Dystopian Glamour

Tell me about your work.

Steve: Dorota and I met in Kaui in 2004 when I was going to grad school out there. We started collaborating on all these art projects and decided Hawaii wasn’t going to give us the platform or backdrop for the type of work that we wanted to do. So, we decided we wanted to move to one of the post-industrial cities—Baltimore, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, even Buffalo was on the list—but Detroit was where I grew up. So, in 2007, we got a place that was really cheap—it was $250 a month for this big warehouse space in Eastern Market. We then started a corporation that same year—we legally registered the corporation as a new and original form of art. We wanted to use it as a platform for critiquing corporatism, advertising influence, value and identity, and branding. It’s a conceptual art project and we wanted to create art under this label. We thought it would be funny if the corporation created nothing, had no profit, and created these ‘interventions’ under this name.

Does the corporation still exist?

Steve: Yeah, it’s a legal entity. We aired a TV commercial once. It’s like aesthetic relationalism—you’re sitting there, you’re watching TV, and all of the sudden, we appropriate your TV and you become a part of this performance, a part of this moment. It was funny because we were appropriating these moments that corporations try to use to influence you. We went in and basically—I don’t know how to put it.

You stole time, in a way.

Dorota: Right, we just used the TV as our medium. We were trying to do what corporations do, and how they influence people, and how they push their agenda on people, and we kind of appropriated that space. We used street art to do the same thing.

Steve: We saw it as performative, where you become a part of the moment—and it’s not that much different from our unsuspecting public work where, suddenly, you’re a part of it. The reason we love street art and public art is that moment when you’re walking down the street and you see something you didn’t expect, and it kind of changes your way a little bit. That’s the kind of work we’re really into. Through the corporation we see each project as building upon this narrative—one piece might be about one thing, another piece about something slightly different, but as a whole, they connect through this conceptual narrative that is our brand.

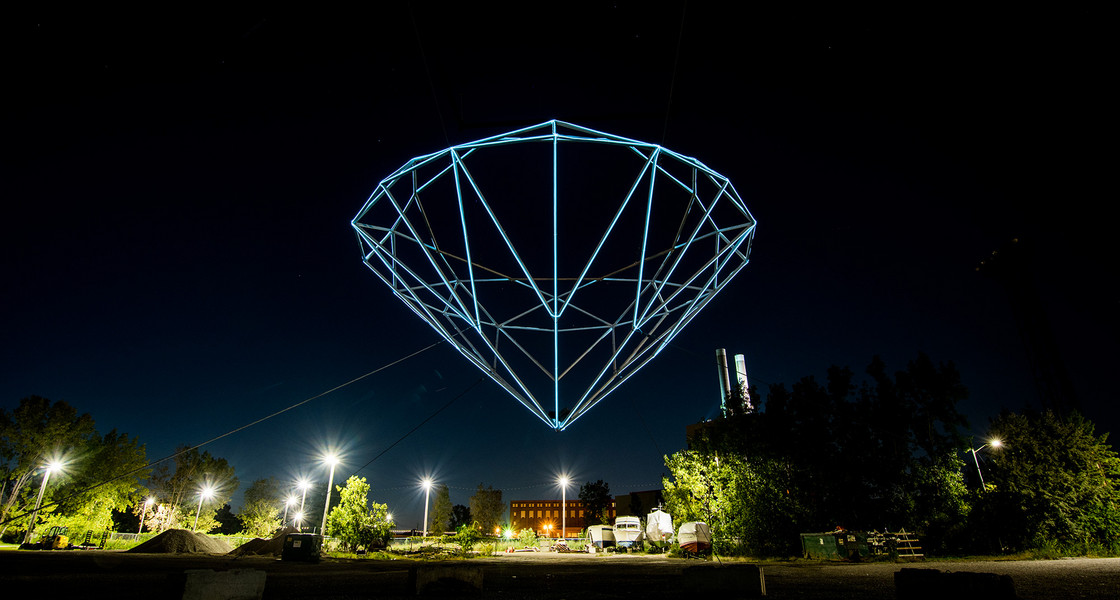

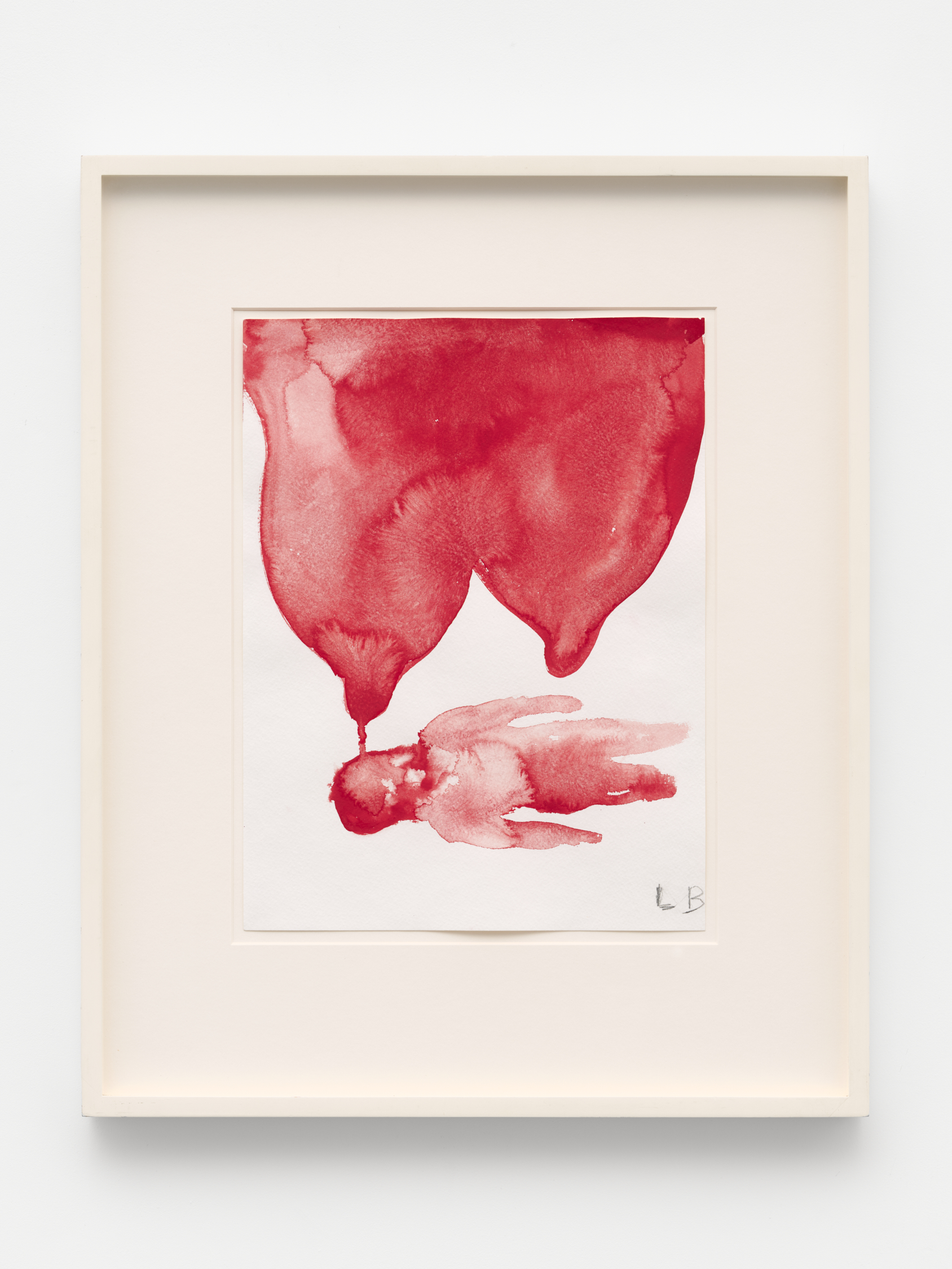

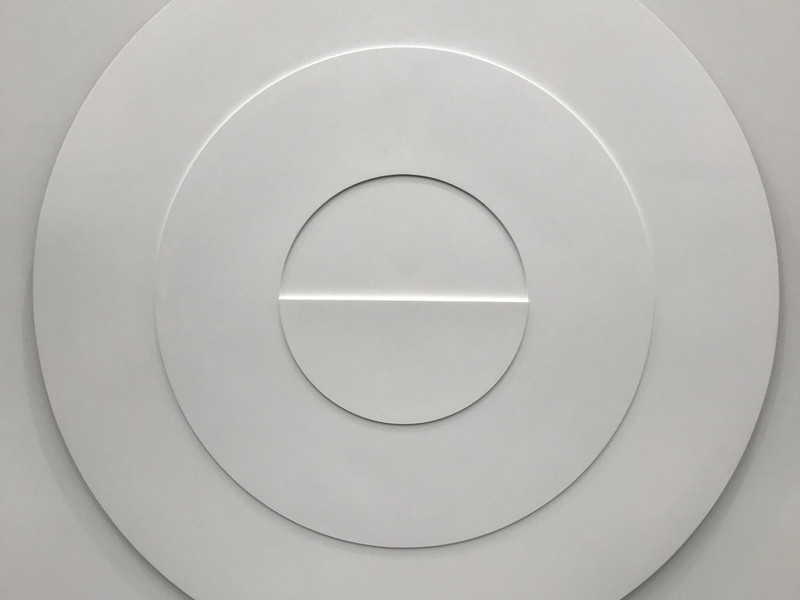

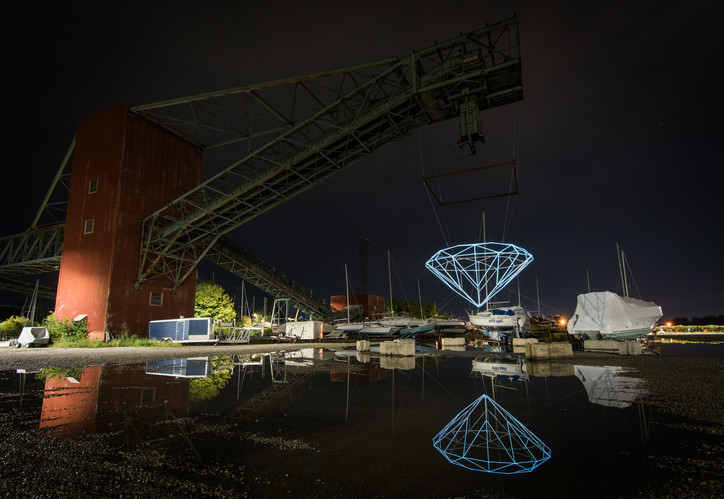

Above: Steve and Dorota Coy at DTE Decommissioned Power Plant and 'Diamond II.'

Do you feel like this project was a departure for you?

Steve: Maybe only in medium—otherwise, not really. It’s still in a post-industrial context, things that have been left behind, forgotten. We did this farm piece in rural Michigan and it was a departure from our traditional context, but the meaning was still there. We like to appropriate all that environment to contextualize our work.

It’s interesting too, to think about a corporation as an entity. I love the idea of a corporation as a person, but it’s not a real person. Do you feel like you play into that?

Steve: We love the anonymity that rides behind that. It’s one of those places where art and law coexist in a weird way, as well as commercialism and branding. You can look it up in the state of Michigan, it’s there legally registered. We have shares allocated for our corporation, we have bylaws written up and articles for the corporation. We’re eventually going to sell shares of this corporation as another public performance art piece.

So is the product the performance itself?

Steve: Exactly. It’s performative. People can own the share of nothing, but the reality is that it starts to play into questions of what value even is. Is there value in these cultural artifacts that we’re creating?

So, it’s kind of like the diamond piece you did for the city, where it seems valuable, but we can’t really take part in it other than looking at it.

Steve: Yeah, we play into those tensions. This piece does that more than anything—riding those lines between really crazy aesthetic beauty, on an art level there’s potential value there, like a cultural value, challenging society, but the diamond as a symbol is exactly what you said: is there any real value or is it perceived value that’s been ingrained into society? Is it merely something people believe is valuable because a corporation told you that because they want to sell it to you?

Especially now that they can make diamonds, so it’s almost like a corporate object in and of itself.

Steve: Yeah and I think it’s naturally embedded into us, too—when you get engaged you get a diamond, right?

Dorota: It’s the idea of corporations using branding to sell more—so we’re using the same kind of ideas.

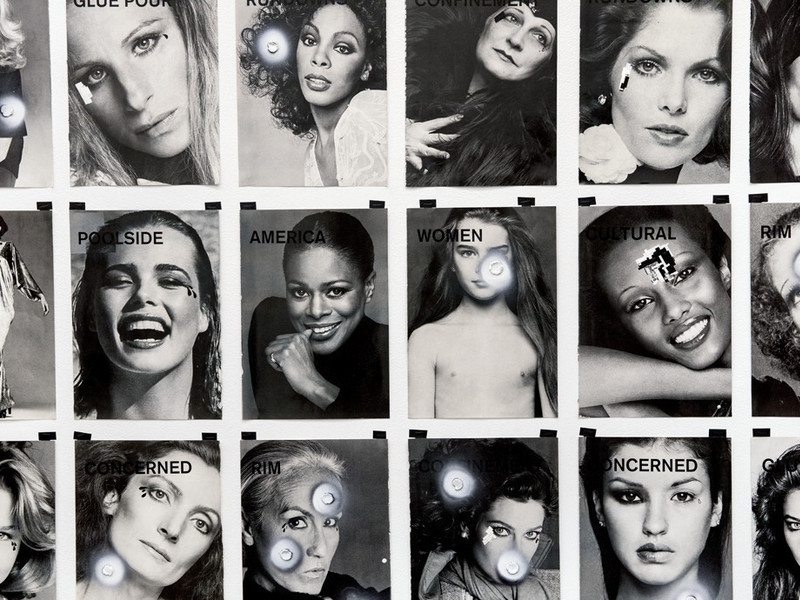

Steve: They’re completely manipulating society. It’s no different than the way magazines might treat the way women are supposed to look.

So, how do you feel like you are manipulating society?

Dorota: I don’t think we’re trying to manipulate society, I think we’re bringing things to attention—that you can look at things differently than what you’ve been told.

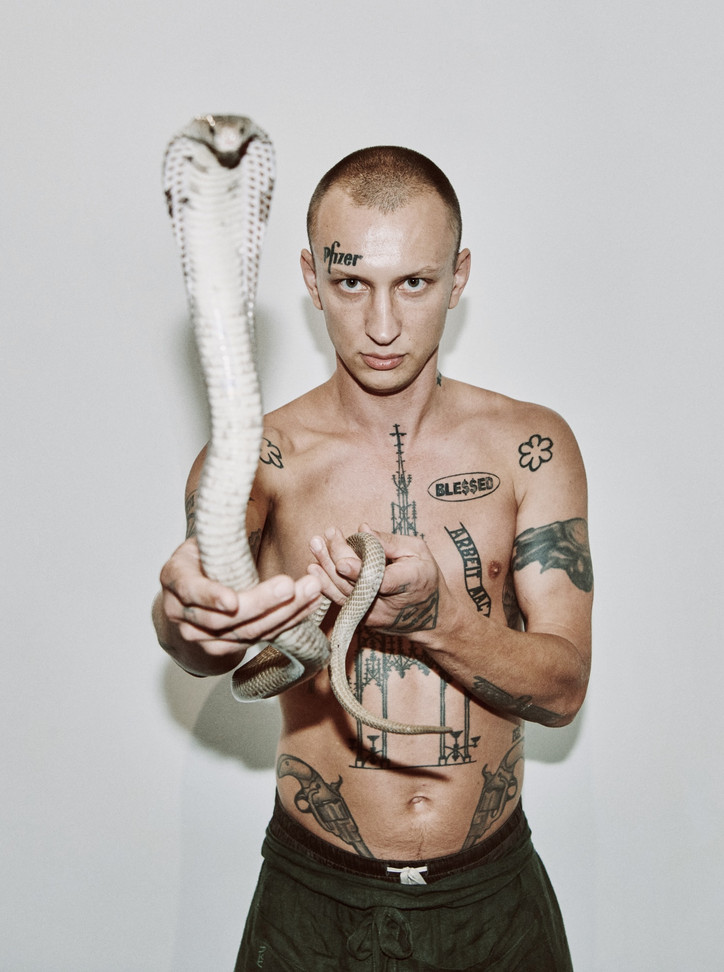

Steve: I think we’re calling out the absurdities. We’re being subversive. We’re being playful—there’s a lot of fun in this. There are these very serious undertones, and we talk about that with the elephant, but there’s also this absurdness and playfulness—like our pigeons. We find them to be these beautiful animals who have adapted to city life, but so many people view them as an ugly, filthy, stupid animal.

It seems like you have a really interesting connection to nature. I looked at your Tumblr, and most of your work uses animals in some way.

Steve: There’s a tension, I think, between profit and sustainability and the planet, and also, I think on a broader note, we’re starting to question what does it mean to be a human, what do we need, what are we doing and why are we doing it? The weird thing is, when you hear people say, ‘We need to save the planet,’ I think what they’re really talking about is saving ourselves—the planet is going to survive. Humans can die off and the planet will rebound and regrow without us. So, we need to find a balance with nature, somehow. If we use all of our resources, there will be nothing left.

Dorota: In Detroit, and post-industrial cities all over the US, they’re faced with infrastructure issues, like water, for example. Detroit public schools this year shut off all the water in all the schools because there was too much lead and other things in it. And Flint, as you know, was faced with the same issue. So, all those things are something we’re inadvertently pointing t—owe don’t directly call it out, but we’re thinking about these things. What is real value? All those things corporations are selling to us in front of children, in front of people, to get more and more things that we don’t really need in society.

Steve: And it feels too much like profit-over-people. Is there a way we can reposition everything where value is more human, instead of a form of money to corporations?

Dorota: And humans overall—we all want to live a very good, healthy life, and maybe there’s a better balance to all of that. So, I think in a playful way, maybe that’s what we’re trying to say.

Steve: Those are the undertones, those are what are embedded. People can look at it and say, 'Oh that’s a pretty object,' or they can think about the deeper hidden meanings behind it. So, for this new project we really moved into sculptural installation and we love it, and I’ve been starting to think about it, and I feel like there’s a bit of surrealism in the work, as well. Somebody was asking what our style is, and the only thing we could really come up with was ‘dystopian glamor.’ There’s this bit of futurism that’s in the work, but it’s more of like a dystopian society.

It’s almost sci-fi.

Steve: Exactly. There’s a bit of sci-fi in there—these animal people walking around. We were thinking about augmentations of reality a bit. You stumble upon the sculptures and you feel like you could be in this alternate reality. You build the tension between that glamor and this dystopia—it’s this weird thing, the layers of meaning. It’s something so beautiful, but it’s beautiful because it’s sparkly. Why do we find sparkly things beautiful? Is that an inherently human thing? Or is that something that’s been programmed by society?

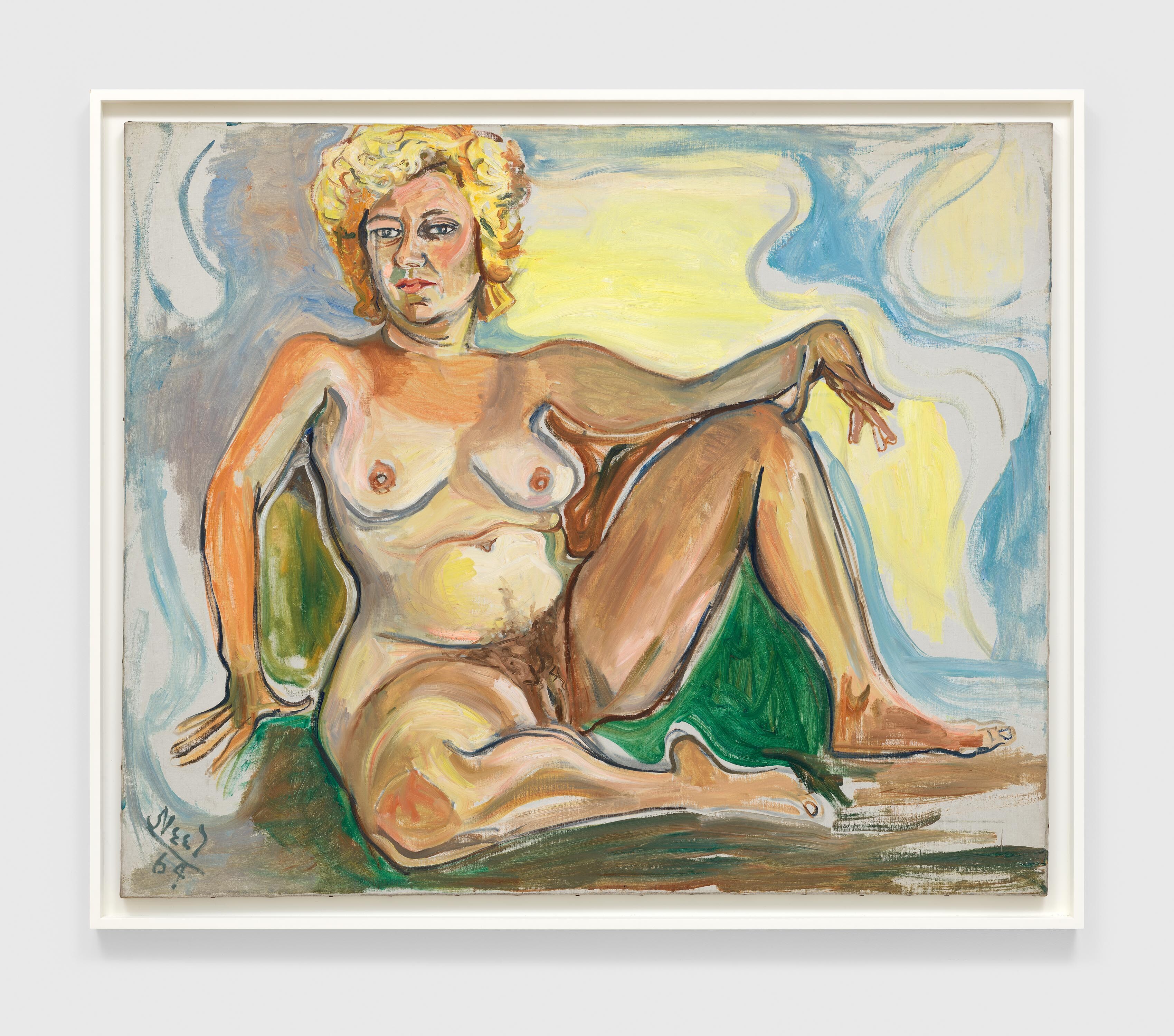

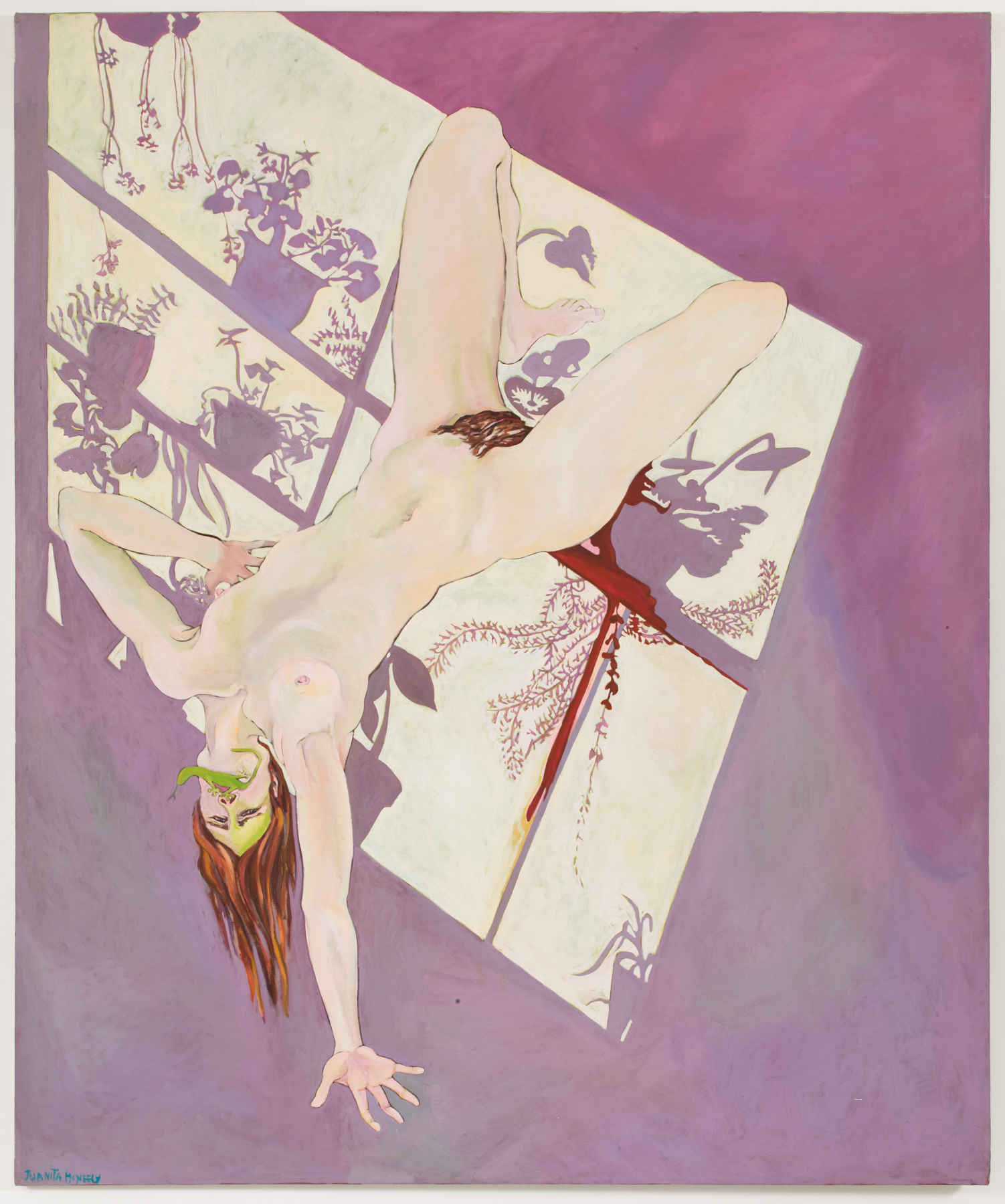

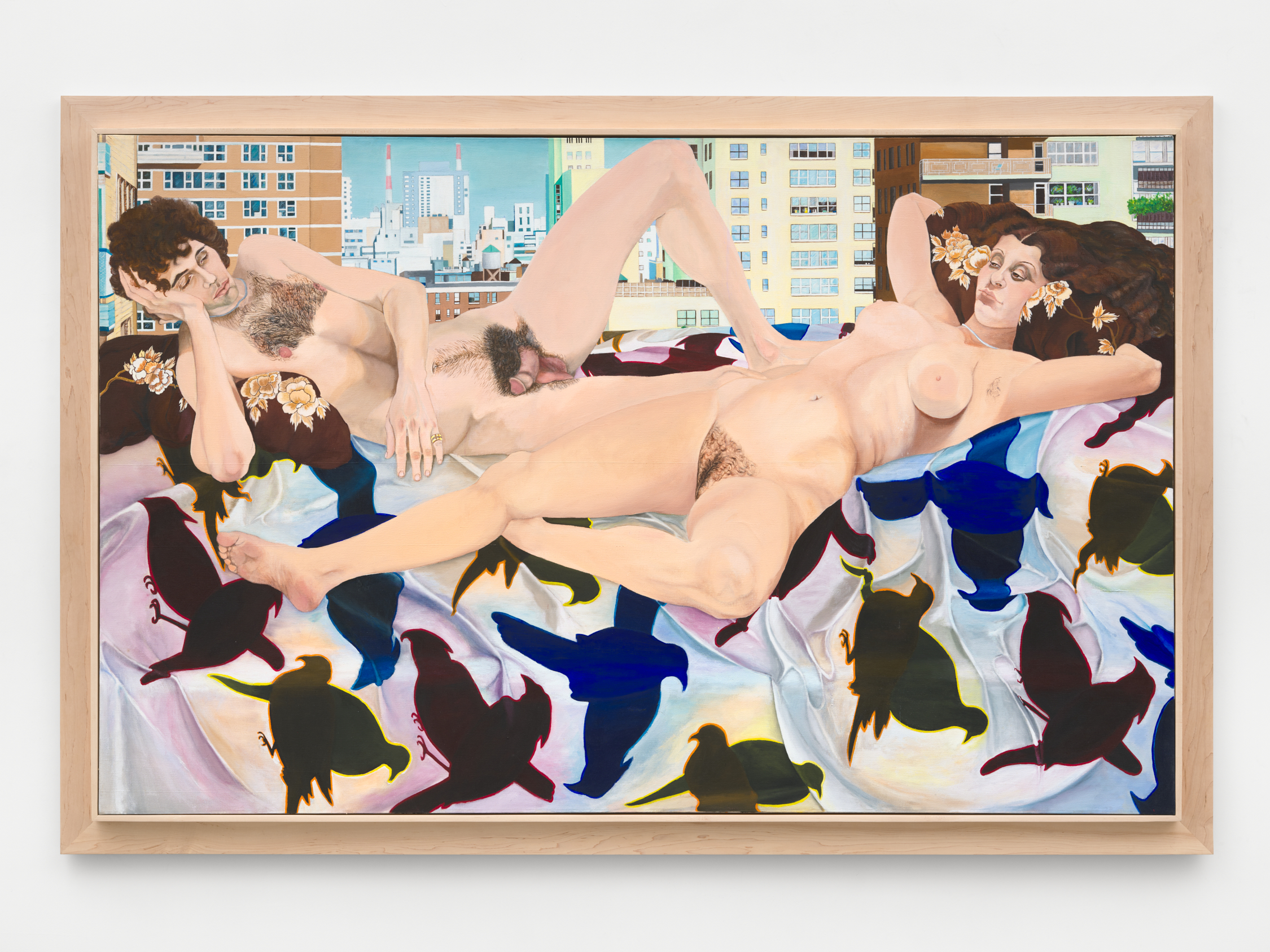

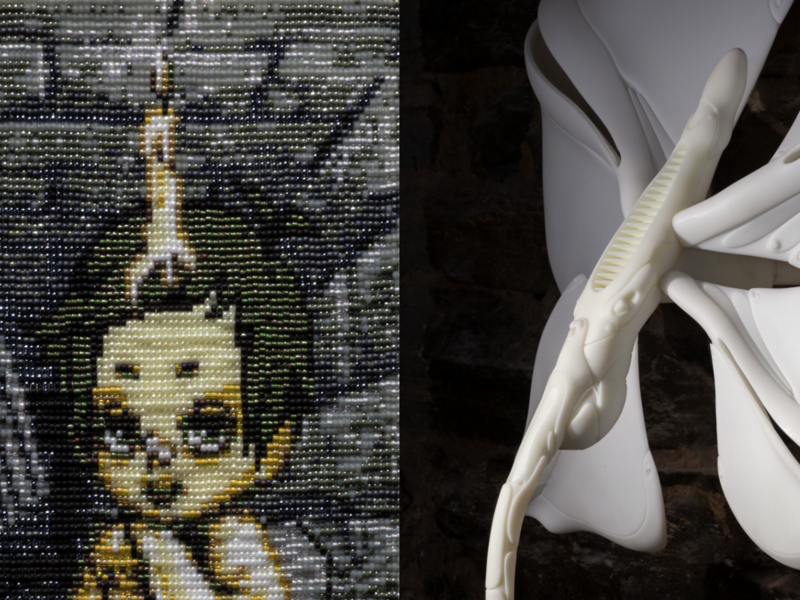

Above: 'Spirit of the Forest' and 'Limited Edition,' all photos by Jon Deboer.

'Value Proposition' by Hygienic Dress League will be open to the public from October 18 through October 21, 2018, from 6PM to 10PM in Detroit. Register here.