In Creation There's Destruction

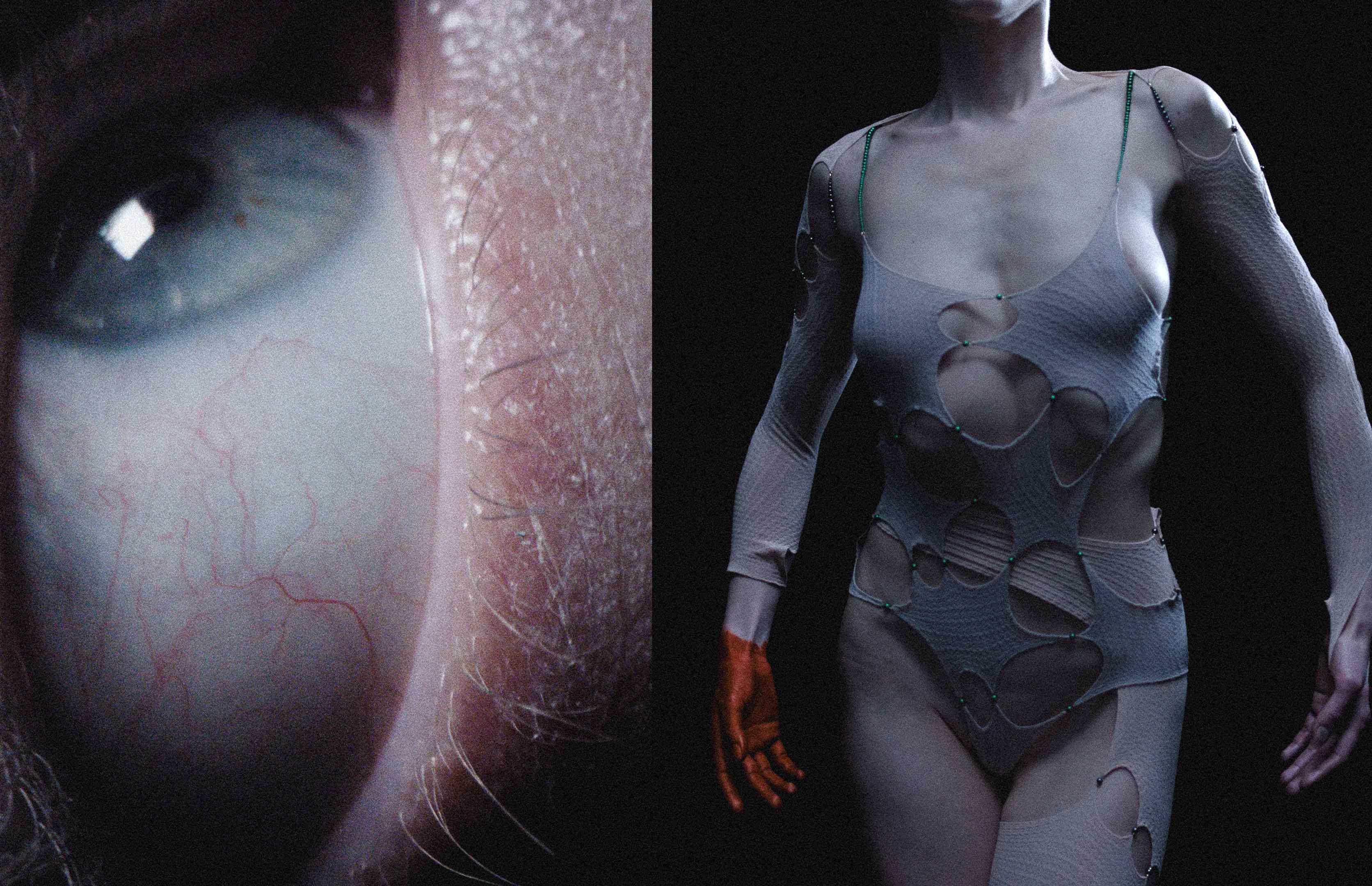

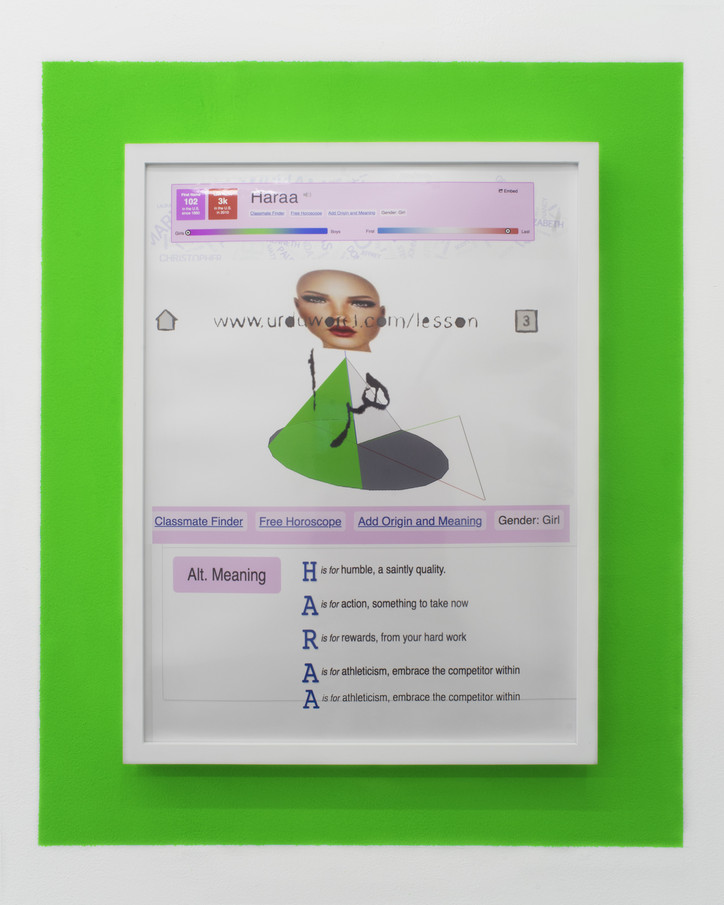

Her aesthetic is drastic simplicity crossed with florid intellectual eloquence: internet Clipart and a robotic digital audio voice clash, mesh and blossom through concepts of God and country, nuclear power and nature, family ties and, of course, the digital interface that has become the go-to medium through which we navigate it all.

After a walk through Rubber Factory, office spoke with Majeed about Islamic kitcsh and theoretical physics.

Tell me about the show.

So, the show is called In the Name of the Hypersurface of the Present. It’s based on two years of research I did around the nuclear history of Pakistan. The investigation started with looking at a monument that commemorated the nuclear armament that happened in the 1990s, and the monument doesn’t exist anymore, so in a way, the research and the work retrace this recent past. I use both material I got from Facebook, nationalist groups around Pakistani military, and also I looked at my grandfather’s photographic archives—he was an analog photographer, and he had nationalist leanings, so his political stance was very pro-Pakistan. Then, I also looked at Urdu literature around science and poetry—Urdu is the language of Pakistan.

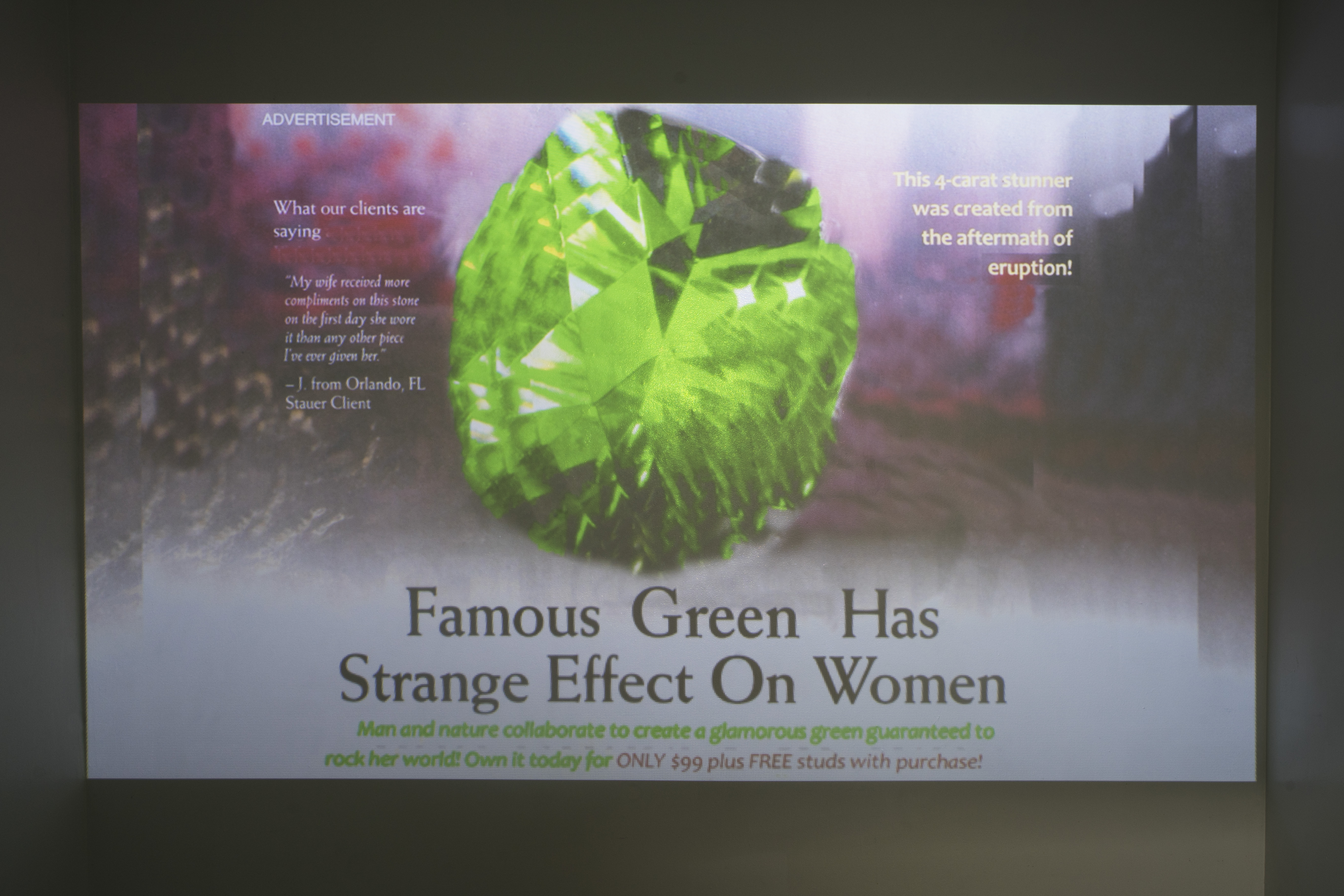

So, it’s an amalgamation of all these things, but when you go to the show, it’s based around this idea of green, and the green kind of represents an intersection of Pakistani nationalism. But it’s also the color of Islam, which it’s known as. Saudi Arabia uses green as a color, and Malaysia—multiple countries look at the color green as the color of Islam, so it gets used in a lot of Islamic kitsch. I also refer to green as the digital interface, this idea of green-screening, a space for projection. Green is also representative of the military, and I'm looking at the nuclear history, the military history. Using the color green also refers to landscape, homeland, so in a way, when you enter the show, it’s an unfolding of that—where green refers to landscape and body, and this intersection of poetics of love for homeland, as well as science and state propaganda that’s used to uphold nationalist love. So, it’s a mix of all these things.

Do you know what happened to the monument you were referring to?

I’m actually working on putting together a lecture performance where I chronicle the history of the monument, looking at the rumors. Because the state monument is this really ugly fiberglass reproduction of a mountain, it basically is not taken seriously by architects, academics. So, the the motif of the mountain itself becomes like looking through the perspective of a monument, a kind of alternate history. That’s how I was trying to look at it—through this monument. One part of the lecture performance is basically gathering all the pieces of information that have been put out there by the state. So, for example, the monument was built in the 1990s and it was built to commemorate a holiday that translates to ‘The Day of God’s Greatness,’ and it happens every year, and the monument was built to bring the public—meaning men, who occupy public space—to come to the monument to celebrate.

So, it was built in different metropolitan cities—in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. In Karachi, it was destroyed in the early 2000s because the father of the atomic bomb in Pakistan—the guy who headed the nuclear project—he got arrested by the state because there were rumors that he leaked nuclear scientific knowledge to other countries. So, he was under house arrest for ten years. During that time, because of the weight of nuclear history and religiosity is so intertwined, they look at this person kind of as a figure to represent their religion and nationalism all in one. So, when he was arrested, the public—and by ‘the public’ I mean very specific male patriarchal, the dominant class—they ended up burning the monument. In Lahore, the monument was built near a railway station and it was taken down by the state because there were rumors that the station was invaded by terrorists and they used the monument as a shield and attacked people in the railway station. Then in Islamabad, the capital, in 2016, the monument resided in this roundabout, and due to the current urbanization policies of the recently deposed prime minister, they were expanding roads throughout the country, and the monument was supposed to be relocated. It was removed and destroyed so they could expand the roads, and it was supposed to be relocated in a major park in another part of Islamabad.

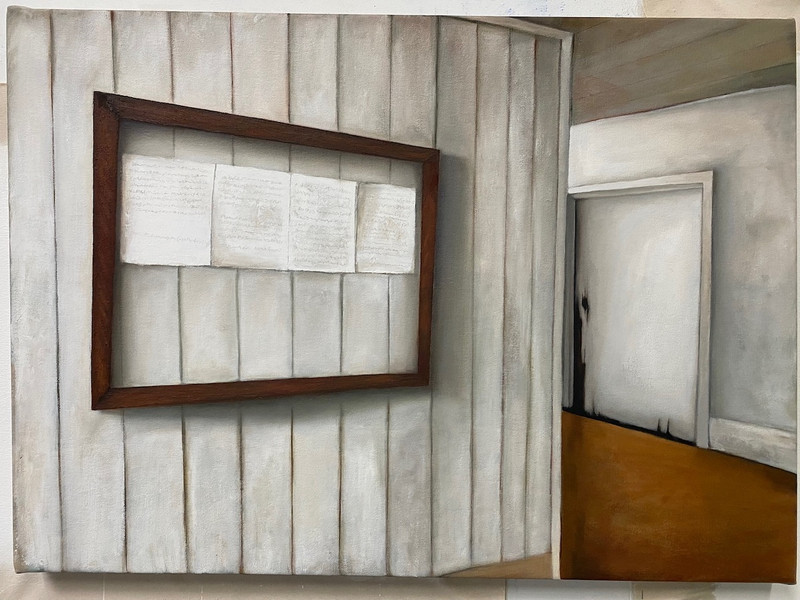

One of the main videos I made for the show starts with the relocation of this monument. It’s thinking through this monument that is returning to a kind of pure, natural—even though a park is not necessarily a pure landscape—but in a way, it’s a return to origins, a return to nature. So, that’s where the entire show is encapsulated—these references to flora and fauna and landscape and the garden and the way of the garden.

There’s a kind of female re-imagining of history happening as well, correct?

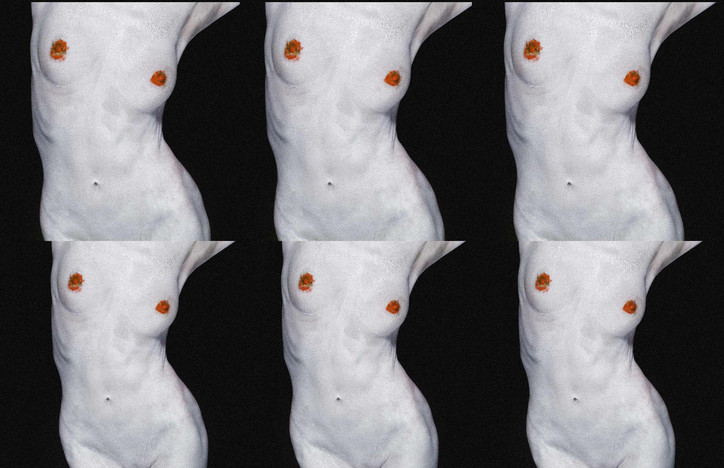

In the first two videos in the first two rooms, is my voiceover, but my voiceover is through a fictional poet. So, there’s a querying of this poet, who represents the state. It’s a feminist re-articulation, but also making visible how women are used as containers for state propaganda. The atomic bomb or landscape can also be intertwined with the idea of the woman, the rebirth of the nation—so, in a way, making that visible is a part of the project. The female form is visible even in the reference of the flower—in both of the videos in the front, there’s a constant reference to flora, and that is a direct reference to the woman. In the back room, in the projection piece, there is the visibility of the female as a kind of sampler of the way in which you can gain the purest national love, the performativity of pulling the ear, and allowing the green light to enter certain parts of your body. I actually published a spec fiction piece about green light entering the body igniting the motif of the cone. This overall large, two-year project is continuously expanding, so what I’m showing at the gallery is like an excerpt to test your taste about all these ideas.

It almost reminds me of a video game—it feels like there’s a plot.

One of the narrative tools is looking through the interface. I used certain imagery, certain memes, and collaged them and played with them to see that there’s a kind of violence within this imagery that is disseminated and passed down.

I just read this article about how the internet and social media’s original goal was to make a more open society, but actually it’s helping autocratic urges more than it is helping people to be more open and democratic. Do you feel like this connects to your show?

Definitely. There’s a connection to these nationalist uprisings and conservatism—these uprisings that have been happening for the last few years—and it’s looking at ways in which the digital interface is subsumed by those nationalist movements—it becomes a tool used as an extension of state propaganda. You can look at the ways, beyond the context of Pakistan or any specific state, that these patterns form. Post-Arab Spring in Egypt, for example—the state has so much control over censorship, over the internet, and that was the very tool to bring people together and mobilize people to protest, but then that very tool has become detrimental to the very people that mobilized in the first place. It’s very easy for the state to target these individuals.

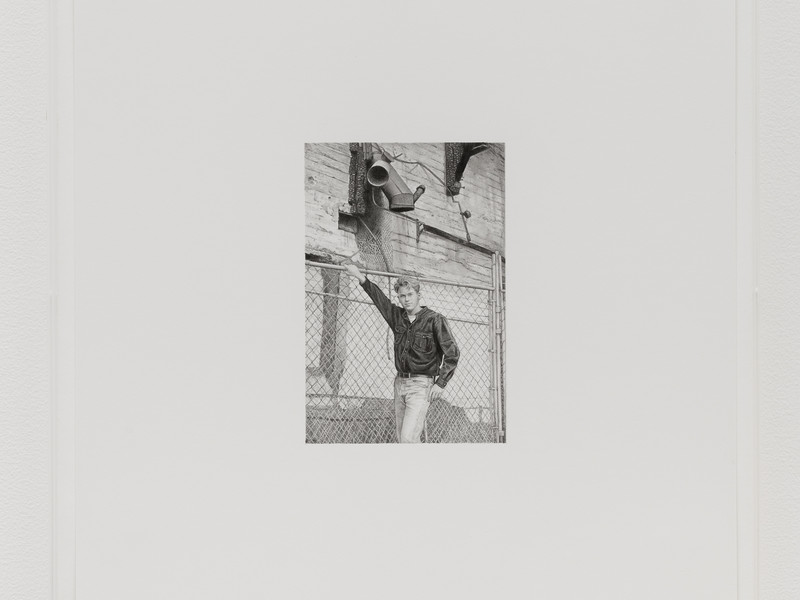

What’s interesting to me in regards to the digital interface are the subtleties. My interpretation when looking at the nuclear history wasn’t this kind of spectacular dominant narrative, but looking at the smaller, the micro-lens—looking through these memes that are disseminated that are kind of subversive techniques of state propaganda. I’m also looking at say, my grandfather’s photography, that is quite beautiful, but the fact that he showed at a government institute in the '90s in Pakistan reflects his politics at a certain time as someone who’s an artist. So, in a way, it’s a very difficult line to draw between the military, art infrastructure—it’s all subsumed. That’s how the nuclear project came about: in the name of God. So, in the name of God, the nation of Pakistan had to protect itself because of larger threats. So, there was a lot of material through media that was disseminated about becoming a nuclear power, and at the start of it, the rhetoric around it was ‘This is the only way,’ which is how state propaganda works. It was embedded in love, and beauty, and in the name of Pakistan, so therefore it’s a very thin line to distinguish what's real and what isn’t. And we can see the implications of that in other nations today. So, I use Pakistan as a site, but I’m also thinking about larger, global ideas, of how the state functions and how the interface is used. I’m also interested in how the body, as a citizen, reacts to that, and how it’s used in that whole process, even through the digital interface.

I’m interested in this idea of Islamic kitsch you mentioned earlier. I love the idea of kitsch—what do you define it as?

Right. I was talking about the color green and how it’s used in a lot of religious iconography as a symbol of Islam. Throughout the show, there’s a juxtaposition of internet art—I wouldn’t necessarily want to label it as kitsch—but there’s a lot of collage. There’s a lot of material from books—for example, the Urdu books I refer to all have appropriated imagery from let’s say Google, pixelated imagery. The colors, the luminosity, they’re actually from the materials I gathered myself. So, it’s not necessarily labeled as Islamic kitsch, but it’s a form of publication that is used in Pakistan, and the internet—I appropriated from that.

The title of the show is really bizarre and fun. Where did it come from?

It actually refers to ‘In the Name of God’ rhetoric. ‘Hypersurface of the Present’ refers to theoretical physics, it’s an actual theory—it’s a measurement of space and time. There’s an actual formula. I, basically, in the digital publication I’d mentioned, take diagrams and references of the cone, and write this fiction around it. So, the show is a combination of these poetics—of science and how the state represents science, and this state religiosity.

I’m still stuck on this monument you were talking about.

It was the start of the whole project, actually. I can see why—it’s a replication of nature, tied to a religious holiday and commemorating nuclear arms, and it no longer exists. There’s a lot attached to it. In the lecture performance, I use this fictional poet to speak about the poetics of that—when is the moment that this monument exist? Is it the moment that it’s destroyed? Similar to the atomic blast—the atomic blast, or nuclear power, is only visible in this kind of destruction. The fact that none of these monuments no longer exist—is that a reproduction of that power? One of the lines in the videos is, ‘In this creation there is destruction, in this destruction, it can be created.’ There’s this fine line—which is what nuclear power is—there’s this suspension and anticipation. That’s the narrative around nuclear power.

I’m actually going back to Pakistan in December for another project. I’m interested in expanding another chapter of this project in relation to a specific poem that my grandfather used. So, the reason why I introduced my grandfather’s archival material was that I found out that my grandfather gave one of his photographs to the father of the nuclear project. There’s a photograph of my grandfather giving his photograph to that guy, and there’s a poem that’s written on the bottom of the photograph, and it’s a reference to Abraham when Abraham was thrown into the fire and flowers bloomed, and that’s one of the verses I used in the collages. It refers to a nationalist poet, Allama Iqbal. So, I’m interested in writing another chapter talking about the photograph itself, and the relation of that quote referring to Abrahamic fire, and this nationalist poet who was censored with this poem, but it is still, somehow, a part of the nationalist imagination.

'In the Name of the Hypersurface of the Present' will be on view at Rubber Factory through November 11. Visit the online gallery here.

All images courtesy of the gallery.