Hung La: On “Fitting In” in Luxury Fashion

I never saw my skin colour as different growing up. I was aware of my difference, but never saw it as a reason I could not fit in. I grew up in the 80’s in a comfortable American suburb of Washington DC. During the week, I was a shy teenager navigating school and carving out my own space in a predominantly White American environment. On the weekends, I was immersed in my Vietnamese roots, with a countless amount of community gatherings and copious amounts of food. It was a clash of two different worlds, each one with different rules and different codes. Clothing was a tool not just for assimilation, but also rejection of the traditions of my past. My grandmother was a seamstress and pattern maker back in Vietnam; after she immigrated to the US, she would make beautifully cut clothing for us as we grew up. At school, I would walk down the hallways in a full-black look, sporting wide leg and extra-baggy raver JNCO jeans, a cotton canvas belt, a Red Hot Chili Peppers concert tee in XXL and a fitted baseball cap, worn backwards.

Like a good Asian son, I started college with a major in Computer Engineering. It quickly became obvious that path was not the right fit for me. Despite not having any formal art training, I worked to prepare my portfolio to study Fashion Design at Parsons, Istituto Marangoni and then the Royal Academy in Antwerp where I completed a Masters in Fashion Design. After my Masters degree and through some friendly connections, I started my career in the studios of Balenciaga under Creative Director, Nicolas Ghesquière, shortly after I graduated from school. I felt incredibly grateful for this opportunity, and I was absolutely committed to making the most of it. I started on the pre-collection team and worked 12–14-hour days 6-7 days a week draping, making trials and 3D design samples. I was the only Asian in the design studio at that time. My experience of being an Asian American man had been one of assimilation; fighting to be included in white circles, even if on the periphery. Balenciaga was not American. It was privileged and cultured and European. Surviving there, and succeeding under mountains of work and endless creative demands, was less about talent - everyone was talented. It was a question of being able to fit in. Twenty years ago, as in many industries, you could count the people of colour in the company on both hands. Looking back, it is clear to see that these spaces were exclusionary towards people like me; at the time I couldn’t bring myself to focus on my race as an obstacle, or use it as an excuse for any setbacks.

I vividly remember feeling like I fit in for brief moments while I was at Balenciaga, but still never being truly a part of the culture; feeling accepted but not exactly one of them. I was allowed in the door, but I didn’t have access to all the rooms. There is a social fabric in every workplace, and in this particular situation I was a minority, and certain privileges were not attainable. For me, the difference between being accepted and fitting in doesn't look like much on the surface, but when you are really accepted there is this feeling of ease and understanding and when you do not, you are always left with these questions of whether you did something wrong. This led to me feeling that I had to work harder just to be treated equally; I can remember being the last one in the studio on many nights.

I felt extremely frustrated every time I was passed over for promotions and work, but rationalised it at the time that I wasn’t the most talented or was not vocal enough. I felt grateful to be there but bitter that I never got the same opportunities that others got. There is a lot of shame and self blame when others get promoted in front of you. Instantly, I would question my abilities or what I didn’t do well enough.

I remember on several occasions being in my 30’s in Paris and walking around and some random dude would just jump in my face and do a karate chop and yell “Jackie Chan,” like that was supposed to be a way of engaging or connecting with me. My experience with Anti-Asian racism has mostly been more subtle. It’s invisible most of the time and barely peeks its head above the surface. We are the “model minority”, the ones that are let in, but not fully. We are included because we work hard, stay in line and because we are not a threat. However, I often think back to joking alongside my colleagues, who would poke fun at my Asian-ness and my heritage. Doing so would allow me to feel as if I fit in with them. At the time, I believed I could disarm them with humour and make light of my racial differences; preferring to be the one making the joke at the expense of my own race first then to have them laughing behind my back. It was a manifestation of internalised racism and a whitewashing of my cultural heritage.

It’s not easy to talk about, since race was not the only issue at play, but looking back I often wondered if being another ethnicity would have changed things. I have spoken to other Asian contemporaries about the Bamboo Ceiling, the principle that we reach a ceiling in our careers because bigger opportunities are not open to us because of our skin colour, and feel like the systems in power are not set up to support our culture in the same way as others. More and more Asians in the West are empowering themselves to break through the Bamboo ceiling.

As my career progressed, I took an opportunity to move to London to work for Phoebe Philo at Celine. I was hired to be the head of the Leather and Fur department. I was up for a challenge and really admired the female centric philosophies of the brand. London, which is more diverse than Paris, offered a new opportunity for me in the design studio. Joining this team, I was not the only Asian Designer, there was another South Asian designer but we were still definitely in the minority. Work at Celine was also tough with long hours and lots of travel. The culture and rules of engagement were different from Balenciaga, but I still sometimes felt the same pain of not fitting in.

I am not saying that either Balenciaga or Celine are inherently anti-Asian. Alexander Wang was appointed Creative Director of the former shortly before I left. Both houses opened their doors to me and gave me an opportunity to learn and work in amazingly creative environments. But we cannot and should not be blind to how few Asians there are in the fashion industry, let alone in senior positions like Creative Director or CEO. So many Asians from all over the world study fashion, and yet these numbers do not translate higher up, particularly in the West.

I cannot say that I have been directly discriminated against in my work in these experiences, but I do feel there are cultural biases and energies at play that we are not always aware of. It acts like an invisible hand pushing us apart and separating us further. And in this awakening of identity and race that I am undergoing, I believe it is our obligation to ask why and to work towards equality. Fashion is now so much about inclusivity, but true inclusivity is about equality and representation, where everyone’s stories are heard, feels a sense of belonging and no one is not forgotten or passed over. Aspects of identity such as race, gender, religion, or sexual orienation are integral parts of us that cannot be separated from our being. They are the tapestry from which we compose who we are and how others understand us.

After leaving Celine, I had the opportunity to start my own brand, Kwaidan Editions, a luxury womenswear brand, with my life partner Léa Dickely in 2017. And this past January, we launched LỰU ĐẠN. We do both brands together.

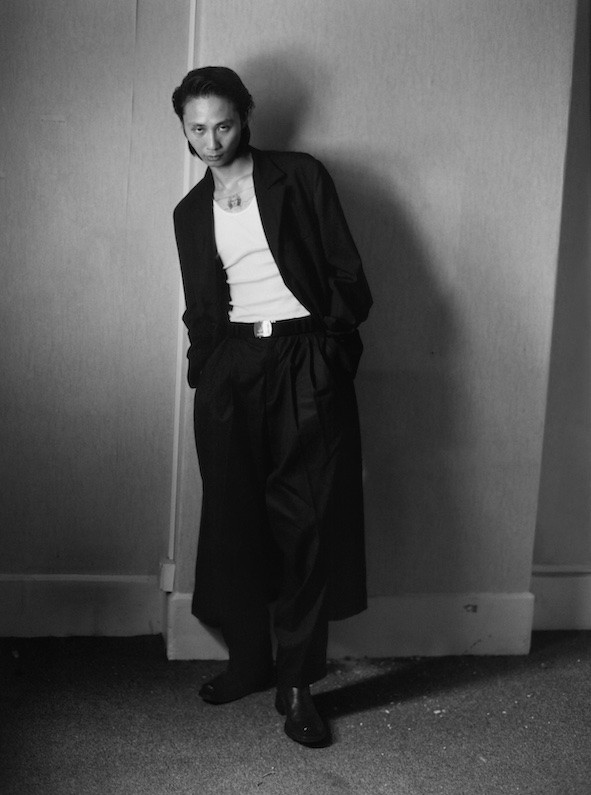

LỰU ĐẠN, which means enraged or dangerous man in Vietnamese, has given me an opportunity to break through my own bamboo ceiling as a designer and founder. Our deepest ambition is telling stories in a meaningful way and spotlighting underrepresented men and women. Growing up I didn’t have many Asian Role Models to look up and the hope is that the generations going forward will have more images that represent them inside and out.

One of the greatest gifts has been connecting to other Asian Creatives who have shared some of the same struggles with their identity in Fashion. Going through these situations, I always felt so alone, but we have realised that these shared experiences are a reflection of our struggles and can also be empowering for others to understand that collectively we can do this together. LỰU ĐẠN is focused on building community as the connecting threads and forging a new brand of masculinity. We recently started an initiative we call “CITY TOURS”, where we tap Asian creatives in cities around the word to tell their stories and have a conversation about their work and life. It is through this work that we are able to see ourselves clearly, uninhibited by the aspiration to be something other than what and who we are.