After MoMA, Wolfgang Tillmans

Tillmans takes pictures of his food. I noticed this when we sat down in David Zwirner’s labyrinthian back office for our interview. In front of us was a delectable spread of glistening pastries and tarts. As I took in the scene, I realized Tillmans had quickly taken out his phone and snapped two photos: one of the sweets and one of me uncapping a pen. Later, we discussed this habit and he revealed that he, like all of us, documents his most delicious meals.

This was both obvious and revealing.

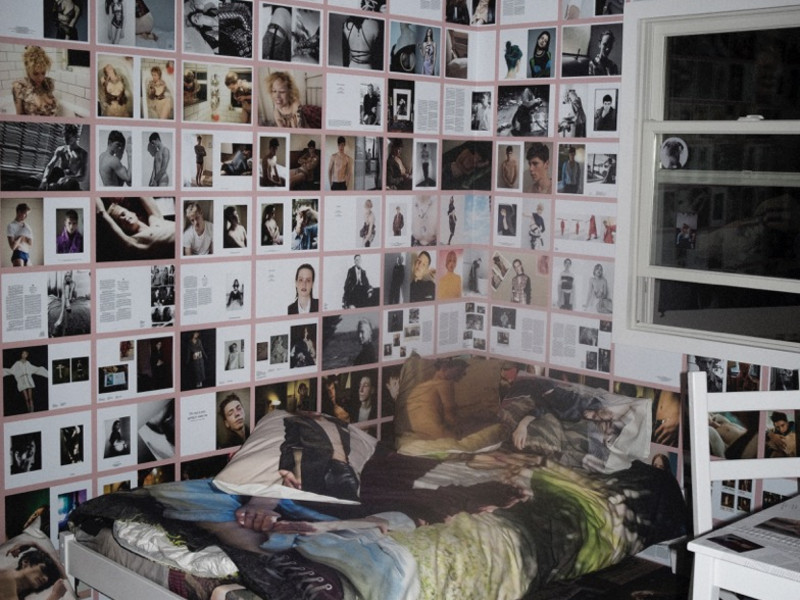

In a world ubiquitously filled with cameras, fine art photography is plagued by questions of its relevance. For some artists, this has necessitated a push to make more elaborate and self-critical work. Tillmans has spent his career doing just the opposite, making images of the quotidian. One of his veteran subjects is rumpled clothing––which he has photographed slouched over banisters and atop plain floors. Rather than a style, he has a sensibility. For Tillmans, the world is a curious place, and intrigue can strike him at any moment. For him, the distinction between the diaristic and the artistic is always clear; he can tell when something will be interesting. Yet, as all of us do, he also maintains a record of his life with his smartphone camera.

He is not a documentarian: he is an artist, and the distinction is critical. The difference between one of his still life photographs and an image he takes to remember a meal is the difference between a work of contemporary fine art photography and a symptom of an image saturated culture. During our interview, he said that “to be genuinely interested in a different perspective is sincere.” His work boldly asserts that earnestness of art making is the distinguishing characteristic between art photography and meaningless recording. If we agree with him, intentional image making may still have a purpose in our society.

He once said that, “In photography I like to assume exactly the unprivileged position, the position everybody can take, who chooses to sit at an airplane window or chooses to climb a tower.” In our conversation, we discuss the aftermath of his recent MoMA show, where his unprivileged perspective was codified as a defining contribution to contemporary art.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Where did you get your shirt from?

Wolfgang Tillmans: This is an artwork by Juan Pablo Echeverri, the Colombian artist with whom I became close friends and who passed away last year. It's the typeface of Metallica, which is this macho, masc band, and then the word Maricona, which is an exaggeration of gay: “hyper gay”.

I was reading in an interview that you did with [Slavoj] Zizek where he was talking about his resistance to the one-line autobiography, and he gave his parody of one. I was curious, over the years, has yours changed? And do you have one that you use when asked? Who is Wolfgang Tillmans?

I don't find I have to give a one-line narrative other than in a taxi or at a dinner where I end up randomly seated next to somebody who has no idea who I am.

In those cases, questions only arise once I have made it clear that I make art, because then, they want to size me up. Most of the time, they quickly tell me about an artist they know, often someone in their family. People are not as interested in artists as they are in telling you about an artist they know.

But my answer to your question hasn't really changed. I'm an artist primarily working with photography and installation––sound and video––based in Berlin and London. Since 2011, I have spent most of my time in Berlin, but maintain a connection to London, where I've been for 33 years now. I also lived in New York in the mid-90s, and after having taken some time away in the 2000s, I've been feeling really close and connected to New York again. I have spent summers on Fire Island for the past decade or so. The New York audience has been an incredible sparring partner for me and the museum show [his MoMA retrospective] last year was a years-long engagement with the MoMA team, the gallery [David Zwirner], and so many friends and amazing intellectuals.

Congratulations on the MoMA show. You have talked about this exhibition as a step in a different direction, or at least a fresh breath of air for your work. I'm curious to hear what that new direction is.

I haven't announced it like that. For me, it's more the obvious question of what to do after a retrospective of 35 years in one of the most prestigious museums, where I was given the most generous exhibition space. I was, and am, totally happy about everything that I experienced and that I was able to show. Now I am asking the predictable question, what do you do after it?

In December, I went into editing mode and looked through three years of photography and work, which took three or four months. I critically considered what photography meant to me and what I could do for it. Oftentimes, I work on photographs a year after I have taken them.

Nothing in “Fold Me” has been seen before, even though they sometimes date older. At the end of this excruciating period––looking at all the pictures, including the bad ones, is terrible and despairing at times––there was new work that is still fully engaged with the world. It is also in continuity with what I've done before. I like that idea. That the new is not a break from the past, but is somehow always an ongoing conversation.

You certainly have the status of someone who captured the 90's. What is the connective tissue between the work that people will see in “Fold me”?

The strength of the reception of the 1990s work at MoMA caught me by surprise. This was a rare example of an exhibition I strictly organized chronologically, so people were hit with an energy in the first three rooms.

It is good and all right that it made that connection with people. I made that work in my 20s, which is a unique time in life, a peak of firsts with constant experiences and reactions. As an artist, you are responding with an energy that is hard to maintain later. Fortunately, I still have that curiosity for people, places and objects. I have maintained an interest in seeing things and people with an open heart and curiosity, and still have a desire to represent them in a way that doesn't bend them into something they are not; this is the naturalism I have developed as my language.

I think it's a nice sentiment. I think remaining fresh to the world is a core tenet of a life well lived. It is a beautiful idea to be young forever in that way. Was it emotionally difficult, knowing you summited one of the greatest peaks of your career? I don't know if it's credibility, you said prestige...

Prestige is really not what I would like to say that I’m after. Prestige is an expensive watch or something [laughs]. No, no, a prestigious award is actually a good thing. It is hard for an artist to arrive because our general driving attitude is achievement oriented. You want to break down barriers. You want to open up doors and you want to get into a place or into a position.

23 years ago, in 2000, a close friend of mine said after I won the Turner Prize, “you've done it, you can stop. You've done it, and it's done." And I was like, "What are you talking about?" MoMA holds a certain uniqueness, but you cannot make an illusion for yourself that there is another climb from there."

Sorry, I just realized that I'm just getting a little lost in too much of this career introspection and self-assessment. But your question was much simpler, was it emotionally… what was it?

Difficult, but perhaps difficult is a bit course.

There are two things. One thing I still notice to this day. One could quite literally call it trauma, although a positive trauma. Trauma in medicine means a heavy impact. It was undeniably a heavy impact to my whole system that has had immense aftershocks. I feel very grateful that I came out of it in one piece and happy. I didn't fall out with anybody or anything, it was all good.

The other thing was a feeling I experienced on the third and fourth day of January this past year. The exhibition had ended on the second, and I woke up happy. I wasn't sad that it was over, but I was happy that I didn’t have to think about it anymore [laughs]. It had been hovering around me for years, and was finally just done. Then I got excited about the AGO in Toronto which turned out to be a really beautiful, completely different installation of the same material. And now I'm headed to San Francisco at the end of October to prepare for an opening of the exhibition on the tenth of November.

I was thinking about essay films while viewing “Fold Me”. There is something cinematic about your work. But instead of temporally, ideas are organized across space. Unlike in film, I have my own agency as a viewer to chart a course through your exhibition. How much ambiguity do you allow for in your galleries? How do you balance the tension between your aesthetic vision and a viewer’s interpretive agency?

That is a good question considering what I've been thinking about the past couple of weeks. There is so much interesting information I could give about each photograph, and on the other hand, it seems hard to give it in equal amounts about every work. How should I dose it, and how should I dispense it? You could make an audio gallery guide. And everybody would walk around with their headphones. And you could write three sentences or have a limit of 200 words…

[Wolfgang takes out his phone and moves to the window to snap a photo of the neighboring Frank Gehry designed building. Throughout our conversation, the light has changed dramatically, and the building’s windows are an incredibly dynamic surface]

Sorry I can't resist; I have just been noting the light this whole time…

And I can't resist photographing you photographing this.

No, please. One thing I don't like is being photographed photographing. They look the same. All photographers look the same taking pictures. It's like this bent over, hunter-ish, elongated pose. I find it strange and aggressive, and it doesn't tell you anything about the truth that the photograph might reveal.

It's deleted.

I mean, for your own memory, keep it, but please don't post it.

I guess that's quite indicative of how I am wired. I just couldn't resist my interest in what I saw just there. But, back to the topic at hand. Would it be interesting for me to tell you about this Frank Gehry building, and the architecture it is reflecting from across the street, and maybe a little bit about windows? Do you really need to read about windows?

For “Fold Me”, I decided that I couldn’t give an explanation for every picture. On the other hand, during my press walkthrough, I did provide some opening windows for people to make connections across the works. But in contemporary art, overt self-explanation is heavily frowned upon; it's considered “not cool”. And for a good reason. You are already in front of the art. You are “in” the art when visiting a gallery, concert, or cinema, and you have ideally made yourself 100% open to the artist's output. To then get an audio guide or a handout from the artist is perhaps excessive and would prevent you from feeling your own agency. I like to have the agency to discover myself in other people's work.

I have found that I haven't been overcome by a desire to explain too much. I trust that when the work is good, it will speak to 4 or 8 percent of the viewers. And then another piece hopefully speaks to 7% of another part of the audience. It's anathema to me to expect that everything has to communicate at the same level, intensity and intelligibility. From an early age, I liked when pop lyrics, New Order lyrics for example, didn't make much real, tangible sense.

Your work seems fixated on visual mistakes people make in seeing. Something looks like another thing, or recalls another reference. Sometimes, the names seem to reveal this, as with “Lunar Landscape”. I was taken by this work, but I don't think I would have made the same analogy without your title. Yet, you don't include the titles next to your work. Do you expect that people make the same analogies as you, or is it enough that they carry similar feelings in looking at your images?

The “Lunar Landscape” title, for example, is not suggesting it could look like the moon's surface, but is just directing the attention to an element of the landscape, because the illumination is lunar. The audience surprised me, because they completely assumed that it was a black and white photograph. They can't imagine it is a color photograph. The light of a high full moon is as white as sunlight, and the water has no color, so it is literally black and white. To say in brackets “color photograph" would be an over explanation. I never pointed out that 10% of my images until 2010 are black and white, including many of the famous ones, “Anders pulling a splinter” and “Deer Hirsch”. However, they're always tinted and photographed with an understanding of color photography and are printed on color paper.

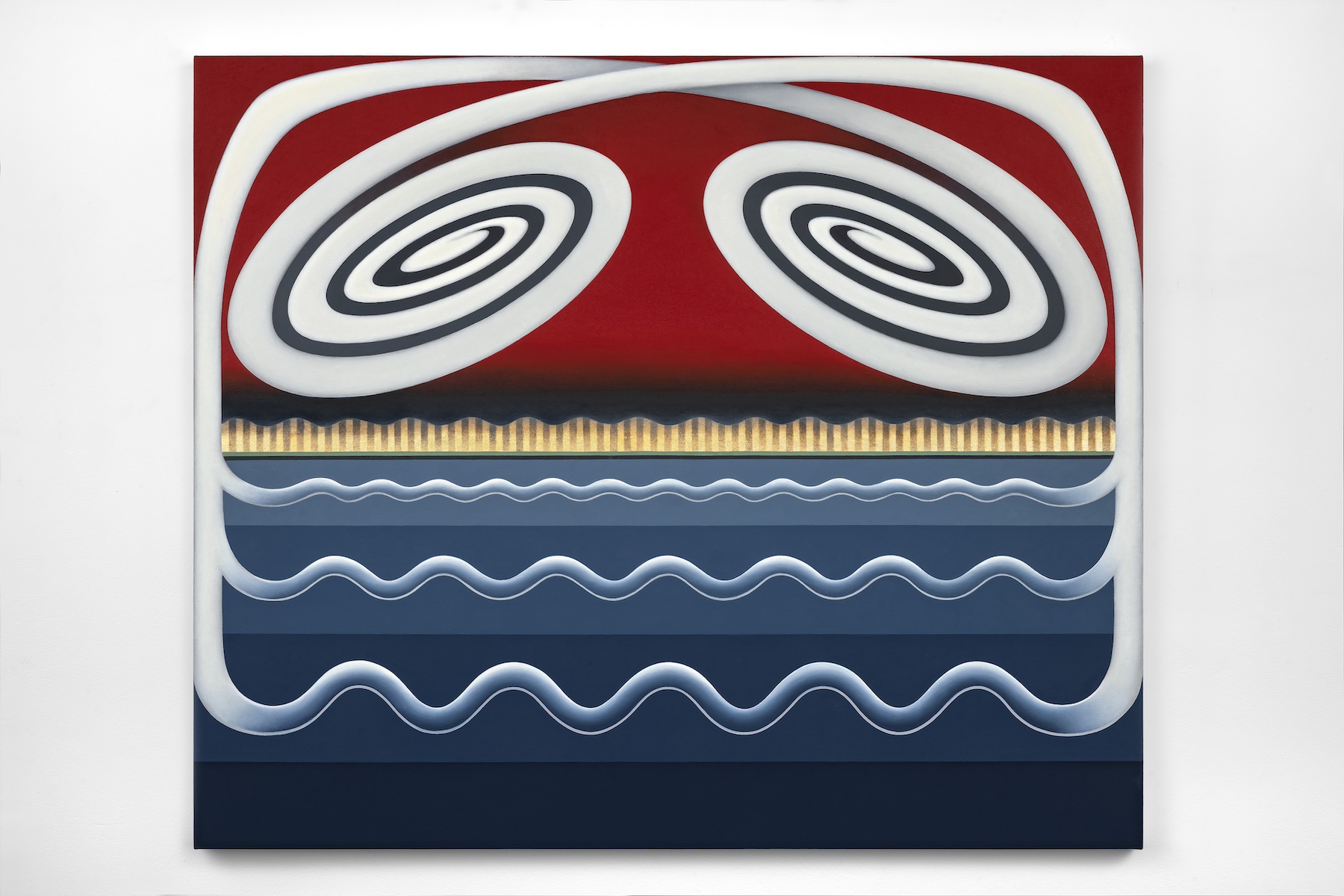

You spoke about “Rain Splashed Painted Life” as conveying this feeling of palm trees against a sunset. I don't know if I would have come up with the same narrative, but perhaps I had the same feeling as you did. When people impose different narratives upon your work, do you find yourself wanting to leave even more ambiguity? Or will something miss your intention and end up in an even more interesting place?

I don’t really try with my titles. One has to try a little bit hard, because words don't come easy. Sometimes they do, and some of my best titles just pop into my head like a melody. If I don't have an easy-to-find, poetic title I quickly go to descriptive, neutral wording. If everything has the same level of poetic interaction, it would probably be pretty terrible. You don't want to be on broadcast all the time.

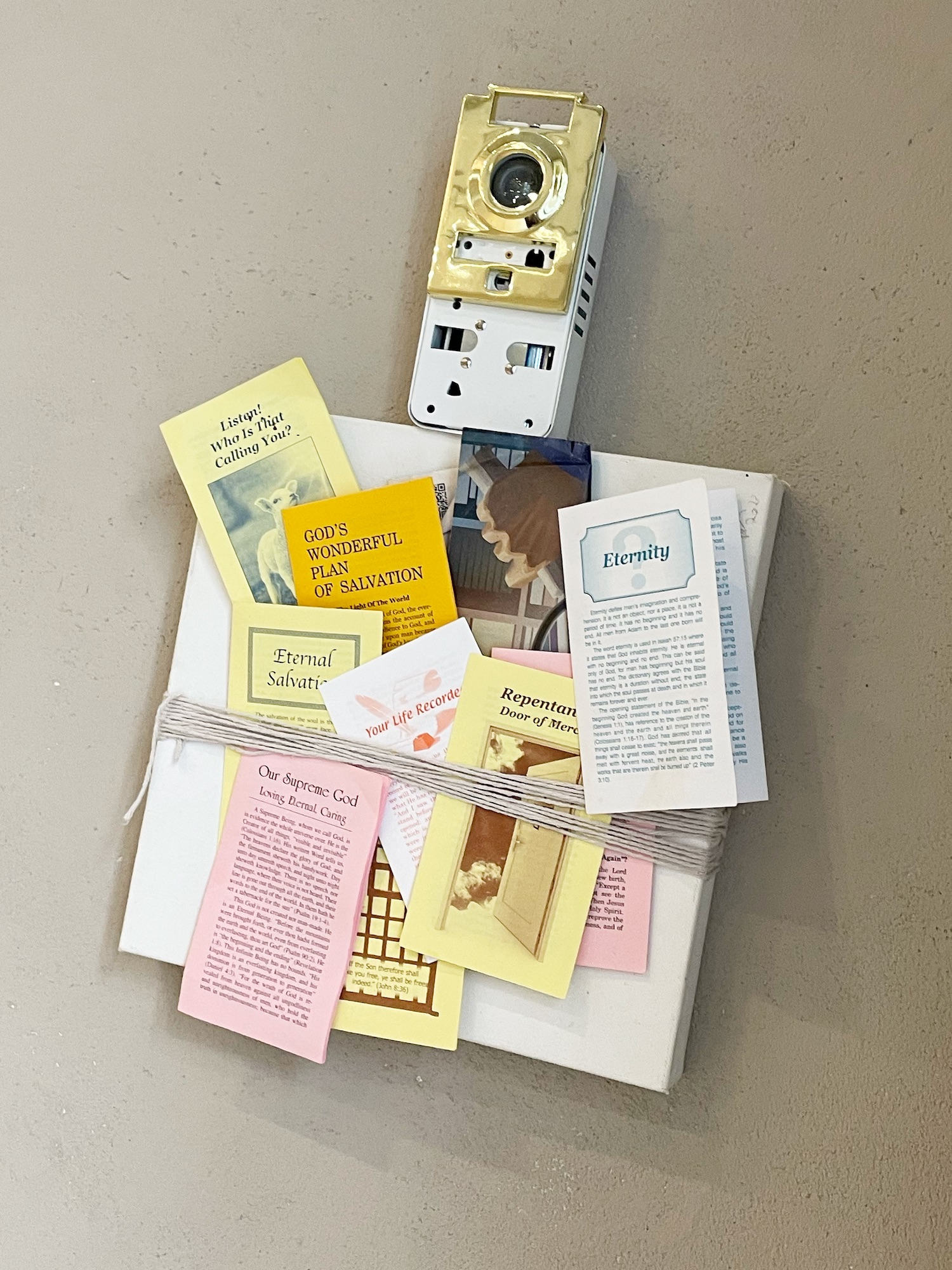

It is interesting that you mentioned placing titles next to the pictures, which is something I considered this time around. One thing that went a bit wrong for the MoMA show was our elaborately produced brochure. The brochure for the exhibition was placed in a dispenser as far away from the entrance of the exhibition as possible. People entered the show without a guide and walked through 18,000 square feet of exhibition space without a single label. I like many aspects of that experience, but I also thought it might be nice if people could have seen the titles.

Commercial galleries don't typically have labels, so for this exhibition, I thought about putting labels here. But even though it is quite a sparse installation, it would be impossible to insert a label. So instead, for this installation, I insisted on a physical work guide to be included at the front of the gallery. I have seen many more people walking and looking at the titles as a result.

You pay such attention to these small decisions because the sparseness means each element must stand alone. So, each individual thing becomes more important.

Exactly, and I love that you pick up on that. You cannot pretend that it is nothing! I mean, you cannot open up a huge white space in Manhattan and place meticulously presented objects in it, and decide to not care about your decisions. Everything has to be thought of. I think I have a natural tendency to see things from different angles at the same time. For example, I placed small lights in my video installation because I didn’t want people to feel lost in such an abruptly dark space.

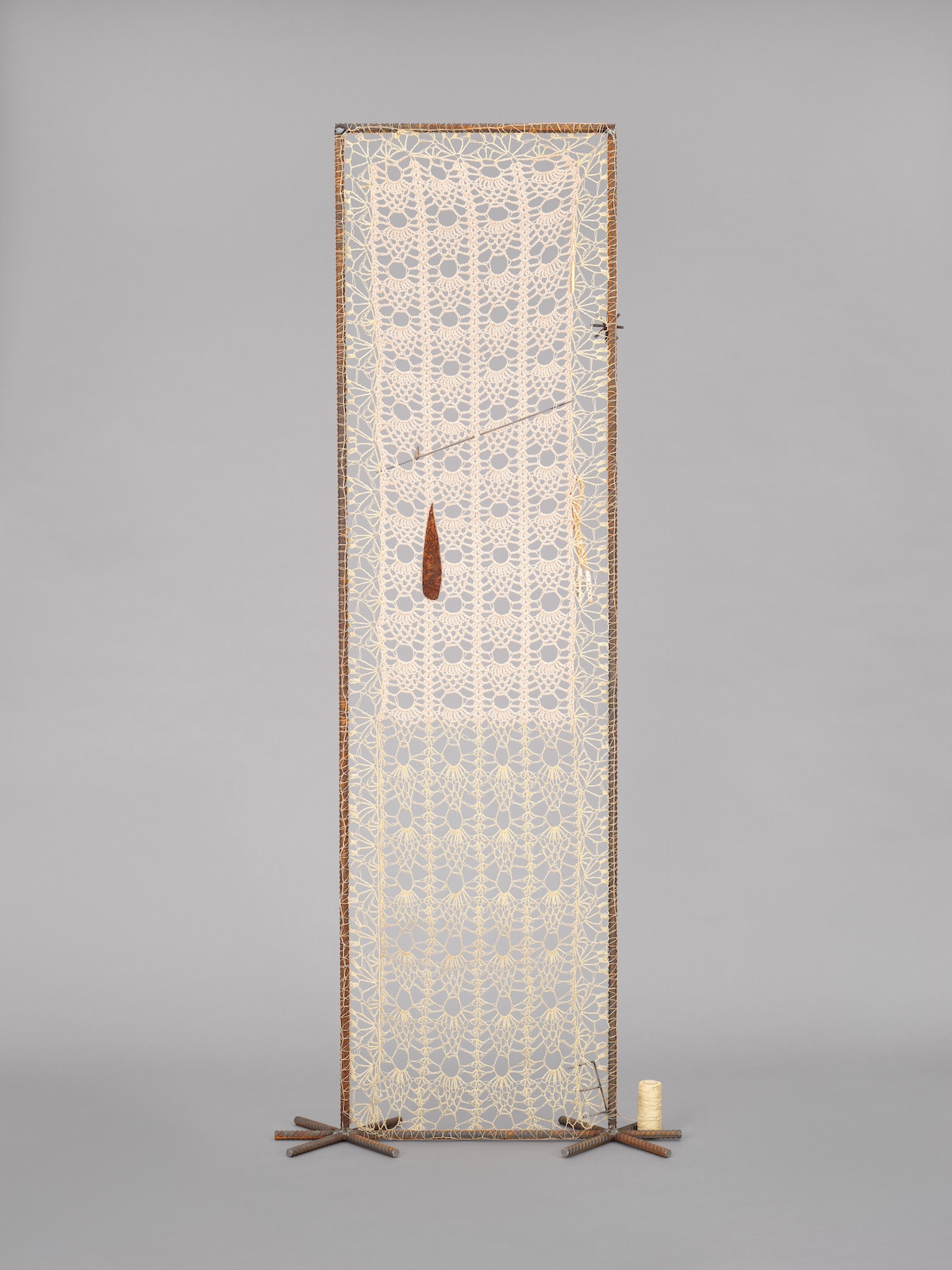

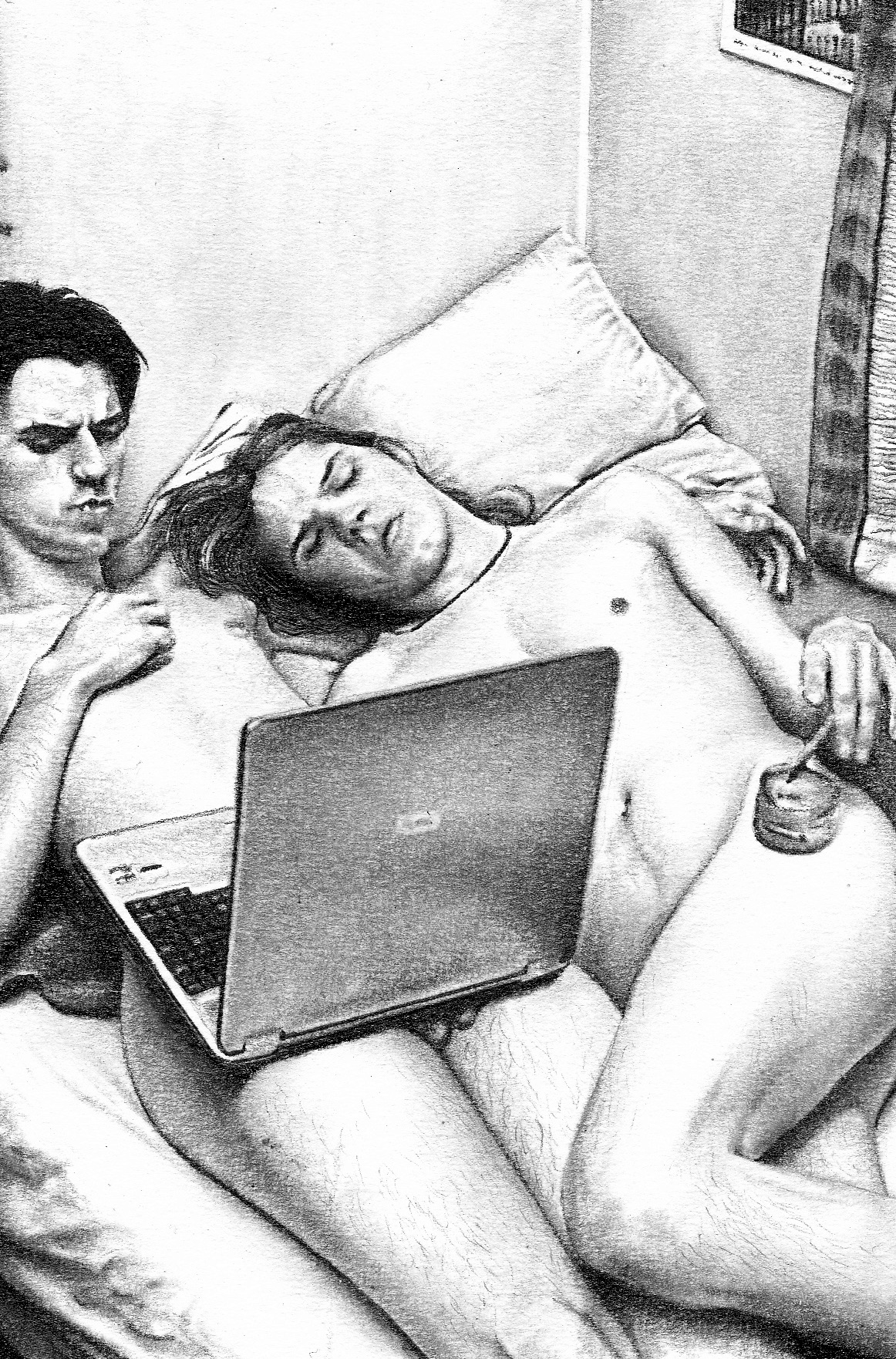

Wolfgang Tillmans, Watering, a, 2022 Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong;

Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

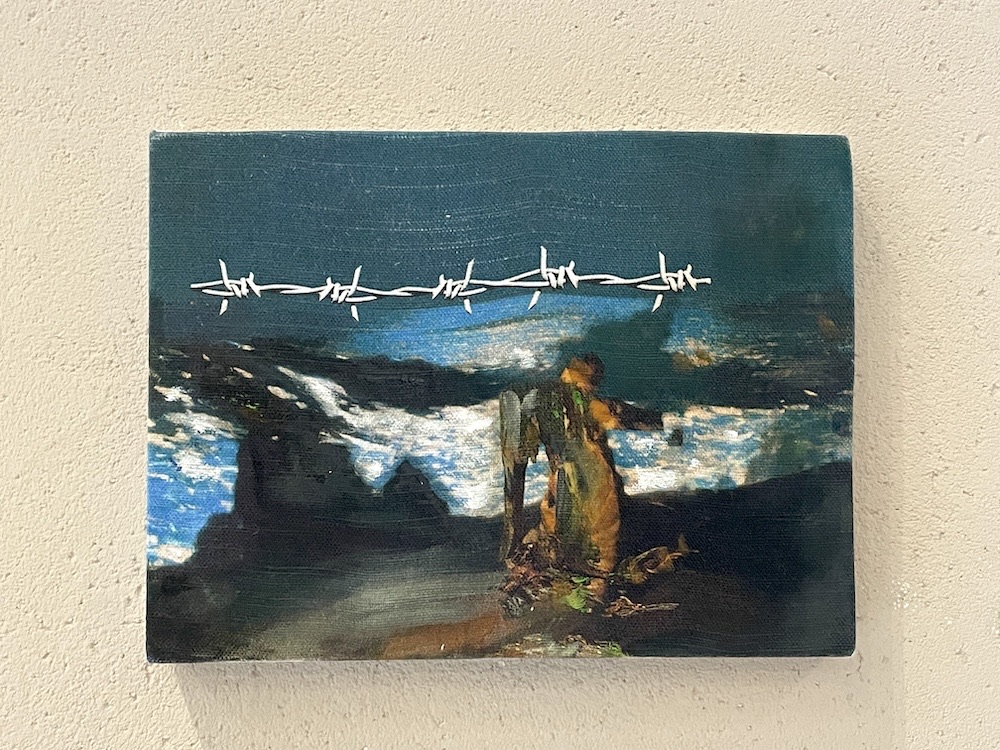

Wolfgang Tillmans, Rain Splashed Painted Life, 2022. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong;

Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

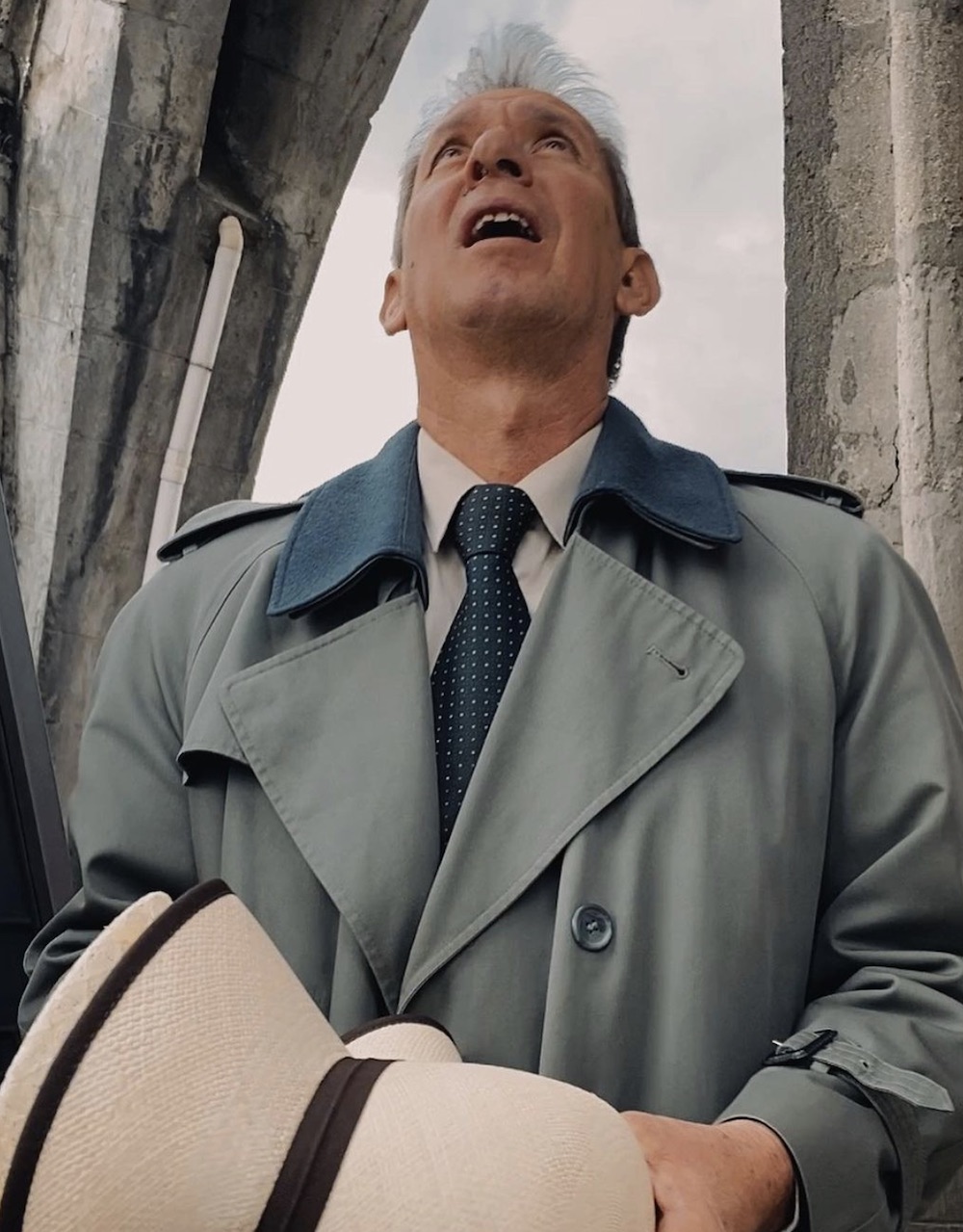

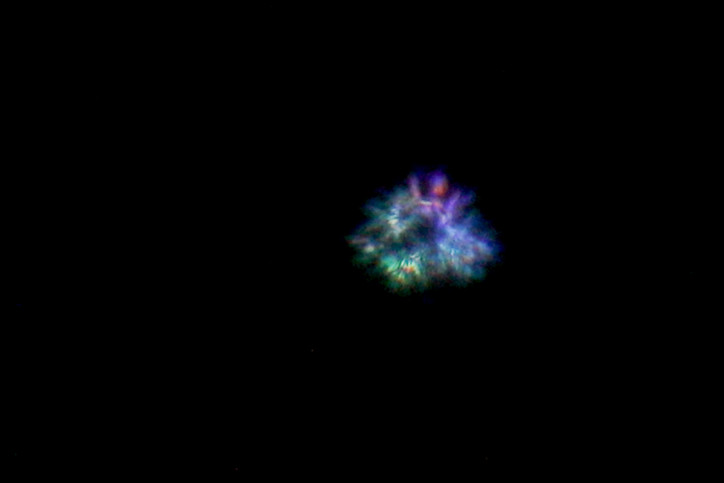

Wolfgang Tillmans, Seeing the Scintillation of Sirius Through a Defocused Telescope, 2023 (still) Courtesy David Zwirner,

New York/Hong Kong; Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne; and Maureen Paley, London

You have spoken about appending expectations with an unexpected decision. Are these surprises, curveballs perhaps, still important to you? Or has sincerity become the driving force of your decisions?

I think that to be genuinely interested in a different perspective is sincere. Throwing a curveball is too strategic because you are really trying to jolt the other. The main consideration would be achieving an effect in the other. When I notice that, I hold back. That cannot be your motivation. Your motivation has to be your own interest. If your desire is just to surprise, the audience will feel that.

I find that in art making, the intention speaks louder than the action. Real change is difficult, and one can also be lazy. There is so much change in the world, and the questions we face are enormous. I have to constantly evaluate the meaning of my work in 2023. We are in a big air-conditioned space with electric lights on all day and got an air cargo shipment to bring all this over. What does all this cultural activity mean within the setting of 2023?

I was also thinking about it in 1996, when I carried three large photographs in a small poster tube––which I had brought as my hand luggage while traveling––with me to MoMA. We glued them together in the atrium. At the time, I was thinking about it as CO2 footprint minimization

Earlier in our conversation, when I took a photo of you, you permitted me to keep something for my private records that you wouldn't want existing publicly. Your work exists ubiquitously online, so I'm curious to hear about your private relationship with the medium. When is an image for you and for no one else? When does something need to enter the public sphere?

There are all sorts of pictures I choose not to show publicly, but often because they are not that good or interesting. Or because something similar already exists. But where your question has potency is about privacy.

I'm thinking about a writer who produces autobiographical work but also keeps a diary for themselves. Do you have the equivalent of a photographic diary?

Yes, I mean there are notes and there are photographs taken already knowing that they are not to be published. For example, a food picture so I can remember a recipe. My still life images have never been about my food. They've always been semi-staged, semi-absurd scenarios that are personal, because they have to be personal for me to be that engaged in them. But they are not there to say, “look at my food, look at my clothes”. When I take an image of a nice plate at a restaurant––which many people have the impulse to post––I keep it as a memory, just for myself.

It's interesting because there isn't this distinction between high and low in your work in terms of the technology or staging. I imagine that the same devices could produce both those private and public images: the memory and the art.

There is one mobile phone photograph in the exhibition, one out of 77. But this notetaking with a phone has become so much a part of my daily routine. I realized this during my recent editing marathon. It takes three seconds to look at and understand each photograph; there is a huge amount of information to digest over the course of 10,000 iPhone notes.

I love that this exhibition is so purely photographic. It doesn't have anything to do with AI, Photoshop or abstraction. Having distilled these 77 works, I am asking the question of the worthwhileness of doing it again. I certainly will not stop photographing, but one has to ask what it means to make more?

I have come back to the chorus of your recent song, “I am insanely alive”. I see this life-affirming quality in your work from the beginning. What is life-affirming for you when these questions arise concerning the direness of an image culture, ecological crises and social crises…

…And the rise of facism all over the world. In a nutshell, if you look overall at the past several hundred years, we are in quite a good place for human rights and a whole number of indices. I believe in the potential of humans to change and adapt, and somehow for good to prevail. Somebody living in Congo probably does not feel that good prevails: for centuries, the land has been ravaged and plundered.

The Ukrainian war, the Russian attack on Ukraine, has probably darkened my outlook more than anything since the AIDS crisis, which was a very existential fear. I find it so perverse that people can sit on the fence for an issue like this. That makes me quite despairing. My positive outlook on life has been put to a bigger test in recent years. I am more critical about how I am spending my energy. Because this is so major, what's happening on these different fronts from climate to American democracy. Suddenly, in Germany, which seemed fairly immune to major far-right political gains, now seems less assured.

But the positive outlook still remains.