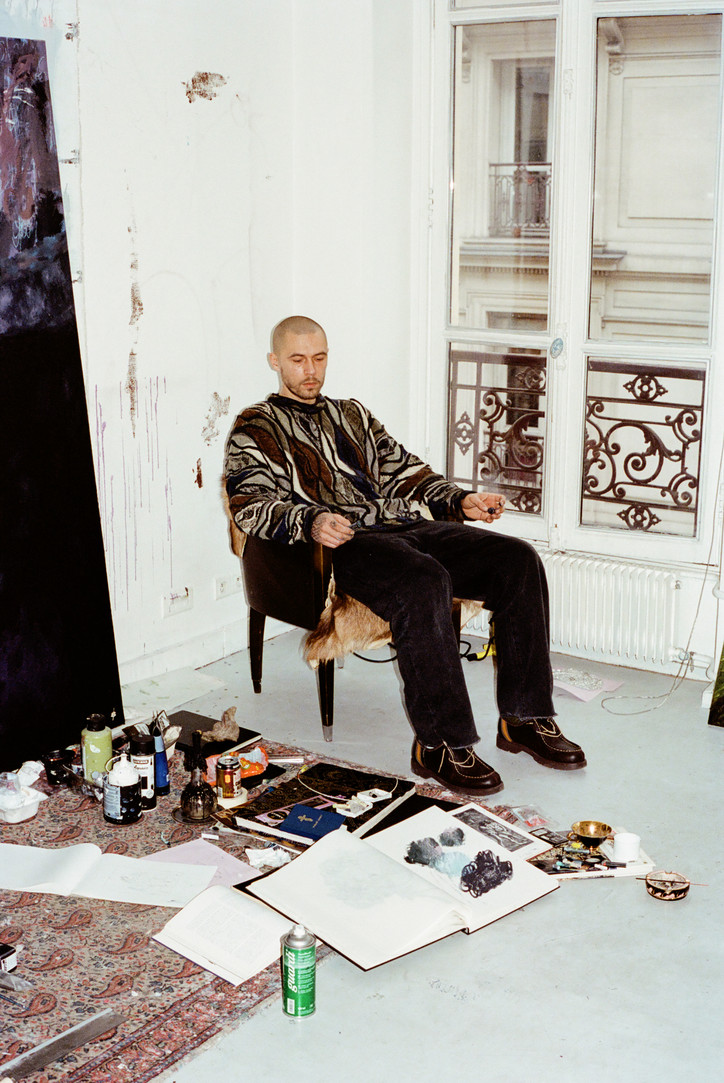

Asymmetrical Symmetry

office will meet you there: below is the scoop on his new show at Sean Kelly.

Tell me about your work at the gallery.

The show is kind of a continuation of a conversation that’s been happening for the past few years in my work. There’s a core of my practice that’s been based around this idea of dealing with authorship, and the role of a singular author versus these external constituents. I think a lot of the way that that becomes manifested in the work is through these acts of receiving or looking at the exhibition with an open and nuanced mentality. Physically, that takes hold in the work and creation through the materials. I use dye which sort of physically merges with the object. And the way those two mediums work together is they create their own vernacular.

So, then there’s this relationship between the image and the object, where the image is quite literally dictated through the object, and that relationship is reinforced again through the breaking of the image through the panels. That relationship of image and object bleeds through into another sort of important narrative, which is the role of the viewer in the work. So, the image is never entirely created on my part—there’s always this sort of gap left between the panels, where there’s this automate, phenomenological process in the mind of the viewer, much like how film works through a series of still images.

In both of those cases, there’s a sense of relinquishing control and authorship to the materials, and the way they function on their own terms, and the way the image and the object relate to one another, and the way the viewer has this sort of automated role, which comes a lot from Duchamp—the readymades as a creative act that doesn’t belong to the person who made it, but to the culture and the society that decide to perpetuate it. And then further, which directly relates to the show, is through seriality and repeated motifs across multiple panels, the work will articulate an environment. So, they often times are drawing attention to some sort of idiosyncrasy of a particular place or space, whether that be an expectation around the cultural condition of that environment, or even in this case, where quite literally some aspect of the gallery will become a unit of measure that dictates how the work unfurls throughout the exhibition space.

I just watched this documentary about Sol LeWitt. Are you familiar with him? Apparently, he would create lines that were dictated by the angle of the door, then write out an equation and send it to the curator. Your work reminds me of him.

I actually have one of those wall drawings at my desk in my apartment. He’s a very important artist for me. I don’t know if you ever read Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation, but it’s essentially a case for seduction in art—a case against the notion of strictly conceptual, subversive work, which was very prominent in the '50s and '60s when she was really active. But with Sol’s work, what I find is, there’s an extension of a relationship between the heart and the mind—there's this rigid intellect that drives it, but also there’s something very poetic and intuitive. The logic breaks down pretty quickly, and it’s allowed to break down—it straddles the line between the more intuitive, poetic, visual—or let’s say retinal—work, in the language of Duchamp, but also has a really strong conceptual backbone which guides it. That's a current that’s very important to me, and hopefully will flow through my work, as well.

I always like artwork where I feel like I’m being made into a pawn as a viewer—like the viewer is all of a sudden a part of the artwork. Is that what you're doing?

Absolutely. I often talk a lot about dance and choreography in relation to installations, because like I said before, when you go to a museum, or a gallery, or an exhibition space, there’s a lot of cultural preconceived expectation as to how one’s body is meant to engage with that environment—how you should behave in that environment—and I think those expectations really change the way people move through a space. A lot of times, that can feel alienating to a person—almost as if they’re imposing on this mutual environment. I think formerly, the viewer was often ostracized from the experience of art, and I think this is really important: my work isn’t about looking at a single painting. All of the attention, it overflows off of the object into the experience, and the experience is not just contained within the walls of the exhibition—it extends to the viewer and how they feel in the space and their sense of body awareness, of how they physically relate to the work, the sense of rhythm and pacing. So, the viewer is a really important constituent in my practice.

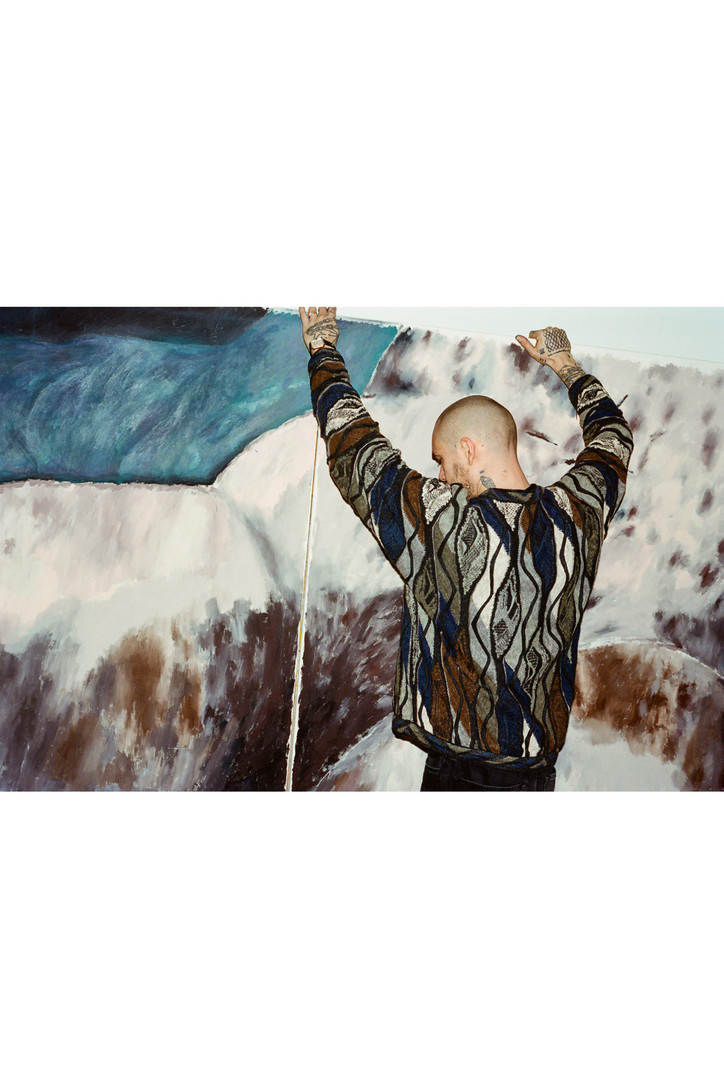

I tend to use this metaphor a lot when I think about art, and especially with yours because your pieces are so large, they’re almost like portals—like you’re being drawn into another world. Do you feel like your work does that?

I think all paintings have this window effect where it's almost like watching a film, or looking through a window into a weird place—it gives you the opportunity to leave the immediate experience and go someplace else. I would actually say that my works are kind of intended to do the opposite, actually.

The opposite? Why?

Yeah, in a way. Instead of being so self-reflective, I think there’s this tendency to look at the external world around the works rather than into themselves—they’re very peripheral, if that makes sense. The practice as a whole is like this little bird in your hand—you can’t fully grasp it, and if you try to squeeze it, it’ll fly away. Every little element in my practice bleeds into something other than itself. The material bleeds into the object, the object bleeds into the space and all these preconceived conditions—it’s really slippery in that sense. So, in a way, yeah, I know what your saying—there is this sort of depth to the way the dye dries on the canvas, and because of that you get the sense of another space. But my hope is actually to reinforce the space that it’s in.

So, instead of being a portal into another world, it's a door int this one—it highlights the physical space around it.

If it's a portal, I hope it’s one that allows the viewer to look deeper into themselves. It's an opportunity to have a mindful experience and acknowledge parts of your environment that maybe you were overlooking, and instead of going around reality, it goes through reality into something hopefully deeper than before engaging with the exhibition. But I wouldn’t say it’s a portal to an imaginary place—I would say it’s a portal into something you forgot existed, or maybe you were too busy, or too preoccupied, to remember. I want it to feel like a memory for someone—like there’s something very comfortable, and comforting, and familiar—almost as if there’s a mirror into something within.

Let's talk about your use of repetition. I’m in an MFA Program and we’re currently reading these ancient texts, like Gilgamesh, and the professor pointed out all of the repetition. Can you comment on your use of it in your work? It seems really important.

For starters, there's this relationship to the natural world that we learn, sort of like a universal code for beauty—there's something deeply, intrinsically satisfying about seeing the same thing happen over and over again. But that’s on a more superficial or aesthetic level. Conceptually, it’s driven by the fact that my practice is situated around this idea of acknowledging a situation, or a thing, or an ecosystem as it is. Let’s say we’re talking about art, and ecosystems of art, and how all these external constituents function—you have the body of work, the viewership, the author or person who made it, the institutions and places that exhibit these things, and all of these little, tiny moving parts add up to something greater than themselves. So, I think there’s this philosophical non-binary implication that drives my whole practice which is, I don’t want any of these single reeds to be enough—I hope to devalue any single one of these forms as carrying a full, formal weight.

During Modernism there’s this reverence of the author, and then in Post-Modernism, they’re trying to counteract that and say, 'No, the author doesn’t have this much importance, the viewership needs to play this very significant role.' I think there was a lot of degradation to the author during Post-Modernism, and I think another form of the relationship to that, which is the space I hope to occupy, is instead of revering the author or degrading the author, there’s a third important viewpoint: acknowledging that the person is present and necessary to create the container. So, I want my aesthetic vernacular—the forms, and colors, and scale—those are acknowledgments, or gestures, of my presence as not just an author, but as a human.

So, under this third notion of authorship, which is sort of acknowledging it without putting it up or down, or accepting that they’re there and they have to be, it should serve a purpose beyond just itself. That’s the reality that comes into play for me. Like, I’ve made these formal decisions in that I've made a painting, it’s a color and it does everything a painting has to do. But then it becomes serialized, so it’s no longer about revering or admiring a single work, but more about how that object can bleed beyond itself to acknowledge an entire environment—to show that I’m present but not give the full weight of authorship to me. It’s extended beyond my hand, to all these other things.

'Asymmetrical Symmetry' will be on view at Sean Kelly Gallery through October 20th.

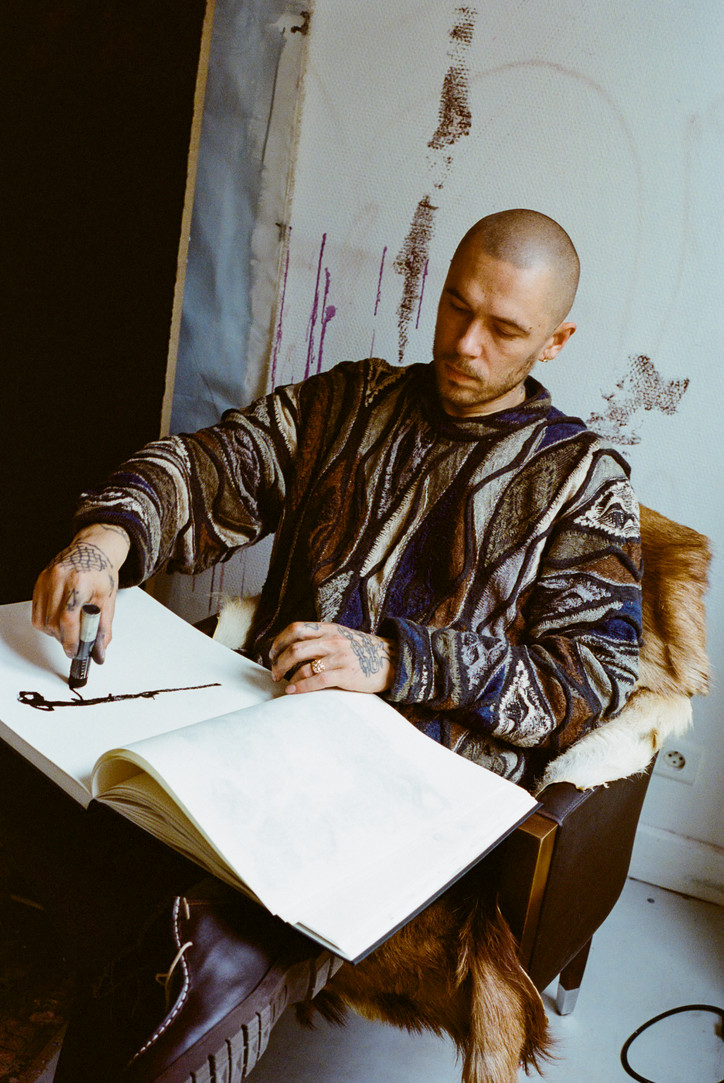

Photos by Jason Wyche; courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.