Stored

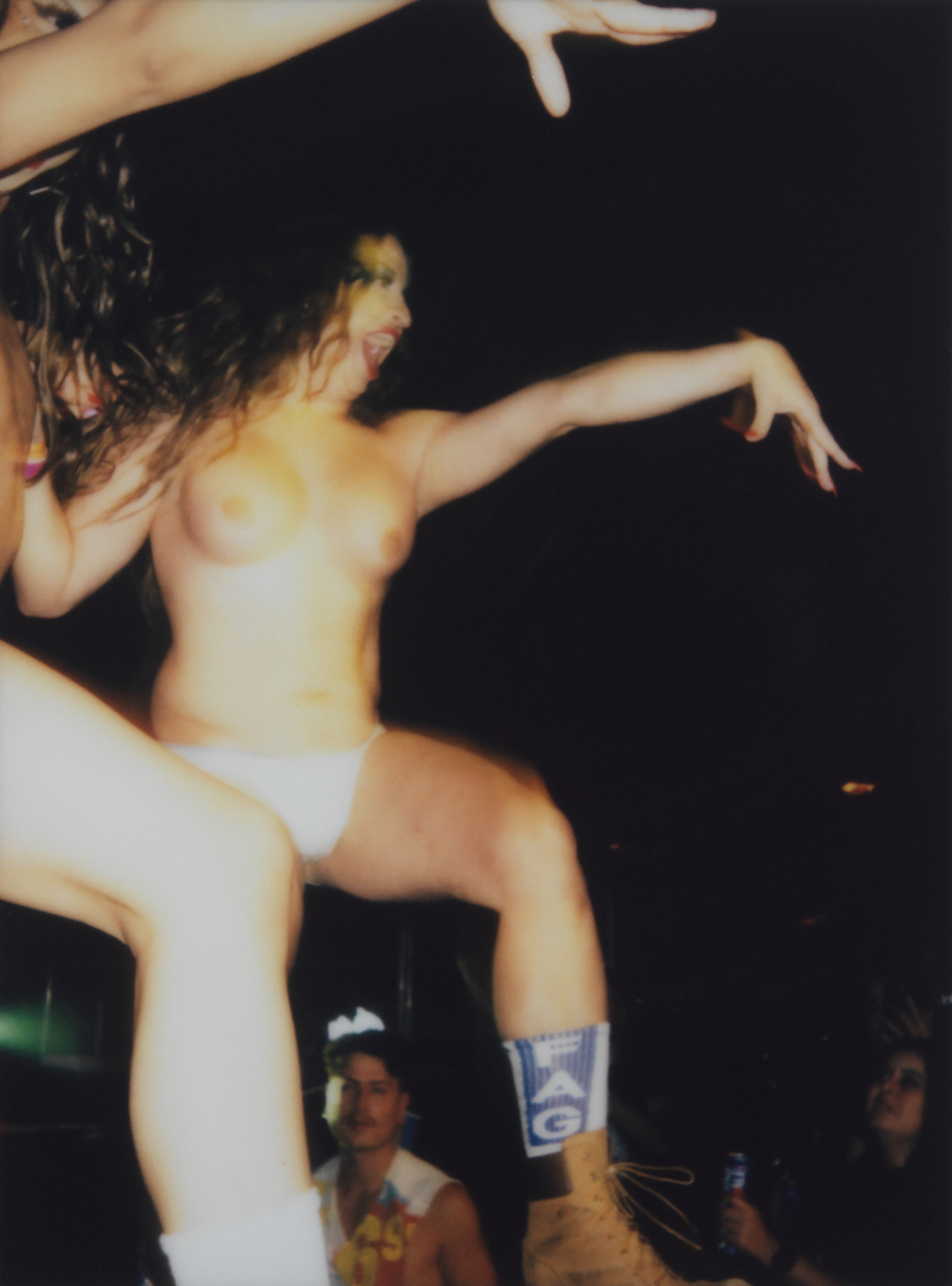

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

“There are all these vocal nuances that happen in between a phrase – the notes, the runs, the melisma that connects the emotion from one word to another,” LeRoy explains. “But that note is carrying so much information, like how we can hear Jazmine Sullivan riff without saying one word, but we know exactly what she means. What is inside of that?”

Thinking alongside renowned cultural theorist, poet, and scholar Fred Moten, LeRoy was struck by the concept of the “wordless moan.” In his essay “Black Mo’nin,” Moten references The Gospel Sound, a text by gospel producer and writer Anthony Heilbut. “The essence of the gospel style is a wordless moan,” Heilbut writes. “Always these sounds render the indescribable, implying, ‘Words can’t begin to tell you, but maybe moaning will.” “Lay Me Down In Praise,” which was exhibited as part of a collaboration between the California African American Museum and Art + Practice, drew connections between gospel’s wordless moan and the “moans” emitted by the earth amidst anthropocentric climate abuse, from the sounds of the ocean to the rustling of the trees.

Building on the foundations of his first exhibition, X’ene’s Witness sought to “build a portal” for LeRoy's community to engage in conversations about climate change – conversations that Black communities are often excluded from, despite disproportionately bearing the brunt of damage from environmental forces like air and water pollution. “I live in South Central, and almost nobody here is thinking about climate change because they’re thinking about everyday survival, how to feed their kids and how to get to work,” he says. “I'm always thinking about their access to the message.” This resolve to foreground accessibility in his work is why it was so important for LeRoy to show “Lay Me Down In Praise” in Leimert Park, a predominantly Black neighborhood in Los Angeles.

LeRoy’s own introduction to the fine art world was rather unorthodox, as was his path to becoming a working artist in his own right. During his freshman year at UC Irvine, he discovered writer and curator Kimberly Drew’s “Black Contemporary Art” Tumblr blog. “She was just sharing her interests and her knowledge, and it opened up a pathway for me, a sense of possibility,” LeRoy recounts, “to know that this world existed, and that I could situate myself in it.” He subsequently enrolled in art classes, but was disappointed to find that he was still learning more from the bloggers he found online than he was in the classroom. In 2015, he visited his first contemporary museum at the age of 20; by September of that year, he was working as a gallery attendant at the Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles; soon after, he joined the now-closed Underground Museum, where he would spend six years working in various positions and interfacing with artists including Khalil Joseph, Deana Lawson, and Henry Taylor. “But I would definitely say that music came first for me,” he says. “I was a really obsessive kid when it came to buying CDs. I still love the tangibility of it all, the research and all the liner notes.”

In 2019, LeRoy finally decided to follow his own long-held creative impulses, performing at MoMA PS1 with British composer and playwright Klein, who he credits for the final push into pursuing an artistic career of his own. “I will thank her forever for opening that possibility for me in a moment where I wasn’t sure,” he says. “She really helped me see myself.” LeRoy continued to explore his fascination with R&B music and the tradition of Black sound, and his audio work “Leave A Message” was featured in the Hammer Museum’s 2020 exhibition “Made in LA.” Alongside creating his own work, he is now the Director of Public Programs and Community Outreach at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

LeRoy’s years working for galleries and museums have left him well-equipped to deliver on his accessibility goals. “I'm thinking about the audience first,” he describes. “I'm definitely making work for me, but I want to have a conversation, I want to make sure that the work can survive in a public programming setting, and that there are different pathways to interact with it.”

“Having been on the other end of doing insurance reports and communicating with people about getting work shipped and interfacing with the public daily and seeing how things get funded and made – there’s a lot that’s at the heart of the success of an exhibition,” he continues. “I’m working with a lot of dancers and singers, and I want to help demystify what the art world is and how it works by bringing collaborators into it who have never been centered in it, and help them navigate funding resources for their work too. Hopefully that sets a standard, for how we create a moment, how we create eras, how we usher new artists in.”

X’ene’s Witness, which held two free performances on November 17th and 18th, is the culmination of a decade’s worth of collaboration and creative respect. LeRoy and his co-composer Alexander Hadyn have worked together since LeRoy was 18 years old. “We’ve learned so much from each other,” LeRoy says. “He’s my right-hand guy.” He describes performance artist and classical musician X’ene Sky, from whom the opera takes its name and its voice, as his “sister”; costume designer Corey Stokes as “one of my best friends”; creative director Franc Fernandez as a “legend”; and describes himself as a “longtime fan” of movement director Qwenga. “This piece is a combination of so much of our collective thinking and ideas,” LeRoy says. “I’ve never done anything like this before – my career as an artist is very young, and it’s a big leap. There’s a lot of surrendering taking place right now. I brought everybody into the fold because I have so much faith in what they do as individuals.”

Michella's "Unmade beds" is also currently on view at Shoot the Lobster, New York, until November 25th.

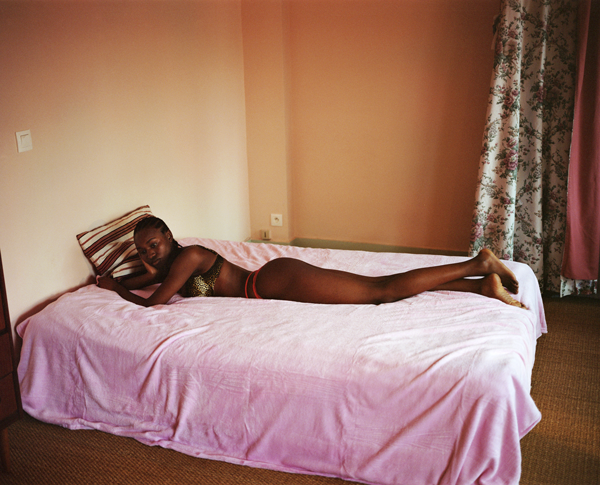

Congratulations on your first printed publication. This has been a work-in-progress for the past decade, how have you matured, as a person and a professional, since starting? What have you learned?

Thank you. Yes, the oldest picture in the book was taken when I was in art school in 2012. My friend had just gotten pregnant and I was playing around with my camera that I bought online. I went around to her house and took her portrait with her boyfriend at the time. I was really nervous about what I was doing back then, but I didn’t let that stop me. I think that’s what this journey has taught me the most. That just because you can’t put something into words when you start out, it doesn’t mean it's not valuable or that you’re not on the right path.

You start somewhere and by trying and making mistakes, it takes you somewhere else. You have a lot of bad days as well. It's hard when everyone else goes to school and gets good money jobs, and you still don't really know what you're doing, and on top of that no one hires you. It's like you’re this wolf who has left the pack you were born into.

I don't come from any creative family so I had to find my own way and try it out for myself. In the beginning I would have so much sweat anxiety on my forehead even when I photographed a friend, because I was sure they thought I was crazy for showing up at their house and asking if I could take their portrait. I had a heart but I let that lead me forward. I was curious and I didn’t let it distract me when people tried to turn my passion for photography into something indecent or asked stupid questions like how are you going to make a living out of it.

I started by taking painting and drawing classes and that introduced me to photography and cinema. One day an older friend of mine who was a photographer handed me a photo book by Diane Arbus. I didn't know her. I was completely enchanted. Her pictures spoke to my soul. From there I started photographing every day. I discovered Nan Goldin. William Eggleston. I could see that all these photographers had something in common. They photographed their friends and people close to them. I had done that all my life, but I had always felt that I was not entitled to it. In their pictures and books I found a place where I belonged. I started to trust what I was doing. I feel that when you start out, it’s like learning a new language or trying to teach other people your language. It takes time. To me photography is about time.

When I photograph today, I'm much more relaxed and really feel like I've come home, especially because people now welcome my photography much more and show joy in seeing them. For a long time it felt quite lonely to photograph and somehow it’s now suddenly the complete opposite. It feels like I've found a big family.

The photographs have this sense of stillness, but aren't exactly quiet. What dialogue are they prompting?

I believe that the pictures show life and close moments in everyday life and that all those lives and moments are meaningful. That all feelings are welcome. My pictures are also self-portraits. I have a lot inside that wants to come out. I think that’s what speaks most vividly through my portraits. But there is also a collective cry. Many in my generation of friends are angry and frustrated with the world. We want a world that is led by love and that there is room for everyone. And that the vulnerable are looked after and that it is a power.

I feel like I grew up in a world where my parents taught me that showing emotion was a sort of weakness. I feel that our generation and the next ones are in total revolt with that. We are reteaching each other to seek love and to break all the barriers within ourselves that we have built against it.

Love Me Again by Michella Bredahl is published by Loose Joints.© Michella Bredahl 2023 courtesy Loose Joints

The work is titled Love Me Again, could you tell us when and where that love was first lost?

The title is very attached to my mother. That's photography for me in general. The love was first lost with her. My mother was the first to give me a camera when I was 7 years old. The first pictures I ever took were with her camera and of her. My mother was a haunted soul. The camera became a tool for me in all the chaos I grew up around. I think my mother used the camera to create a world she could endure being in. It was a dark time. We lost touch for many years, almost ten years. Everything I create, I create from that place and memories I share with her, but I feel like I'm creating something beautiful out of that dark place.

Perhaps you could say that I visit the dark places and step out of them again with light. The title refers to her love and desire to find each other again, despite all the bad things that happened. It also touches on all the different aspects that love can arise between us and those that I love in the book, and hope that the love is mutual.

You’ve also mentioned how dangerous a pair of eyes can be. When is the gaze a weapon? How does one reclaim it?

For me, the gaze is always somewhat of a risk, because you never know who is looking and what eyes they are looking with. I have modeled since I was 14 years old. I was very young. I feel adults capitalized on my beauty and vulnerability. They objectified me. I never saw the images of me before they were in a magazine. That disconnection is how the gaze can become a weapon.

The reclaiming you need to be human. You need to speak and connect with the people you photograph. This book was made in collaboration with many people with whom I feel I share the same thoughts and feelings about the world. I think the most important thing in my work is all the time I spend with the people I photograph and many of them are people who are very close in my life. They don't see my gaze as something dangerous, on the contrary, I feel they see it as a joint struggle to create and express ourselves as who we were born to be. But I don’t want to come across as someone who figured it all out. I make mistakes and that's the way to growth. You take responsibility when someone feels unheard or misseen.

Love Me Again by Michella Bredahl is published by Loose Joints.© Michella Bredahl 2023 courtesy Loose Joints

“Reclaiming an empowering space for this energy to express itself entirely for its own needs and reasons, without shame." What did you mean by this?

I think shame is something everyone carries in different sizes. When we enter the world we depend on the adults in our lives to love and accept us and for them to look after us. Most people I know struggle with shame because of their parents or the adults they had around them as a child. An encounter as a child with a bad person can set off shame, a feeling that one is inherently wrong; I have struggled with a lot of shame because of my mother.

Shame for me was something that arose in my childhood home. I re-enter the domestic sphere to rebel against this feeling and to replace it with something beautiful and empowering through the camera. Shame can be described by a long chain of emotions, such as wrongness, inadequacy, embarrassment and lack of value as a human being. When you experience shame, the focus is primarily on the inside, and you may get the feeling of shrinking or that your body is distorted. You feel that you’re an object of another person's negative gaze. And even if we don't know what other people think of us, and if they even see the faults we think they see, shame grows out of the uncertainty and the notion of other people's possible negative assessment.

In my work when I photograph, for me it is about creating a transparent space. I want the person I photograph to feel beautiful, with everything they contain. I also look at myself when I photograph. I tell that little girl that she is not wrong. Photography for me is a way to look at all these broken feelings and to talk about it together. It’s a desire in my work, to create a space where those I photograph do not feel wrong through my gaze.

For you, what exactly is 'the feminine', the female spirit?

It’s beauty. It’s venus. It’s the moon. It’s both soft and it’s rooted. My joy for femininity is something that comes out of my upbringing. I grew up with my mother and younger sister. My mother was incredibly feminine. She loved makeup, sexy underwear, clothes, and she set her hair every day. She moved elegantly around the kitchen, even when she was cooking. My mother also had many gay friends. The way everyone held a cigarette was a scene. I was very fascinated by this way of being. The way they laughed. Danced around our apartment until the morning. High heels they all walked around in. I always felt most comfortable in that energy. My home was full of friends from different backgrounds and different shades of femininity. My best friend's parents were from the old Yugoslavia and my other friend's mother was from Poland. We got ready in my room. Just like my mother did with her friends. We put on makeup, did each other's hair.

When I watch films with Zoe Lund, it reminds me of my mother. My mother had this insane feminine attraction. My own relationship with femininity has been a long journey. I worked as a model where I felt that people capitalized on my femininity and fragility. Therefore, for many years after I stopped being a model, I downplayed my femininity. Since I moved to Paris, I have gone through a transformation. Here I have allowed myself to explore my femininity. It's many things. I think it is very individual what it is for each person. For me it is an essence. Femininity doesn’t only belong to her, it’s an energy that everyone can carry.

Love Me Again by Michella Bredahl is published by Loose Joints.© Michella Bredahl 2023 courtesy Loose Joints

To what extent do you consider ourselves a reflection of others? Is there any such thing as a core identity or are we rather fragments of our surroundings?

Well, I don’t think that there is a core identity per say. I think people are much more alike on the emotional level then we walk around expressing ourselves. Other artists have expressed that there is this one love. I resonate with that. We are conditioned by society. I think we have been assigned different tools to express ourselves, for example, when it comes to love. I think most people basically just want to be loved, and so we have learned different ways of showing it or not showing it at all, depending on our lives.

The photographs invite us to put our guard down, talk to ourselves when greeting her gaze. What do you wish for us to reflect upon once we put the book down?

I hope that the book can remind us to look after each other and show love and compassion every day with one another.

Looking ahead, is this narrative a closed chapter or something you’d like to continue expanding upon throughout your practice?

When I photograph, I don't have a narrative hanging over my head. It is something that my publishers have also helped to create. I'm sure if we looked through my archive we could choose many different narratives to build a book around.

I intend to continue taking photographs, and especially of those that are in the book. This is just the beginning for me. Again as I said early on — you start somewhere and it takes you somewhere else. I look forward to seeing where this book takes me. I have already started a film project that I will shoot for next year. I hope that I can find the right publisher to publish my book about my mother. For me, it's mostly about doing it and not quitting. And to learn from all your discoveries, mistakes, to develop and grow. That’s a part of what living is.

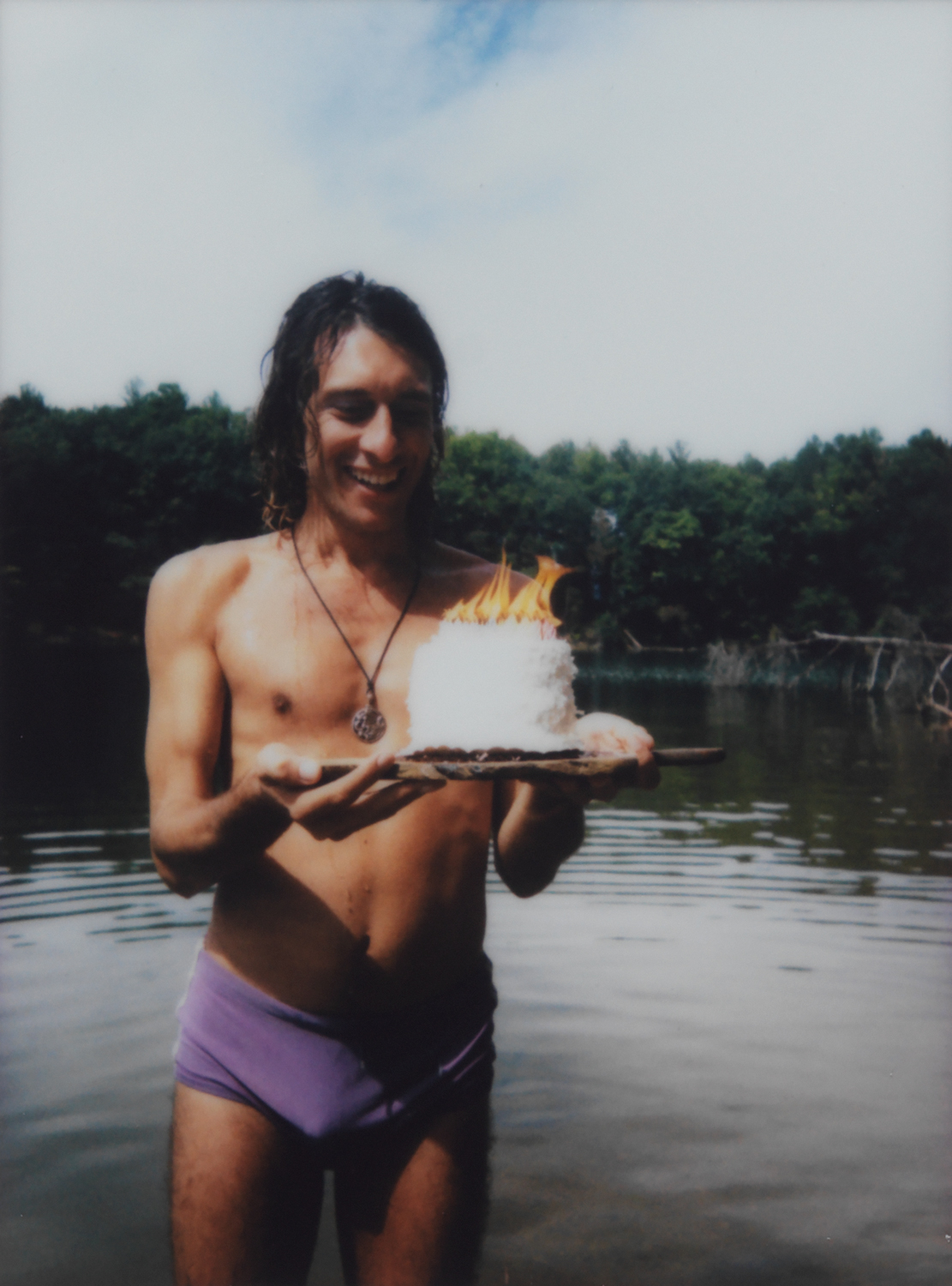

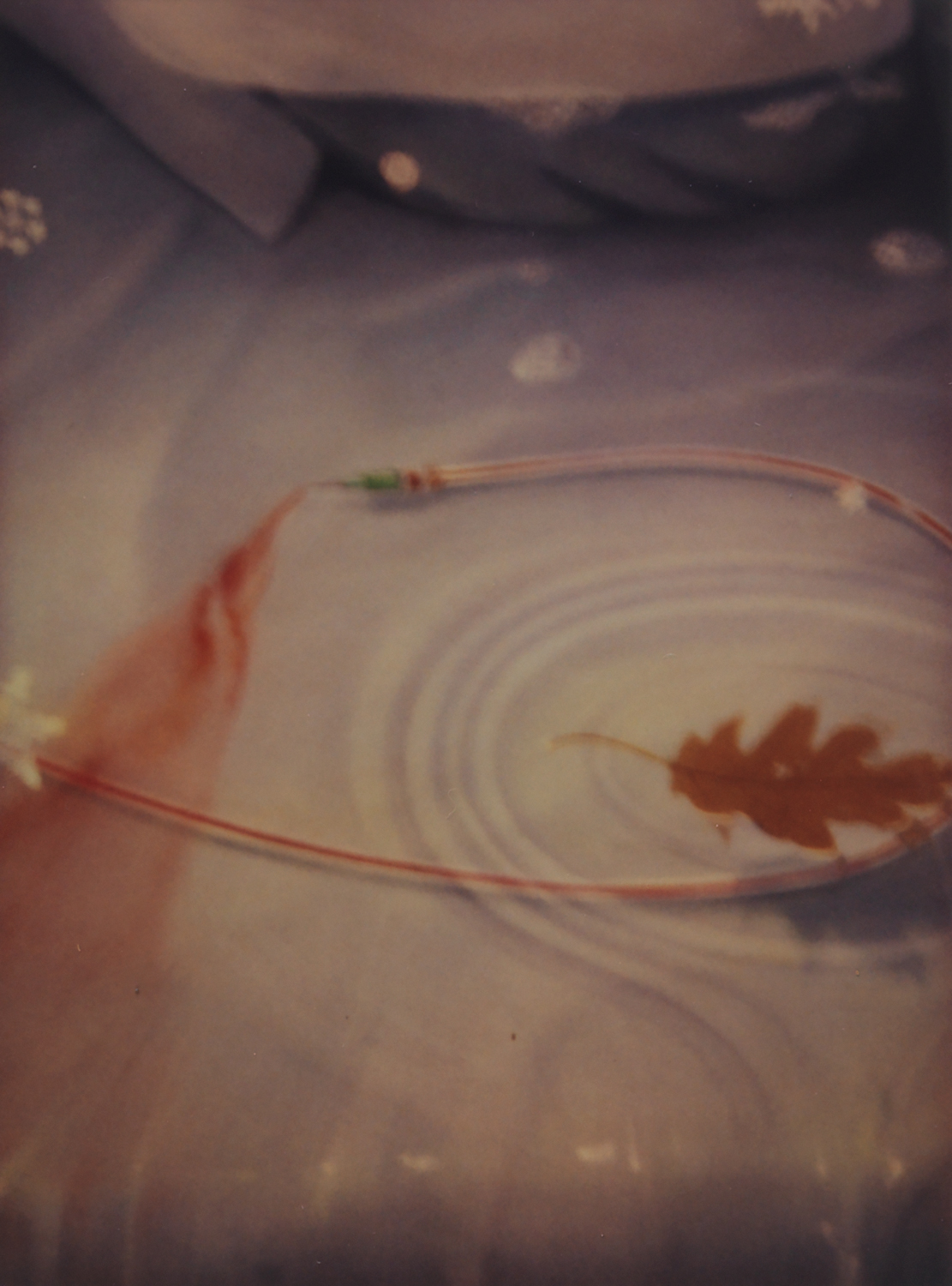

Earnest weaves together images of artwork from Renaissance paintings to contemporary sculpture with moments from his own life, drawn to what he calls the more “permeable” images over “perfect” ones. The photos serve as entry points for the reader — who perhaps may be described more aptly as a witness — to investigate their own boundary that claims to separate art and life.

The written tableaus that accompany his images are made up of laconic observations and retellings, unceremonious but nonetheless suffused with a tenderness that is little too self-aware to be called nostalgia. Earnest transmutes his critic's scholarly logic and precision to navigate the jagged and precarious terrain of self-examination. That self-awareness permeates the work, perhaps inevitably — after all, it is a meta-reflection on these years of Earnest’s life, a retrospection on retrospections, an analysis of the memory of memory.

In one photo, a bouquet of flowers is placed on the grave of the aforementioned philosopher Simone Weil. In another, a lover lies naked on a bed, shot from above, a circle of post-coital dampness still visible on the sheets beside him. In Valid Until Sunset, love and loss, art and sex, and life and death rest shoulder to shoulder, arm in arm, blurring the distinctions between one another, between the past and the present, and between Earnest and ourselves.

The photos “address you in the second person,” he writes, and so does he, narrating in the present tense. Of course, these moments are from the past, not the present, and they are his, not ours – but the central contemplation is a universal one. Valid Until Sunset is a meditation not only on how we see our lives, but how we ‘write’ them through documentation and storymaking, and how we read them, and read them again, and again, and again.

Jarrett Earnest is an artist, writer and curator living in New York City. His books include What It Means To Write About Art: Interviews with Art Critics (David Zwirner Books, 2018), The Young and Evil: Queer Modernism in New York 1930-1955 (David Zwirner Books 2020), Painting is a Supreme Fiction: Jesse Murry Writings, 1980-1993 (Soberscove, 2021), and Devotion: Today's Future is Tomorrow's Archive (Public, 2022). His writing has appeared regularly in the New York Review of Books, among many exhibition catalogs and other publications.

Valid Until Sunset is available for purchase from MATTE Editions.