By the Light of the Moon

Marine grew up in Brive-la-Gaillarde, about a five-hour drive south of Paris. Hers was a fairly typical suburban French childhood, modestly pleasant, and filled with physical activity. Her father was “really something like a sports addict,” she recalls. “He was playing tennis, football, running—he could not sit down for five minutes.” Marine took after her father, and from a very young age focused her attention on tennis, which toughened her up and gave her the foundations of a serious work ethic. “I was living in this small town, and after school every night I was going to play tennis, and then also on the weekends, and on Sunday I was doing a physical training course, just like a boy.” In addition to physical rigor, the unique elements of tennis in particular exposed Marine to some fairly mature concepts—composure under pressure, self-reliance, resilience—at what would normally have been a very tender age. “When you’re ten years old playing with a 55-year-old woman, playing tennis by yourself, then you have to keep your sangfroid. It’s quite a hard sport, because you are really alone also, so it’s not always nice. But I also liked the team spirit around it, and training all together. I think it trains you to a certain pain, a little bit, because as a child, you are thirteen, you go on a Sunday, you’re doing training, it’s like six degrees, you are fucking cold, so... Yeah, for sure, it helps you have some courage.”

As she continued to grow, another aspect of Marine’s personality materialized. From within the rough-and-tumble tomboy emerged a girl with an affinity for style, especially as a means of expression. “When I try to remember what I liked at the time, I really had a double life. In the evening I was with the boys a lot, jogging, looking really dirty, and then in the day I would dress in pink pants, with a crazy haircut. So I had this double playing already. My mom, she’s not an artist, but she always dresses really nice, at least from my perspective. She likes colors, and without actually knowing about ‘fashion,’ she has something—it’s just something in the air, let’s say.” In addition to her mother, Marine remembers taking certain cues from her grandfather—again, not an artist per se, but a man with the obsessive spirit of a collector, whose craftiness sparked something in Marine, and even had a direct influence on her future designs. “He was a collector of key anchors—my last show I made something like that, a couture piece with key anchors, that was from my grandfather—he collected glasses, collected vinyl, just collecting everything that did not have a lot of value, actually, and making an amazing board of it, really precise. Every five centimeters he would stick a key anchor, even though these things cost ten centimes. But I loved it, and I passed so much time doing that, so maybe something came from this side also. But he was just working in a bar, so it’s not like his job was about that.”

With a precocious drive and hints of her father’s hyperactivity, her mother’s intuitive sense of style, and her grandfather’s hobbyist spirit, Marine set her sights on a new endeavor— art school. She was fortunate to have the full backing of her parents, who saw value in the process of exploration and had already noticed some signs of raw talent in their daughter. “They just were like ‘Yeah, you’re good at it, and you draw super well.’ Because I never drew fashion, but I drew landscapes, nude women, nude men, these things that you learn when you’re starting art. And I was quite good at that! I was not thinking I would do fashion, I just liked color and drawing. So they said ‘OK, well try!’ you know? Because at the time you had to choose whether you wanted to do mathematics, literature, and I was like ‘You know what? Maybe better for me if I learn art, I’ll have more fun.’ So this was a great thing, and a chance I had, because they were super open-minded, even if they did not know exactly where I was going, they were all the time super supportive. They would tell me, ‘OK, if you don’t arrive, you will do something else, don’t worry.’”

So off she went, at the age of 14, to an internat—a sort of academic internship—near Limoges. “I was there every week from Monday to Friday, and I think that gave me a lot of independence. When you leave your parents’ place so young, you have to take care of yourself really early. That helped me know what I want to do more quickly than some children.” The town where she lived was too small to have any major fashion retailers, but she and a friend found a used clothing store, and within a few years Marine had amassed a formidable wardrobe. “It was basically a vintage shop—but for lost people, because no one was ever going there. We were going to this shop every day, buying some yellow belts, some berets, just amazing stuff, and everything cost one Euro so I could afford basically everything I wanted.” Add to that a number of pieces discovered at the brocantes she would frequent with her mother and grandfather, and by the time she was eighteen, Marine reckons she had a closet of almost 500 garments. She made a habit of classifying and organizing them, building little looks out of different combinations. “I started actually experiencing fashion through my own body, seeing all the things that worked with each other, and I would also cut my pants, or start mixing things that did not naturally go together.” Fashion had become a logical career choice, but at that point it was only one facet of Marine’s general desire to create, rather than a singular interest of hers—she says she would have just as soon designed a chair as she would a garment. What attracted her most was the relationship between the human body and the objects and materials we interact with on a physical level, but no matter how she wanted to explore this dynamic, there was still much more to learn.

Marine’s next destination was Marseille, for a technical program, then a brief spell in Antwerp, and finally on to Brussels and the famed La Cambre school of design. Marseille marked a period of maturity as she graduated from her teens, and a time of cultural awakening. Marine extols what she calls the “hybridity” of the city, the diversity of ethnicities and lifestyles intersecting there, and also sees it as an antidote to the prejudices of Paris-centric fashion. “It’s a big city when you come from the countryside like me, and it’s a city where a lot of things happen. It’s really a hybrid city. And also to study fashion in Marseille, it’s not really what you would think is the normal way to make fashion, you know what I mean? Because in France everything is centralized, and if you do good fashion you have to go to Paris, otherwise you are not good enough to go there. So I was a bit like ‘Yeah ok, I don’t care, let’s go here, I’m sure it will be great.’” Her studies in Marseille were more practical than creative, which suited Marine fine, as she wanted “to learn how to build, before how to create.”

At La Cambre, in Brussels, Marine fit in quickly. The city had plenty of the “hybridity” that she had come to appreciate, and the program was highly creative, reinventing the traditional fashion syllabus with a focus on dimension. “Everything was 3D work. The exam was about 3D garments made of tape, so of course I obviously had a lot of fun. What was great at La Cambre was that first, you learn how to do 3D volume, and then, once you know how to do 3D volume, and work with proportion, then you do the pattern. That’s great, because then you are opening the possibilities of fashion. If you start by patterning, then you will stay in your pattern, and you will never create anything new.”

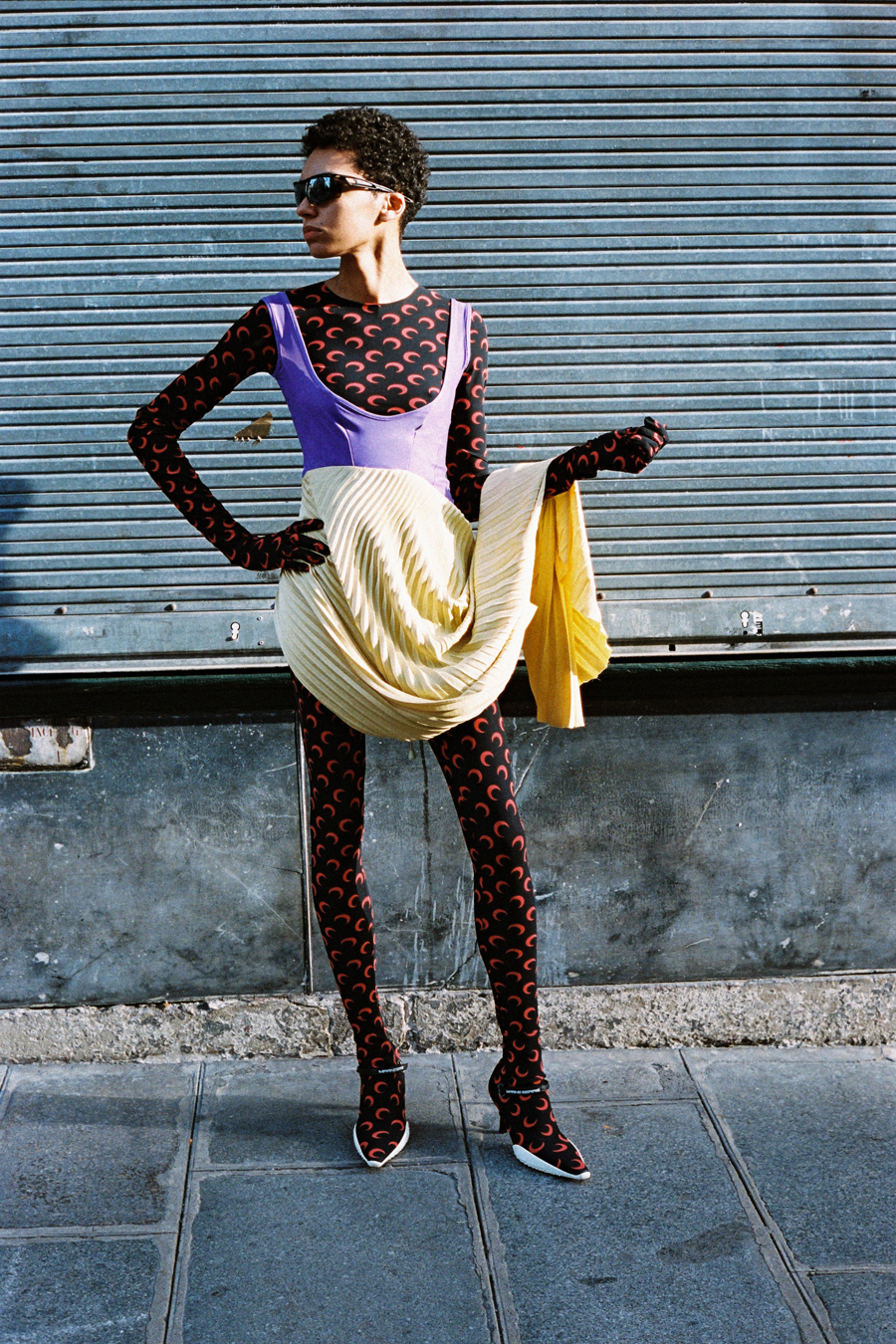

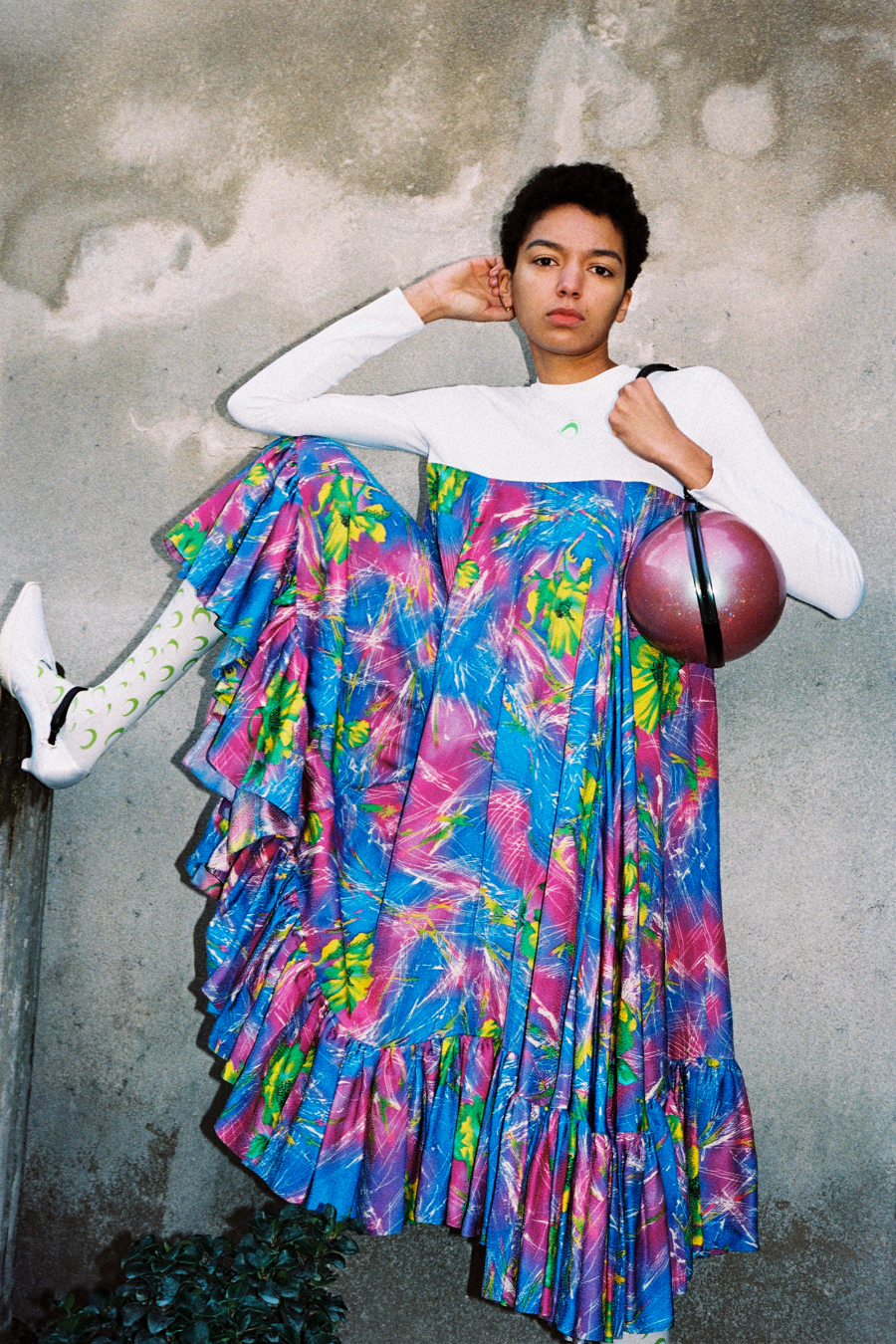

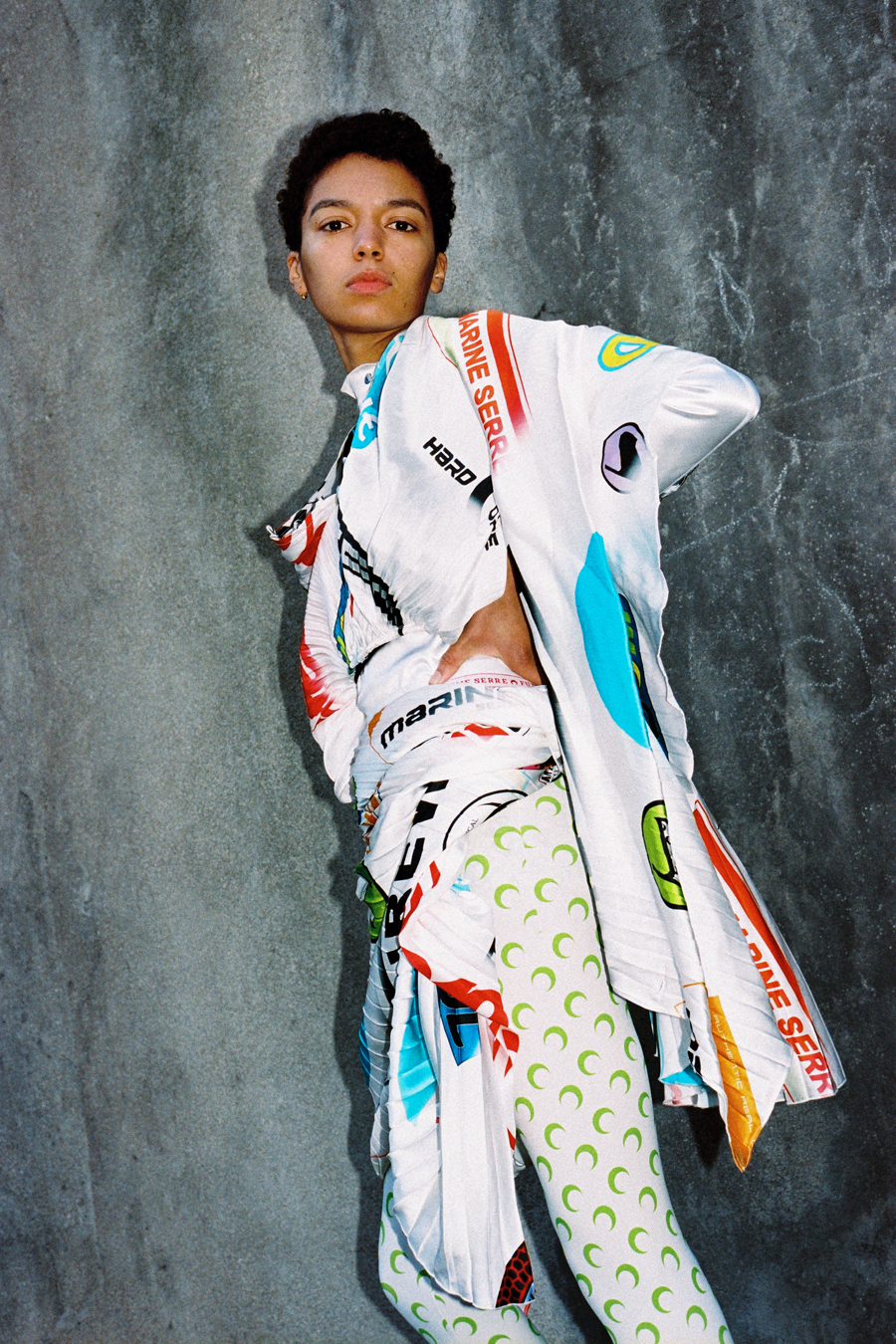

During this time Marine truly came into her own as a fashion designer, developing the technical savvy and creative intuition that would earn her stints at McQueen, Margiela, Dior and Balenciaga. But it was her graduating collection, entitled Radical Call for Love, that would boldly announce her presence to a global audience, captivating everyone from the young enthusiasts to the industry elites. The collection is a celebration of the hybridity Marine continues to find herself so enamored with, combining influences from modern day athletic-wear and traditional Arab garments akin to the hijab. It also managed to combine elaborate construction and dramatic proportions with a surprising degree of comfort and wearability. “You have quite complex pieces in Radical Call for Love, like these huge dresses that can be draped, but at the same time I was always thinking about practicality. So, for example, you have an elastic strap inside the skirt, so when you put the skirt on you strap it on your legs too, so that you can walk properly. It’s almost like a sports detail inside of a super couture dress. So I really like experimenting with new things, to see how to create volume, but at the same time being able to sit, being able to move, being able to live.” The collection also incorporated a symbol, laden with religious connotations, that would soon become closely associated with Marine’s brand—an elegant crescent moon, at times positioned on its own, like a sportswear emblem, on a headpiece or top, at others patterned across the entirety of a sleeve or a high-heeled boot.

Radical Call for Love debuted at a volatile time, especially for those in the French diaspora. Nightmarish attacks had recently been perpetrated in Paris by Islamic terrorists, inflicting a grievous wound on the collective psyche of France and beyond, and stoking Western fears and animosities toward the Muslim world. Many of the attackers were traced to a terrorist cell in Belgium, where Marine had been studying. While she doesn’t like to think back on the immense hurt that was caused by the brutality in Paris, she acknowledges the ways in which Radical Call for Love responded to that trauma. “It was just a really hard moment for everyone, and as a fashion designer, you know, I was like ‘OK, I’m going to change, and make myself slightly more useful than making skirts, because otherwise I’m going to get depressed.’ I had a really important moment in my life, in which I understood that fashion did not have to be futile. You can speak with fashion, you can speak with garments. You just have to be smart enough to understand that.” The title, an appeal for compassion and openness that articulated the sentiments behind the designs, was borrowed from the writings of Marine’s boyfriend at the time, a student in political science, and chosen just a few weeks before the collection’s first show.

Based on the perceived references to Islam in Radical Call for Love, much of Marine’s audience drew links between the collection and the culturally freighted current events of the time. Marine does not fault anyone for reading into the designs, but cautions against obvious inferences leading to facile takes on the concepts, societies, and traditions they may represent. “People just go directly, they see something and they don’t reflect. It’s the same with the moon. When I use these references, of course aesthetically I think they are beautiful, but everything is political today. I’m just trying to be radically open about what things mean, and where they come from.”

Whatever the interpretation, there was no doubt that Radical Call for Love was an overwhelming success. The collection caught the attention of retailers including Dover Street Market and Opening Ceremony, and played a huge part in Marine winning the 2017 LVMH prize, which brought with it a whole new degree of visibility and respect—not to mention a significant new budget. The accolade also came with expectations and heightened responsibility. Serre’s first order of business was to assemble a small but dedicated team, and upgrade her workspace. Then it was back to the garments, and the accelerated production cycle that she now found herself beholden to. But Marine has always been self- assured, and was not about to make concessions in the name of any obligation to industry or trend.

And thus, true to the spirit that activated her inaugural collection, Marine let her feelings and conscience dictate her designs. The resulting collections, released periodically along a path stretching ever further toward stardom, have been heartfelt and innovative—and, in contrast with the corporate mindset, not singularly focused on growth. “I just want to make sure that what I do feels right. I also don’t want to grow too much, I’m basically trying to search for the balance of a team like we are now, to grow in health.” There are a few keys to this healthy growth: Marine’s desire to bring production in-house wherever possible to ensure quality and ethical standards; her eagerness to disrupt wasteful and ecocidal supply chains, by repurposing vintage fabrics for one-of-a-kind pieces in her line, for example; and her willingness to step back, take a break, and reassess if things just don’t feel right.

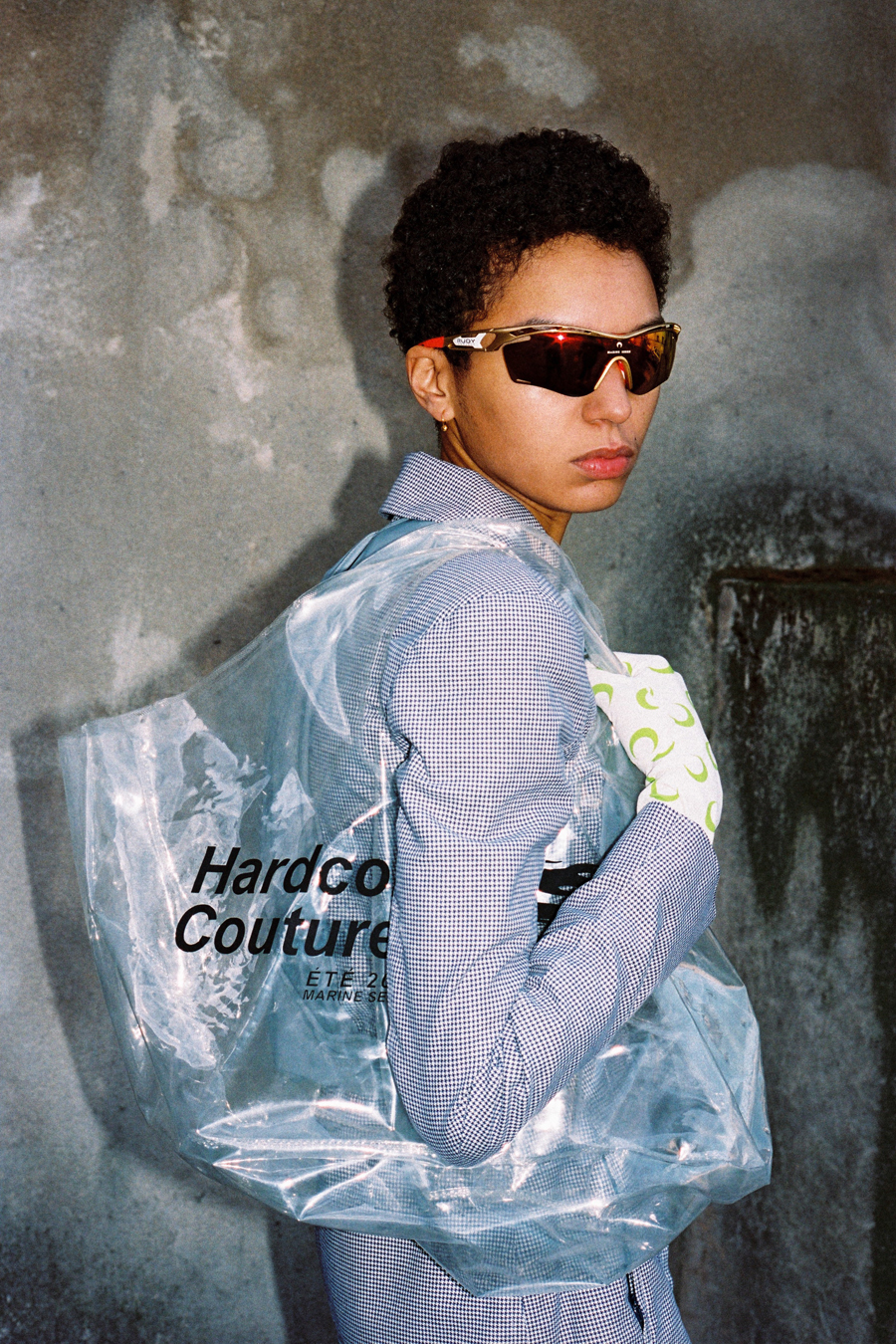

Feeling right has necessitated some creative flourishes along the way, like designated certain of her pieces as “FutureWear,” defining the term as a more considered concept than simple sci-fi-inspired style. “When people are saying that I’m doing futuristic garments, I don’t think so. You can easily work with a future aesthetic without talking about the future, you know what I mean? You can use shiny tape, and make it look like a movie from the future, but I really don’t see the future like that. I tried to find the solution of what is the fashion of tomorrow, so it’s clearly not only in the aesthetic of the future. Future, for me, is something with a broad sense of what is our life tomorrow.” In Marine’s mind, one aspect of that future life is the chaos and resulting demand for ingenuity that will arise as we deplete the resources we rely on, a phenomenon she has tried to preempt by “upcycling” used materials into her collections since 2018. “I think soon the apocalypse will happen, and then you can call me, and I’ll make great garments out of your garbage.” In another inventive turn, Serre decided to split her most recent collection into four categories, the “avant-garde ready-to- wear” Gold Line, the upcycled, ecofuturist Green Line, the collab-heavy core White Line, and the couture Red Line. Among the models chosen to showcase the looks, she cast real-life families, lending the show a sense of kinship and sincerity.

The Marine Serre brand is defined as much by its principles as by its founder. As the company grows in popularity with astonishing speed, Marine seeks to surround herself with colleagues who work with her, not for her, and who genuinely believe in the inclusive, progressive, and conscientious ideals that pervade her work. Success, to her, might be the collection standing up on its own, supported not by her leadership or celebrity, but by a community of like-minded people engaged in the design, production and appreciation of the pieces. A group bound by the shared ethos manifest in the garments, with all their familiar hallmarks—athletic fabrics and fits melded into elegant silhouettes, polycultural iterations of the signature head-coverings, and of course, the ever- present moon, a symbol that Serre hopes might one day supplant her altogether as the face of the brand. “Some retailers told me that in China and Japan, they don’t really know how to pronounce Marine Serre, so when they go there they ask ‘Where is the moon brand?’ I really like that, I think it’s great, and I wish that I can arrive there, maybe in two or three years. Where they don’t know me anymore.”