Trials, Tribulations, Penthouses And Pitfalls

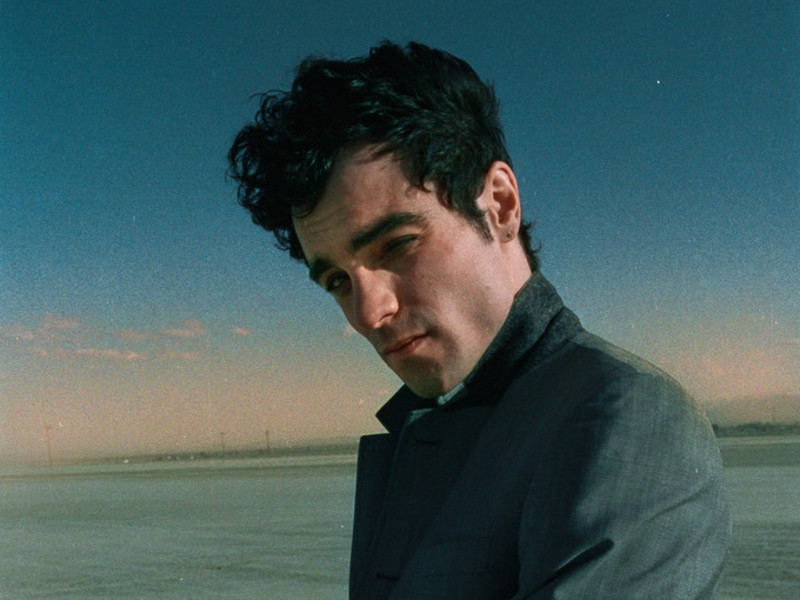

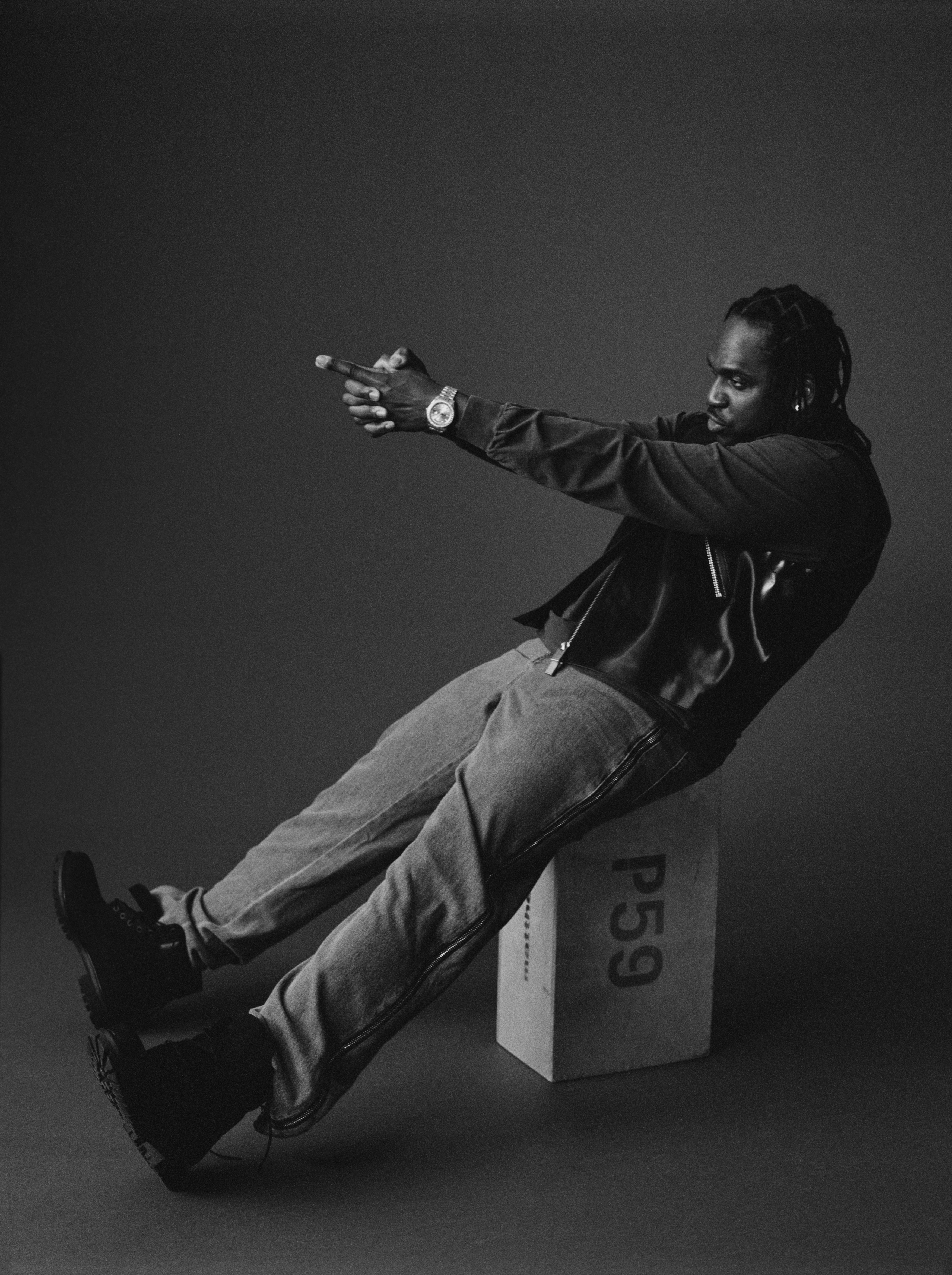

Shoes TIMBERLAND, shirt, pants, and quilt CARHARTT WIP

The rapper/mogul/entrepreneur Terrence Thornton has never been one to show his hand immediately, if ever. He releases years apart, on his schedule, shying away from the craving to be overpresent with his peers. Last time he rolled an album out, 2018’s acclaimed DAYTONA, he did so during a skirmish with one of the world’s biggest artists, and claimed the spoils of victory by unearthing his opponent’s unborn child. His oeuvre, whether solo or as one-half of the brotherly duo Clipse, finds Thornton excavating the innards of a sinister world from a stove’s-eye view. There’s vengeance and repentance in tales from a Black Virginian, oscillating between kingpin diaries and high anxieties. It’s all survival, told with thrilling detail; memories become meticulous, and the myth grows louder with every flake of snow.

But where is a man lost in myth? So palpably removed from his circumstances, yet one step away from the familiar. For Thornton, there is intention and a clear separation. Pusha T embodies the streets for those that survived the likes of Reagan and Nixon, while staying tapped in with the times since the streets only change so much. He’s an audible Godfather, prestige street rap as his legacy precedes. Current, but not chasing. Never flinching. Not to mention, retaining an unrelenting desire to be in the best of his class. He’s touted the upcoming album as his masterwork for months, reuniting with Ye and The Neptunes for another serving of first-person testimonies. Made in the pandemic, Push even surprised himself by what magic he conjured in the world’s vice grip, movement limited.

Left: Coat RAF SIMONS, pants DIESEL, shoes TIMBERLAND. Right : Jacket and pants CARHARTT WIP

A core concept of your fandom is consistency, to the point where you're in-between album cycles—you're dropping singles, there would be rumors that you're about to drop again—and people say shit like, ‘This nigga ‘boutta drop 12 more songs about cocaine… and I'm gonna listen to all of it. Like, I'm here for it.’ For two decades now, almost, this image is just still endearing to folks. How does this legacy feel right now, to be where you're at and still be able to come back whenever, and have a bunch of people ready to hear that shit?

Man, I think that is the most enjoyable part of what we're calling my musical career and legacy: the fact that I make this music on my own time, I drop this music when I want. The fact that people have tuned in to my consistency and they respect it. I really love the idea that I'm making the exact music that I want to make at this point in my career, with absolutely no compromises, and I think the most rewarding part is that my fans actually want simply just this. And I appreciate it so much, man. I think it's the greatest reward of doing this. And I've been in this game a long time, and it's like... I couldn't imagine having to or attempting to make different kinds of records, just trying to conform. I couldn't imagine trying to do that at this point in my career, and I love not having to—I liken it to Martin Scorsese, man. You never ask him. He makes The Departed, he makes fucking Goodfellas.

He's not gonna make Hitch.

Exactly, and no one ever asked him to, and it's so crazy. It’s so funny, because in-between album cycles, you hear people on Twitter or people who want to actually be funny, they'll say things like, ‘Oh my God, here he comes with this again,’ blah, blah, blah, blah, blah… By the time the first record drops, or by the time they get a sneak peek of what I'm cooking up, everybody's ready for street music. Everybody. They don't want anything else, and they love it.

I feel like, especially in rap, there's two—well, not to be too simplistic, but there's two general archetypes. Especially when you're talking mainstream status, there are folks that, when you look at their oeuvre over time, they can make seven albums, and all seven of them sound different even though there are themes that run throughout people's work. And then there are certain folks that build that run on consistency by finding their corner market and just doing that. And it'll deviate based on how the times change sometimes, based on how you grow, based on how you want or don’t want to respond to things, but at the center of it, it's coke rap, and that's what we're doing, no matter what we're doing it on.

Yeah, and that's very important that you notice that—that it does change depending on the times. It always sounds current. It don't sound like fucking “The Message” from Grandmaster Flash & Melle Mel! The shit always changes because the streets are always changing, and the times are always changing. When you're tapped into Pusha T, then you understand culturally... I’m telling you this street music lives on, and it does change with the times, and the streets aren't really going anywhere. So, it's never the same thing to me; I don't look at it the same at all, ever. It's always a different perspective, a different take on what's going on outside.

Right. I was going to ask you about just that, because when you've built such a high profile being the specialist that you are, it's almost as if folks are waiting for you to either deviate a little too far, or to get stale, like, Oh, here this nigga go again, like you said. So, the traps look different, but it's a trap. A brick's gonna be a brick; the price might be different, might be cut with something else… It's still a brick. How do you challenge yourself to find new takes on the same subject matter to keep yourself interested?

Man, I think that... You mentioned the term ‘coke rap,’ right? I've always felt that coke rap was a cheap take on the genre. If you're a surface-level listener, then it's coke rap, and to me, I look at it as cheap. If you’re a real listener and you call it coke rap, I'm like, You know what? You're just trying to find the quickest way to describe it, whatever the case may be. But, at the end of the day, I feel like the title and the drug references are the seamless thread to get you [through] relationships, perspectives of the street nigga, the fucking codes, the ethics. It gets you through all of those actual nuances, from point A to point Z. But really, you're actually traveling through the mind and mentality of women in the streets, guys in the streets, how a person really looks at how that mindstate works. I spend a lot of time in Virginia—where I’m from—and in the area in which I grew up. And I really still have friends that are still affected, whether they're incarcerated right now, or in the streets right now. Man, it's never too far... It'd be nothing to stick my toe back in that pool, you know what I'm saying? It's so right there. So, I feel like I have the consistent, continuous cliffsnotes of life at my arm's reach. I feel like people hear it. And then on top of that, just being outside. The funny thing about it is… This album was created during the pandemic, and it's so good, and that's the one thing that I’m shocked about. The fact that it was created in the pandemic, and where I couldn't always pull from me being outside and being in the mix... Because there was no outside. I have surprised myself in how great this thing is. That is the biggest takeaway for me personally, the writer: like, Oh, this shit is incredible, and how? How did my brain really, really, really work this without having the Friday night at fucking such and sucha club in the biggest city, or whatever the live city is? Or not running to my guy Rugs's black party this year in Atlanta and shit like that, you know what I'm saying? I wasn't even in those mixes this year—for the past couple years, actually—and the masterpiece is still that: a fucking masterpiece.

Left: Jacket, top, and pants CARHARTT WIP, shoes TIMBERLAND, jewelry TALENT'S OWN. Right: Coat RAF SIMONS, top MARTINE ROSE, pants DIESEL

So, just for reference, I'm from PG County, Maryland, from Fort Washington. So, that's not the trenches at all, but you hit that 210 highway, you take one turn, you aren’t from the trenches. Especially in the DMV, the quarter-million dollar cribs are 10 minutes from the trenches, and you probably know somebody over there or got a family friend or a cousin or something. It's never too far. To wrap that back around, as far as the term coke rap as a catch-all, what we're really describing is the music and the musings of Black people who grew up poor and fucked over by the world constantly. That's what it's about; cocaine is the entry point.

Yeah, for sure. It’s funny, man. How old are you?

28.

So, I'm actually doing a [film project]—I'm executive producing it with Kenya Barris—and it's about a man by the name of Curtis Malone, who spearheaded AAU [Amateur Athletic Union] in the DMV. Got a lot of guys in the league, and at the same time, he was hand-in-hand with the cartels, and he ended up going to jail and so on. It's funny that you say that this is how people were fucked over, because we were having a creative call the other day, and we [were discussing] the intricacies of what was going on during that time or whatever. And everybody was just breezing over and sort of just talking and trying to make light, and trying to find these very heartfelt ways of describing the time. I broke through the conversation and I said, ‘Hey, listen, man, it was the fucking eighties. It was the eighties, early nineties, and it was crack. It was the fucking gold rush.’ And when you look at the Rockefellers, Rothschilds, Kennedys, and all of those big, huge families, what did they start their fortune off of?

Slavery, probably.

Then after that, they went into fucking liquor and other things at the time—illicit and illegal business—and they went on to become the fucking powerhouses of the country. I said, ‘For real, that shit was young Black kids fucking getting rich, and getting rich quick. And I look at it no differently than those families.’ We were the only ones who were fucking singled out, you know what I'm saying? Like, Nah, we gotta stop this, we're gonna single-handedly destroy a generation, and target them, from prison to drugs being placed in the neighborhoods, and so on and so forth.

I'm glad that you take that away, because I'm really just giving you the mentality of that kid from then to now, because the hustle was our fucking gold rush, bro. For us. That shit was merely mischief during that time, during my era when I went outside. We were really gambling with our lives, you know what I'm saying? It was purely, purely mischief… And getting money. They waged a war on us… And they had been waging a war on us since the eighties.

‘The crack era was such a Black era. How many still standing reflecting in that mirror? Lucky me.’

Lucky me. Right, right, right. Listen, I heard you and I was like, Wait a minute... My verses be so edited by Kanye, because it was more bars after that! He be like, ‘No, man, you goin’ too far, aghhhhhhh!!!’ MP—So, look, I wasn't as engrossed in the culture when Clipse was making their run. The most that I remember’s that everybody would do “Grindin’” on the fuckin’ lunch table. Everyone. *Drums table with his fists* That's how you freestyle at lunch. I remember that shit, I remember “Mr. Me Too” and all that, but I listen to that as a grown man, and it's like... You talkin’ ‘bout how ‘them crackers wasn't playing fair at Jive,’ right? So, that guy saying that, to you being head of G.O.O.D. Music, what have you taken from your experiences to lead you to be a good business person, to have good dealings and to evolve as the game evolves so quickly?

Well, for G.O.O.D., and my involvement, it was all about relationships and trust. I always kept a good, neutral relationship with everyone at G.O.O.D., meaning artistically, and I feel like Kanye took notice of that, and of me being tapped in with new shit. We got the “Don’t Like” remix, which, people don’t know, we were actually tryna sign all of them from Chicago, from Chief Keef to Lil Durk to everybody. That was my play: myself, and Free Maiden, who’s like GM over at G.O.O.D., works on Ye’s management team. I was working on Cruel Summer, and we came to New York. We were just kickin’ it—Don C was there as well, I believe—and Ye was like, ‘Yo, man, what’s hot? What’s new?’ And I was like ‘Shit, don’t ask me what I’m listening to… ‘Cause I’m gonna pull up some shit.’ He was like, ‘Nah, just pull it up,’ and I pulled up “3Hunna” from Chief Keef. I pulled it up, and this joint is going, “Don't Like.” I was like, ‘This shit about to go, this gonna snap.’ It might have been moving. It was early, though. Me and Free was like, ‘Yo, you know what? We should sign all of them.’ And I was like, ‘No, dog, you've got to sign every last one of them, too. They got this producer, Young Chop, he just needs to do all their beats. It ain't even no heavy lifting. You just let them do they thing. It's going to look dope because you from Chicago, they from Chicago. It's the youth.’

By the time we’re trying to make the deal happen, they started catching deals. Durk might have caught a deal. Keef caught a deal. I actually took Durk on tour with me. I was like, ‘Durk's the star,’ because he had this record called “L's Anthem” that I was a huge fan of. But with that being said, I think Ye was like, Man, bro, you tapped into shit that I don't catch until a little later. We were just into new energy and shit like that.

It's crazy you gave me that whole section of history, as I'm sitting in Chicago in my living room right now.

Yeah, man. What would've happened if we had that whole collective? What the fuck would've happened, man? And they were just killing and ripping up the underground, eventually turning iconic, as you're looking at Durk having his moment and shit. And that's not even a given moment. That's 10 years. It's really dope to watch him, specifically, because that is something I saw.

Yeah. Now he’s sold out the United Center. He's gone. And Keef’s like a cult figure where he's still been able to get insane hits without having to play the major label game, too.

Yep. 1,000%. It's great. And you're looking at them on two different spectrums.

Let me ask you this: hip-Hop comes from poor Black folks, from niggas who ain't had shit making shit from what they had; didn't have instruments, plugged in turntables, borrowed people's records, flipped that shit, got on the mic, start the party. So, in theory, if a world without poverty is attainable, what does a world without trap music look like? Because if you take away the conditions that facilitate that, where niggas don't have to fight each other, struggle, make choices that they probably shouldn't make, what does that condition look like when there's no trap music? There'd be no need for it, right?

Left: Jacket KENZO, jumpsuit SACAI, shoes YEEZY X ADIDAS. Right: Jacket NOSESSO X LEVI’S, jewelry TALENT’S OWN

Man, I feel like, just the way the world is set up, man, there always has to be a pyramid or hierarchy from top man to the bottom man. And if you're ever on the bottom, there's always going to be some level of hustle that's going to present itself for you to come up out of that. And when you're on the top, you're always going to try to keep that lower level down below you. So, there's always going to be some level of oppression, always, which means people are always going to struggle to get out of it, by any means necessary.

Do you feel like a world without that is impossible?

Yeah. I feel like that's impossible. There's too much greed in this world for it ever to be like… Yo, the world you're talking about is something that's built off just fair and fair distribution, and you have to put all your trust in the greater good of humankind and America. And that is something that is just—they don't even sound great together. It doesn't even sound real together.

It's impossible. But I do think America could come to an end. I think that's possible. I think a lot of shit has to happen, but I do think that's possible, because I think the alternative is, well, shit, we're stuck.

Yeah. I mean, hey, I don't know. I sell a lot of dreams. But I ain't selling no dreams on America. None.

In the past, you've spoken about having to find and source the energy you have when you're not in that certain position. ‘I am just a short stone's throw from the streets.’ But you also source the pain and you're still losing people, to this day, from this exact same shit. So, what is it to pull from your psyche, to pull from your heart that much? How do you manage to endure for so long when you've been so far removed from the street, but shit is still happening?

I don't know. It's my life, honestly. I don't even know that I'm enduring anything. This is my wake-up to my bedtime. This is life, as I know it. I can't imagine a day where I'm just not in tune with what's going on in the streets. Again, I'm just surrounded by my friends; my whole life has always been two sets of friends. And I, damn near single-handedly, bring them together. It's like a friend in the street, and my friends in music—everybody might have known each other or known of each other, but I am the common bond that is like, Oh, we are family, and we're going to connect and do this together. And with that comes trials, tribulations, penthouses and pitfalls. Shit.

Something that I love about the way that you approach what you just spoke on, the best rap from this subject, to me—or just period, no matter what you're talking about—you’re gonna tell niggas, like, I do this shit. But that doesn't come without the consequences and the human cost, right? Because just being Black, being niggas, we're hyper-surveilled at all times, be it our own cell phones, the shit we do, what the state wants to do, people asking questions like they’re trying to get you entrapped or some shit. When you've built your career on this, where is the room for empathizing when the dope man becomes an icon? Do you feel like people truly see Terrence through Push, or are you not even interested in that conversation because Push has to be Push so Terrence can be Terrence?

Honestly, I only want my son to see Terrence, and my family. And if you know me, or get to know me and you see me, you can read through my life. Whether it's online, or just what people would know of me, you'll get your glimpses of Terrence. I, personally, want you to enjoy Push as your escape. Bro, I'm the novel, bro. I'm the novel. I'm the fucking Godfather trilogy. I'm everything that people do… Listen, bro, I'm sitting home today on a Sunday, just catching up on fucking sitcoms and TV shows, just for no reason. I won't even remember them after I go to sleep, but for now, it's just a good escape and a way to just enjoy my day. And it just happens to be that I do music, and I choose to escape through music. I am the long drive, front-to-back, gotta listen to Life After Death and I don't skip no song. Ones I don't even like as much, it don't matter because I just want to be that. I want to be that now, still competing; I don't want to necessarily reminisce about anything. I want people, in real time, to love this shit, digest it, let me be your escape. If you made it through the eras and shit that I'm talking about, if it was back then for you, man, just hear it and let that be the catalyst to reminisce and think about those times and those days. And if you in it now, listen to it now and hear me and be like, Damn, man, he's really touching my soul with this shit. That's really all I'm in it for. I'm really trying to be now. I've been the realest nigga in the room for a lot of years, a lot. I want to entertain with what it is that I do. And I feel like that's the difference between me and other rappers. I'm like, Oh, you're not entertaining me. And I think you have to take some of your ego out of it, because there are some great bars that may mean the world to you, but they're not going to mean anything to anyone else, and I want to get past that. I want people to key in on everything that I say, and actually just love everything that I say. I mean, I've been that guy. People know my ins and outs. They know my trials and tribulations. They know everything I've been through. It's through music. And I feel like I'm in such a good place, but I'm in a creative space and I need to really just hone in on that and stay creative, like such.

Cloak NO SESSO, jacket and pants NO SESSO X LEVI’S, shoes TIMBERLAND

Something that really threw me was when “Hear Me Clearly” came out. You said Pharrell heard that, said ‘I don't want you to be a mixtape rapper,’ and then y'all niggas started working. Which is crazy, because I like this song. But I remember back during Darkest Before Dawn, you would say, ‘I don’t like back and forths with Puff ‘bout rap shit.’ You take criticism very well. How have you, as a collaborator, learned to take criticism from your peers? And what do you offer as a collaborator that's useful criticism so everyone can be the best when they're working on your shit?

No, listen, I take criticism very well, because I understand that I am in the studio with geniuses at what they do. For real. I know Kanye West is a genius. I know Puff is a genius. I know Pharrell is a genius. Know it. There's absolutely no way this side of Hell would I not listen to anything they say, and I would feel slighted if they didn't voice opinions. Now, the difference between why we get the best out of working with each other from me, I believe, is because I'm not an undying fan. I feel like people get in the studio with P and they'll just do whatever he says, because it's P and he said it. And I'm not like that at all. I feel like people get in the studio with Ye, it's the same thing. And I feel like I push back. Because I only want greatness from them. I feel like I'm cheating myself if I get anything less than greatness, for real. I feel like that tug-of-war really is a really important part of how a DAYTONA comes to be and how the new album comes to be.

Being a legendary genius doesn't mean you're incapable of being wrong.

Oh hell no! Muhfuckas be wrong all the time, are you kidding me?!? And they know that. Listen, they know—they know—when they're wrong. And listen, I'm a reminder. I'm a ‘I told you so’ ass nigga. I'm that guy!

With a long memory.

Yeah, no for sure. For sure.

So, the album's half Neptunes, half Ye, just about. The Neptunes, you have a very strong oeuvre; working with Ye you have a very strong oeuvre. Those catalogs and those people, those entities are all in conversation anyway. But how did you make sure the ratio was right, the different flavors were in place for the album to make sure it all worked together?

Well, I don't like long albums—at all. And if I did like one, it would be because it's a double album that you really took the time to make, and not throwaways, you know what I'm saying? I feel like people be giving throwaways, and they do these long albums to... You get to talking about algorithms and shit like that. I really don’t, so I just pick the number, and I actually created a lot more records with P. And when I started trimming down what I loved, I was at six. And I was like, Okay. And then I had maybe two or three already with Ye. And I would just be like, Yo, I need three or four more. And then we just started really putting it together. And it was dope, because those guys like me for two very different things. Kanye wants a bar fest from me every time—he wants bars and he wants a very filthy, arrogant perspective just all the time. Pharrell, he kept using the word composition. ‘I want to make compositions.’ And I was like, Okay, which is kind of hard, because he looks at songs very formulaic: hook, bridge, flow, words, you know what I'm saying? Everything has to really be seamless. And my point was, I don't mind doing that, but every piece of your composition has to have steroids for me to be happy with it. And in his world, dog, he does pop records, all type of shit; you can just give a meaningless chant and that works. That don't work in my world. So, I was like, I'll turn all of my street songs into just that. But I'm talkin’ ‘bout every one of those different layers—or parts of the composition, let's say—has to have steroids in it. And when I say that, I mean, the melody has to be just as sticky as the words, and so on and so forth. I did a lot of doing what I was told in regard to the attack on these songs; how I came at them cadence-wise, a lot of that this time. Because once I started doing that process with Pharrell, I carried some of that over to Ye. And I was like, Yo, b, what is it? I mean, I like the beat, but I don't just want to rhyme it straight. You know what I'm saying? And Ye’d get in there and be like, ‘Man, I hear you on this shit. You don't hear yourself on this?’ And then he'd mimic me with hums and—“Diet Coke,” he one-for-one mimicked who he thought I was. And was like, ‘Dog, this is you, ahh.’ Because I didn't hear that beat at first. And I was like, ‘I mean, it's cool.’ He was like, ‘Nah, when you get up there, you gonna be like…’ And he just started humming and just it's like, gibberish. He doesn't say anything. I did a lot of that, and I'm so glad, because there were times where I didn't get the beat with some of the Pharrell joints, and he'd be like, ‘Nah, man, I'm telling you this shit fire.’ We'd just be going back and forth.

One thing I do out of respect for both of them is to go through whatever their process is fully. And then I'm like, I hate it or I love it. Because you don't understand, a song may start off one way, and then when you go through the full process, they hear something and they're like, Oh no, wait a minute. I'm going to strip all this down and just let this go. And you got a whole ‘nother monster.

I know we were speaking on this concept earlier, where it's like, as long as America exists, it's fucking impossible, right? But like you came up ducking charges, ducking 12, you made “Sorry Nigga I’m Tryna Come Home.” Do you feel like there is a world where we don't need the cops or prisons? I know you're not a politician, but as somebody who's really lived this shit, I'm just curious if you think that world is possible?

Nah, man. There's not a world where we don't need cops and prison because people are just... Bro, it's just deviance all over this place. This place is just fucking deviant, man. Like, people are just deviant and fucking off and crazy. Me and my situations in life, and my predicaments that I've been in, and just the whole drug culture and shit like that—that's just one aspect. And even with that being said, it's like, man, right is right, wrong is wrong. And you gotta be able to own up to your rights and your wrongs. On the flip side, there's the unfairness and the unjustness that comes with us and Black people in the court system, which is totally wrong. But that's just one aspect, bro. It's all types of wild out here. It's all types of wrong out here, and some of it definitely needs to be addressed.

Has your brother heard the album? What does he think?

Oh man, he loves it. He really, really loves it. And he doesn't listen to much. He definitely heard the album numerous times, even was in on a couple of sessions, and just was like, Wow, this is crazy. His last couple calls were like, ‘I like Pop Smoke, I like King Von.’ Or he'll send me something fresh from the battle circuit, like, ‘Yo, he was really goin’ in.’ I think that's where he’ll casually stumble upon certain music or whatever. But we just had this conversation the other day, and he was telling me how he doesn't like how the streets are fully following these kids into the music. He was like, ‘Man, I actually liked Pop Smoke and King Von, and they both died, and I don't understand. And they were good. I love to believe them in their raps, but not so much that I want them to die.’ And he's 1000% not a fan of that. And he's just like, ‘Yo, the kids ain't learning, or they don't have the people around them to sort of make some of those right turns instead of turning left, to where you'd have to end up at your demise.’ I found that conversation very telling, coming from his perspective, and I agree with him totally. Because these kids are out here really getting money, and really getting to it and finding superstardom, only to die. We were like... It was like, Biggie, Tupac. You know what I'm saying? And I feel like after them, we had learned a lesson, like, Wait a minute. And I feel like now I'm sort of seeing that lesson get a little lost.

Jumpsuit SACAI, shoes YEEZY x ADIDAS

Left: Vest ALYX, top CARHARTT WIP, pants DIESEL, boots TIMBERLAND, jewelry TALENT’S OWN. Right: Top CARHARTT WIP, pants MARNI, shoes TIMBERLAND, hood DINGYUN ZHANG X MONCLER

Niggas not learning the lesson. We keep seeing the lesson every week ‘cause somebody else is getting in their city, in Cali, wherever. Every other week, it’s somebody else. So, I spoke to Killer Mike before, right?

Wow. Bar. Yeah, spitter.

And he said when he listens to street music with his son, even his son knows when niggas are suckers or not. And Killer Mike said, he would rather young niggas—maybe they're from the suburbs, maybe they from around the hood, but they weren't outside—he would rather young niggas make music with the aesthetic of acting like they in the street, and not be in the street, and get money, than actually have to be in the street and do it the other way. What do you make of that? Because like, there's consequences to this. People die. Push, you’re one to say ‘Fuck all these fairytales,’ and ‘Your numbers don't add up on the blow.’ So, when you see young niggas taking a lifestyle because it's popular and it'll get them a hit—might get you signed, might make you pop because people pay attention to that—but you don't come from that, what do you make of that?

Personally, I feel like these are the perks I'm afforded, and I'm able to say those things because I've been there. Right? Like really. At the end of the day, rap competitively, for me, has to tap on whatever is. Just because of my era—I'm from the time where you had to have it, buy it, spend it, go get it, you had to show it. I'm not really from the time of like, I just get to know about it because it's on my phone, and you can be just as cool. Like, be broke, girls won't date you… that was true for then. It's not for now. So, we really had to get out there and really risk it all to just have regular shit going on, like regular teenage, late-teen shit happening.

Regardless of what I say, I ain't wasting my time pinpointing who's real and who ain't. I'm cool on it. I've been through it, I've been through the wars with it, too. You know what I'm saying? Like I've done it, and… It's a new day. Those staple rules and shit like that—shit that would've destroyed you in previous years—are shrugged at in 2022. Like, I don't want to be the police for it. Fuck it. It's all good. I just want to be the best I can be. I'm running a different race: I'm trying to see how far and how competitive I can remain as the times change, as the eras change. How good is this music? How can I keep elevating this music, and how can I keep pushing it forward? I don't want to do reunion-type things for a while. I don't want to go back and do shit like that. I want to see how far this shit goes. I want rap music to be—my age bracket is the era to see who's going to be our U2, you know what I'm saying? I guess Hov is going to be like the touring Rolling Stones, right? Like, he would be the one who's made it to that level of just iconic. But it's only one. I want to be part of that legacy. And I think there needs to be more of us, so we can see [them] like [we] see the Rolling Stones, see Phish, see U2, see the Grateful Dead, see all of these rock bands become great. Rap is the youngest genre, so I want to see rap have those same types of Mt. Rushmore-level acts. I want to be one of those. And I want to be out here for a very, very long time doing it at a very, very high level until I just don't have it no more. And that's cool. And then I'll start on my fucking Best Of performances and shit.