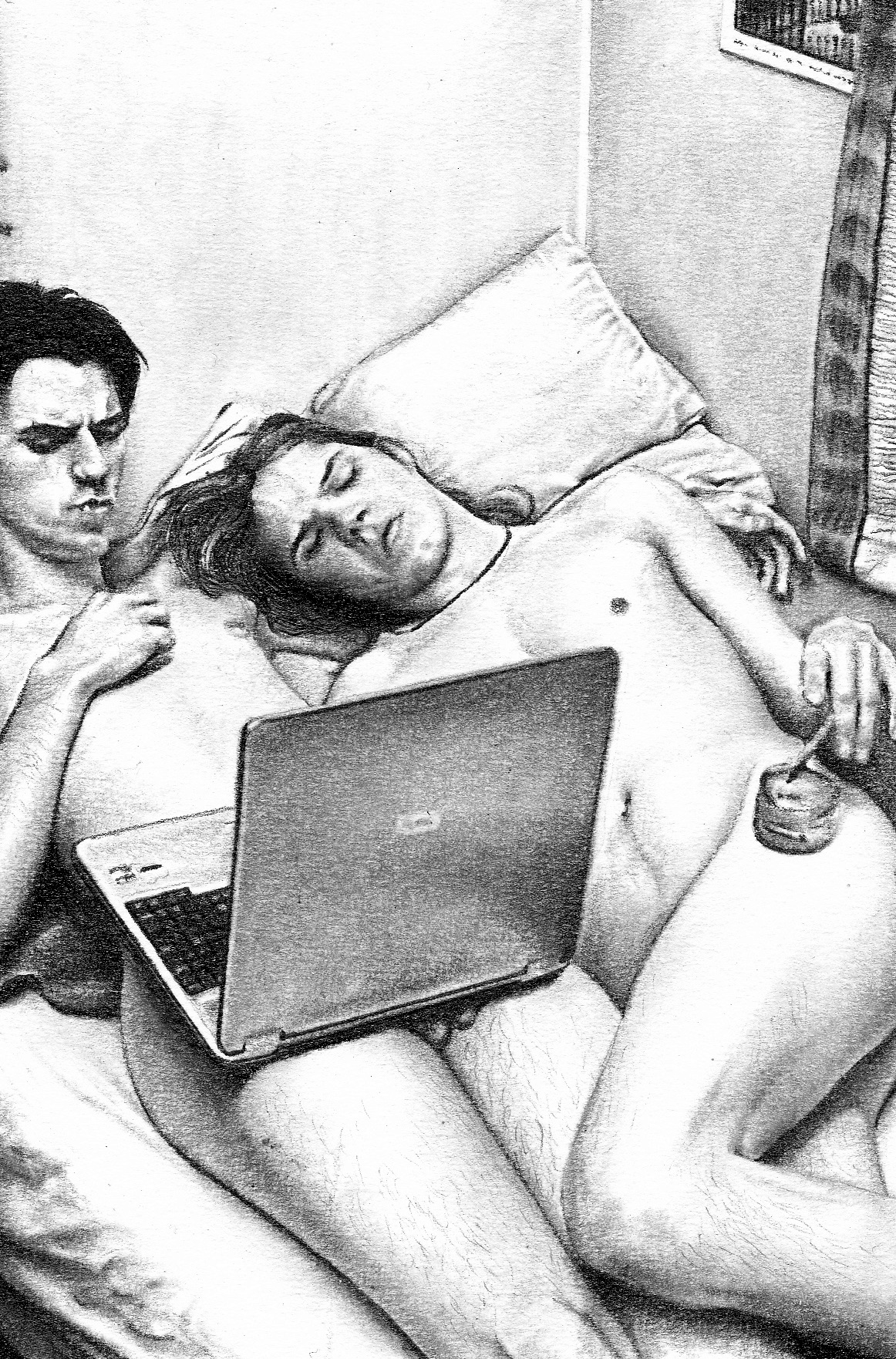

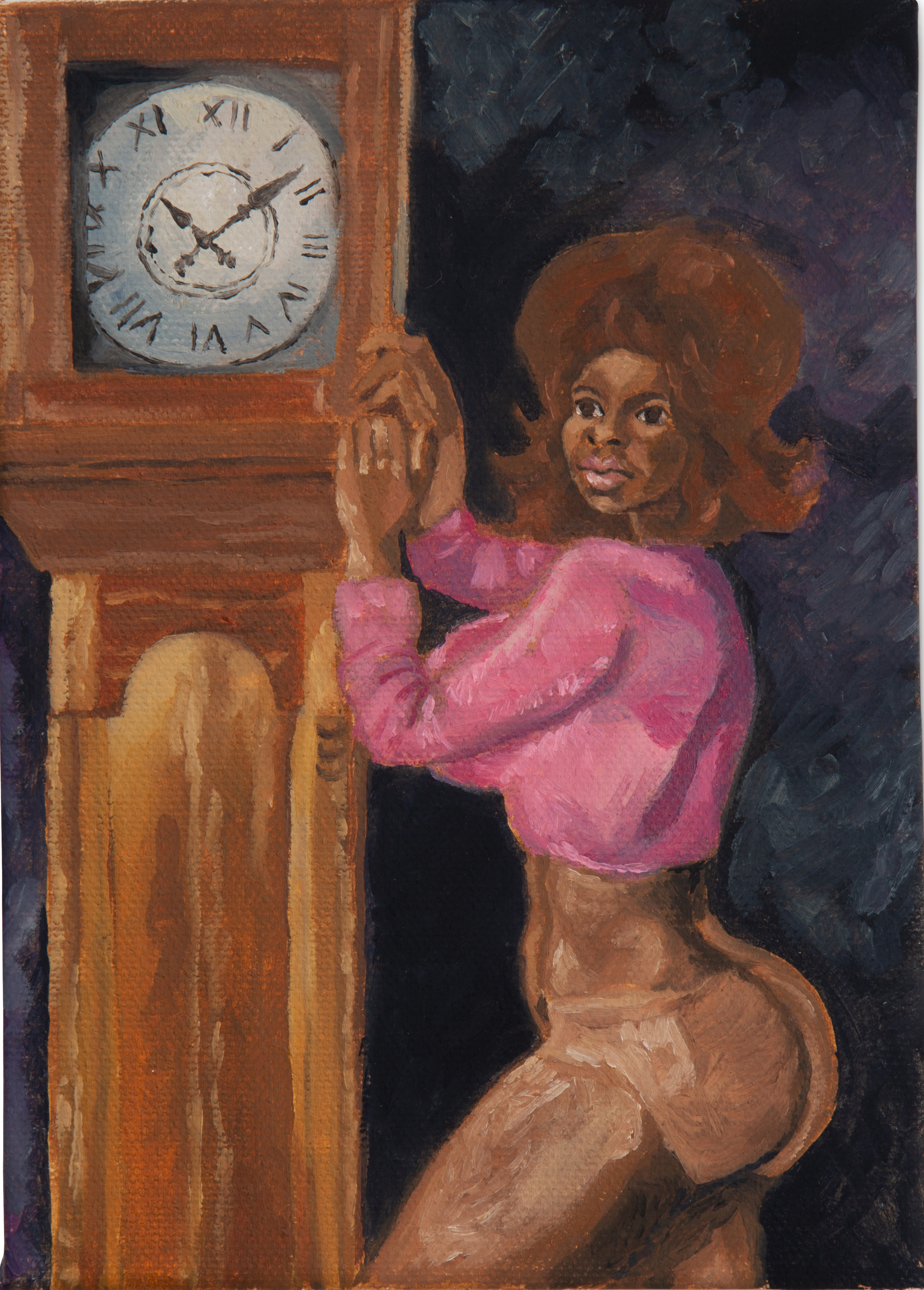

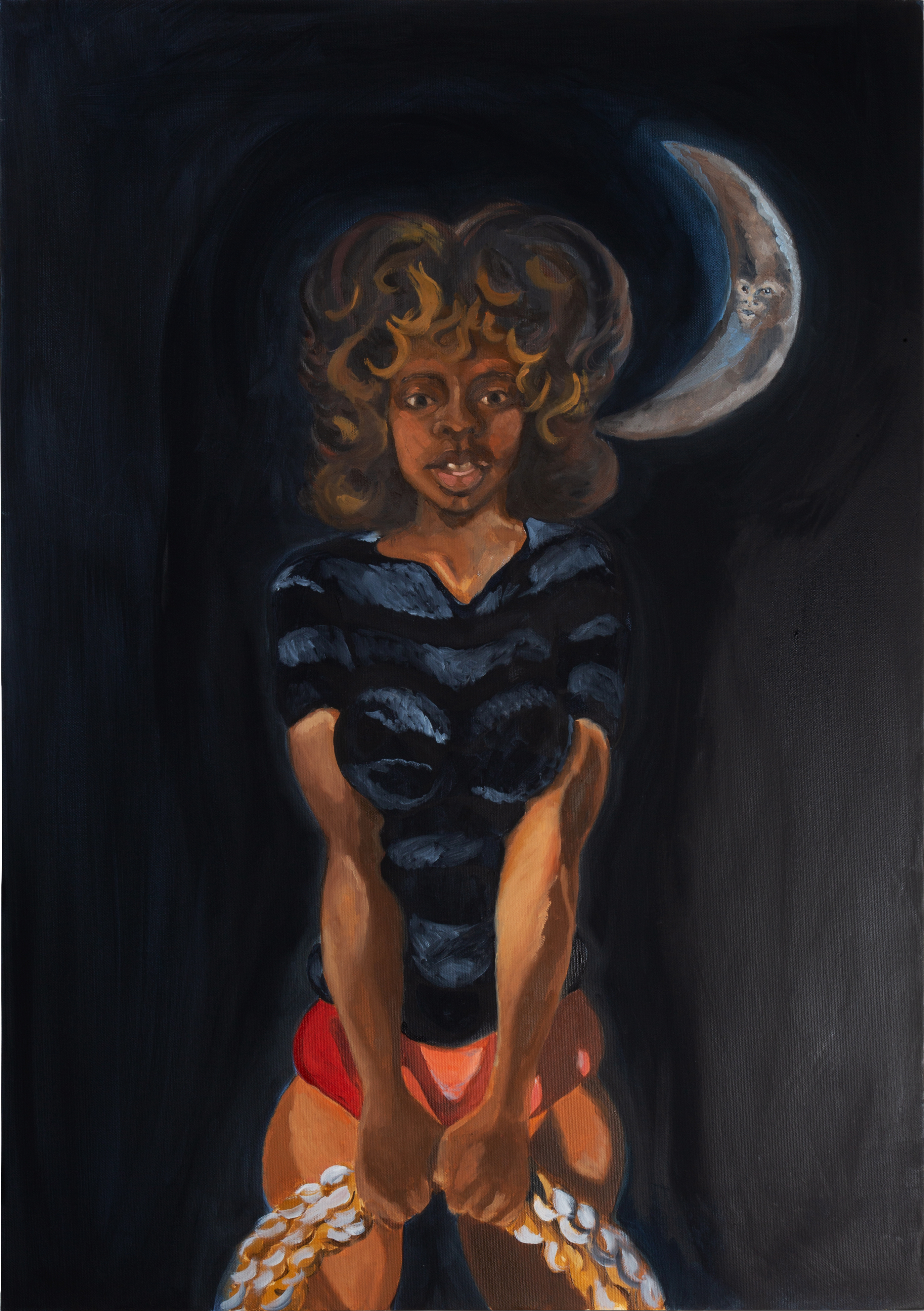

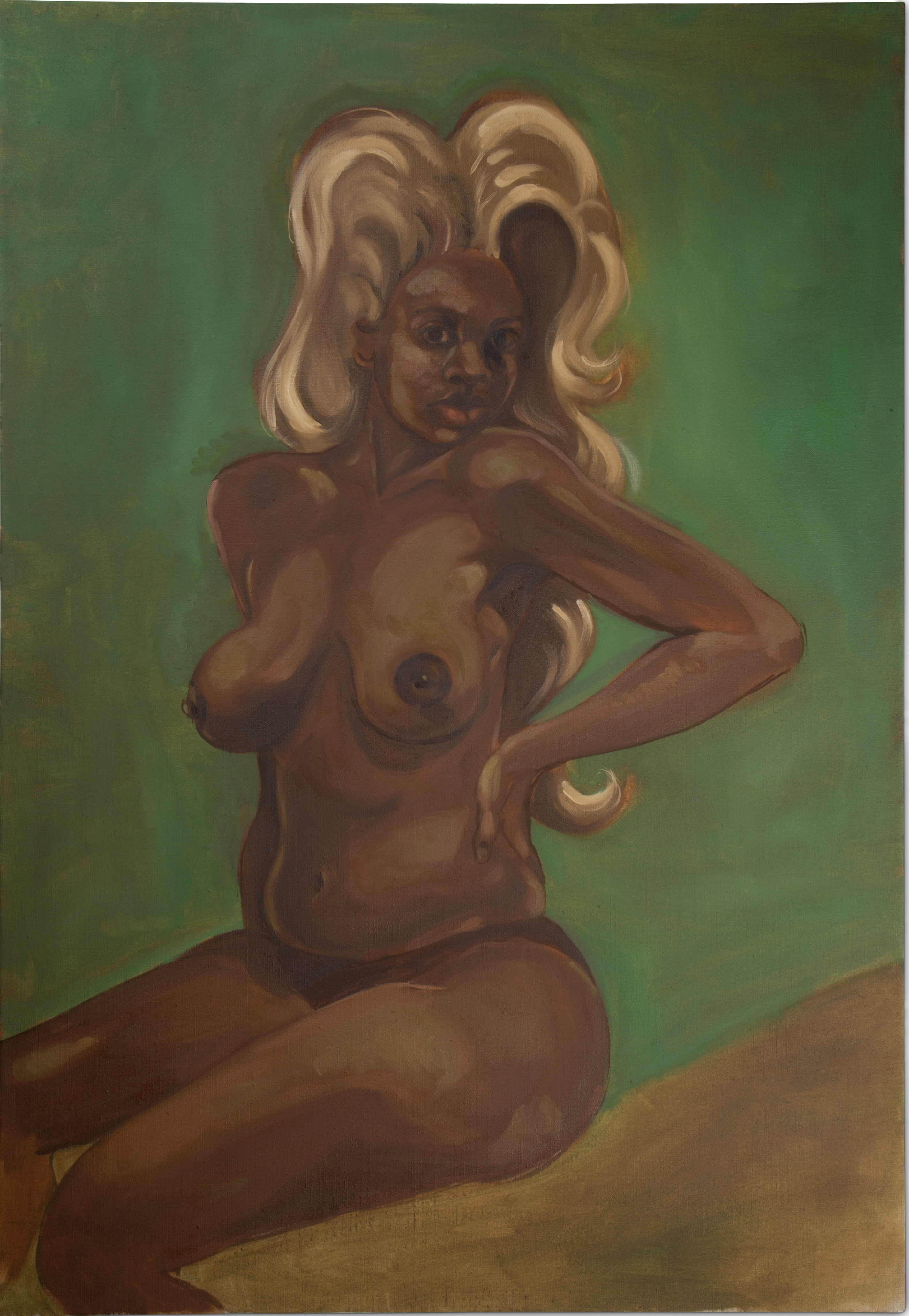

Somaya Critchlow and the Erotics of Projection

Critchlow’s portraits are like jazz: erotic, intangible, experiential, and wonderfully opaque. There is an electric verbiage to her visual language that celebrates the process, the dance, of questioning rather than the pursuit of a binaric ‘truth’.

Following her exhibit, 'Underneath the Bebop Moon', at London's Maximillian William gallery, Critchlow was interviewed by American artist Tschabalala Self to discuss the iconographic significance of the Black female body in contemporary culture.

Can you tell us a little about your backstory? Where are you from? Large family or small? Favourite childhood activity?

I was born and raised in South London, my mother’s side of the family descends from Caribbean, Irish and British heritage while my father’s family is from Nigeria. I grew up in Streatham, which is an interesting place. The rapper Dave has a song named after it. My experience of growing up was as part of a large family on my mother’s side. Her own mother, my Grandma, Gail, also comes from a very large and interesting family that arrived in England from Kingston, Jamaica in 1919. My great grandmother, Pauline Henriques, was an incredible woman; she was both the first Black Magistrate and the first Black Woman on British TV. She was one of six children, there is a book about the family, The Jippi-Jappa Hat Merchant and His Family: A Jamaican Family in Britain. I’ve been learning a lot about them recently; it’s been helpful in light of current events. The childhood activity that I probably remember most was spending time in my grandpa Keith’s studio at the end of my grandparent’s garden. I got to learn about Islamic patterns and Geometry, and it was where I first discovered oil paint. You could get lost in that room for hours, amongst piles of papers and books, in the heady, musky scent of rose incense while listening to gothic sounding classical music like The Sixteen Miserere Mei Deus, it was quite a contrast to the reality of growing up in a place like Streatham.

When did you first become interested in art? Who was the first artist you knew?

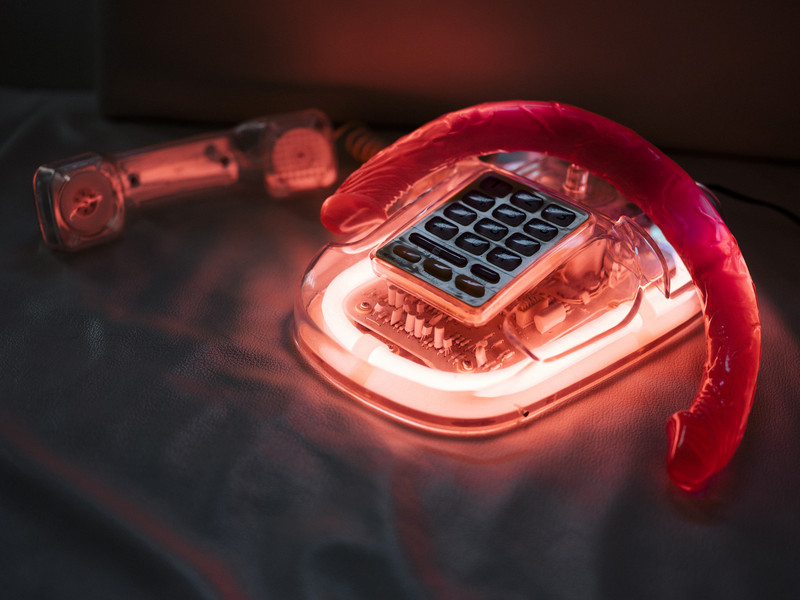

I first became interested in art seriously after being taken to see a Pipilotti Rist exhibition in Barcelona at the Foundacio Joan Miro by my mother. It was titled Friendly Game – Electronic Feelings and I must have just turned eighteen and been finishing up sixth form. I was blown away by that exhibition and how intensely I was moved by the experience. You’re entirely submerged in Rist’s universe, which seems to abstract reality, creating alternate nonsensical versions of all things that seem familiar. There was a piece of work in the show titled Sip My Ocean, a projection of people swimming around in the Ocean and Rist singing "Wicked Game" by Chris Isaak, she drifts in and out of softness to a more hysterical sounding singing. I think seeing that exhibition had a really profound effect on my interest in art.

The first artist that I can remember knowing was probably Rembrandt and looking at all of his self-portraits, drawings, watercolours and etchings. I think I knew him in a way of trying to understand and learn about draughtsmanship and the craft of art. My grandfather scanned a ton of pages from his books and put them all in a fact file for me.

How have you been feeling during the first half of 2020? How have you been spending your time? Have world events influenced your work or perspective?

It’s been really tough, and then at the same time I have been so lucky as I have been able to open my first solo show in London. Initially I was in a very strange place trying to pull together the show that I had been working on for over a year and a half, when Coronavirus hit and the whole world started going through this huge shift that we’re still experiencing now. I also think that change and the sudden excess of slowed down time that having to stop and stay at home has given us, has really explicitly highlighted the inequalities of contemporary society in a way that many people could no longer ignore. There has been a lot of questioning the systems in place and how we live. I have been spending a lot of time in my home listening to podcasts and catching up on reading as well as drawing, more than painting, which I think at the beginning was easier for me to navigate what I was experiencing through its immediacy. A way to grasp back at reality, which felt a bit like it was slipping through my fingers— I’ve always been a bit of an anxious person and I find drawing very grounding. I think less when I draw and just sort of let my subconscious take over. I think a lot of world events have, for me, kind of reinvigorated the basis of my work; that there is a need to view things in a new way and question what you think you ‘know.'

How have you found America during your travels to the states?

I have found America both interesting and strange. It is very culturally different to the UK and then at the same time there are similarities. I do always feel quite disturbed by the stark inequality and lack of fundamental things like health care, and you can really see the effects that this has on people. I remember seeing quite a few people who had lost a limb out in the streets or in the subway, more people than that should happen to when there is modern medicine ready and available. It makes me conscious of the UK and how desperately important it is to hold on to the National Health Service and to not take it for granted. Then, when I look at and get to engage with the art scene, I am amazed by the community of people that come together and support art. I haven’t really seen enough of America to create any sort of overall view, as it’s so big and I imagine things really range from place to place, but I do find New York amazing. The number of galleries, projects, independent bars, restaurants and concepts that people put together is exciting in a way that I haven’t really seen before, which is very special. I really hope that New York is able to preserve that despite all that’s going on right now. I think the communities are super strong and resilient. I also think it’s a complex political landscape and you experience that in the culture.

Do you believe your work is viewed differently in the USA vs the UK?

Yes, I think so, but I’m convinced that a lot of the difference comes down to social political context, in that, as places, the UK and the USA are quite different cultural environments. I think the UK is more traditional and slower to move forward when it comes to supporting emerging artists, and work like mine is easily overlooked in the same way that we overlook who and what it represents. While in the USA I think there is a greater demand, want and awareness for this variety and in some ways, I think there always has been. Perhaps it’s because the UK is tied to this vast European history of art that it can’t seem to get away from. I also haven’t exhibited in the UK enough to have formed a full personal opinion on how my work might be viewed differently in the US from the UK. Most people think I’m a New Yorker because I’ve predominantly exhibited in America which is something that has happened quite organically. However, I do think since the opening of my solo show in London people are willing and interested to view the work with open eyes in a much broader context than I might have expected. Despite what is considered quintessentially British I personally feel very British and that my work is representative of that while it speaks to the fact that I’ve grow up in a westernised world and there is an influence from American and contemporary culture which is relevant in both the USA and the UK.

What do you find unique about your position as a Black British artist?

I think in a very simplified way my position is unique because there are not many Black British artists with a contemporary platform. I think there are about 12 or 13 black women represented by galleries here in the UK, which is crazy. I think it is also a shame that we have to think about that when we focus on Black British Art but it’s important to note that there never really has been many established Black British artists and that is still the case. Though I think things are changing. I think my position, personally, is unique because of the environment that I grew up in as a black girl in an almost all white-passing family that ironically is descendant from Afro-Caribbean. I love British culture and I think there is so much to it, and that has all come from the mixture of history and tradition and the influx of people migrating in and out of the UK and the new culture developing out of that. I feel like I’m a reflection of this and while being a Black British Artist is a complex position to hold, I find that like all things that invoke further observation and not just acceptance it can be a powerful place to operate from.

Do you think such questions are ridiculous?

No, I don’t think such questions are ridiculous, in fact I am sure that they are necessary. I think they are hard and complicated questions that as an individual I can offer a view on, but I don’t always have an answer to. I’m very aware of the terms that I operate within being Black and female and wanting to be a painter and sometimes I find that overwhelming. I don’t think it is my responsibility to have answers nor is it possible. These are grey areas, which I hope can be treated with the depth of complexity and investigation that they require. In the same way, I hope my work will be viewed like that too and that it can offer insight into the matter of being a Black British artist, as well as a sense of self-awareness.