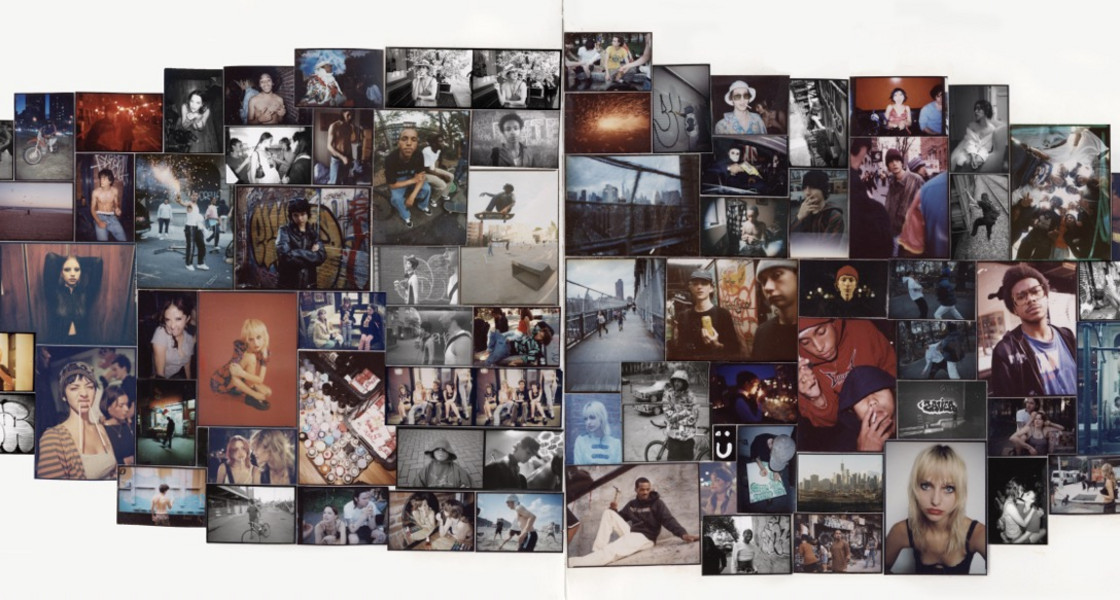

The Holy Third Gender

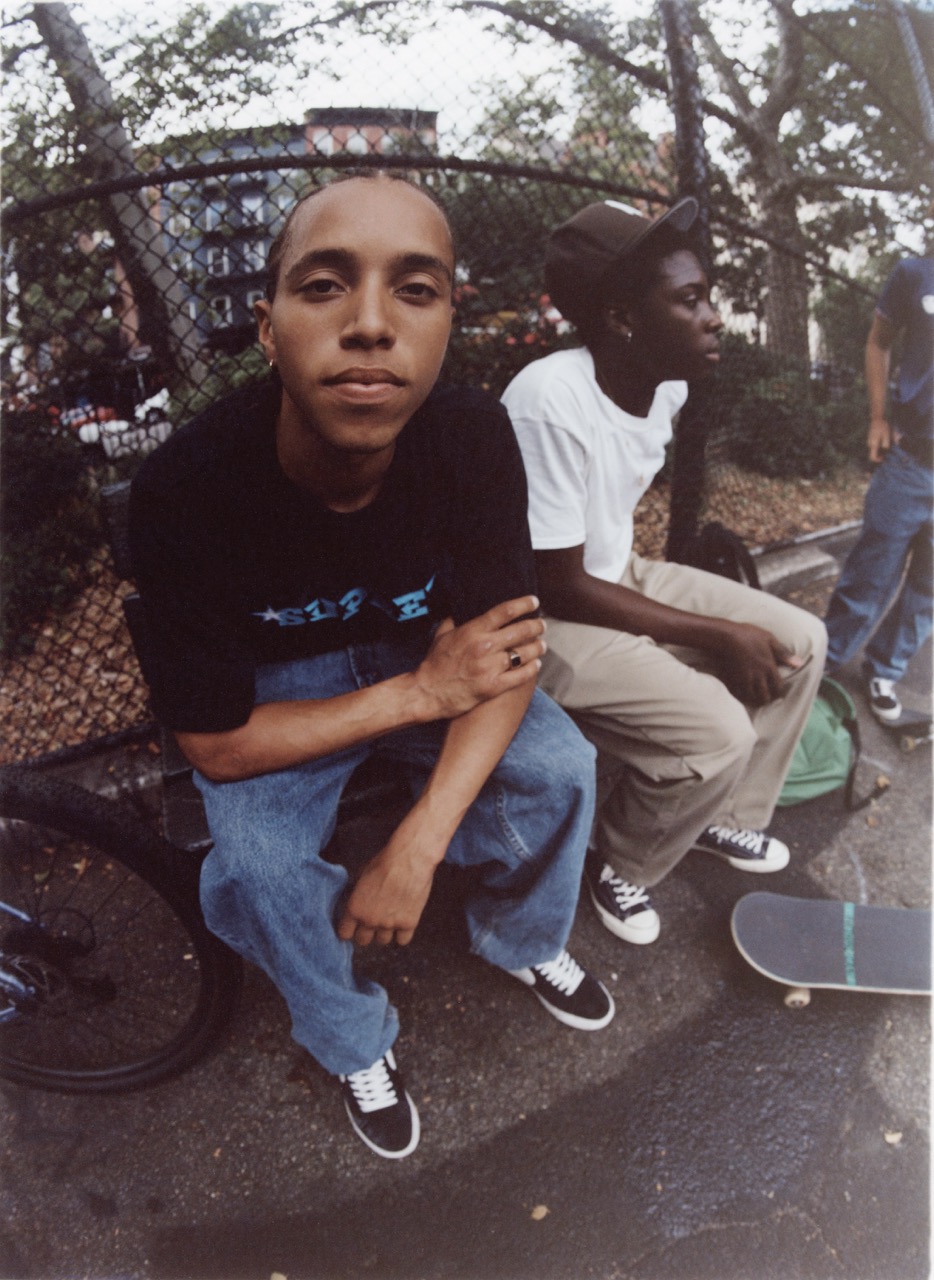

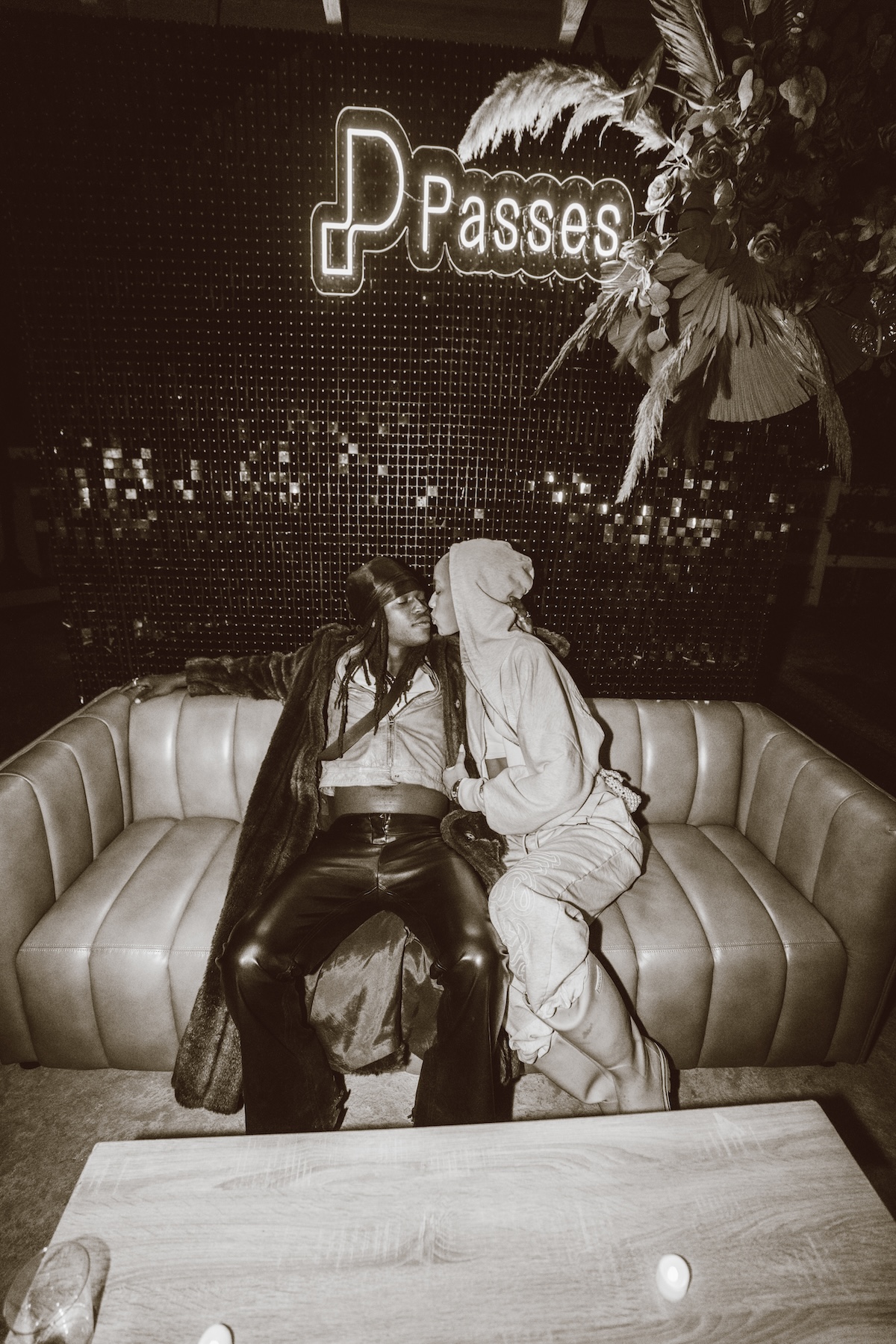

Lead image — Shalu, Manisha, Rishika, 2020. C-Print Fujicrystal mat. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Ziccarelli's new exhibition at New York's Perrotin Galerie, titled 'The Holy Third Gender: Kinnar Sadhu,' is a series of portraits and video confronting the compelling history and current situations of these Kinnar Sadhus. Elusive French artist and activist JR sat down with Guillaume to discuss the exhibit and his personal connection to India and its people, especially the beloved Kinnars.

How did you discover the situation in India for transgender people?

I have some close transgender friends, and have worked on a few different photography projects around portraits of transgender people since the early 2000’s. They have real resilience and beauty, and taught me what it means to stay true to your own identity, even when faced with tough outside pressure. The trans friends I knew before going to India were mostly in France, the U.S., Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia, and I wanted them to see what I had discovered in India.

Since 2008 I’d been really interested in this massive Indian festival where 100 million people gather. And then I heard that the Kinnar Sadhus, who I call the Holy Third Gender in the exhibition, were making history, because they were allowed to officially take part in these festivals. It was all over the news how they’d been formally accepted as a group into this ancient religious ritual, with a kind of status they hadn’t had before. [They had participated in one previous Kumbh Mela, but they did it more on their own, without the same recognition, and some of the privileges you get with that recognition.] I was impressed that an age-old tradition would open up to this community like that, and I wanted more people to see it, learn about it. I know trans people also struggle in India for equality and respect, but this was one important step toward progress.

Tell me about this festival that takes place every 12 years.

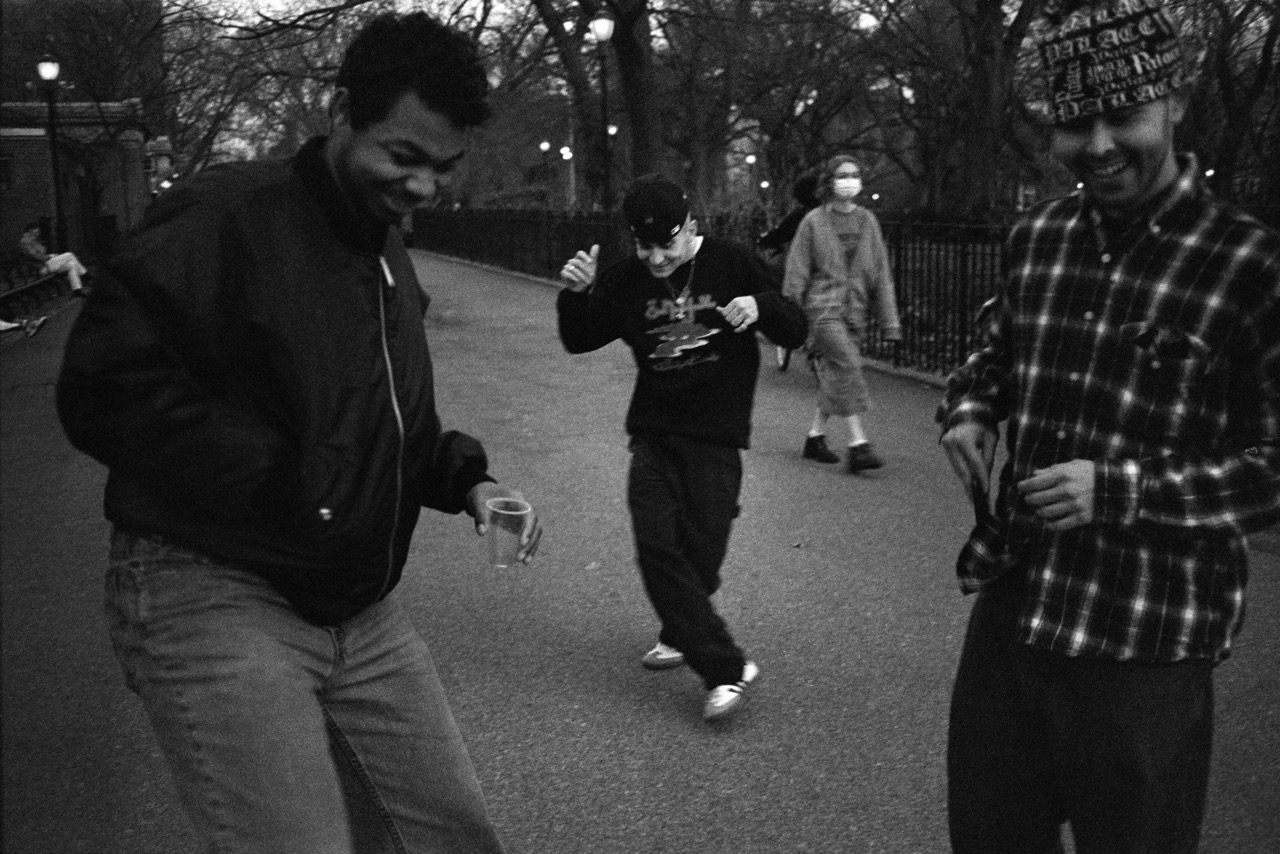

It is a bit more complicated than saying every 12 years…It happens in a few different towns, depending on the year and moon cycle. There are also some half festivals. I’m really not the best expert on it, and prefer letting you know what I felt and learned. When I heard that over 100 million people attend the festival, I told myself I had to experience what that energy was like. Of course, all those people don’t come at one time. It’s spread over a 2-month period, but you still have about 4 to 6 million people there at any single moment, which is why the Kumbh Mela is called the largest human gathering in the world, along with Mecca. Whole temporary cities must be built to accommodate them, with roads, bridges, temples, shops, restaurants, campgrounds – all from scratch, built on top of a no-man’s land of sandy, rocky, and wet earth.

And the other important thing to know, is that pilgrims come to the festival to cleanse their sins in the Ganga River. I really wanted to see all those people experiencing the joy of washing away their sins in the water.

Was this your first time in India?

No I have been to India 5 times. The first time was the most important one. I was 18 years old, and you don’t ever forget your first visit to India. India changes everyone who really sees it. If you’re curious, India gives you a lot to think about, and learn from. The people, religions, traditions, colors, how people live. India is an explosion of energy and culture.

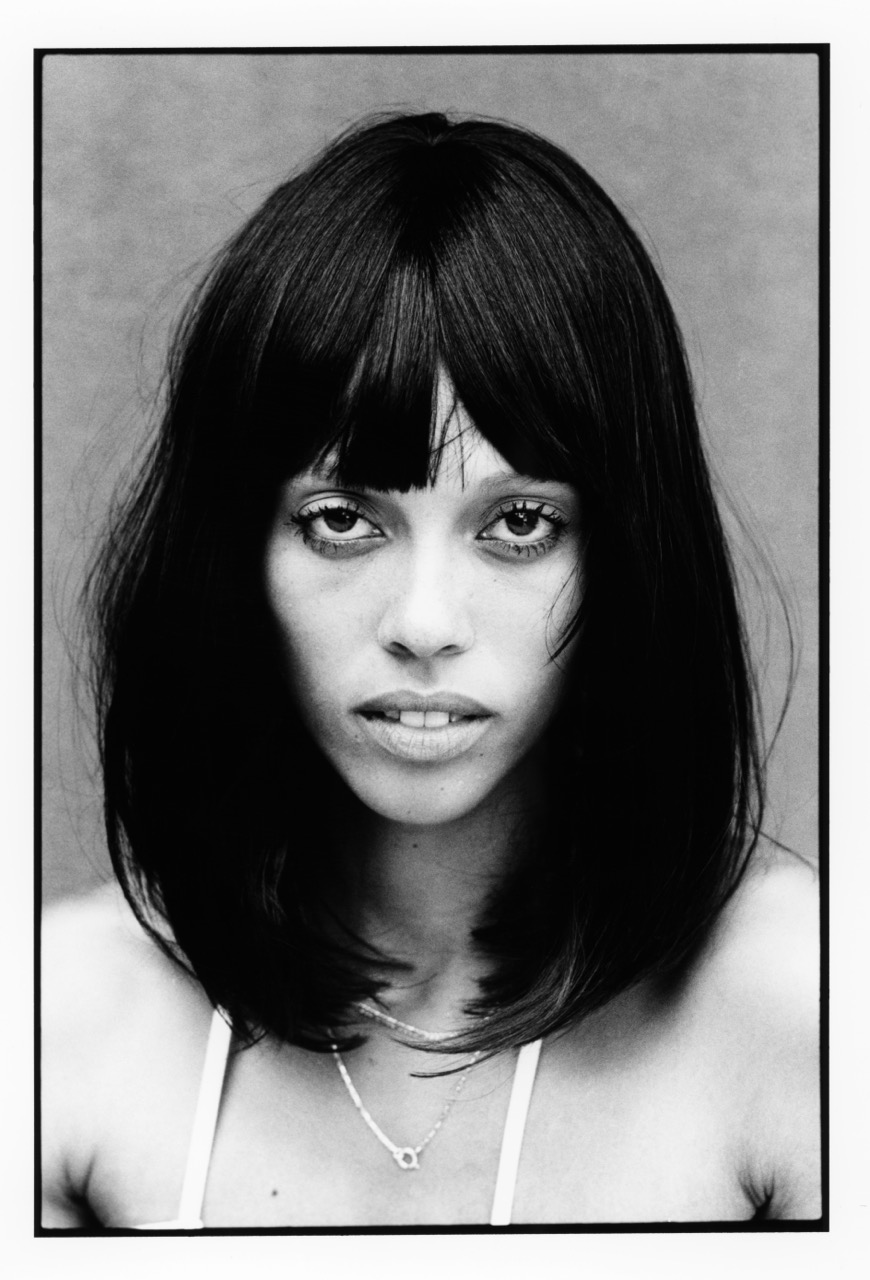

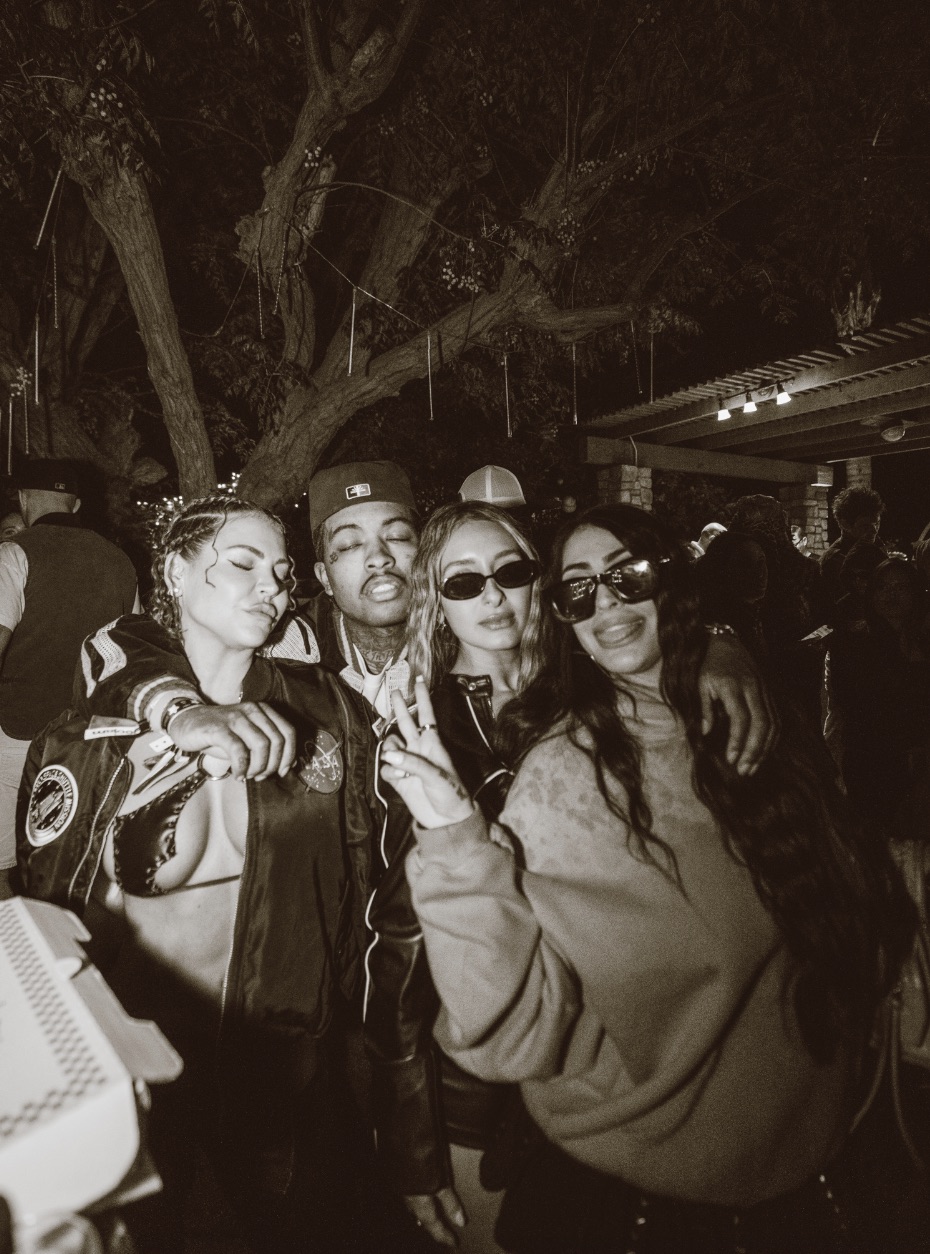

Left — Manisha, 2020. Digital pigment print. 90 x 60 cm | 35 7/16 x 23 5/8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Right — Rishika, 2020. Digital pigment print. 90 x 60 cm | 35 7/16 x 23 5/8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

What are the challenges of working in India?

I’ve actually had less difficulty working in India than in many other countries. First of all, their English can be better than mine, and creating connections and making new contacts happens very quickly there. Plus, they put a massive amount of energy into projects they are involved in.

The challenges I’ve had have been around the number of people, and the dense population there. The waits and lines are long, but I can pretty easily start to forget about that. So when it can take 40 hours for a bus to drive you on a 200km trip, it starts to feel long. But you learn a new kind of patience. Plus, you’re also a bit more free, in a way – on those long trips you’re allowed to sit on the roof of the bus [I know it may not be the safest]. Once I got to watch the Himalayan Mountains passing by from the bus rooftop. It felt like a kind of magical, real-life movie. When you take France’s high-speed TGV trains, you have no clue what is happening outside, between going from A to B.

Have you done a series of portraits before?

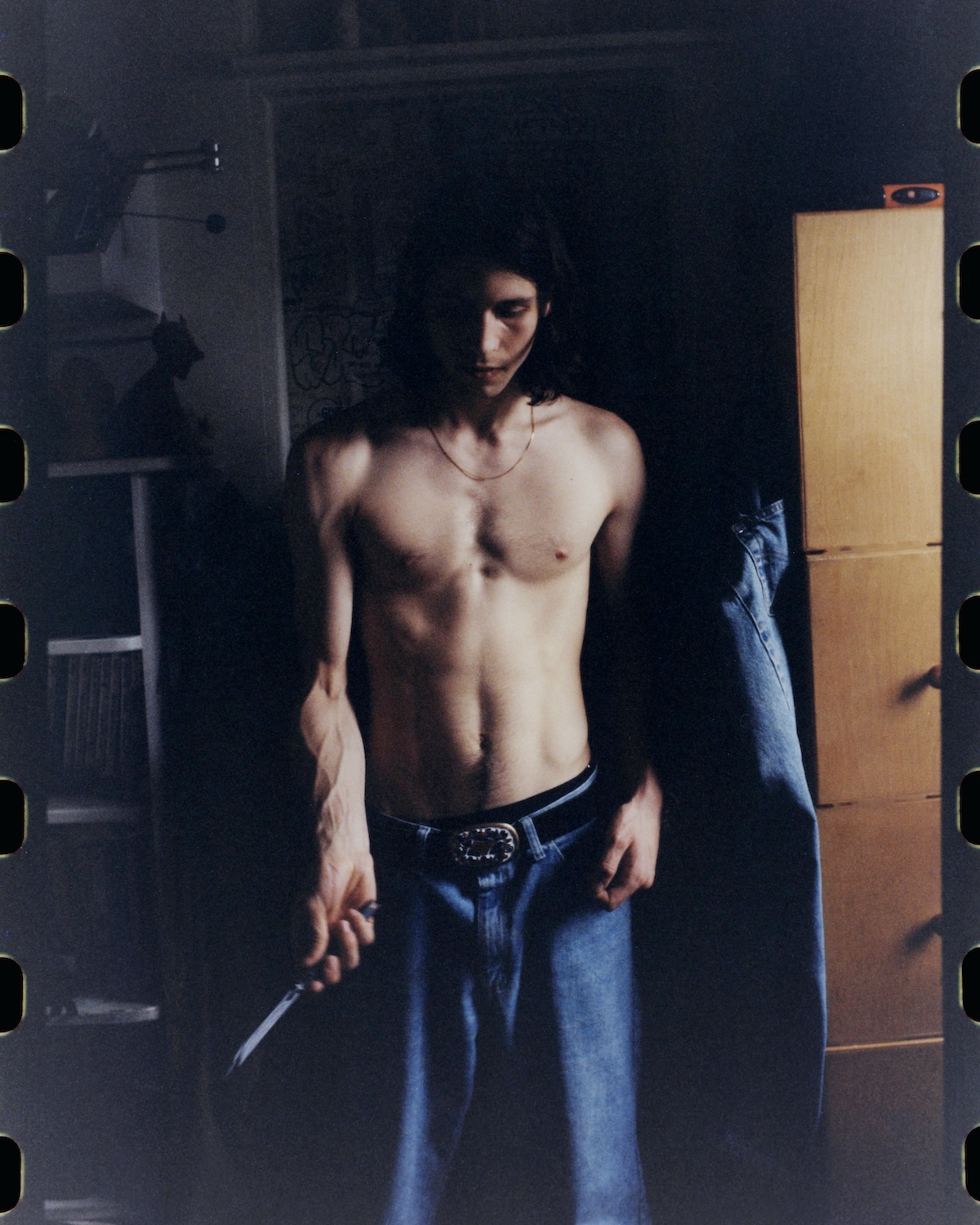

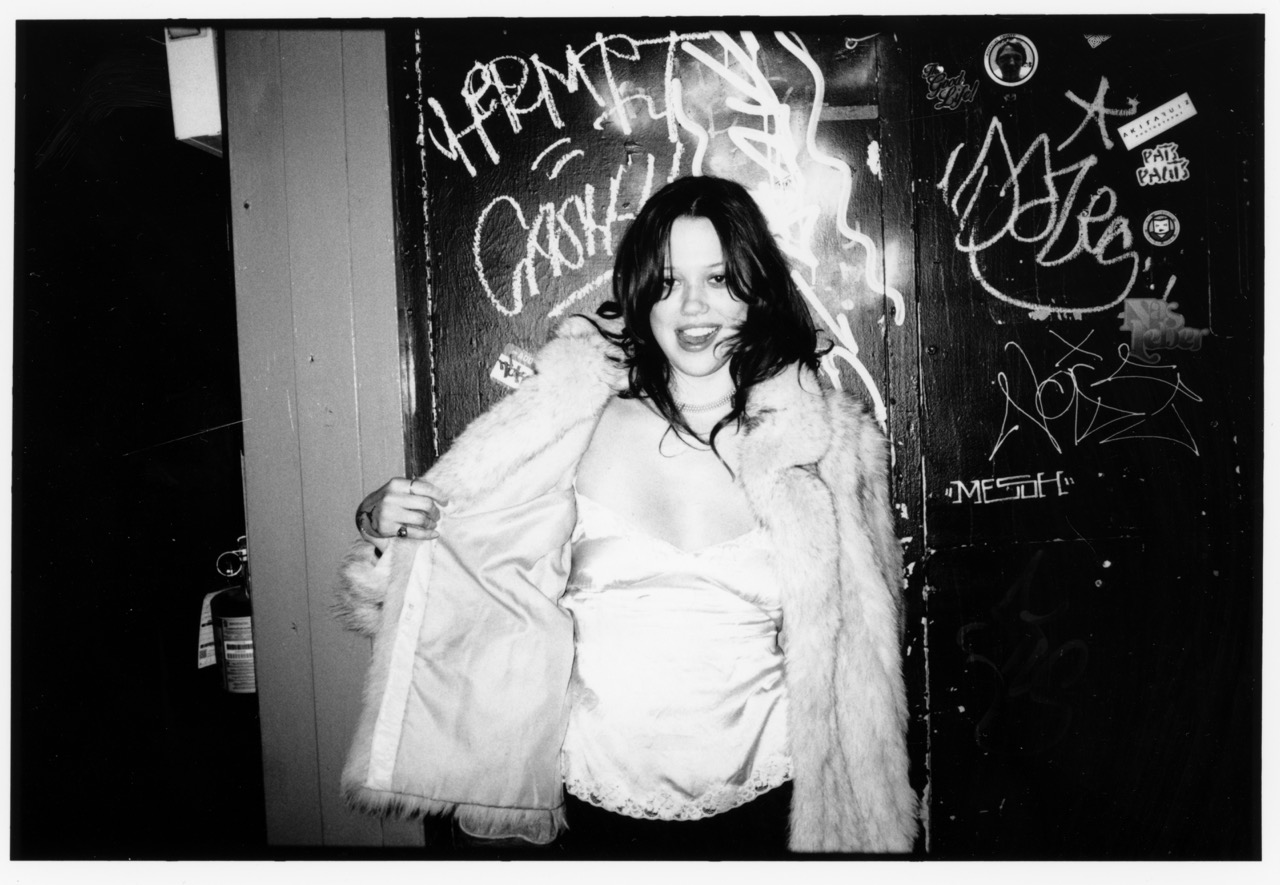

Yes. My first published series of portraits, which I worked on the early to mid-2000’s, was called the House of Love. I shot it in the MDT in Paris, an apartment with a bar on the ground level, which actually acted as a cover for the parties that went on upstairs and in the basement. Upstairs there was another bar, a lounge, a stage, karaoke, and a pole for shows. Nothing was ever planned, and the stage belonged to anyone who wanted to perform. It was a place for live, hot, kinky sex in full effect. Bodies, heat and pleasure.

I shot portraits in the MDT, but also in the homes of the transgender regulars who came to this underground kind of club. I wanted to see them outside the party context too, around their personal belongings, and in their everyday lives.

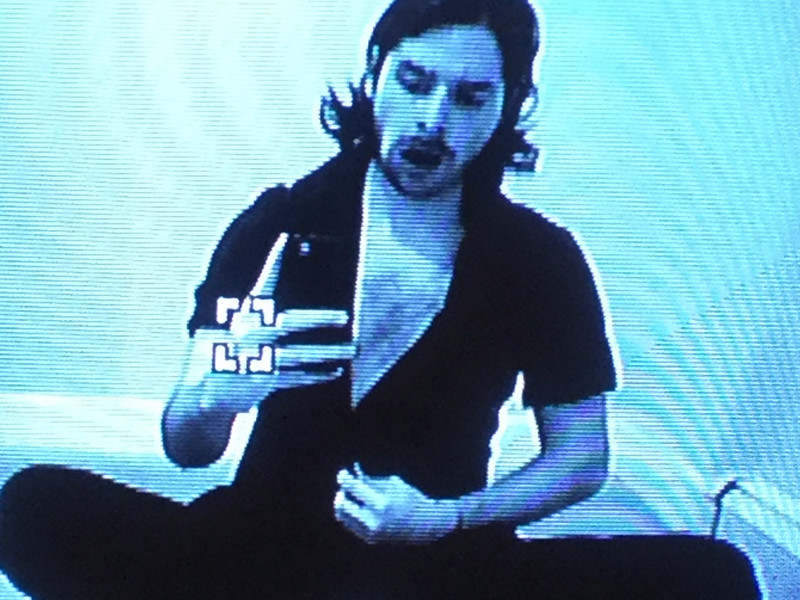

Kinnar Alter, 2020. C-Print Fujicrystal mat. 40 x 60 cm | 15 3⁄4 x 23 5/8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

How do you get your subjects to accept being photographed?

The first thing I hope for, is a kind of flow, a kind of electricity that passes between me and the person. And if that happens, I try to make friends. I always try to take my time, because it ends up making all the difference when you eventually do start shooting. I spent 2 to 3 days with the Kinnar Sadhus without any equipment when we first were getting to know each other.

I can’t take a portrait without having a chat, and having the person understand what the project is about, and where I’m coming from, and what I’m trying to do. Of course I also need to better understand who they are, how they talk and express themselves, how they react to what’s around them. Then I can think about where to place the lens.

Have you stayed in touch with them?

Yes, of course. I’m in touch with about 15 Kinnars Sadhus, but I talk regularly to 3 or 4 of them, that I’m closer to.

In what cities do Kinnars mostly live?

They are spread all over India, randomly, I’d say. They join up for the festival under the same temple, but then they return to different parts of India.

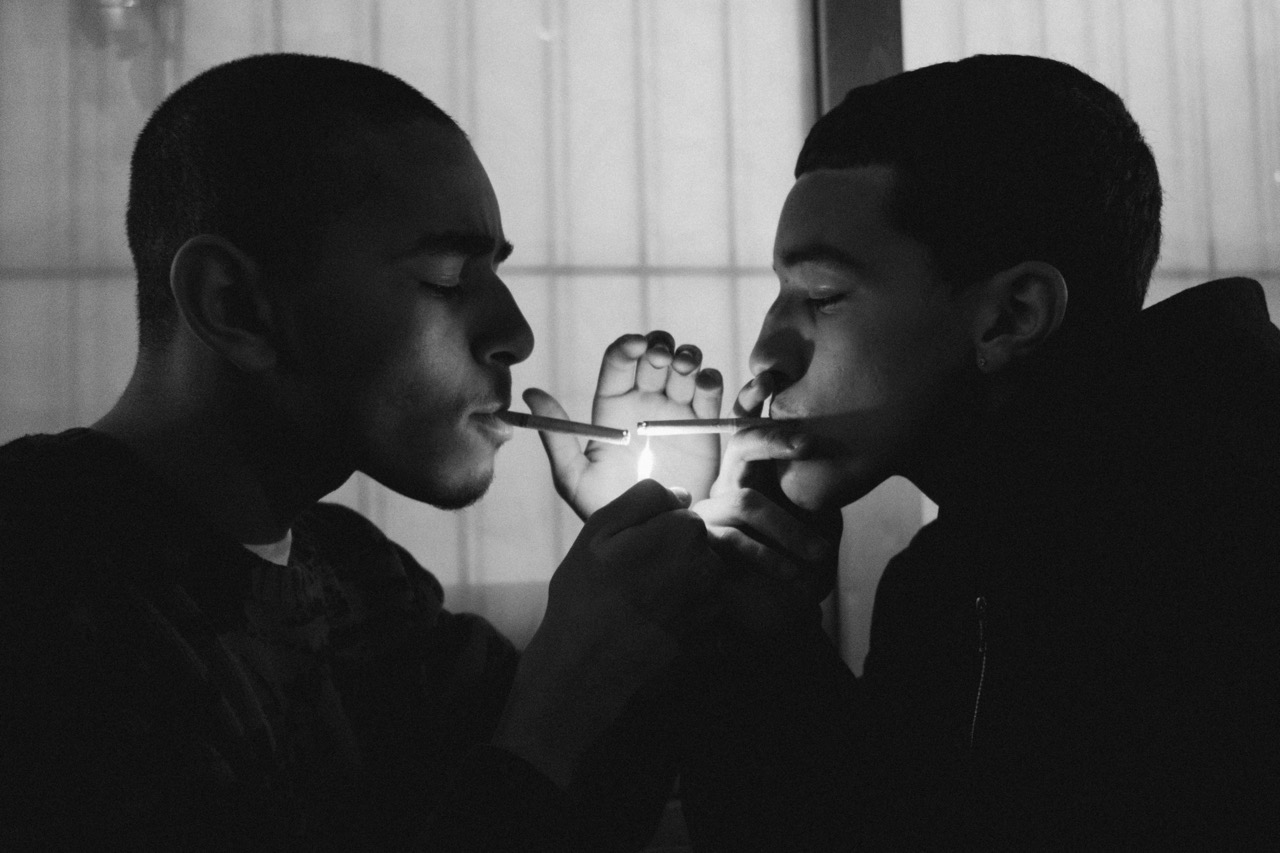

What is the difference for you, between photojournalism, and an artistic project?

I think documentary photography and photojournalism can cross over into art, and the reverse is also true. The video in the show feels more like a documentary piece to me, whereas the photographs reflect a more artistic project and perspective. I wasn’t shooting images for the news. I wanted to show who these people were, something from inside of them. I don’t think you can always allow yourself to do that when you’re trying to report on what is happening for the news. With these portraits, I was actually thinking of my photographs as a kind of version of religious iconographic art, where I try to show these women almost like goddesses – which is how I saw them. So I’m showing a perspective, and for me, something of their inner soul, so that others might feel or connect to what they see there. To me art is one good way to express that, versus photographic reporting, which is more about saying: this happened here at this time, and it’s a fact.

During this unprecedented period where people are protesting for Trans Black Lives Matter, what can New Yorkers learn from the Kinnars?

I hope these portraits and the video, can add another piece to the protests, by showing how another culture is handling this. The Kinnars fought and succeeded in getting a legal status for the third gender in 2014. So on their passports it states that they are third gender individuals, and this makes them eligible for affirmative action types of aid. The Kinnar Sadhus in particular have had to push to get recognition of their religious group, and they spoke to me a lot about wanting equal opportunities to work like everyone else.

So to answer your question, I think the idea here is that trans communities are fighting everywhere for more acceptance and equality, and seeing that, and seeing where they’ve succeeded, and where and how they are still being held down, is important for everyone – whether you feel part of the LGBTQIA+ community, or not. We all need to know more about what is going on outside our own, smaller worlds.

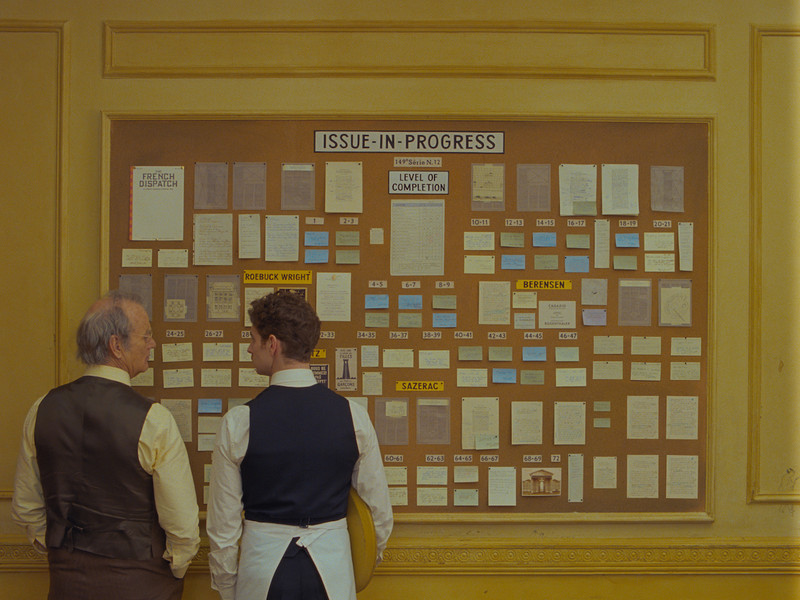

Left — Shalu, 2020. Digital pigment print. 90 x 60 cm | 35 7/16 x 23 5/8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

Right — Prachal, 2020. Digital pigment print. 90 x 60 cm | 35 7/16 x 23 5/8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin.

What is it like to have your first solo exhibition at Perrotin gallery, where you have worked for years, typically helping other artists exhibit their work?

First of all, I am very honored to exhibit in such an important gallery. I feel thankful to Emmanuel, and to Peggy, the gallery’s New York executive director.

Yes, it’s definitely a switch to go from taking photographs and videos of exhibiting artists, and producing their shows. In a way, that goes back to what you were asking about the division between art, and photojournalism or documentary. Categories don’t matter all that much, in the end.

But yes, getting the chance to show my work was amazing news to get right in the middle of lockdown, when things had been looking pretty dark. For me this has been a huge opportunity that I take very seriously. I didn’t want the gallery to be let down, and I wanted to create a show that Emmanuel would be proud of. And after years of working for him, I gained experience that helped me make this show happen, big time. Over the years I’ve learned how to select and present work, and I could use that experience with my own show.

There were challenges to working during the lockdown, but you know all about that! When I started at the gallery, there was only one exhibition space, and maybe 10 or 12 staff. Now there are 9 galleries around the world. So I did a lot of different jobs for the gallery, since I was there in the early days, and I was exposed to a lot of new and different tasks, so I could use all that when I put up my own show. And yes, it’s not the same to work on your own show, versus another artist’s. So I’m very happy.

Who are some photographers or artists who inspire you?

Catherine Opie. Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Nobuyoshi Araki. Lee Friedlander. Garry Winogrand. AND OF COURSE, YOU!