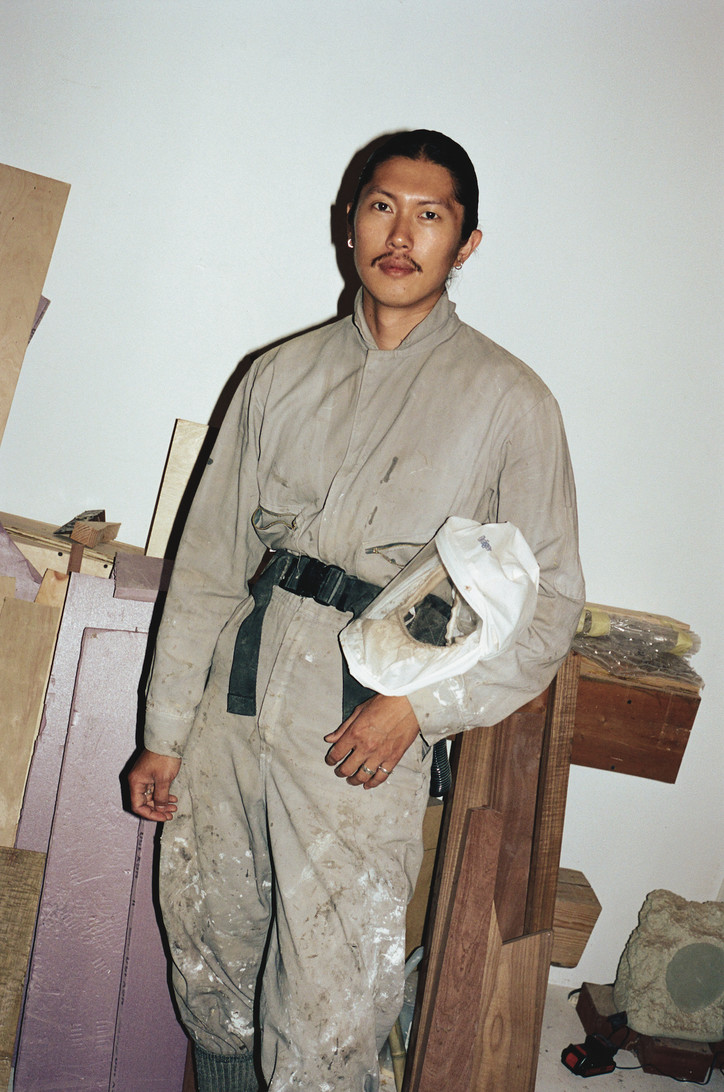

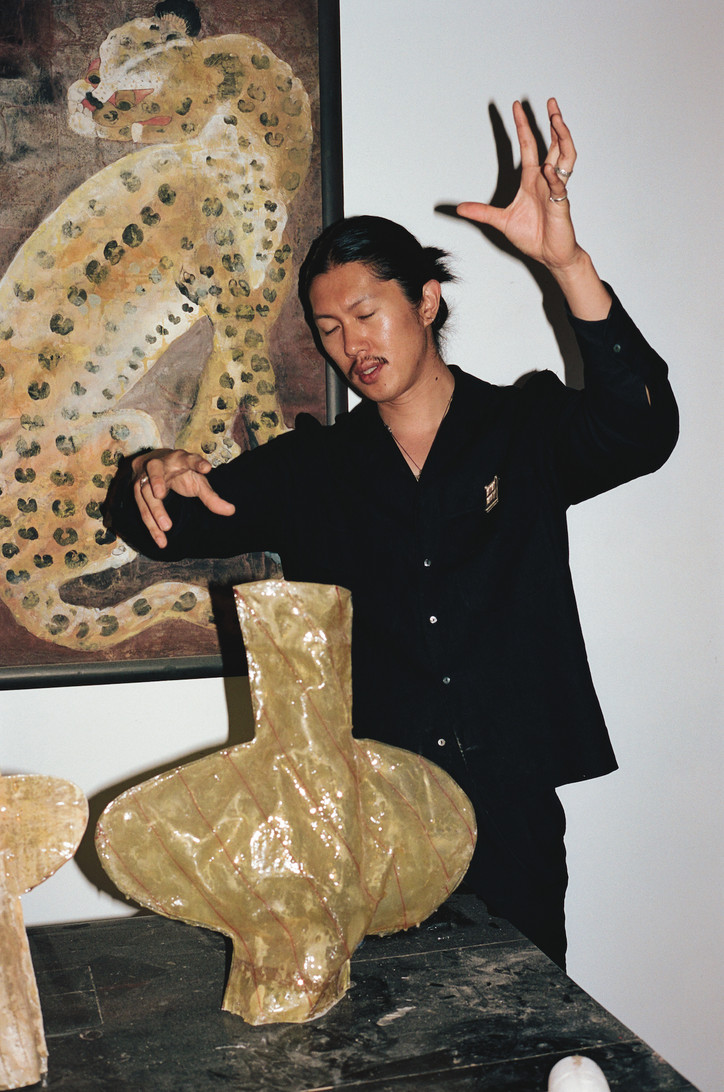

Run Through My Fingers: Minjae Kim

EO – Your childhood was spent in Korea, but you spent much of your adult life in the US. For myself, being a child of immigrants, I feel that I’m constantly navigating a sort of dual identity. I very much feel American, or even Western, but there’s a part of me that can tell that I’m connected to cultures, histories, and ancestors that exist outside of that limited worldview. I believe you referred to the same type of understanding as, “being in two places at once.” Can you speak to this duality of your identity, and how it plays into your work?

MK – You could say creating this world around me through work is always an attempt to ground myself, and that comes from that sense of duality — or that sense of being an alien everywhere. When I came to the US, I realized that I'm a foreigner here. At that moment, I didn't realize that that relationship is also reversed when you go back home. So, you're kind of stuck. You don't really get that strong sense of identity through your citizenship or what country you belong to anymore. However, I’m finding community through making my work. The past decade, I've been studying painting, architecture, and design, and that gives me my strongest sense of belonging. Especially since I'm able to be in the US through that. I have an artist’s visa, so there's this funny sense of work almost coming first, because now it is not my passport or citizenship that is allowing me to be here. Technically it is, but it comes through what I create. Everyone that I meet, whether it’s in Korea or in the US, is inevitably part of my world. So being more specific with my work, and getting in touch with people who understand that and appreciate it, becomes my place of comfort. It makes me feel grounded.

EO– One thing that is becoming more apparent, is that what is described as “Western Art” really is borrowed from many other cultures. I saw a description of your work as inverting the modern appropriation of non-western aesthetics. Do you think that is an accurate description, and if so, is this something you are acutely aware of as you are creating your artwork, or that just happens spontaneously?

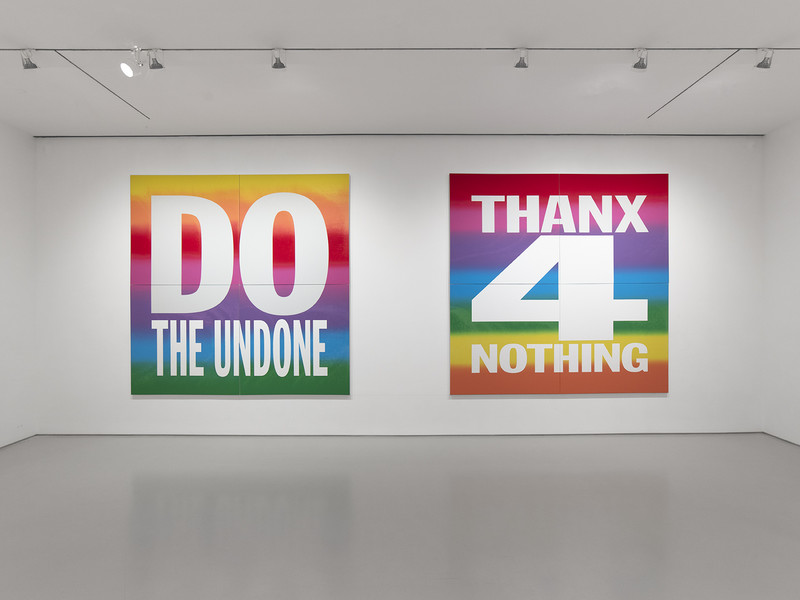

MK– I'd say it happens more spontaneously. I don't try to think of the underlying meanings too much when creating work. The work has to fit. It's all about the context, but then again, when I'm creating work with the most liberty, it’s not that I'm trying to always subvert the relationship between Western culture, but it's almost inevitable because of my background and the way I was brought up. Modern Korean culture is very specific to the Western world, so I've always been surrounded by it, and then also, the experience of coming to the West, being educated, and then creating work in that context. I can't help but be conscious of this dynamic. I take references from everywhere, but if I'm making a reference to Korean tradition, then it's read a specific way here in the US. In these scenarios, it almost seems as if I'm representing my heritage or something, when that's not necessarily a conscious move. So, in that sense, knowing the consequences of my decisions, it is something that I'm always aware of. Then there's another aspect of me not coming from the West. There are people that I've met in the industry who very much grew up in a world governed by Western design, and that whole saga and history was part of their heritage. As a result, they’re kind of breathing it, and that's a very different context than what I have. There's a part of my practice where I feel like I'm just appropriating everything just by creating, and that a big part around my first show at Marta was because I felt like I had to address that, because I was working with some type of Western typology.

EO – So, my understanding of what being a creative is in this current time is that I feel like all these lines are blurring between industries. Now the art industry is the fashion industry, is the furniture industry. It’s all the same. It’s all creative, and it’s all interconnecting, and artists are no longer limiting themselves to what they were first known for. They are moving on and evolving. I think the future of creation is not bound by any labels. Whatever you are focusing on at the moment is done at a high level that has artistry and creativity. Would you ever do traditional architecture, or interior design work, and have that be an extension of your artistic practice?

MK – I think the simple answer is yes. I always found working in architecture or interior design, that being an architect was portrayed as a parallel to being an artist, in that you are creating a vision and having control of the project. There’s this idea that a good architect can do everything. A lot of times, when you are in the industry, you realize that you are bound by so many things, and there's actually such little creative outlets because of the scale of the projects. I think that's also why I found myself so passionate about the side projects, because in these smaller scale projects, I was able to have the vision and control, or like, you would typically carry the whole thing through without an interruption.

I'm hoping that one day, I will get a project that will scale up into architectural scale, and when it does, it'll be very different from work with architecture or interior design as part of a studio. I'm excited, and I'm very curious to see how that manifests. But, like you were saying, it doesn't just limit [me] to that either. It’s about creating a brand for yourself, and there is no limit at this point to what we can do if it feels in line with what you’ve done before. Also, maybe it's a matter of how you make that transition.

EO – Yes, I agree. I think in this day and age, as a creative, it’s important to stay fluid. So, Is functionality a guiding tenet of your fine art proactive, or are you primarily focused on the aesthetic nature of what you are creating?

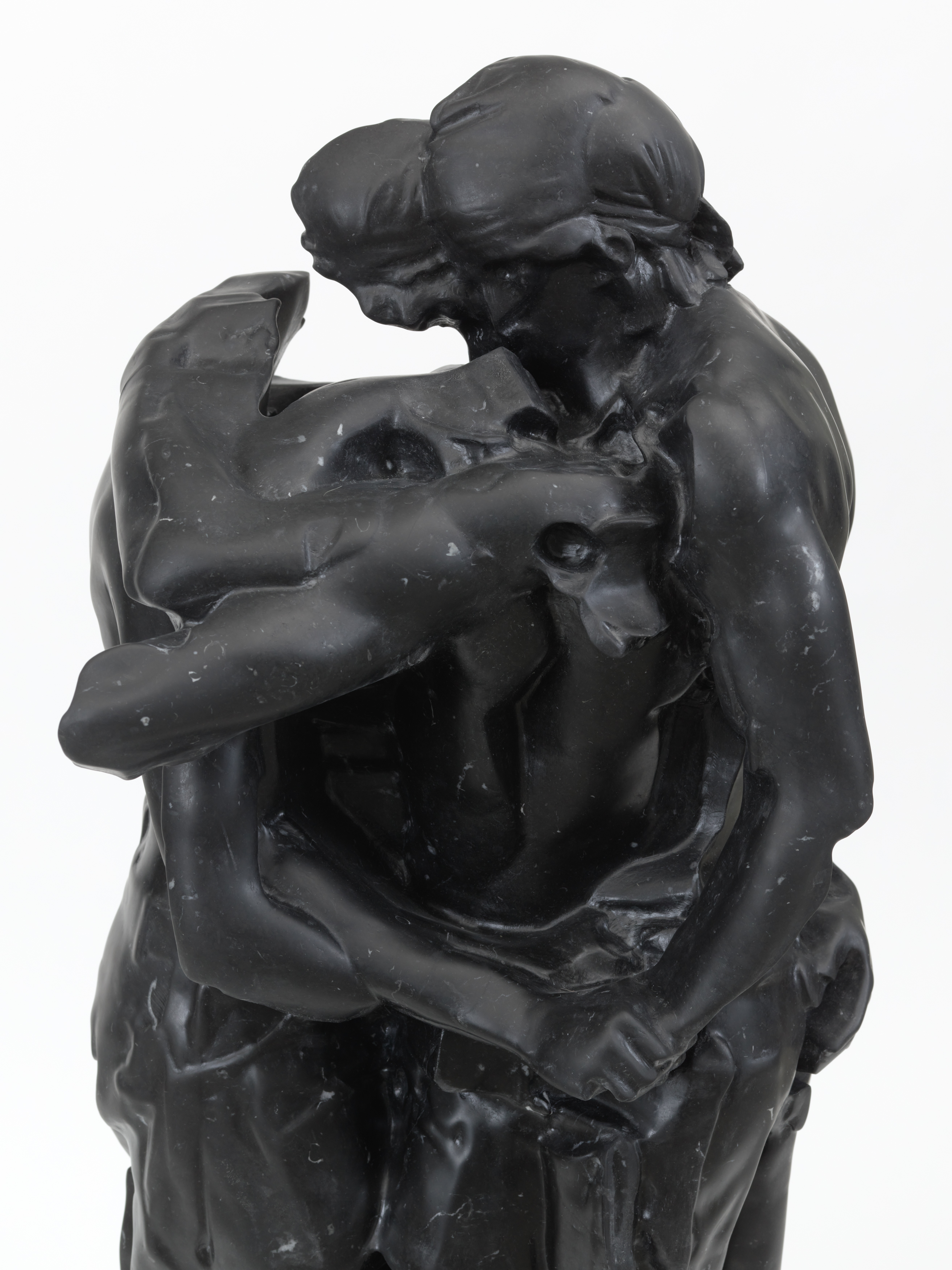

MK – I always try to do both. I’m pretty firm about that. It does have to function. It's also only to a certain degree. In the design world, there’s a sense of, “this is the best way to solve this problem,” but that's not what I'm trying to do. This is a way to build this, or assemble it, and it might not be the best way, but it's what I choose to do. It does have to function. That is a big part. Especially with the fiberglass, people who are not familiar with the material or process don't really expect it to hold any weight. Especially because now with so many people's work, you just see the work through images. Part of the challenge for me is to make satisfying aesthetics, but I don't think it’s an elevated or interesting work if it doesn't function as its typology. If it's a chair, a person should be able to sit on it and be relatively comfortable.

EO – I’ve seen that you collaborate with your mother who is also an artist. Can you tell me about what it’s like working on art with your mother? How does she influence your art works? Has becoming a fine artist strengthened your relationship with your mother?

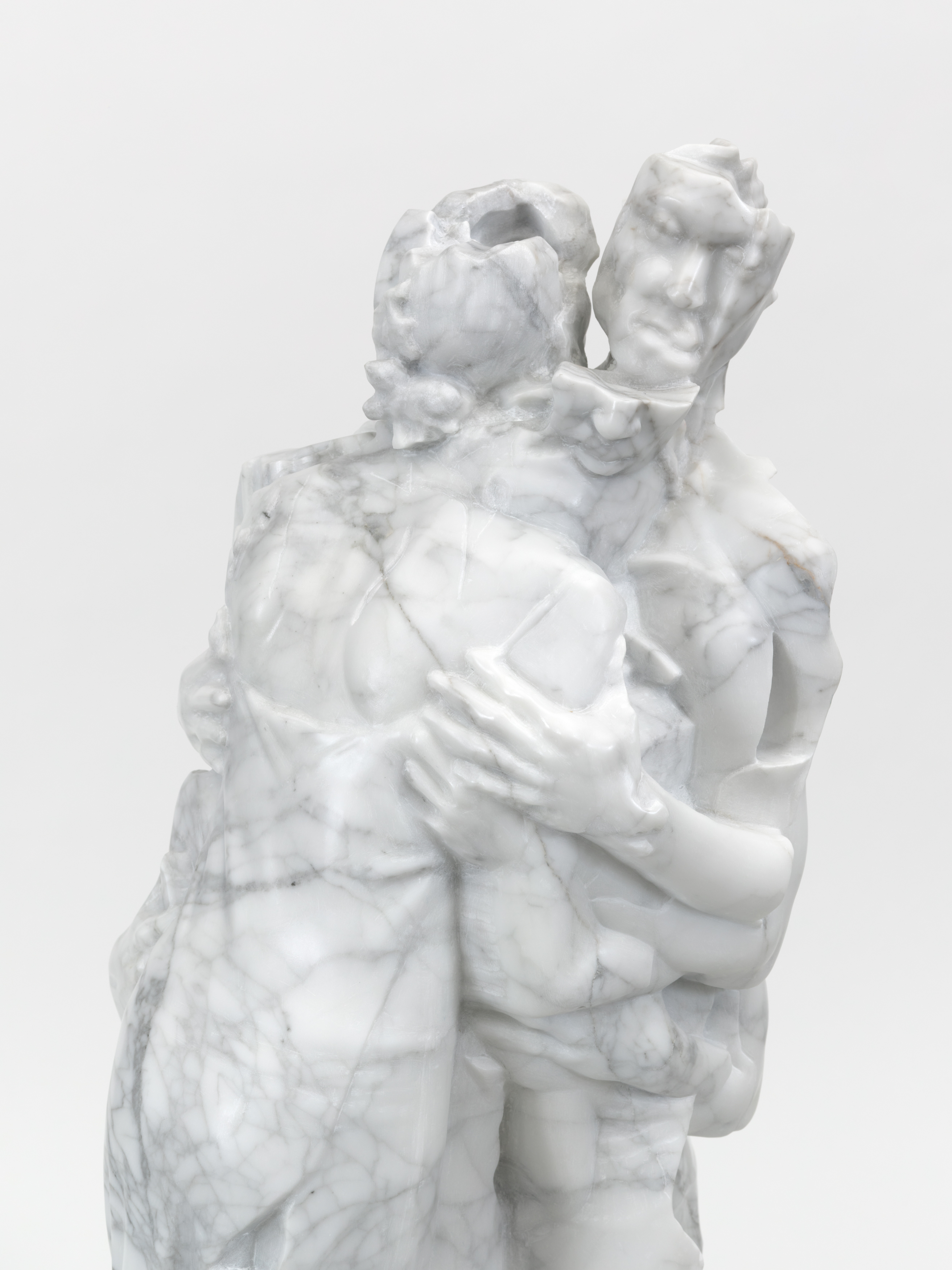

MK – Basically, the way she influences my work is no longer a conscious thing. That’s something that we were establishing when we did the show together, was how well our practices worked together. which to me, means there's a genealogy of aesthetics or work method that I picked up from her that's so deeply ingrained in me, that I almost can't avoid making work that doesn’t relate to hers. When you simply put it together in a room, you can see that. I think you can argue that, in the show we did together, all the work was done by a simple hand or single vision. So that's the baseline, and then she always gives me feedback, but there it turns into the whole parent-child thing, and then me seeking approval and never really getting it. That was kind of our day-to-day experience. There was this constant challenge of, “can you just like this,” or, “can you just get over yourself?” So there’s this huge kind of gap between these two realities. One part is super petty, and the other is so deep. Part of working on this particular show together was bridging that gap by formalizing all these steps or logistics into it. Now she's back in Korea after the show, but if I send her something I made, I still get annoyed when the first thing she says is not like, “wow this is amazing.”

There's another aspect, where the takeaway of working together now as artists gives my mom comfort in a sense. It’s not something that she has said explicitly, however. I always felt like she had to make compromises in her creative career in order to raise me, when she should have been developing her career. She could have been showing at more galleries, or schmoozing with people who could have furthered her career. Instead, she was teaching classes, or teaching kids, because that was a way to make quick money rather than, like, building a career. So, she always had this kind of duality in her practice. It was never like a single effort of just being an artist, and maybe now there is a sense of comfort for her as she's able to see me do that. With us doing the show together, I was able to bring her into my world, and I think it was important for her to see. She's almost 70 now, and there was all this talk about, “maybe I'm too old to really focus on my career as an artist,” and I'm trying to erase that from her mind. She can paint. She can pick up a brush. There are not many other careers where you can literally just keep working and find that fulfilling in your older age. So, I think we are getting one step closer to that

EO – That’s amazing. I’ve always had a dream of curating a show with my mom, for similar reasons. She isn’t a curator or artist, but is an extremely creative person that could not really see her creative potential because she was providing and creating opportunities for me to do so. I think it’s amazing that you were able to do that with your mother.I always end with a sort of a general question. What are some of the lingering aspirations that you aim for with your work?

MK – There is always this sense of creating an environment. I guess that that is a big aspiration for any artist. However, the experience of working on something like Rothko Chapel, where, as the artist, your vision of the world becomes a whole – at least within those walls. It’s the creation of environment or worlds through my art that I aspire to continue doing and building upon in my practice.