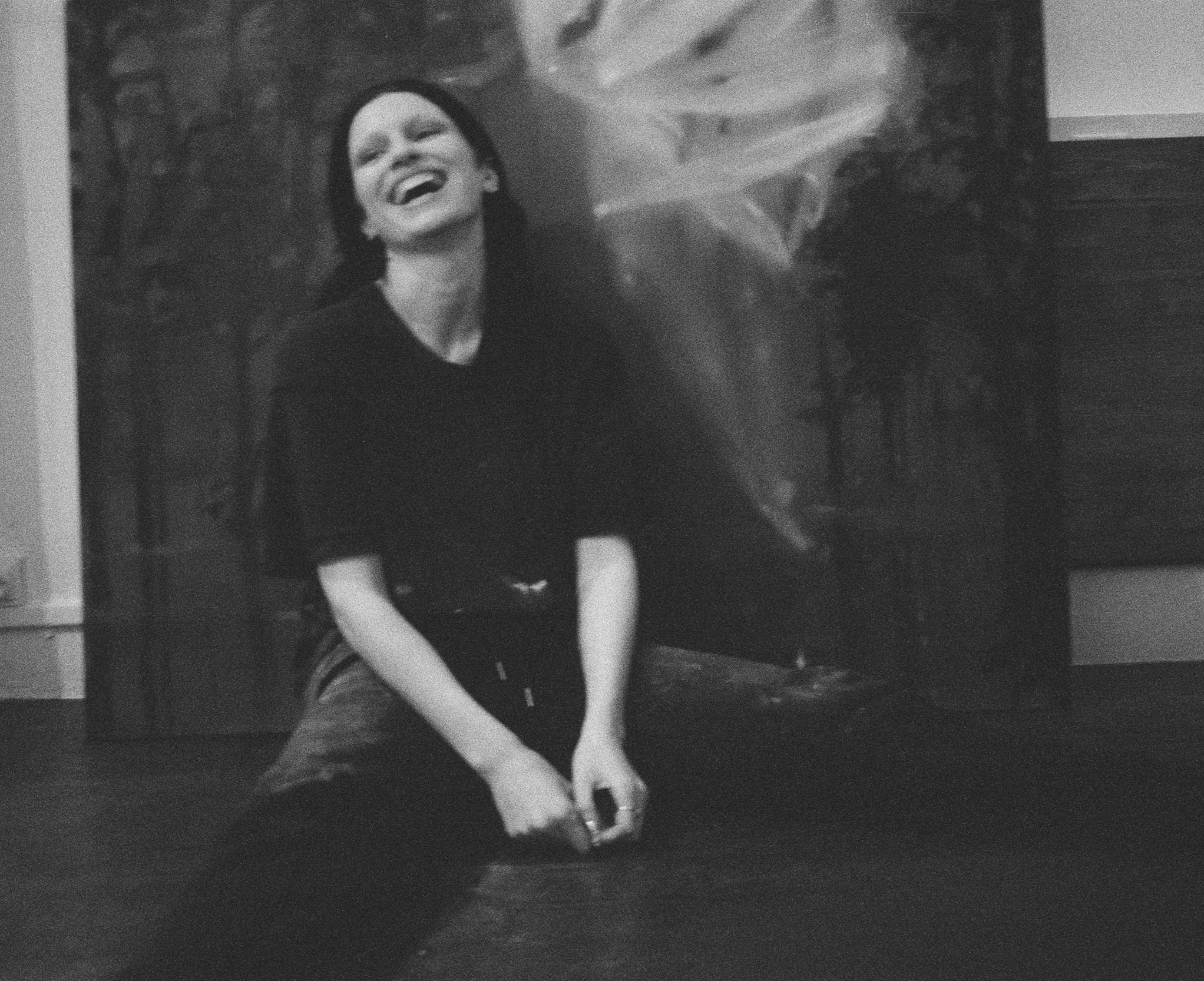

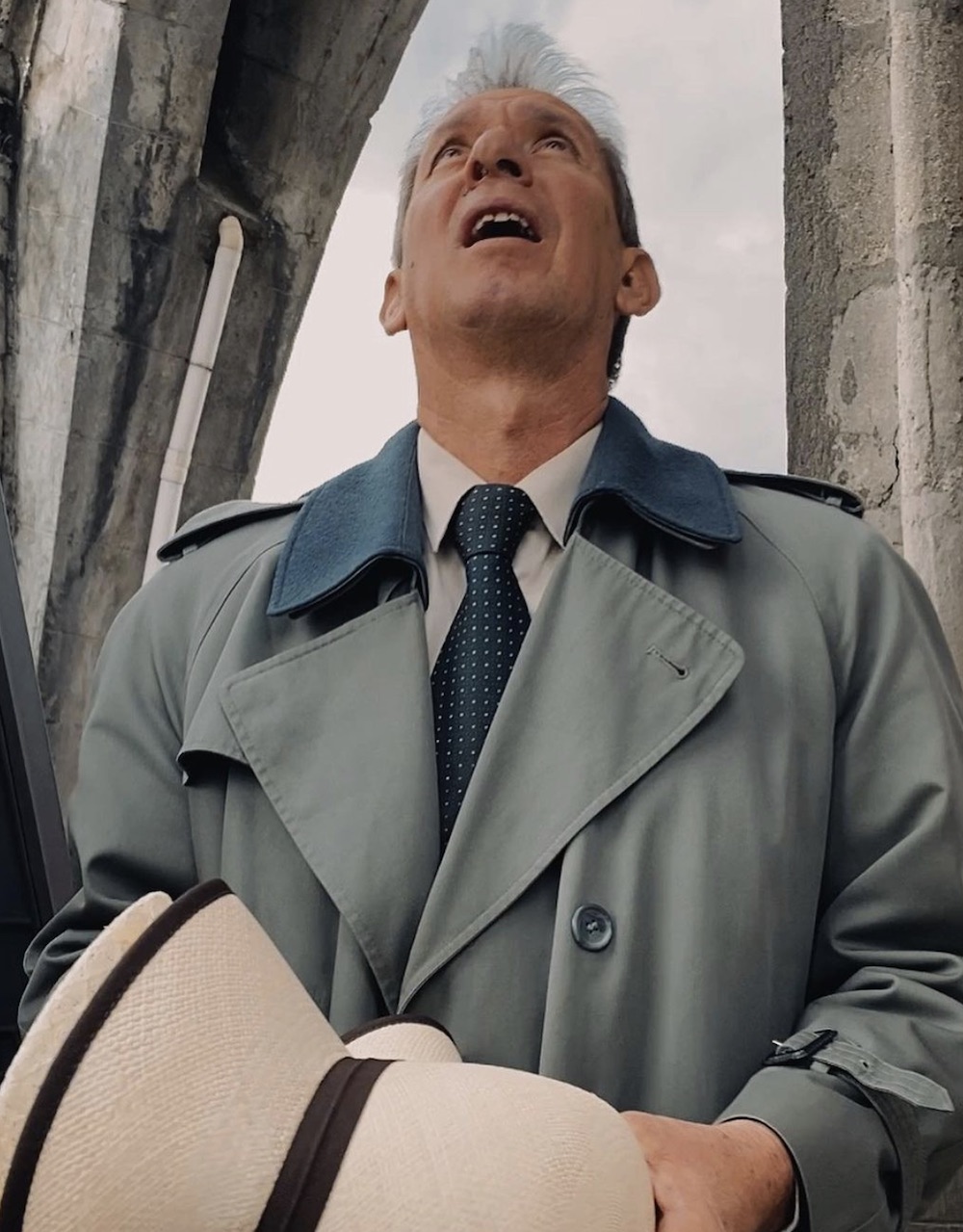

Tali Lennox Walks Between Worlds

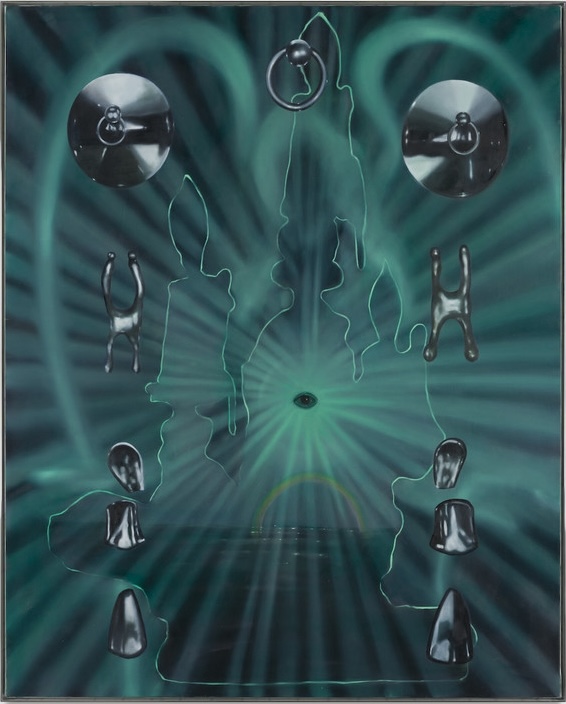

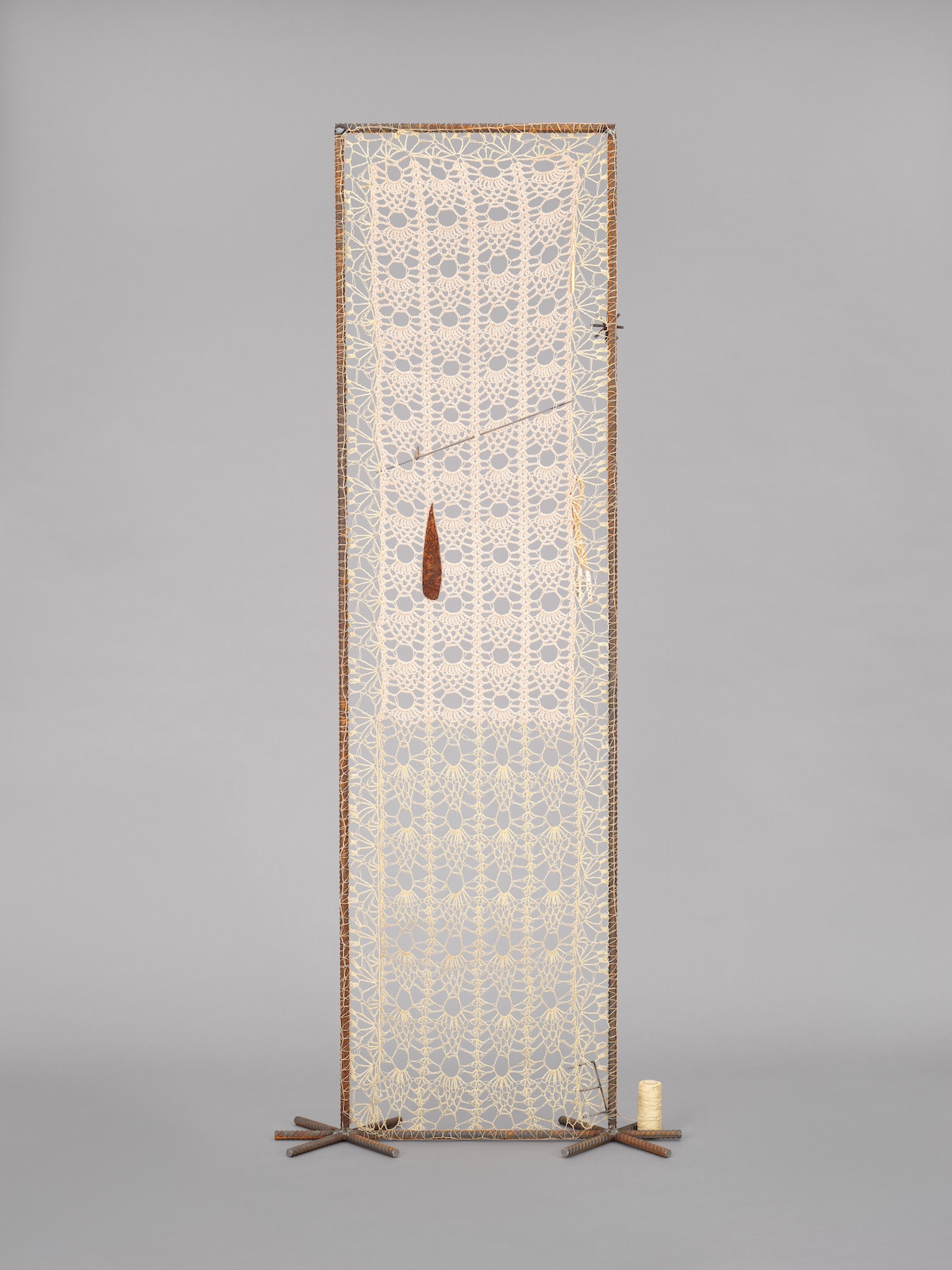

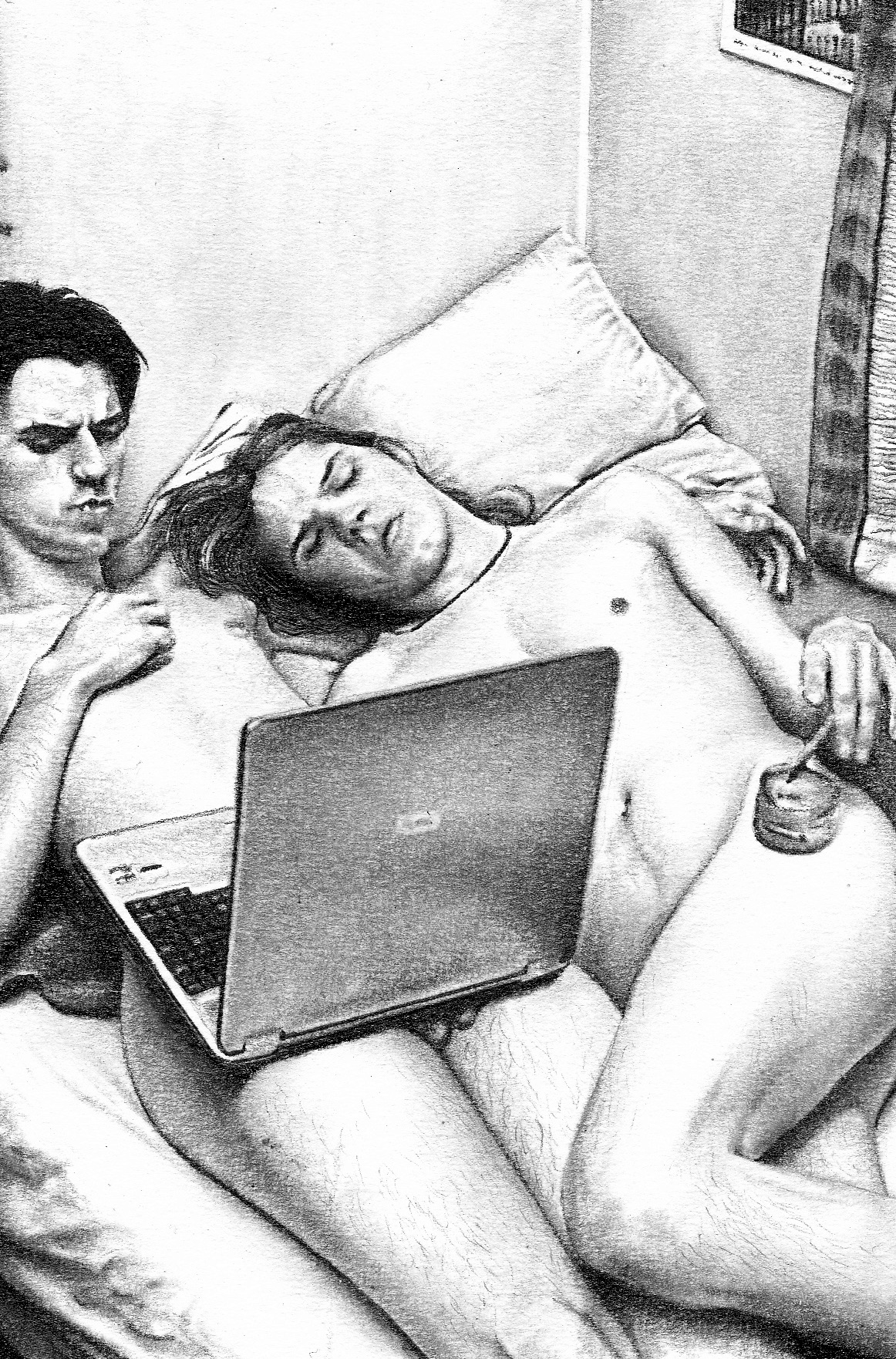

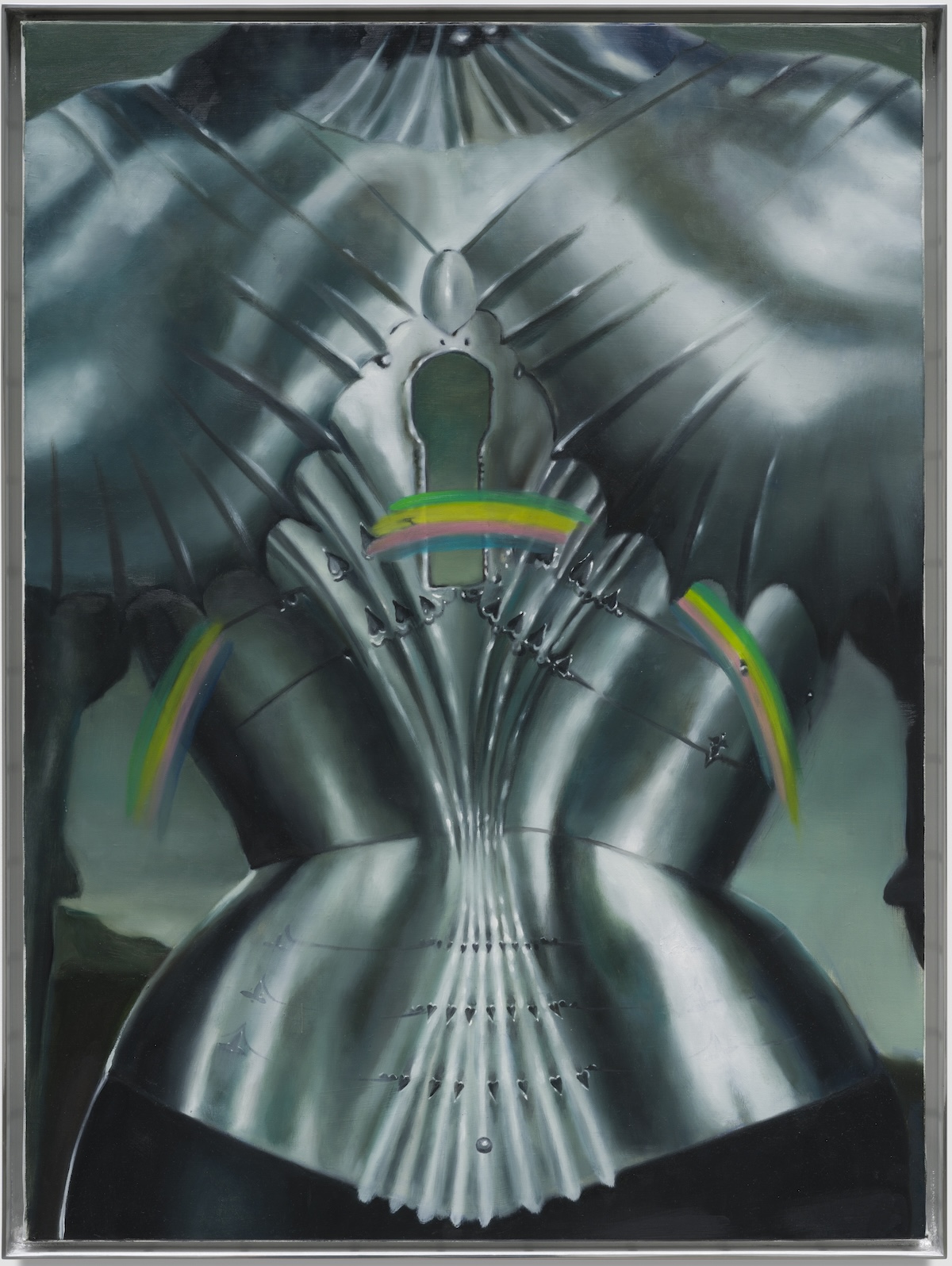

Belladonna, 2023

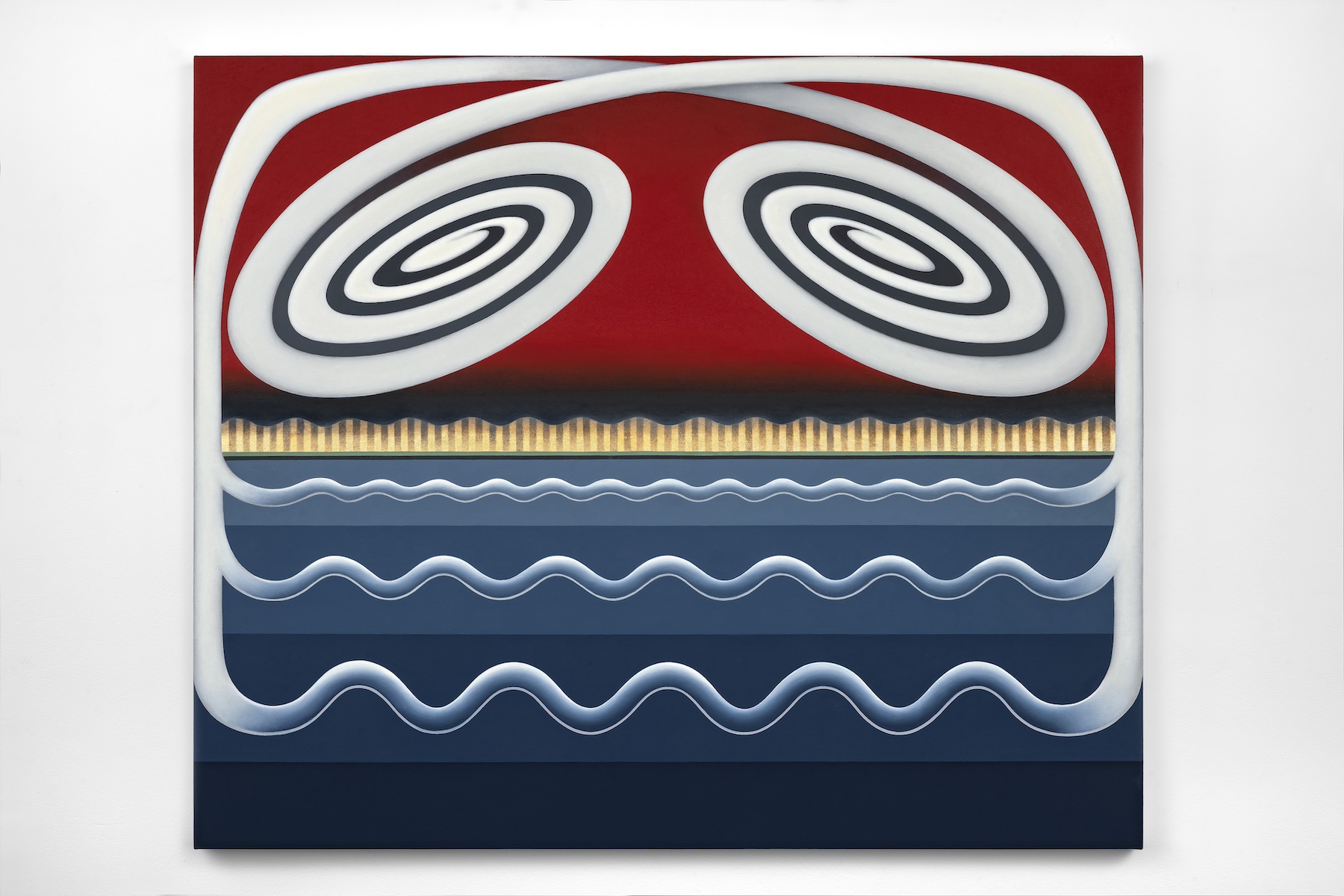

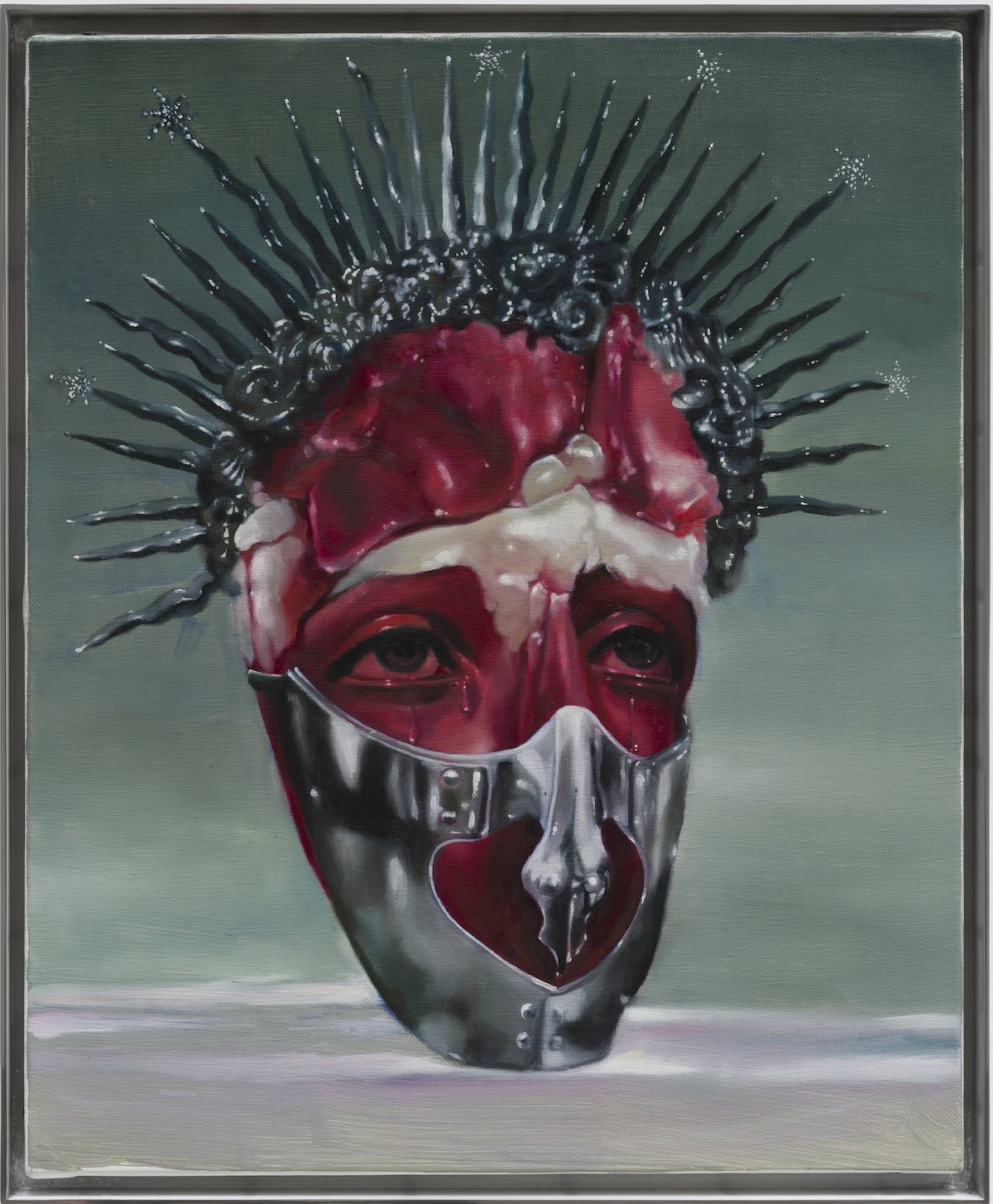

The results are just as vivid as her psychic landscape. Rendered in oil on canvas, her latest series merges mythological and folkloric references with Lennox’s own symbolic lexicon. There are shells and shrouded figures; bodies of water and gleaming oysters; crying eyes and rays of light. Women’s bodies appear in a state somewhere between pain and pleasure, tension and release, orgasm and apocalypse. Evoking the beauty and savagery of the natural world, Lennox probes our contemporary ennui and enduring fascination with the end times—finding solace in the idea of nature as the highest power, and surrendering to its cycles of creation and destruction. Currently on view at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles for her latest solo exhibition, Tremors, the paintings invite viewers to join Lennox in the space between. After all, Lennox says, “Life is but a dream."

Themes of apocalypse and end times are very front of mind these days. What do you see as the role of art in helping people process this?

I believe that painting has the power to open up pockets within us where we can access the things we’re fearful of. The show’s title, Tremors, is referencing this sort of secret fear within me, which I think everyone can relate to right now. We are in a time of general unease; there’s this sense of potential disaster or oncoming decline. I started contemplating what it means to tune into that powerlessness and the feeling of surrender. From there, I started thinking about the bigger picture: contemplating the history of the universe and the fact that the world has always had such dramatic huge cycles of change beyond what I can even comprehend.

For the past two years, my boyfriend and I have gone to sleep listening to a series called The Fall of Civilizations, which is about different empires from the past and how they fell. When you start thinking about that scope of time, you realize that above and beyond our experiences, nature has always been the puppeteer. When you also bring the element of magic or fantasy into the equation, it leads you back to the notion that life is but a dream. At the end of the day, if there have been civilizations that have lasted for centuries and centuries, and then suddenly they’re just gone, what was it to begin with?

Within the show, I’ve tried to express the tension between the minutiae of internal experiences and the expansion of the external—[finding the] fusion of that within nature. The metamorphosis of nature, the power of nature overcoming humans, this dual savagery or beauty that nature holds, and the question of, Is this a utopia or an apocalypse?

Mythology is central to the series. Where did you draw inspiration from existing folkloric legends, and which symbols and motifs arose from your own experiences in the world?

At one point, I was in Greece and I was going to quite a few caves. Some of the most profound, mesmerizing experiences I’ve ever had have been in caves and cenotes. It’s this primal feeling; it’s womb-like, it’s elemental, it’s ancient.

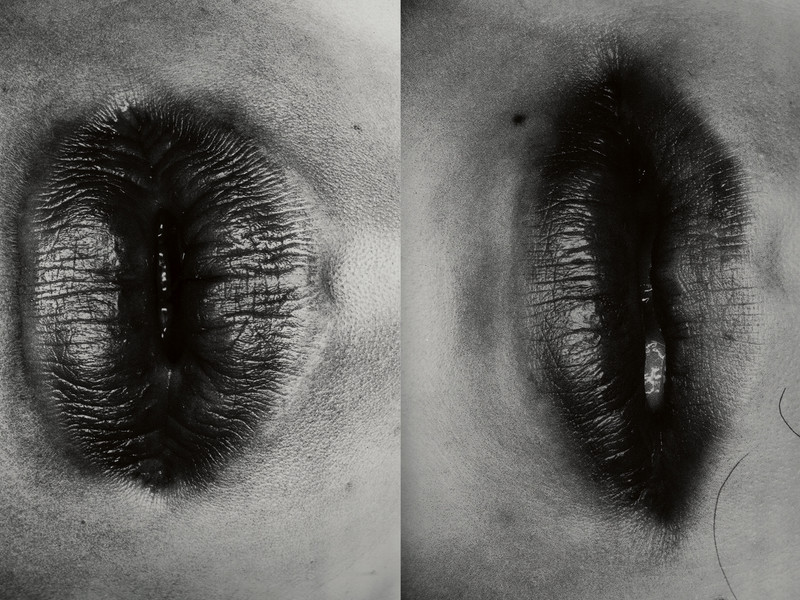

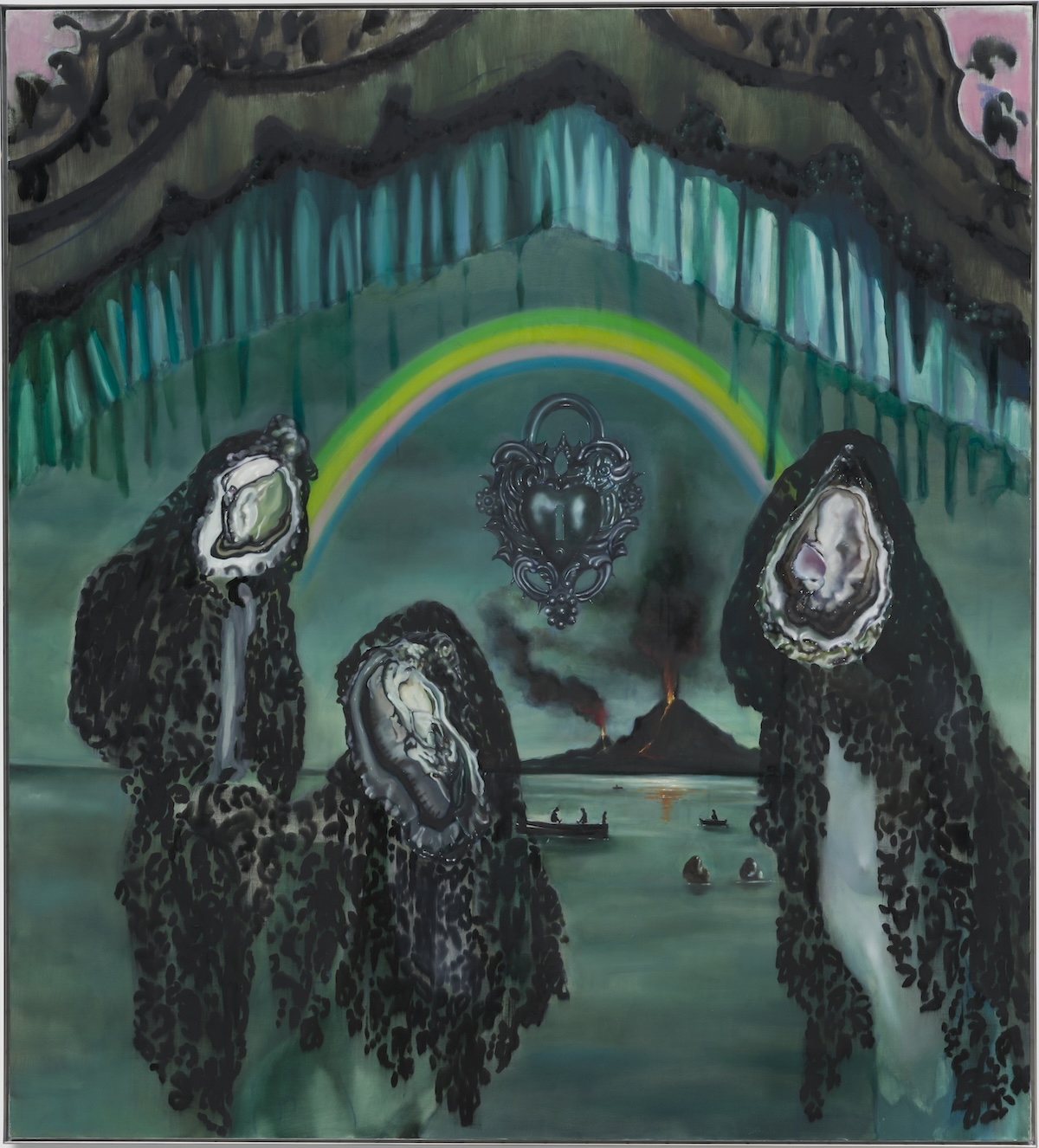

I love this notion of the great return, and I symbolize it with shells, with water, with oysters—which, of course, could be interpreted as female anatomy. It’s like the birth of Aphrodite; it reminds one of coming back to the ocean, to water, to the womb.

Tell me about the books or historical sources that inspired your approach.

There’s this very large, very old book from 16th-century Germany called the Augsburg Book of Miracles. It’s full of gouache paintings of very surreal apocalyptic scenes. There are comets, there are swarms of locusts, there are strange mythological creatures, there are images where it’s raining flesh and blood, there are rainbows. It just has this sense of mysticism, wonderment, and total unease. Nobody knows who made the book—it’s a mystery.

I also read a book called Medieval Bodies, and learned that in the middle ages, there were a lot of interesting parallels being drawn between human body parts and parts of nature. The lungs are like the wings of a bird, symbolizing flight, breathing, movement, and life force. The nervous system and the brain are like tree roots. It goes back to this kind of external, internal relationship between nature and the human body. So I think that’s also where I got a lot of these motifs of shells and barnacles and metamorphosis.

How much are you consciously crafting these layers of meaning, and how much of the work is free-associative?

I’ve never wanted to create paintings that make people feel one singular thing. I think it’s fascinating to let people go on their internal journeys with what these symbols might portray for them. There is a meaning behind everything I do, so there are lots of little doorways to open if one pleases. It’s like a secret within a secret.

For example, Touching the Vessel, that painting with the silver metalwork, is a reference to Betony Vernon’s jewel tools. To me, the work she does is like a metaphor: she’s making these beautiful objects that allow people to erupt in a sense, to open, to break through. These objects are like a symbol of physical transcendence. So they were a metaphor for orgasm and out-of-body experience. And I love that the same motif that conveys disaster and chaos can also be a symbol of pleasure and transcendence.

I’m curious about your own experiences—have you had any out-of-body experiences, or experiences that completely shifted your perception of the world?

Through methods of alternative healing, I have had experiences that made me feel that my sense of reality, my sense of existence in the world, was turned inside out. I’ve had these moments come not just from beauty but from pain. Again, it’s like life cycles: You get these breakages in nature, these massive ruptures, and after that, something transforms. Before the butterfly comes out of the chrysalis, a caterpillar has to turn into goo.

We can’t live in a state of eruption or transcendence all the time; it’s always going to be temporary. But human beings are constantly being led by the longing for a feeling of spiritual openness and enlightenment. When I think of this human longing, of searching and looking for a sense of eruption, there’s also a great vulnerability in that. Every time I’ve had these experiences of rupturing and healing, it always came with a torrent of grief. That’s also where I get this term from like expulsion: this sense of being cracked open. Loss has led to the most painful and the most beautiful transformative experiences of my life. There’s an analogy I always think of: somebody gives you a set of hot, rusted keys, and nobody wants to hold them because they burn your hands. But then when you do hold them and sit with the discomfort til they cool, you can use the key as a tool to open up new parts of yourself.

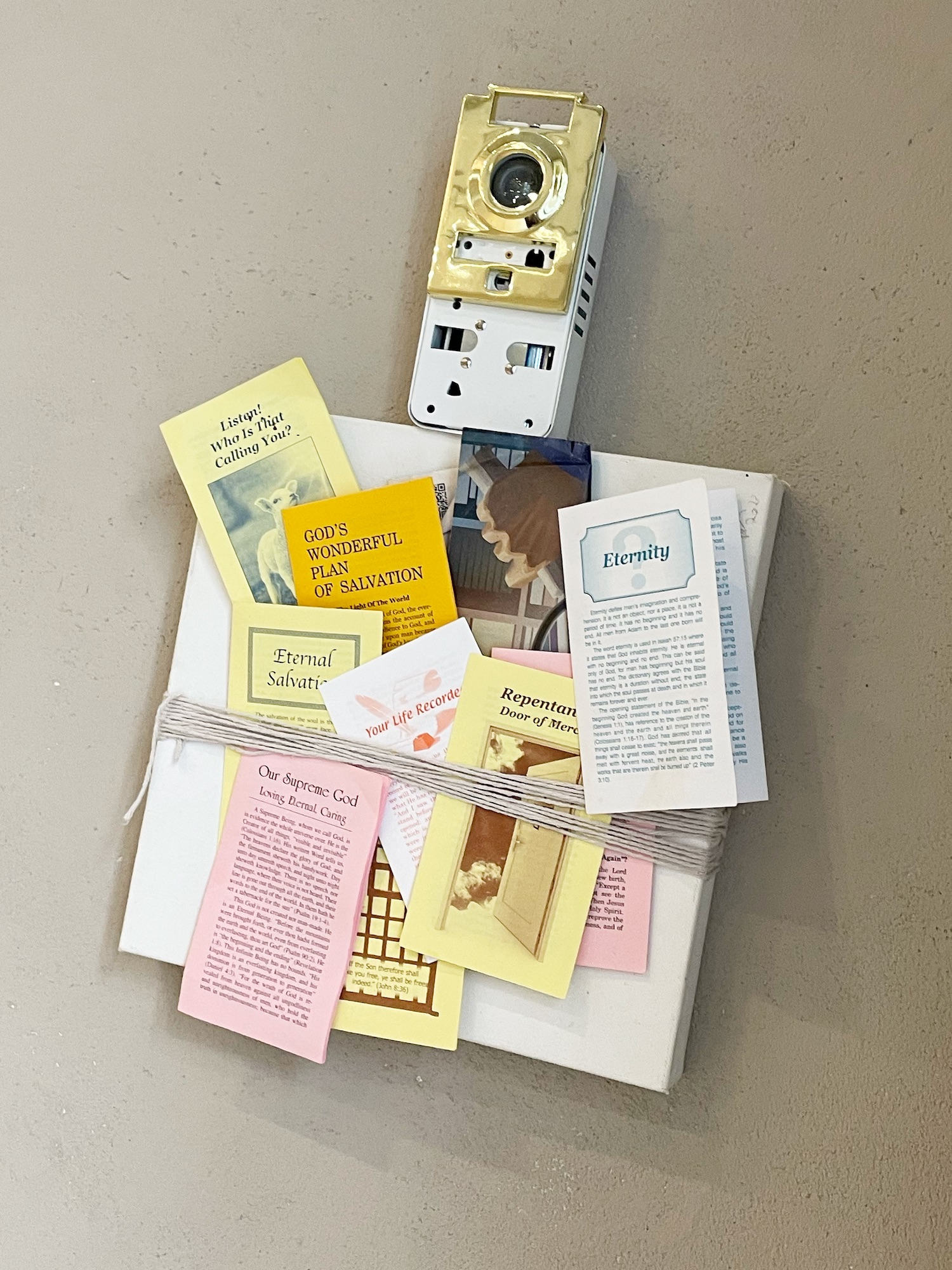

You said in another interview that you’re attracted to vessels and objects that have these connections to other narratives. Could you elaborate on that?

I find it fascinating how human beings try to connect to spirit: this striving to feel more than body, more than mind. I’ve always been enamored with objects of worship—how as humans we create these shrines. When we all collectively put energy into one object, projecting all this thought and emotional dependence onto a material thing, it’s like a form of magic—it almost comes alive. It means everything, but it also means nothing. Similarly, these paintings can mean so much when I’m doing them, but they also mean nothing; they’re just pigment on canvas. There’s such poetry to that, and it also relates like objects of worship: How much potency can you put in one piece of material?

My work as a painter is such a private experience; I’m someone who gets addicted to being alone, and I’ve had, in the past, obsessions with building little shrines and sitting with objects and collecting trinkets, treasures, remnants. And there are also portals to at least make us feel like we are traveling to another realm. New age groups use holy water, like in ancient cultures, and I think it’s beautiful—but there’s also an element of make-believe, a childishness to that. And I think perhaps that’s why my paintings carry a sense of unease but also belief, wonderment, and a bit of madness as well. I wanted the show to be a journey, almost like a fairy tale: how there are moments of beauty and sacrilege and fear and perhaps a little bit of horror. I want it to feel like you are in the midst of a spell.

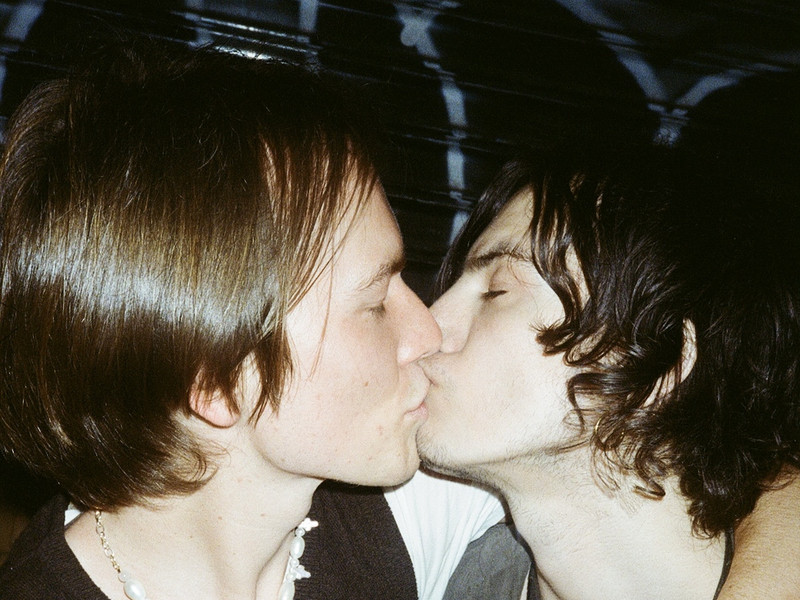

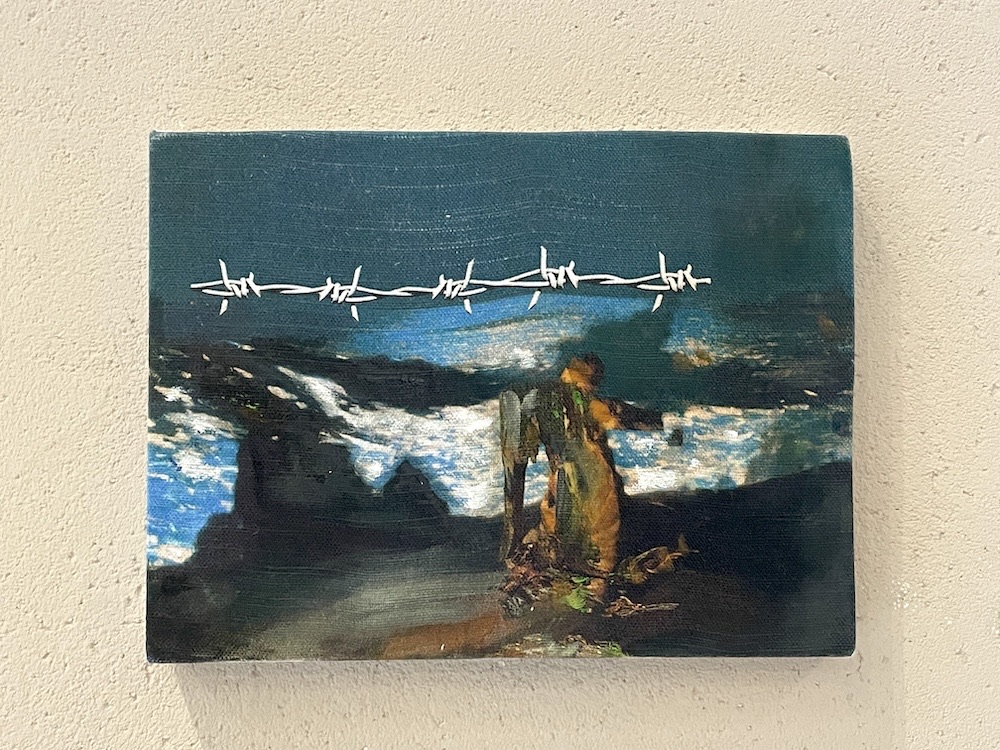

Left: Love Belt, 2023

Right: Warm Chains, 2023

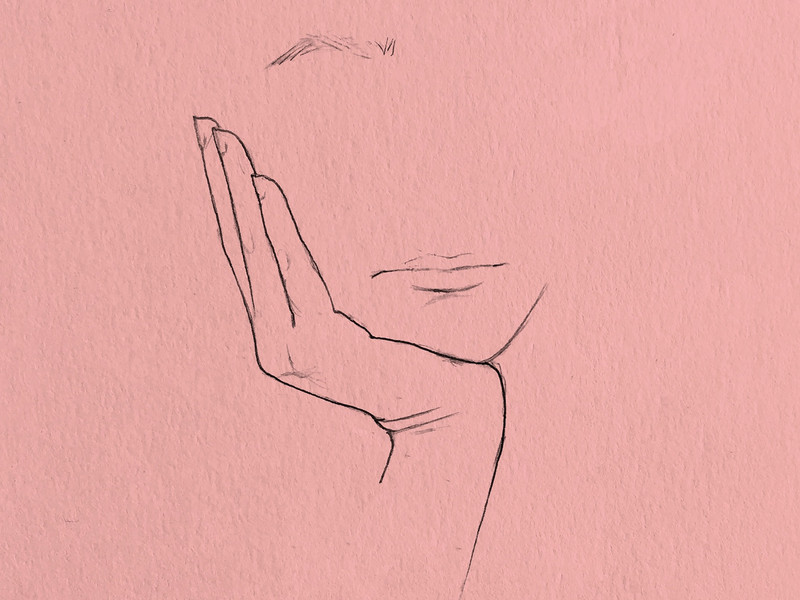

Left: Fool’s Arcadia, 2023

Right: Vial, 2023

Your paintings are so dreamlike they make me wonder: What are your dreams like?

When I was a child, I would be extremely taken by my dreams. I had different phases of sleepwalking, where I would walk around my house with my eyes open. Sometimes I would even wake up and be conscious, but I would see everything [as though I was] still in the dream—all my visuals were in a different place, but at the same time, I was coherent. One time I woke up and I was very much convinced I was Alice in Wonderland. I even woke my dad up and said I don’t know what to do, I’m growing out of our house! I remember being quite embarrassed about it. Another time I was walking up and down my house, and I couldn’t stop moving my arms. It was almost like Sydenham's chorea, that jerky kind of bodily illness at the turn of the century.

So yeah—lots of things have come out in dreamtime! I think dreams are so interesting, and kind of like painting: a process in which the psychological phantasmagoria of daily experience is regurgitated. When I would sleepwalk as a child, I was between a state of dream and conscious reality. And it goes back to these spaces I love: the in-between space, the void between two realms. Most of the paintings, if they’re in a landscape, it’s always twilight. It’s my favorite time, that space between night and day, between the lightness and the darkness. The day’s ended, it’s already like a faded memory… It’s already happened, and you can’t go back to it—and then it’s the mystery of the night.

Tali Lennox: Tremors is on view at Nicodim Gallery in Los Angeles through April 6.