The View From Afar

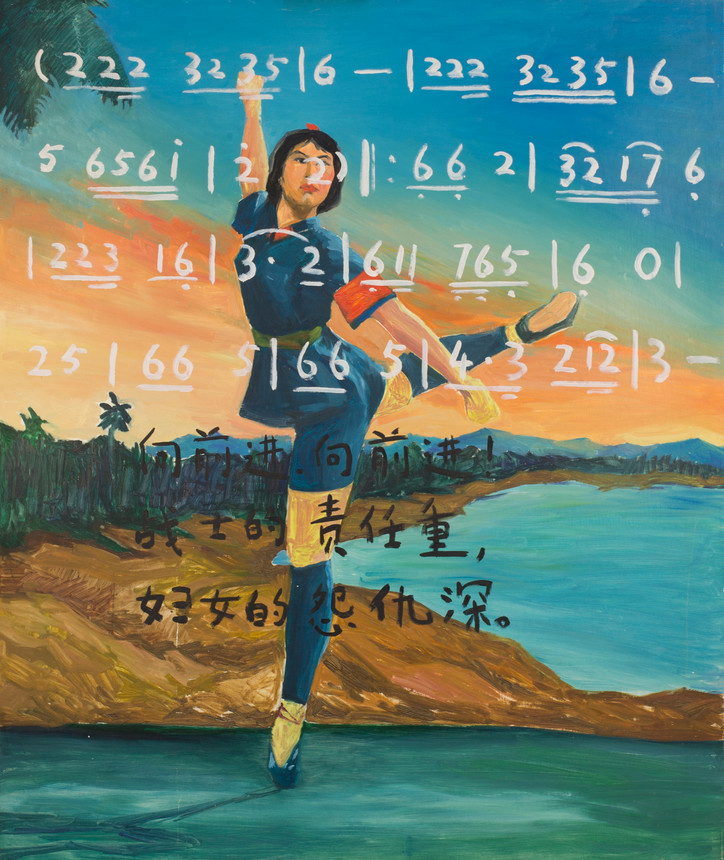

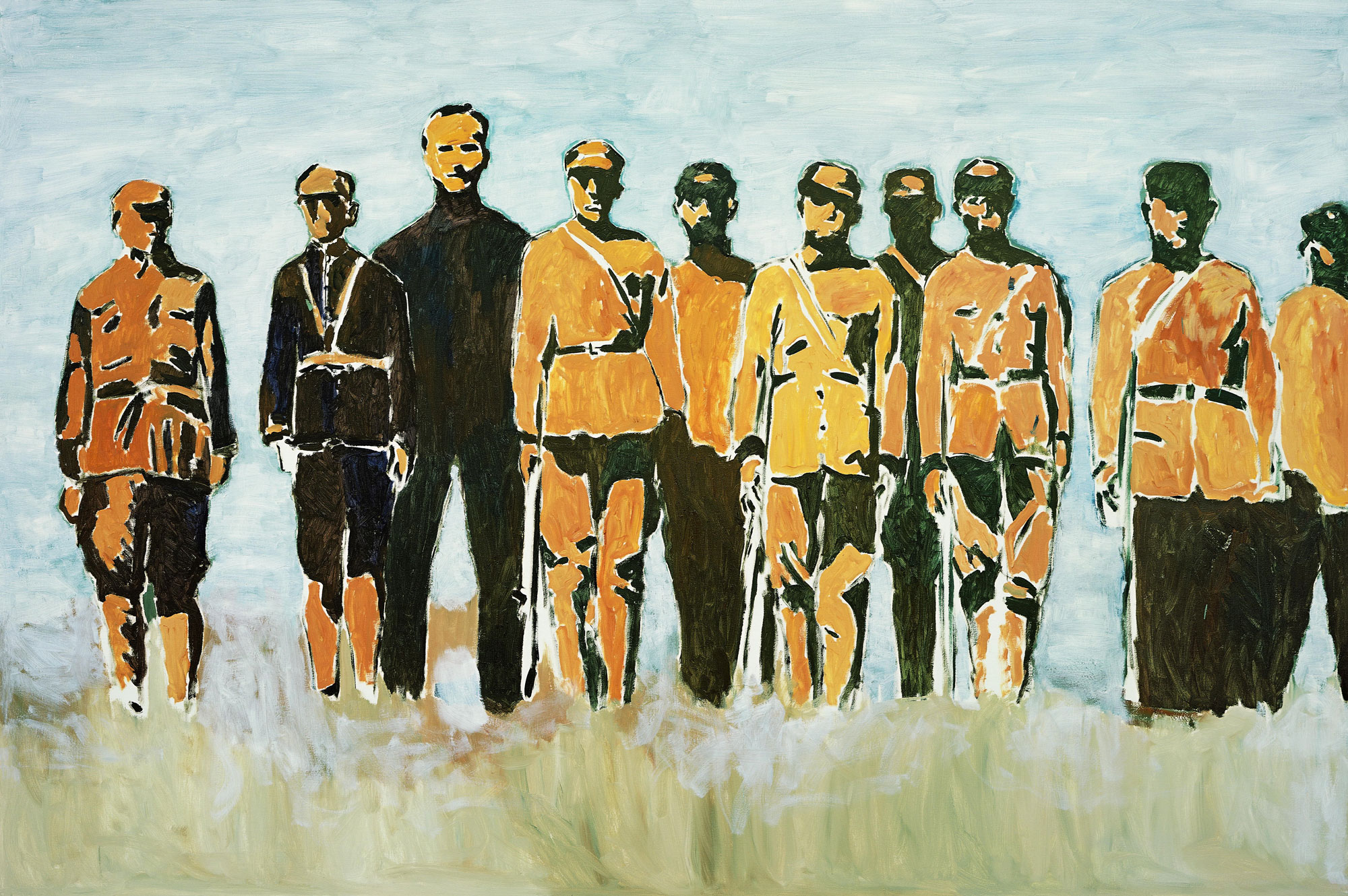

Gang was the youngest member of the Stars Group, an avant-garde art movement in China that began in about the early ‘70s. An article from Artsy explains that the work of the Stars Group diverged from the socialist realist style that was promoted under the communist regime and that it valued “individualism and freedom of expression” at a time when it was dangerous to do so. But the Stars Group continued to make their work, protested, and found ways to display their art, including in their own apartments (hence this exhibit’s setting).

The group disbanded in the ‘80s when many of its members left China, including Gang. The artist moved West, to live and study art in the Netherlands and New York, then he returned to Beijing in 2006. And now he lives and works there and in Taipei, Taiwan. Gang’s work examines China both up close and from a distance. And the paintings presented in this exhibit involve looking back on China’s past and his memories of the Cultural Revolution.

Although the art scene has changed, both in the East and West, Gang finds that in many ways, things remain the same. Read the interview with the artist below.

Tell me a bit about your work showing at PAMM.

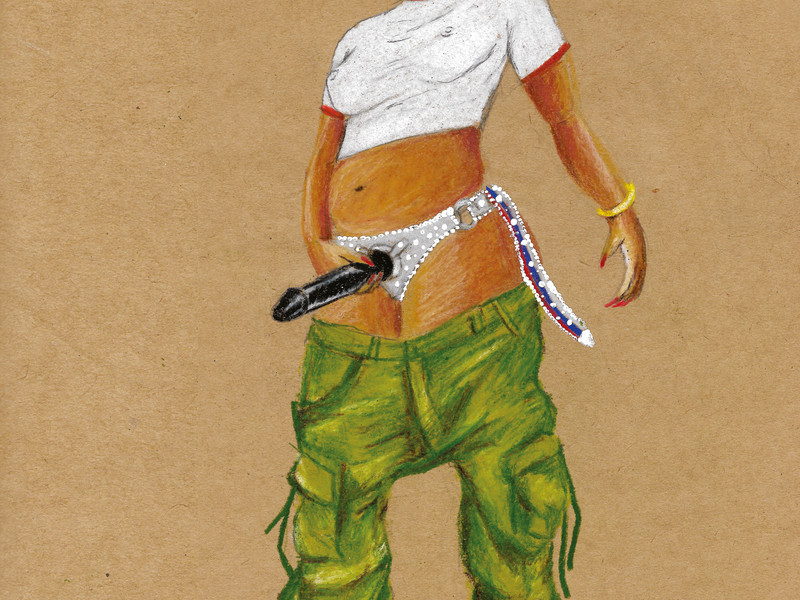

This is a survey of my work from about the early 2000s until now. It’s a figurative representation and realism, but also a criticism of realism. It’s a satiric approach to some iconic paintings.

A lot of people refer to you as “an outsider” of both Eastern and Western cultures. What have been some of the advantages for your perspective as an artist having lived in both cultures?

It wasn’t really an advantage, the idea of me being an insider or me being an outsider, it all depends on how they wanna play it. I was always an insider, I was an insider in both China and New York because my practice was part of the new stream art practice. In China though, from time to time, they choose not to include me in their practice. But a lot of Chinese artists have briefly lived abroad or visited.

So is that where the idea of being an outsider came from?

Yeah, exactly. It’s a very typical Chinese game. Even though they include you as an insider, they know you are challenging them, they know you are a threat to them. So they’d rather have you take on a different identity. Like now in China, I’m included in art history books and I’m a founding member of the Stars Group and China avant-garde, there are still certain people they like to promote instead. There’s kind of a circle, like the art mafiosos.

So people were wanting to define your work in terms of who you were as a person or an artist?

Well in China there’s no way to read about my art. Some good artists understand what I’m trying to do. But most people don’t now. Most Chinese art critics are stupid and they always try to define certain art in relation to European art. Now there is a big deal of them being sort of pseudo-intellectual and it’s kind of…volunteer colonialism. They don’t understand how to challenge art history, they’re trying to place more value on European art history than they understand. That’s the problem, that’s the irony. It’s the Chinese and contemporary Chinese art world practicing on a very shallow basis. And the education, I taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, it’s just horrible. I think the Chinese art practice is so hypocritical, they want to please the Western territorials and the local powers and authoritarians, it’s very mixed. I paid dearly for my freedom.

What do you mean by that?

Well because they always try to find a way to persecute me and push me out. My art is really not about me being a painter, it’s really about my performance of being an artist [laughs].

What would you say about the American side?

When I came to New York in the ‘80s, there was a super elite or white art practice that was very hard to get into. I don’t think the New York art world pushed me out, it’s just that I haven’t really gotten in yet. I was an immigrant, so I’ve always had the outsider persona attached to me.

It’s still something that you’re trying to get into is what you’re saying?

I was, but now I don’t try anymore. I’m out again. In the beginning I tried. But trying without an understanding is a different kind of trying.

Memory, looking back and depicting what you remember from growing up in China, has been an important part of your work. Discuss the use of memory in your work and how it continues to play a role in your more recent works.

I always think about images from when I was little. And I like to read historical books with photos in it. I always try association of images: the old and new, memory and imagination, classic and current images.

Was the use of memory in your art different once you returned to China?

I’ll put it in more of a philosophical way, memories can be concurrent with something you have to imagine and something that actually exists. In other words, it could be abstract memory and it could be realistic memory. That’s what I’m trying to work with. I actually have no relationship with some of the images, but they have a relationship to me in the most abstract way through metaphorical references.

How do you see artists responding to what’s going on now both in the East and West and how do you think it’s different from the way that you responded when you were a young artist?

Younger artists are much more shrewd in their art practice, more angled. I think everyone’s more interested in commercial success. It’s very critical because art is a business. It’s a very important, very big business. I think now Chinese, American, European artists, all of the successful ones, are also very good in business.

Do you think that’s one of the things that is defining this younger generation of artists coming up, is that there’s more of a focus on commercial success?

Yeah, of course. They’re more explicit than the older artists. The 80-year-olds, they think about art more and the younger ones they’re very smart, shrewd, well-educated and well-informed.

Is that because they have more tools at their disposal to help them navigate the business side or art?

Exactly.

Why do you think that is?

I think it’s always been like this. I think Picasso’s the best businessman of his time. Picasso’s not about art, he’s about how to make a business out of art. He is the ultimate inspiration of the art business.

In an interview with the exhibition’s guest curator, he said that we will begin to see more multi-cultural art or art that can’t be defined as or influenced by just one thing. Do you agree?

Yes, I’m sure. I think artists always end up dealing with their own identities. So multi-ism, multi-racialism, I don’t know what the future holds, but sure enough it’s very entertaining.

Do you think more artists are defining themselves as being multiple things at once?

Art is always about an identity crisis.

“Zhao Gang: History Painting” will be on view at the Pérez Art Museum Miami until January 5, 2020