Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Paul Hameline — It involved several coffees, a bunch of beers, nighttime, daytime. Several back and forth, it was all quite similar to a tennis match really. I would send Paige one image, she’d reply to me with another one. Same with texts, Paige would send me a text excerpt and I’d reply by sending her another one. Eventually things started taking shape in an organic way, and we would simply orient the narrative in a direction rather than another.

I’m sure you were uber excited about all of the artists included, but was there one in particular you were looking forward to presenting to this local audience (maybe new to them)?

Paige Silveria — That’s obviously really hard to answer. Though I want to say that I found Gogo Graham’s self portraits really special. I met her years ago when I interviewed her about her fashion show in New York. As a trans Latinx fashion designer and artist, her runways were these incredible, conceptual presentations. You really felt like you were immersed in an art performance. Recently, I saw that she’s been taking a bit of a step away from fashion and focusing on her art, especially paintings. So I reached out to see if she might want to show one with us in Paris. I love these two portraits she allowed us to include so much. One is her when she was this adorable little kid with big ears and the second is later, as this like glamorous icon.

And this wasn’t your first show in the space, right Paige? How would you compare the two?

PS — The first thing I did was a curatorial collaboration with Arcane Press magazine for the release of their first issue. The aesthetic was a bit darker and moodier and really focused on the artists included. This show with Paul was a bit more personal and organic. We spent months chatting between the US and Europe and with coffee on walks when I’d finally returned to Paris. We would send artists and work we loved and discuss the complexities of why they made sense for this little world we were creating. Then trying to articulate what the world was turning into with literature … It was a really special and fun project to do between friends. And we really took our time.

I loved coming by the night before the opening when unfinished and seeing it the next day, how late did you stay?

PH — Not so late after you left, must have been 10-10:30. Once we were done, we went for beers, some cigs and giggles.

PS — I love the install. It’s so exciting to see everything together finally after staring at images on your computer or phone for months. Things are tangible and you can start to really craft the physical world that previously was only in our heads.

What was your favorite part of curating together?

PH — The thought process, the research, the exchanges etc. Paige showed me artists and authors I didn’t know, I’d reciprocate by making her discover some she wasn’t familiar with. Sharing is caring. We obviously are two different people with our own ways of seeing and experiencing, so merging the two in order to give birth to that show was a great experience.

PS — It’s been a while since I was able to put a show together with someone from the inception. I really loved to be inspired by his way of thinking and being introduced to new communities of artists. It was also pretty exciting when we realized that our separate ideas were super similar and the vision was happening in tandem. Things worked so smoothly; we somehow emerged with the same aesthetic in mind.

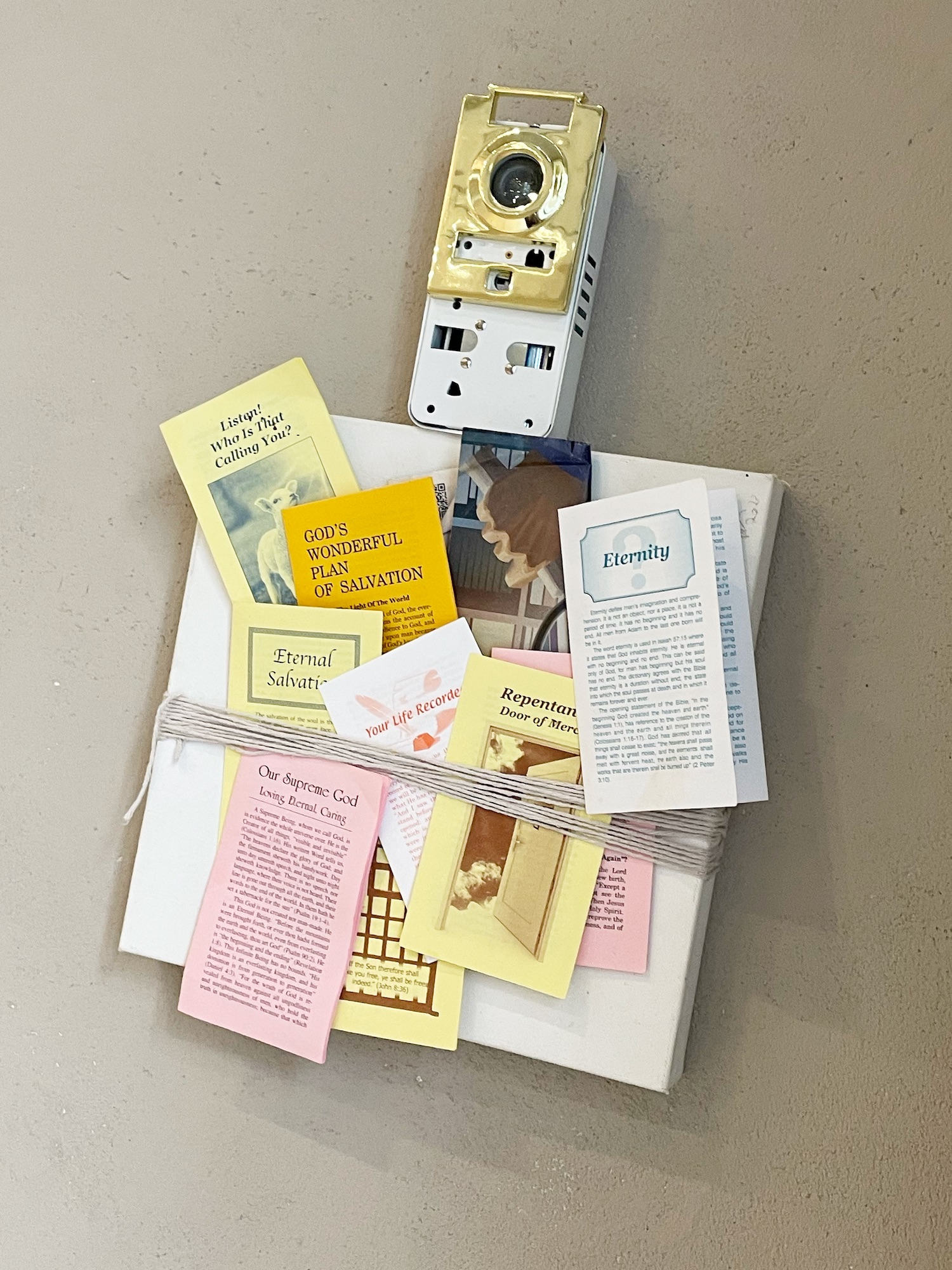

What led you to the title ‘Preservation’? What are you preserving?

PS — The title was pulled from the excerpt (in the press release for the show) from Robert Pirsig’s book Lila: An Inquiry into Morals. With the title, we’re analyzing civilization, societal structure, moral grounding — preservation of what exactly? Of whom? At what cost? And why? It’s less of a statement, or a desire to preserve anything, and more of an inquiry to begin the conversation.

In an interview I read recently, Hans Ulrich Obrist said that “good curation is working with someone who can do something you can't.” He also called curation a kind of junction-making, creating these avenues where people and ideas meet and interact. Do you agree?

PH — That goes without saying. The basis of any relationship is to give and take. You have something to offer, and the person sitting in front of you has something to give you. We grow through our relationships and encounters, from a lover to a stranger asking you for a lighter.

PS — My favorite take away from Marx was when he said that human relationships are the point of our existence. I think that’s any conversation and exchange, even reading the book of someone who’s past … With these shows it can be so exciting bringing people together. A while back I did a Good Taste show in LA and was showing work by two really iconic artists, Erik Foss and Erik Brunetti. Although they’d been aware of each other for over a decade, they only finally met when we began installing this show. It was really cool to listen to them discuss things from over the years that one another had done that’d made an impression on them. Even just small connections like this are a part of why I love to curate — not just about making sales!

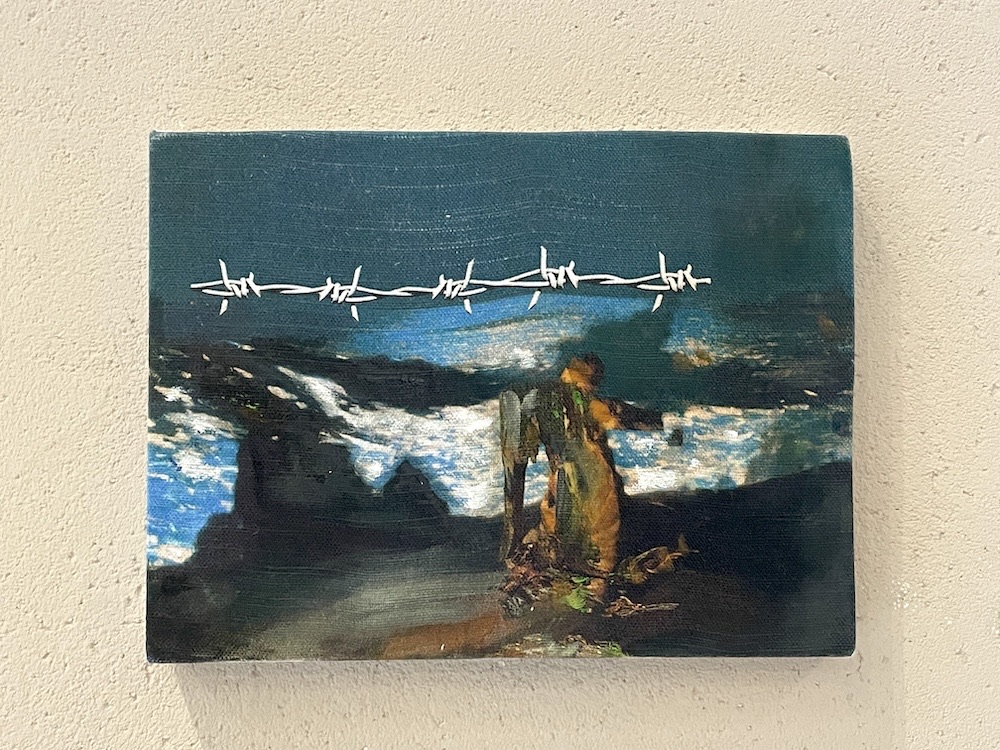

What conversations are you hoping to nudge into existence with this show and those to come?

PH — The way I perceived it, it’s about how civilization reached a point of no turning back, it’s about creating some kind of world within oneself, against the turmoil present in today’s world. We tried to create a safe haven, some kind of fort. A dystopia slowly leading back into utopia. A bit like Peter Pan and his Neverland. A feeling of compassion, of affection, of love followed. Memories of childhood, the importance to dream and to use one's imagination, allowing us to become our own architects of wonders. Let yourself dream. Shake up the ‘younger you’ hidden in your own eyes and past. The one the world tells you to silence and forget too often. Do not let that little guy disappear from your life. It's about having fun, smiling, playing. Keep that spark burning like an eternal fire.

PS — Yes, I love that.

Isabella Fox Arias — How does language play into your work? Despite using a visual medium, language is still omnipresent throughout.

Eimear Walshe — The process of making ROMANTIC IRELAND started with writing, and I am very word-oriented, even as a visual artist. Writing comes up high in my communication fluency areas, so my challenge for this pavilion is thinking about the three different things produced.

The first part is the libretto in terms of its development, and that's obviously a writing process. But the challenge with the other aspects, like the video and the sculpture, was to think through, you know, the performers don't speak; they communicate just through gestures.

That was a challenge because I want to get more fluent with working just through gestures. What better way to do that than through dancers with their own vocabulary? I was really lucky to get to work with the dancers, performers, actors, and musicians who convey without words. Then, through the building, it was like thinking about retelling a part of history just through the material itself.

I'd love to hear more about constructing the story of the building.

The libretto text was the starting point and, I suppose, is also like the temporal anchor point in the sequence where the video was set. It's the biography of a building — the building site is the before, the eviction is the destruction of the life of the building, and then the ruin is the afterlife. The libretto about an eviction became the fulcrum of the narrative arc of the pavilion. It's central and primary, but I think it's also something that I try to challenge myself with. That's why it's so special to get to work with other people: you find out their languages, their fluencies, and their modes of conveyance.

Have you worked with dancers before, or is this your first time working so heavily with just a movement-based language?

Yeah, this is my first time. I got Mufutau Yusuf on board at the very start. I did that because, in his work, he has the ability to communicate incredibly large volumes and intensity through very minimalistic gestures. Some of his works involve really explosive, hugely energetic movement, but then others involve microscopic movement, like having individualized control of a whole sort of fan of muscles on your body. That extends into the kind of narrative that he is able to make through those really microscopic movements. I remember seeing one of his performances that involved moving a bicycle a tiny bit backward and forward. It's just incredibly beautiful. That ubiquitous movement captured and repeated was really of interest to me in terms of the earth building. The brief or the remit for the movement and why I was so comfortable working with Mufutau as a choreographer was I don't really want there to be dancing. I wanted to be built around the types of movements required for this kind of labor and building practice.

Working with Mufutau, Rima Baransi, and Gallia Conroy, who were the crew members with strong backgrounds in dance, was really inspiring. They just have a different way of creating. I was able to write the scripts really differently than I usually would; I'm usually a little bit over-contrived. People who are improvisational dancers are going to challenge that. For some parts of the script, I just bought laminated photographs of pieces of furniture.

What kind of furniture did you bring?

One of the really important ones was a phone stand, which is a funny mid to late-20th-century piece of furniture that you'd have in your hallway. There's a little door, you put your phone book in a little press, the phone is up high, and there's a little place to sit. That appears in some of the photo documentation of the work. Erin plays the harp, so she needed a harp stool; my businessman needed a big mahogany desk, so we made that out of our bodies, and the landlord wanted to shit on everyone, so we made them a toilet. That was incredible because it was not an area of aptitude for me. It was really special getting to work with people who were not even exclusively in that field but who have such strength in that area.

That's wonderful! I was also interested in your choice of using masks for your dancers. I found it powerful that the identity was erased from the dancers, and instead, they became almost monster-like.

Yeah, I mean, those masks have really different associations for different people. People asked me the least about the sort of monster alien end of the spectrum, and I'm excited to talk about that, actually.

Really? It was my first thought watching the piece.

Yeah, I guess there is a spectrum of associations with those masks. Their primary use is their fetish objects, and they're from a latex company that produces custom whatever you want sort of latex pieces in any color. They're in olive green, so they also have an association with Ireland, the military, and the colors that were worn by volunteers in our revolutionary history. Also, any kind of face covering is often associated with clandestine activities. There's some kind of line between deviance and criminality when you have to cover your face because of what you're doing. Thinking about the different types of external forces that create the necessity for that but also thinking about, especially the fact that they all wear it even though they're all from different historical and class positions, this kind of universal marker.

The monster bit is really relevant because I'm thinking about the way that colonized people, whenever they resist in any way, shape, or form, including peacefully, are constructed as terrorists. That's definitely something that's at play with this. These constructions of forced clandestinisation, deviancy, and the relationship between armed resistance and liberty. All this is painted on them, and then they act out a soap opera. I suppose what I'm asking of the viewer is, can you when you see them go through all these daily activities, can you identify with them anyway, even though they've been othered by this costuming?

You mentioned otherness, which I felt while watching your work. You piece made me think about otherness and its relation to being a queer artist. You are non-binary and your work deals a lot with transient middle space that exists between two extremes. I’m thinking about how your work deals with coming from a land that was both the colonizer and the colonized. There's not really a question there.

But you're onto something aren't you? You certainly are.

Yeah, this is what your work has been making me think about.

I think there are two things with that: the interest in forced clan destination probably does come from thinking about the kind of bargains that you cut, and there are the invitations to self-betrayal, which includes betrayal of your history, betrayal of your ancestral struggle, and betrayal of your peers. That's certainly something that I'm thinking about with this. What you were saying in terms of Ireland as a colonized, a settler colony, but also the agent of, certainly in a really extensive way, religious imperialism. We tend to be a bit less keen to discuss.

Then secondly, the assistance to the extension of, and the aiding of, for example, US imperialism. We are a colonized nation that aids in the colonization of others and has learned nothing. In terms of what that has to do with being non-binary, maybe there's something very kind of simple in terms of creating a narrative film where there are no goodies or baddies. Why is Ireland so keen to discuss its victimhood in relation to colonization and so shy of or even in denial of how it perpetuated it? Part of it is because narrative framing doesn't allow you the complexity to have both, and that's also the case in lots of other kinds of categories.

Abstraction in Reverse

By Kyle Carrero Lopez

after Takako Yamaguchi

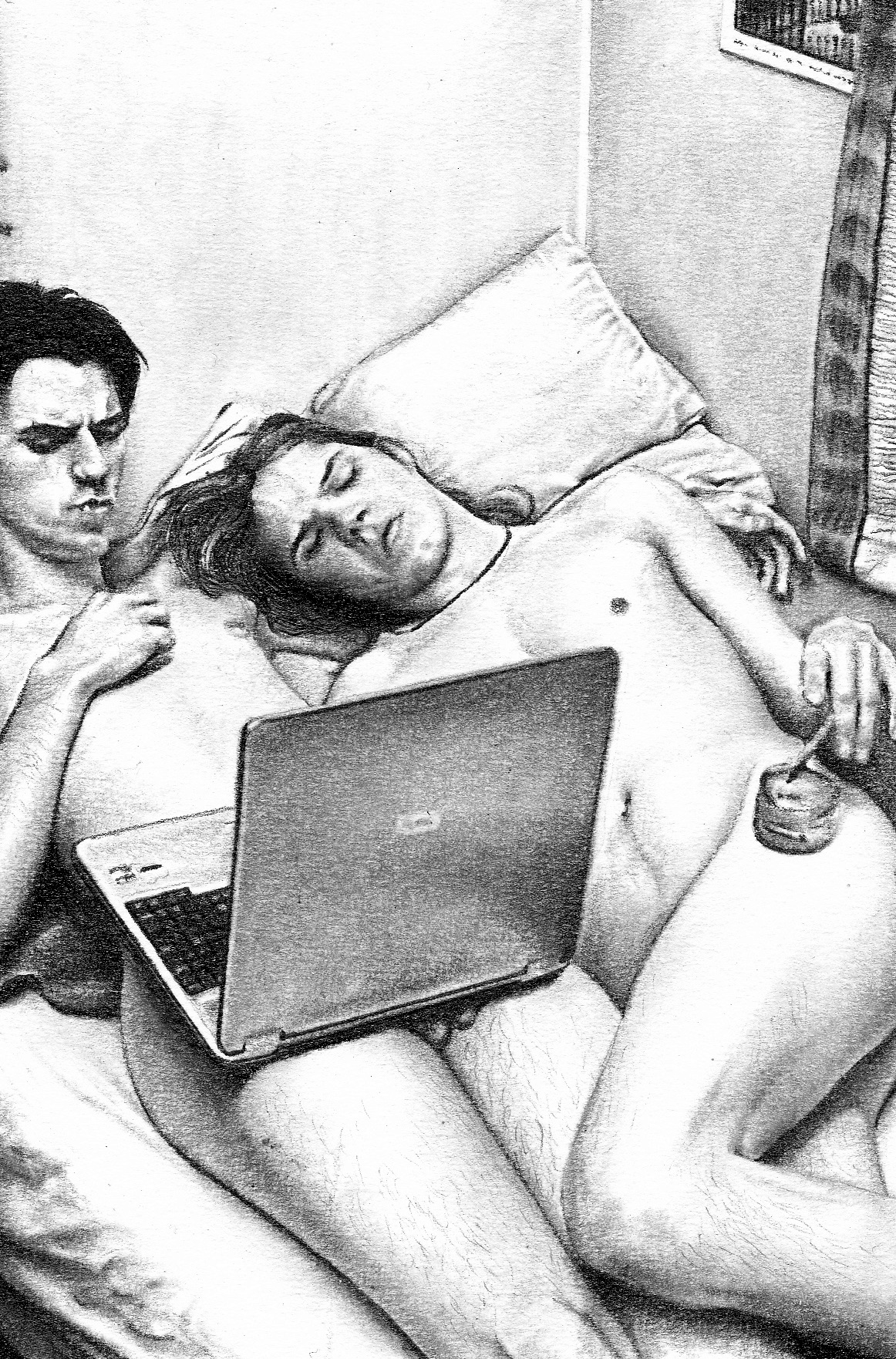

The laptop logo looks like a cartoon apple

and the cartoon apple (in two parts) looks like a sideways

sort of jagged tooth below a pointed oval — its floating stem:

not simply oval but vesica piscis, fish bladder, the shape made

between two intersecting circles, heart of the venn diagram,

the heart itself in the center of one’s chest,

though leaning slightly left—an imperfect center—

the heart itself symbolized by a shape unlike the heart;

the false heart representing true feeling, true love,

its shape, in one telling, pulled from Aristotle’s theory of its shape:

three chambers with a dent in the middle,

and though we now know it’s four, the false heart isn’t so far off,

essence of the true shape there in the abstraction,

the true heart loosely similar,

the true heart on a lab desk pre-transplant

pump pumping the false heart’s trademark red,

blood-soaked comice-pinecone-misc. THING,

vigorous, and thick, and horrifying,

ours

“He Is Here!”

By Kay Gabriel

See: Sharon Hayes, “Ricerche: four,” 2024; ektor garcia, “teotihuacan,” 2018; Tourmaline, “Pollinator,” 2022.

Sharon Hayes seems patient.

She asks a lot of older people what they think is going on,

If the gains they fought for have endured,

where they feel safe and if they

think the world is better now or worse than when they were young.

These questions can be frustrating. I mean, I get frustrated,

sometimes, asking people if they think it’s a bad world

and why, and what to do.

Hayes’s interviewees agree the world is worse,

even, than the one in which they came of age, though

they don’t agree on why. They feel something disintegrate.

I’m paraphrasing—they didn’t say disintegrate.

A man acknowledges legal rights.

He’s Black, gay, looks to be in his late 70s.

Watching the moral panic grow—

paraphrasing again—

he suggests the win is fragile. Where’s safe?

Home. Where’s home? A retirement

community in Tennessee. We used to be so afraid

of a liberal world, that it would subtract the force

of our critique, like shock absorbers on a car, or a

Katamari ball yes-and-ing its path across a surface

pounded flat. We, I mean, queers whose consciousness was

easy-baked in like 2012. We regarded with

suspicion the capacity of art to—what, exactly?

Challenge? Sure, if you put it

like that. I mean we watched people sharpen

critique while the relatively powerful repeated it, and metrics

like average inequality, average deaths per day

tunneled deeper into nightmare.

I’m trying to explain a feeling—dispiritedness;

the sense that pricking conscience

wouldn’t do much, even in highly trafficked environments.

Were we wrong? Hannah Baer called herself a “skeptic

at church,” about poetry, not art, but it feels similar:

suspicion about the relationship of content to changing

unbearable conditions. And not even poetry per se but poetry

readings, which can, sure, be dreary affairs. There’s your

ex on his phone. There’s a bad feeling. There’s a pile

of interesting people. Or it’s transcendent,

I mean, the words change something—clarify the obscure, offer

strength to the downtrodden, make productively

light of misery. Cecilia did, “sucking

and sucking,” wishing Chiqui would fall

on stage. Pamela Sneed remembered

Assotto Saint defiant at a funeral: “He is here!”

and I wept. It’s like: “Cecilia!” Patrick wept, when Nan Goldin

read Cookie Mueller’s “Last Letter” in the new Walking Through

Clear Water— “I know, I know, I know that somewhere

there is paradise … Courage, bread and roses,”

see, Hannah, I’m crying right now,

so I don’t hold your position.

Peter Weiss in Aesthetics of Resistance has

his antifascist fighters, exiting Spain,

study Guernica in the woods, and Amilcar

Cabral wrote poetry while he fought the Portuguese.

He died before the victory he made possible.

I could go on, even if the “art world”—a euphemism

for the class that holds the keys—shreds its revanchist wave.

I believe that that, too, will pass,

not just like that. I mean I think that people change their ideas about reality

faster than reality can change. I suspect they do it

faster even when together, which is why Hannah’s

right, it’s church. We’re moved to see each other

moved. It’s nice that the Whitney likes trans

women artists so much: Ser, Pippa, Tourmaline.

Tourmaline’s “Pollinator” video is stunning, her orchid

headdress, her Marsha research. So are ektor garcia’s

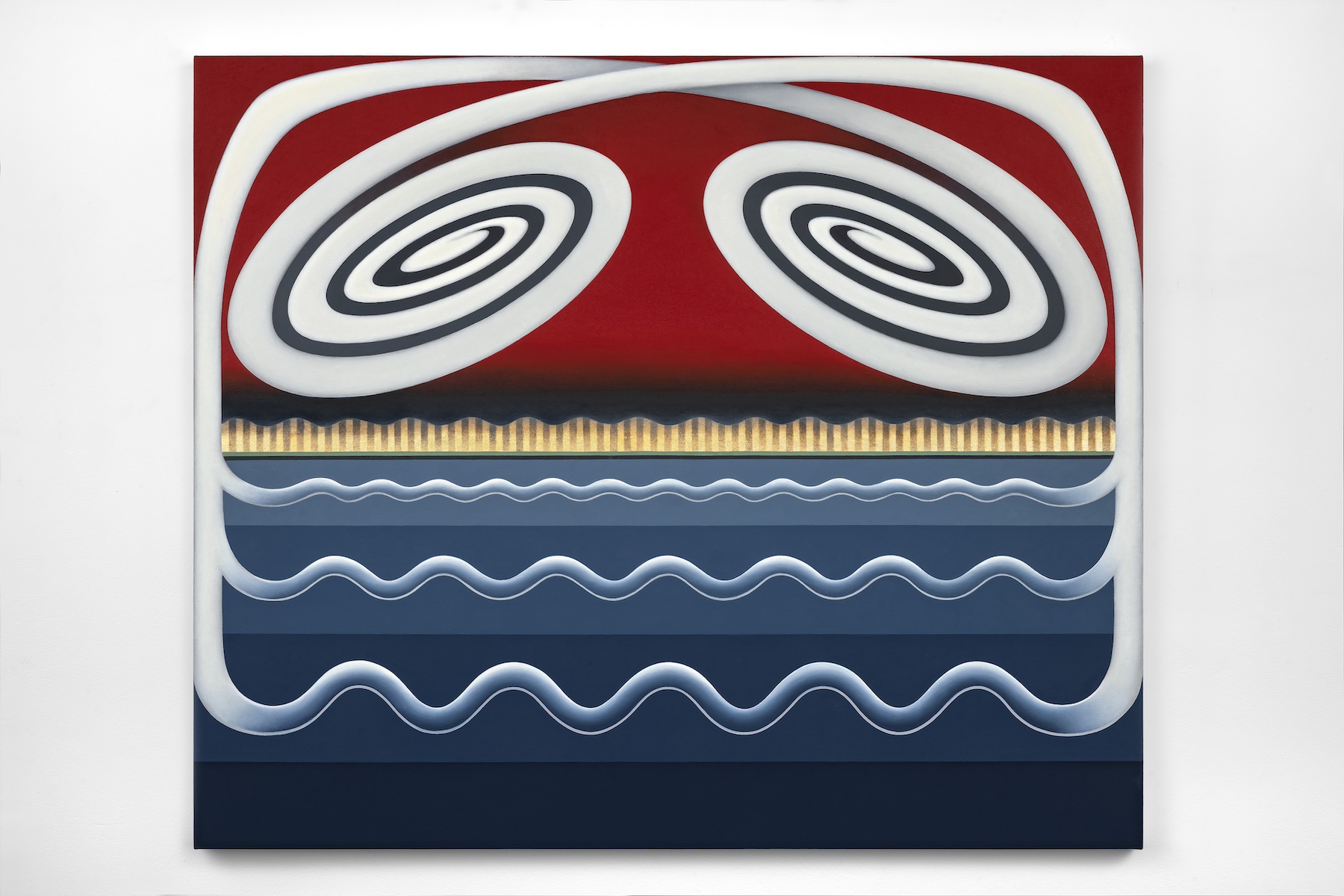

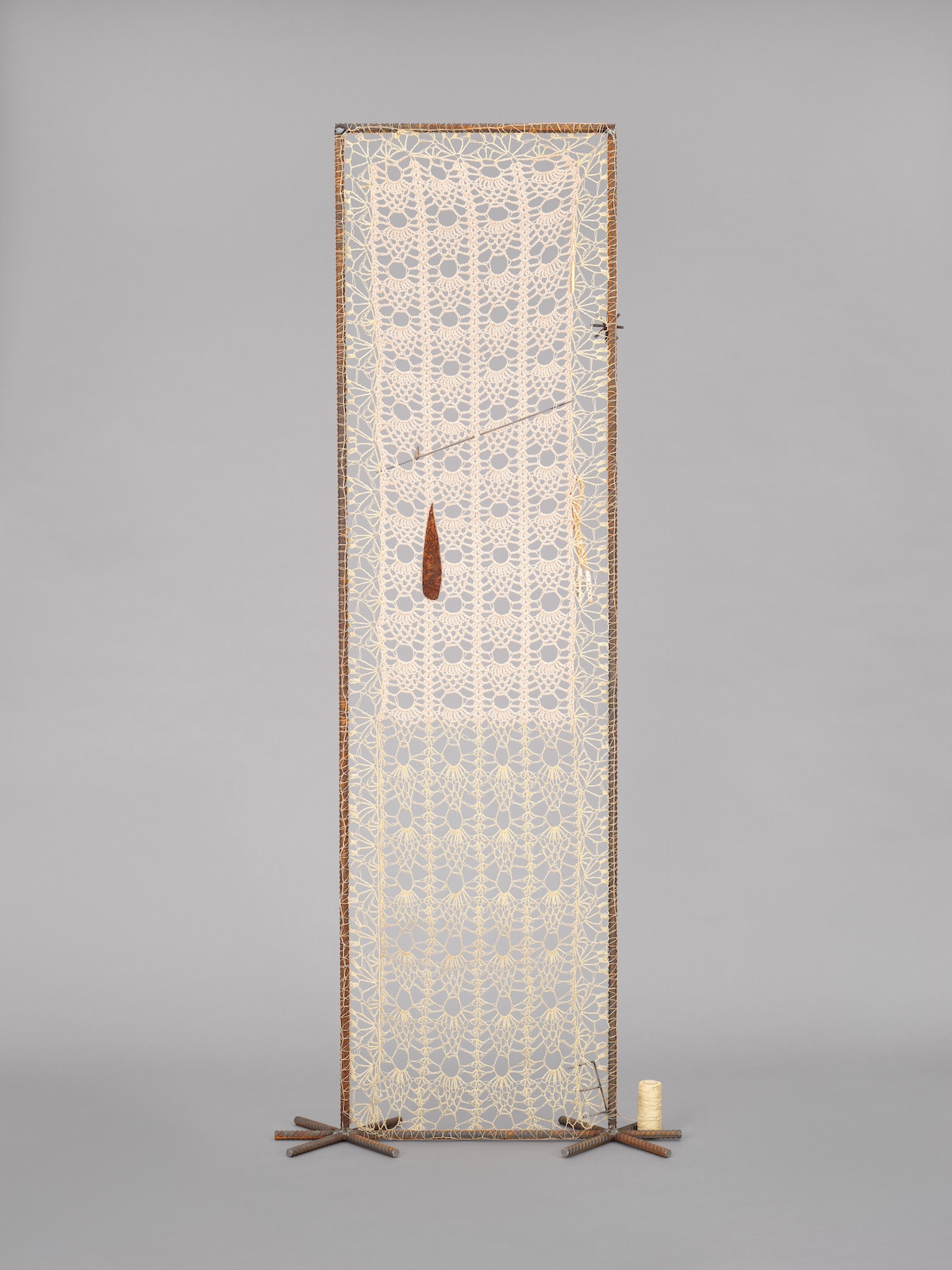

sculptures. “Teotihuacan,” named after the ancient

Mesoamerican city in the Valley of Mexico, joins mesmerizing

white crochet to a steel frame. I think about the artifacts Diego

Rivera collected there and framed in the vitrines

at Anahuacalli. Then you climb the stairs and see his planned

mural, Stalin and Mao offering peace to the peoples

of the world—Pesadilla de guerra, sueño de paz.

No, really! Stalin holds a dove. A generically ugly Uncle Sam fumes. His eyeline,

Stalin’s, extends across the mural to where Frida Kahlo

engages visitors. Probably you don’t agree. You wouldn’t say that that’s

how it went. Maybe nor would Sharon Hayes, or her crowd

of gentle older queers. Someone should ask them.

Dejygea

By Kyle Carrero Lopez

after Mavis Pusey

I looked and looked and still know not what it means.

Dejygea – Pangea, caesura, déjà voulez-vous.

Would love to know what Miss Mavis meant with that title,

yet I know that not to know for sure

is itself a gift. Reaction vid or GIF:

Kandi Burress cocks her head and cracks

you just made that up! to Porsha Williams.

And did!

Oil on canvas. There’s black and white,

and reds, greens, blues: the three primary colors in physics

(sorry to yellow)

and here we see physics sing out, the oil scene

informed by architecture informed always by physics,

structure and scaffolds and quake safety, heat and energy, and and and and!

It’s Miss Mavis’s take on the Lárge Apple’s

constant construction, constant noise,

the way its buildings shoot up and plunge down.

It’s Miss Mavis back at the Biennial after the ‘71 Biennial on Black artists

with no Black curators,

a promise undelivered, promise given a new look

by fresh eyes 53 years later:

Blackstraction redeemed!

Sitting in the crowd of a Black poet’s reading,

Hanif Abdurraqib overhears a white woman ask her neighbor

how can Black people write about flowers

at a time like this?

If I’m Black and I make a thing up and it fails to convey

the right Black thing to the right donor’s taste, did the tree make a sound?

Friends from college may remember a time, a period really,

when I fell afflicted, obsessed with saying Lazy Susan, laissez-faire.

It came forth like revelation and I couldn’t stop speaking it aloud,

or sending texts with cryptic lineation:

lazy susan

laissez-faire

Deep within my jokey, specific, idiosyncratic dome

I looked and looked and still know not what it means.