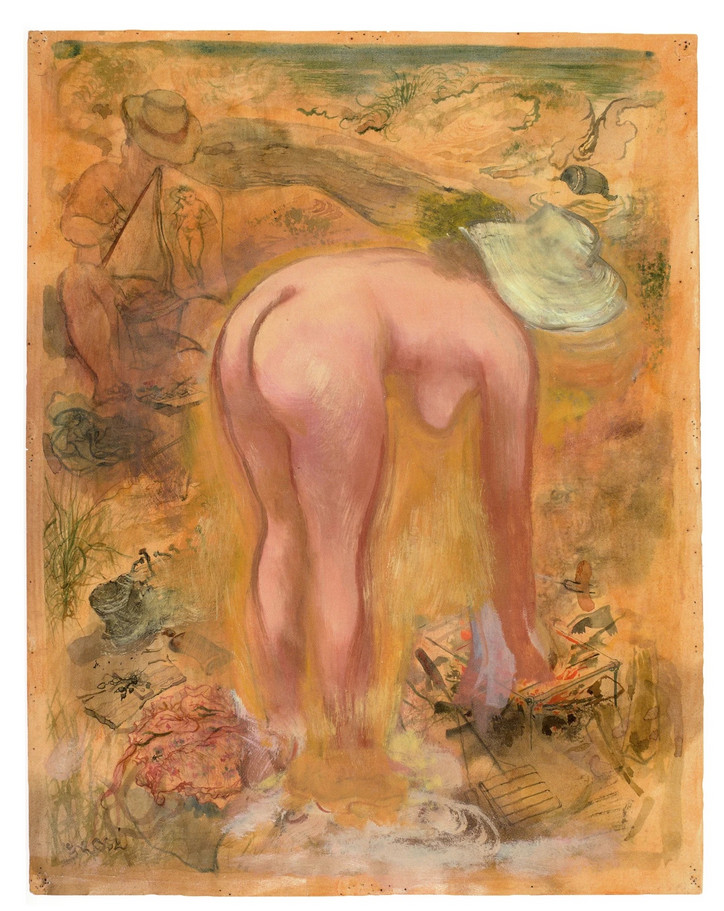

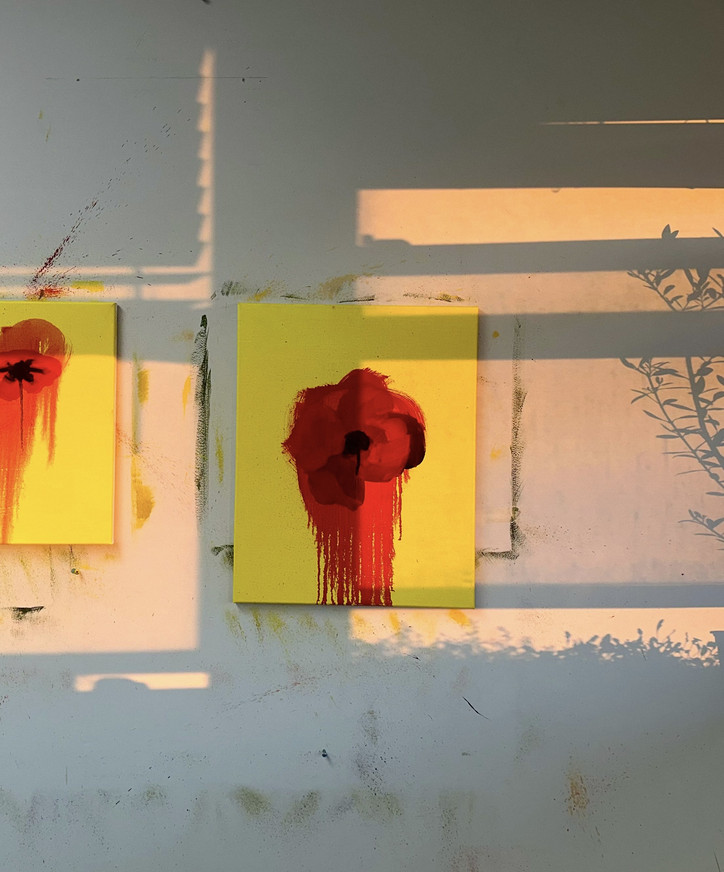

Untitled, 2023.

I saw that you’ve been bringing your paintings to protests, is this a common practice for you? I’m curious if you could delve into what that relationship to art in a political/public space is like for you, as opposed to a fine art space like a gallery.

I’ve been going to protests since I was in a stroller, and I had given up on demonstrating for years until this most recent uprising. I was in my studio, painting, feeling hopeless and contemplating if I even wanted to tap into the first protest after October 7th. I was painting a poppy flower when my home-girl hit me up and asked me to join her at the demonstration. So I just took the canvas off the wall and held it up at the march. I’m very anti-flags and I reject nationalism, so this forced me to think of more ways to approach identity free of state-politics. After I’d gotten resignations from galleries who didn’t want anything to do with Palestine or a Palestinian artist, my purpose shifted towards activism. I didn’t want to compromise being an artist just because I lost opportunities or because I'm in immense grief, so I've been considering how to make protest a performance art. After all, M.L.K. was the greatest performance artist of the 20th century.

Totally. There is an art to protest. And I think your praxis speaks to a lot of the criticism of the fine-art world: the notion of art as purely decorative, of a piece as an ornament.

It’s also an institutional thing. Paintings are often hung up on a white wall, attempting to be pristine. There’s something grittier about taking it outside on a walk as the piece collects outside contaminants that otherwise wouldn’t appear on it. I’ve been working on these poppy paintings, which have now become a series, because the poppy is the national flower of Palestine. Every protest, demonstration, or activism meeting that I take part in, I’ll take a new painting and hold it up in place of a sign or something with words. I’m considering how the environment I'm in is a kind of installation: it’s giving context to what I stand for. And I want to incorporate the poppy to be a signature element in order to reference our Palestinian landscape. What I imagine for this ongoing series is that for the next spring protest I’ll distribute the collection of poppy paintings that I've created along the way to protestors so that we hold it up and become a field of poppies during the spring equinox.

Wow. That’s beautiful, I didn’t realize you had that meta-intention. That’s a powerful image. On the topic of expression, what does it mean to you to make art in the midst of violence, especially an on-going violence like that which has existed in Palestine for so long? This brings to mind the Palestinian poet Marwan Makhoul’s poem which made the rounds on social media recently:

"In order for me to write poetry that isn't political,

I must listen to the birds

and in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent"

I know that you went to the West Bank to continue your practice last summer, and also have recently made another trip there. I’m curious how these experiences may have changed your perspective on this topic, if they have at all. This also ties into my previous question about the cacophony of chaos that is public discourse at the moment, which is its own “warplane.”

Yeah. That was one of the first poems I saw circulated. I think a lot of artists that work in the realm of politics and identity resonated with it. Do you remember the combat field musicians that they taught us about in history class? I’m starting to realize that my favorite place to be an artist is where it’s most dangerous to be an artist. I feel like I've been assigned a new role amidst the chaos that’s beyond my control, the role of art-journalist: making art in real-time, touching physically whatever’s on the ground, disdaining the pillars of smoke off in the distance. I think this most recent experience made the notion of art-journalism really immediate and urgent. It felt really free too. There was also a lot of censorship I had to be weary about. But when it feels like you have nothing to lose, you’re going to be most vulnerable and create really good art.

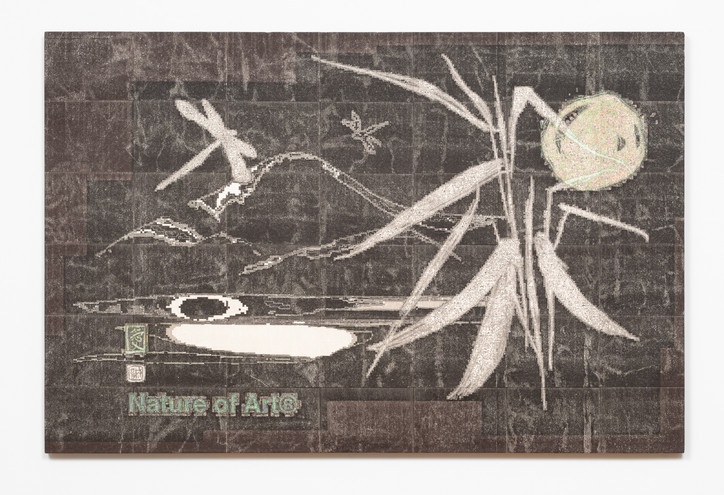

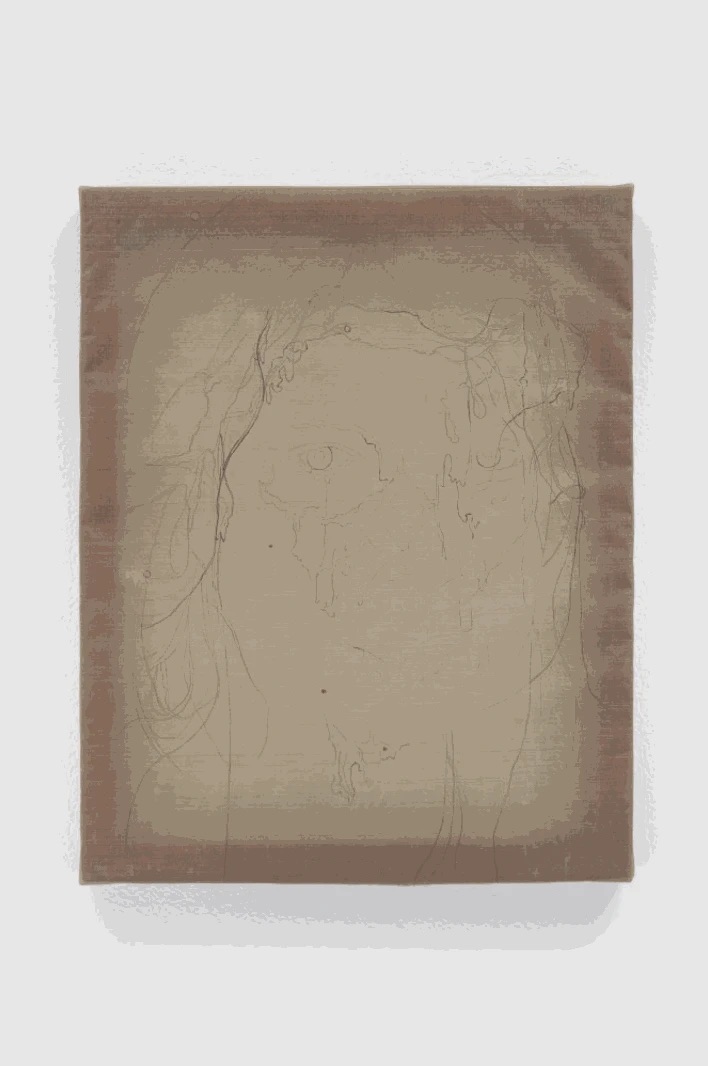

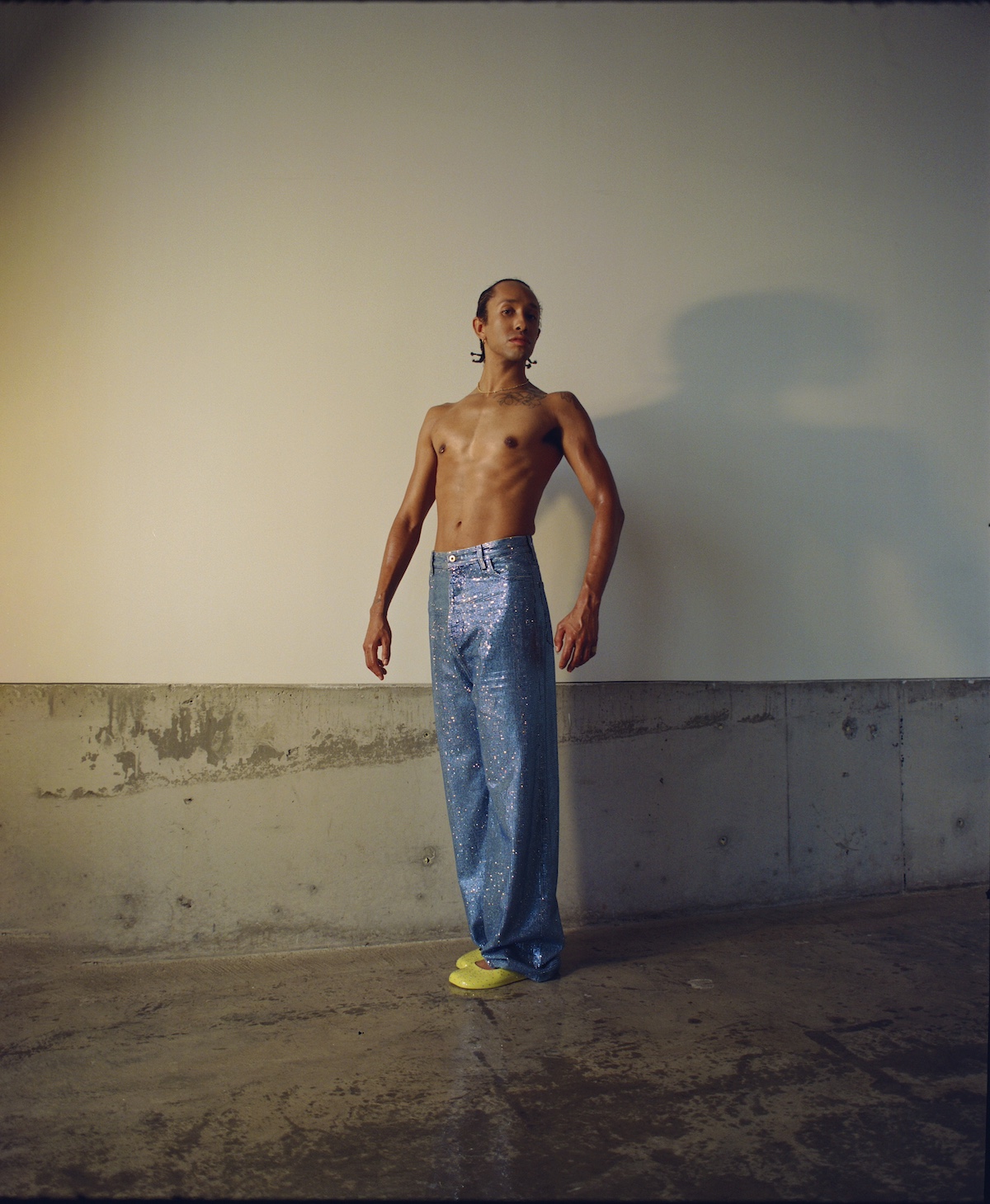

Untitled, 2023.

My last question has to do with the state of the art-world more directly. What kind of relationship to the art-world bureaucracy have you had in the past, and has it shifted in the last few months, if at all? If it has, how has this relationship changed?

What’s been going on in the last few months is not a new issue that I personally have been dealing with in the art world. The bureaucracy, censorship, economic, social, and environmental injustices are all interconnected. I see this issue as a moral litmus test that has bled into the art-world, which should be the place to hold this discourse. So much of the art-world is like “we don’t want to be involved in politics.” But the ongoing art-movement in the last decade has been about identity politics, so people have been picking and choosing which identities and stories are palatable and worthy of being drawn from. And has that changed as of now? It’s still definitely in effect, but I hope that this isn’t swept under the rug. I know a lot of artists, the real heads out there, aren’t going to be ok with it being swept under the rug. Because they understand how hypocritical it would be considering their practices, which involve so much political identity discourse.

Right. So you feel like it’s really only a matter of time, at this point, before these things change.

Yeah. Every week now a new story appears about another art-group being canceled or resigning from some sort of show. And there’s so many stories that haven’t been covered of decisions of artists to not work with a gallery as a result of it’s hypocritical stance on Palestine or censoring Palestinian artists, even if those artists haven’t made a public statement about it. I think what’s really beautiful about what’s going on is the solidarity network that a lot of artists are feeling compelled to execute.

I totally agree. Thank you so much Saj.