Hey, It's Bunmi!

We sat down and spoke about ideas for the future and where he sees his work in the conversation of art and global cultures.

How do you define “culture"? Tell me about the cultural impact you see your work having on those who experience and interact with it.

I think the current global culture is a globalized American culture. When you look at apps, brands, celebrities, music, film, etc, the most popular ones tend to be American. China also plays a big role in the production of that “American Culture,” and in turn, both have a codependency when it comes to maintaining this beast called capitalism. It's with that background that I then think of “culture” in its contemporary understanding, as being synonymous with “Blackness.” More specifically, Blackness in America. In that same vein, if American culture has become the dominant culture and within that, Black American culture has become the most popular, then it's really just “Black Culture” that's the global culture. It becomes difficult for me, because with the advent of Black Culture, there is this demonization of these same things being idolized. I think about the ownership and value of tropes like Jordans, Popeyes, Hot Cheetos, Fashion Nova, Colt 45’s, a lot of these things aren't respected in the same way I see my blackness, yet they hold a social currency in this contemporary culture. I remember seeing a white guy walk out of a Popeyes near my old studio in downtown Brooklyn. Based on his accent and how he looked, I could tell he was a tourist from somewhere in Europe. I remember thinking, “what the hell is he doing eating Popeyes,” assuming that maybe Nathan's next door or McDonald's would be the more appropriate establishments for a european tourist in America to eat at. I am still trying to figure out why, you know, why or where that feeling comes from, that feeling of ownership. This notion of black culture being subjected to capitalist structure is a theme I’m continuing to explore.

If you had to localize it, where do you think the root of this understanding lies?

I think it's a symptom of trauma, it's a symptom of, “they’re always taking our shit.” Take Rock and Roll for example. It’s the fear of having these “products” that have an intrinsic cultural value off their proximity to black people, stolen and co-opted by white people in a way where they monetize.

Do those moments of immediate recognition and frustration regarding that ownership as it relates to “the other” make you upset, or is it just something that you realize and then later disregard as maybe being irrational or misguided?

It's interesting, because for me, Popeye's is terrible for you. It will literally kill you. And it's like, “Is that the thing that I want to champion?” I believe there is a cultural significance and value that Popeye’s holds, but I don't think that those things are necessarily worth holding onto. I don't want a fast food franchise that's not even black owned to validate my blackness or my black experience. This plays into ideas we grew up with, where if you're eating vegan or vegetarian, it's some white shit. Even now that I'm making this art, I'm like, “okay, okay, Durags are obviously black,” but how? And that shit makes me sound crazy, but when I really think about it, they're actually American, you know? And so, if the Durag is black and we don't see them in other regions of the world where there are black people, then I think it would be more justifiable to say that they're American, and Americans just happen to be black. I don't know if that's a controversial position to have as a black person but I also know the discourse on what makes something black or not is also very complex and ongoing and it's not something that's just black and white. Everyone experiences blackness differently.

We met in (2015) when you were working on your very first art piece, Target Practice. In that piece, you placed the heads of men of color on our college campus onto shooting targets and included audio where they spoke about their Black experience in America. How has your work and approach developed since then?

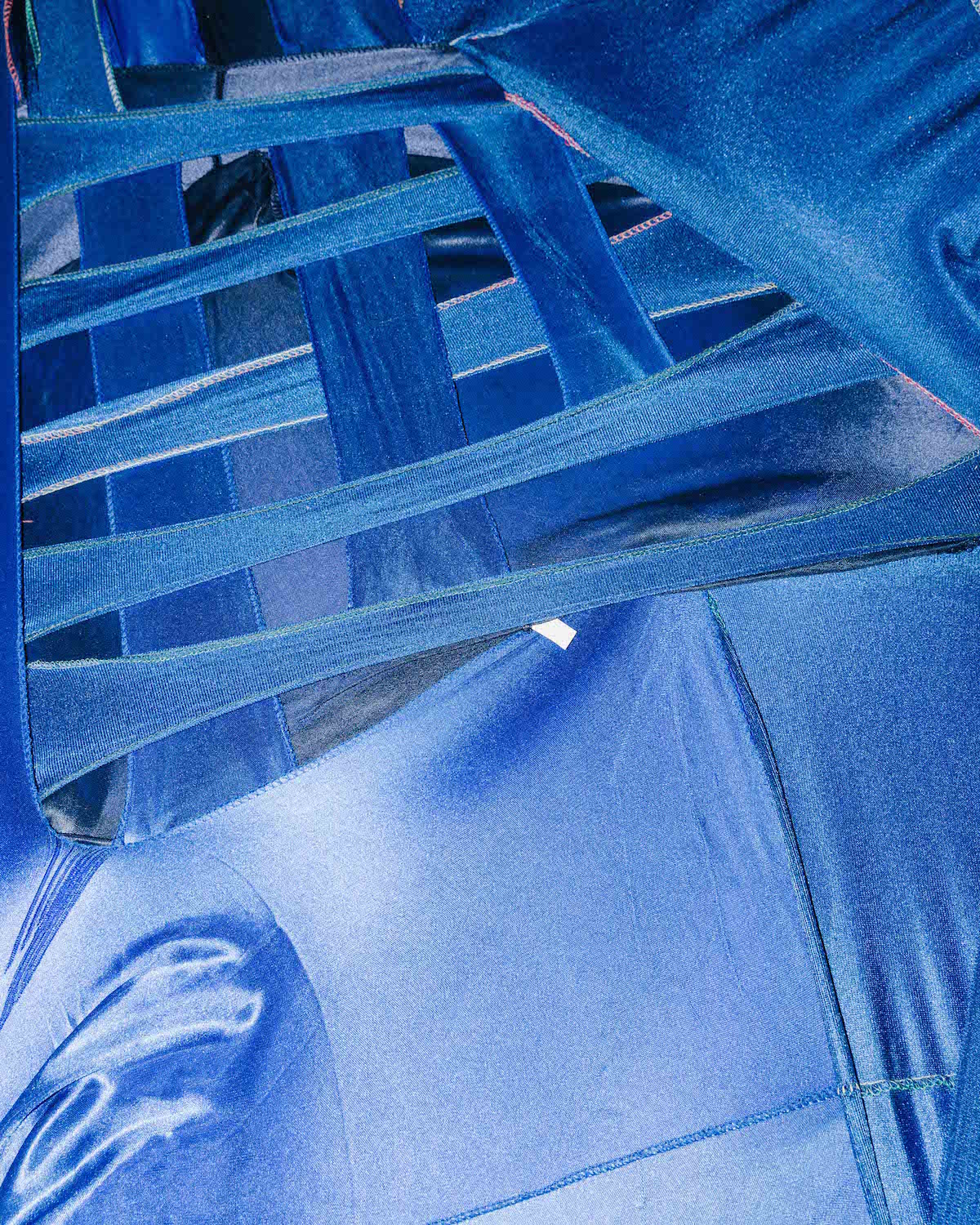

I’m expressing some of the same sentiments as I did with the piece Target Practice, but now, as I've developed my visual language, there has become a more subversive way for me to write palatably. There are a lot of white people that see the work, and I know they don’t look at it in the same way a black person would, which is fine because that's specifically why I use the Durags. However, I find myself having to explain to them why I'm using the material. And while it does defeat the purpose, I believe there is a silver lining in being able to educate non-blacks on what a Durag is, so they can understand there's a function and history beyond the crass perception of them “being scary” (somebody really told me that once). It's important to understand the history of the object and how that relates to conversations around accessibility and respectability. It's funny because the Durag was originally created to make you look less threatening and now it's the flip. I want viewing my work to become a spiritual experience outside of the basic, “Okay we get what you're doing,” because Durags are usually seen like this and you've made them look like art, and now they’re “okay” or “this makes sense.” I have Black people talking about their moms, and the hot comb, and matching their shoes, and the nigga they used to work with and “Oh, I actually have this Durag” or “Oh shit, silkies.” It’s like a portal, I feel like black people can walk into my work.

I love that. How do you feel about the lineage of the Durag? Black people have always worn du-rags, but from what I can remember, when I got my first durag in ‘02/’03, there have been so many developments in color, texture, and overall style. Back then, silkies weren’t even a thing and it's just become this super item. Durags are even more “fashion” now.

I think a big part of that is consideration, that evolution also relates to my practice in a very immediate way. When you look at the paintings, you'll see the seam is on the outside and then the Made in China tag is also on the outside, exposed. Durags aren't usually worn with the seam on the inside, because it’ll leave that line on your head. So to see that tags are now being sewn the way they'd sew a t-shirt, where you have the tag hidden, but the seam is still on the outside, shows this consideration of culture. It is nice to see all the new brands, colors and textures. I remember when Durags were just black and maybe you would see a white one once in a while. Now you got violet and turquoise and orange and burgundy. I like walking outside and seeing all the different color Durags I can spot in a day, it’s inspiring.

How has this development in Durags and their cultural status influenced you as an artist? The pieces have ripened so much since you first started working with them as a medium.

I don't usually create a series of work, well at least I wasn't doing it before. I like to make things and move on to the next. All of the works I made prior were all so different from one another. One might be a sculpture, the other might be a video, maybe I’d make a painting or try to figure out a performance somewhere. I still work in that way, but over the past couple years I've felt motivated to continue exploring these Durag paintings and it's kinda hard to stop. Especially when you go to the beauty supply store and they got new colors and patterns you are just seeing for the first time. It's like going to Blick and seeing new paints you haven't used yet or a music producer using a new drum kit. It's exciting to be working with a medium that is constantly evolving and developing. I couldn't have made this work 10 years ago, the variety just wasn't there.

With the Black Lives Matter movement in powerful effect, the legitimacy of how museums, galleries, and other art spaces acquired Black art throughout history continues to be scrutinized. As an artist and a Black man, how do you navigate a desire to be a part of the “art world,” in addition to being aware of the methods in which these art institutions came to be in possession of the Black art in their collections?

I enjoy being around the “Art World” but only for certain moments and from a distance. That environment is fickle and if you don't guard yourself, you can really get caught up.There is a long history of artists being exploited, especially now with this whole “Black Art” boom, it's hard to really feel like people are genuine in their motives. I’ve been much better at vetting people before I give them my time. To be honest, I prefer showing my work in an institutional setting if it's physical objects, and if it's something else, I like just putting it out in the world on my own. I believe it becomes less susceptible to art world politics that way, because if I am going to be a part of those politics, I want it to be on my terms.

You had a show that opened just before COVID-19 hit, at the Museum of Art & Design, and then a solo show that was supposed to happen in April. What can we look forward to as the world opens back up, and what are you looking to explore in your work and approach following these pending exhibits?

Yeah, the title of the show was LOCAL IMPORT, that's really the last thing I remember doing before the lockdown. I am glad people were able to see it before everything closed. I'm currently working on two solo exhibitions I have coming up early 2021, one at the John Kohler Art Center and the other at False Flag Gallery, which also happens to be my NYC debut. Both shows will run at the same time. I feel like I've just been mining more and more information and trying to make sense of it through the work, hopefully I can continue to concentrate these ideas in a way that I feel might be digestible to my audience. I don't really know what that looks like at this time, but it's definitely just the evolved version of themes and ideas I’ve already been playing with over the past couple of years.