Miu Miu M/Marbles

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Miu Miu M/Marbles Stool is available for purchase exclusively at the Miu Miu Miami Design District boutique and miumiu.com.

The warehouse, home to Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shisanwu LLC, are both headed by artist and Lunch Hour member Serena Chang—the former being her family’s first American enterprise upon migrating from Taiwan, the latter being her sculpture fabrication studio. On May 18th, within the context of these entities — charged by layered histories of artistic labor, material culture, fashion commerce, migration, and manufacturing technology — Means of Production opened the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse to the public for the first time in its history. The night of performances from a slew of artists, activists, and creatives was just the beginning of an ambitious eight-week exhibition run, which included an art workers’ town hall on June 8th, and an upcoming film program Out of Circulation organized by third Lunch Hour member Lily Jue Sheng on June 29th.

Behind an industrial metal door with vinyl lettering “SHIS NWU” (the “A” has fallen off), I slip into the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse on opening day, the entryway opening into a tiered industrial space full of palettes, plywood, pipes, and metal scaffolding. A thrilling slippage between what is an art object and what is warehouse environs sets in: is an open bag of sweeping compound a work of art? Maybe. The open book on a worktable, or the spectacles on a styrofoam block, with twigs for arms? Probably. Artworks tucked between boxes of hosiery, left unannounced on the concrete floor, or strung up on the rungs of industrial pallet shelves offer an invigorating disorientation.

Works in the show are not clearly demarcated from warehouse supplies — echoing the thesis of the project, which brings focus to the hazy lines between precarious and acknowledged, waged and unwaged labor. To this point, Linh explains, “Our subversive decision to present artworks in a warehouse, rather than a white cube or museum, challenges conventional notions of art and authority. It raises questions about what constitutes art and who has the power to define or value it. This setting infused our project with humor, playfulness, and a sense of freedom — elements that artists and art workers rarely experience today.”

Around 5pm, a group of performance artists begin to wander the entry room with intention, winding small handheld radios while an audience gathers. Performer and choreographer Anh Vo’s Common Fetish calls on a wide list of citations including “Vietnamese possession rituals, Communist propaganda, Nicki Minaj, Jacques Derrida, Christina Sharpe, Thich Nhat Hanh,” among others. At times evocative of a Buddhist chant, a Catholic prayer, a rodeo speech, or a pledge of allegiance, the performers Anh Vo, Kristel Baldoz, Kris Lee, and Nile Harris engage in a call and response. “I am a hole for you to penetrate,” they speak in unison while transitioning from floating independently to a ritual circle. As the procession of performers and audience members trickle deeper into the warehouse, down a dark aisle of boxed stockings, Ethan Philbrick plays the cello in deep bellows and sharp picks. Some clothes are removed and the script becomes darker. Movements become less rhythmic, more rattling, more haunted. The push and pull of performers and bodies, in both possession and dispossession, signals to the interpenetrating nature of the sexual, the spiritual, the psychic, the political, and the somatic all at once.

Artist and writer Amy Ching-Yan Lam then begins a live reading of seven large printed posters lining a hallway near the warehouse entrance, with words based on conversations she has had over the past seven months with herself and others. Equipped with a laser pointer and microphone, Lam reads off “Top 20 reasons why I’m not withdrawing my work or participating in a boycott against Israel or other corporations, organizations, or states that are complicit in the ongoing genocide of Palestinians” in a biting, flat delivery, one of the stated “reasons” being “WHY ARE YOU ATTACKING ME?” Shooting through bullet points, Lam ends on the posters, “Top reasons why I let these beliefs poison my solidarity with Palestinians,” the only reason listed: “I don’t know.” “Top reasons why I don’t know” — “There’s no good reason.” It feels like an apt answer to many contemporary questions we are mulling over.

Deeper within the warehouse, Erik Nilson activates his work Oothecean Stanchion by climbing on top of the pallet shelving unit housing his textured, all-white tableaux of wood, plaster, stuffed stockings, and HDPE shavings. Descending into the work, Nilson begins pulling a chain rig, hoisting a large section of a tree upwards, breaking apart from the chalky installation. Nilson tinkers with piezoelectric microphones, amplifying the clinking and clanking of chains into a feedback of electronic drone, punctuated by the wailing of a small amp on the other side of the unit. He mans a drill augmented with a white branch, twirling and kicking up shavings, finally mixing concrete and water into the mold of a white tree stump. As a sculptor and fabricator, Nilson’s performance echoes his professional work, laying bare the residues of material transformation.

In the back of the warehouse, artist vinacringe enters nude, standing behind stockings stretched across the metal scaffolding of a pallet shelf. A high pitch soundscape falls to a low pulsing hum, transitioning to a breathy narration as vinacringe ties stockings taut across their body. “You have gifted me a wound in the shape of the world,” the audio whispers. In a frantic catharsis, they cut through the stockings on them and the scaffold with a large knife, and on their knees, they send out a yell to release themselves from the performance.

Finally the crowd makes its way to Tianyi Sun’s work Dream Skin (Sheerly) consisting of reclaimed windows from the warehouse, referencing Chinese folding screens (or pingfeng), collaged with Sheerly packaging and hosiery. In a site-specific reading, Sun reflects on stages of production, the working body, and the hidden nature of creative labor, peppered with Mandarin.

Tianyi Sun, Dream Skin (Sheerly), 2024, photography by Tallulah Schwartz

With the conclusion of the performances, we free-wander the dark alleys of pantyhose boxes, soaking in the sense of discovery. The works, too many to name, each address the show’s themes in subtle or oblique ways. Tra My Nguyen’s diaphanous textile-silicone figures, collaged with Sheerly tights, converging realms. silicone dreams, reference histories of Asian garment manufacturing, and especially forms of labor exploitation therein. Especially considering Balenciaga’s recent plagiarism of their master’s thesis, Nguyen’s suspended sculptures summon issues of authorship and the appropriation of creative labor, especially that of BIPOC artists and designers, as well as the opacity of foreign manufacturing to American consumers writ large.

Serena articulates this intersection well: “Means of Production for me, was to engage the conversation around labor. How labor is often deflected onto others (intentionally or not) within our capitalist society. In the setting of the hosiery warehouse and sculpture fabrication, the opposing worlds of mass production and unique sculpture fabrication is the ideal setting to address this conversation. In this age of globalization where labor is hidden and objects can be ordered and delivered the next day, our collective understanding of labor has become so obscured.”

Most crucially, Means of Production offers a refreshing model for exhibition organizing and curatorial method. Really, you could call it a non-framework — built around site-specificity and free-form engagement with it, full creative agency, collective organizing, and a generosity of resources. Every artist who applied to the open call, Lunch Hour tells me, was accepted. The show’s loose concept — applicable to all — allowed for multifarious interpretations. The curators’ and Shisanwu’s volunteer effort fundraising from the public as well as their pocket money largely made the project possible. In Lily's own words, "...so much [funding] is tied up with weapons manufacturers, the non-profit industrial complex, predatory real estate, the state, and mega corporations. It made sense to experiment by self-organizing collectively and in a big way, since that’s how labor power is organized, right?"

The biennial-scale Means of Production ironically feels minimally produced, which is perhaps entirely in line with its mission. In the time of W.A.G.E. for cultural work and growing consciousness of the tentacular ways in which racial capitalism constitutes our contemporary world, the project’s unstructured nature seems perhaps the most congruous response to such questions: in a contemporary capitalist work-relation, how does immaterial labor become economized? How does art and the self become commodified? Are these actually the same question, repackaged?

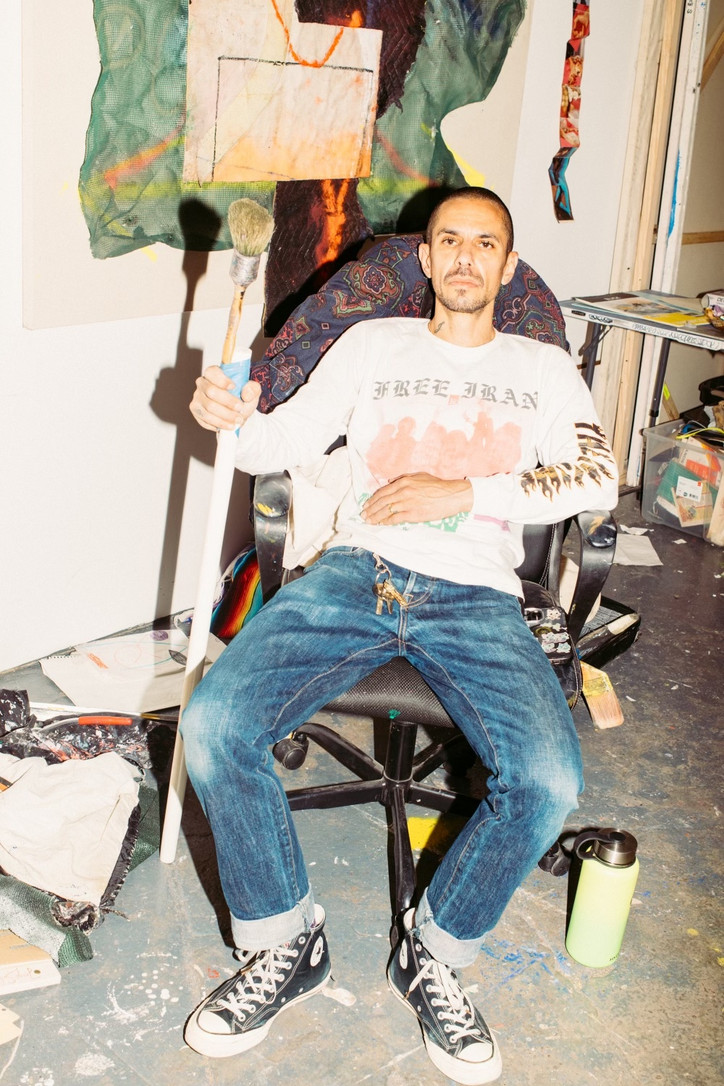

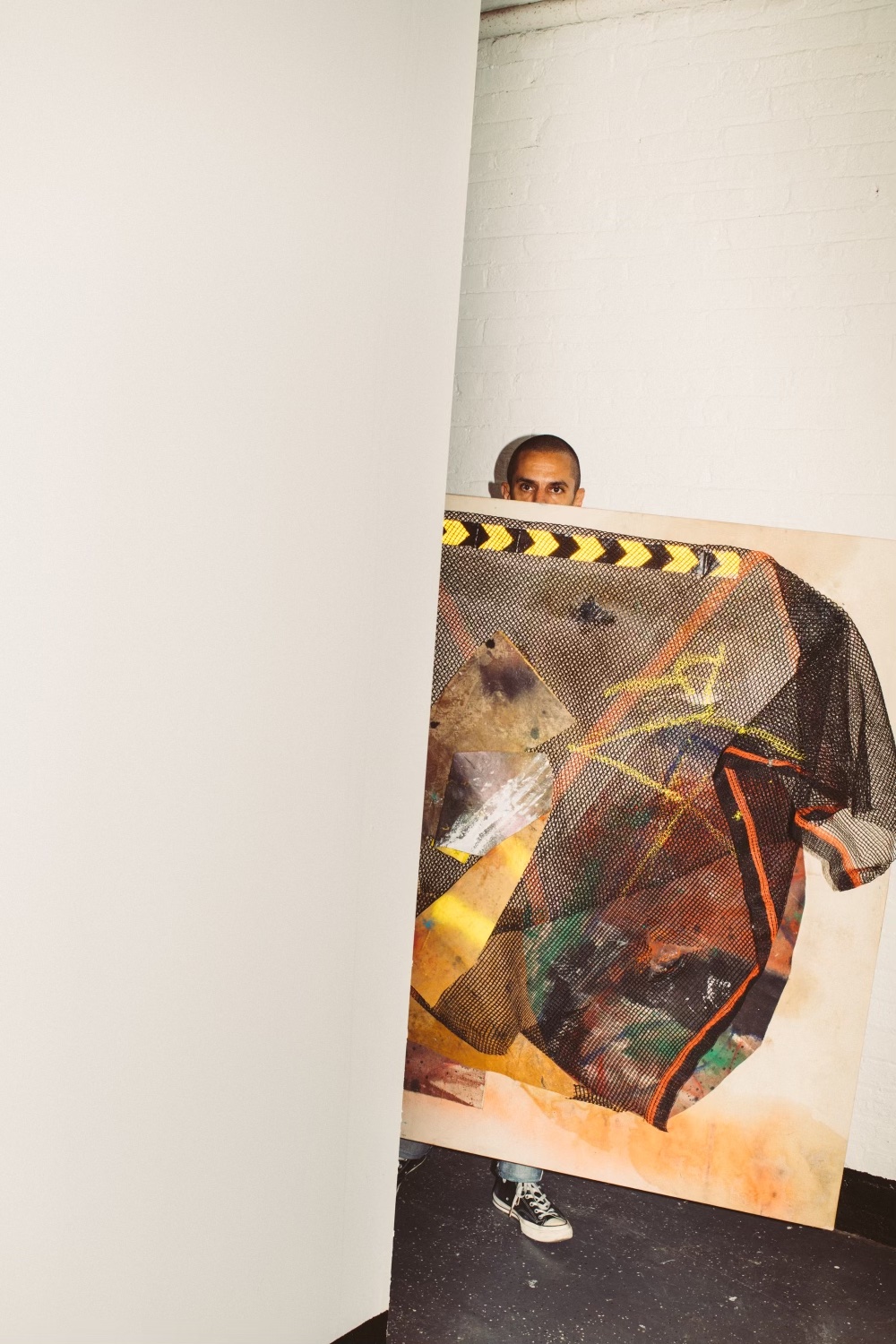

Raised by artist parents who imbued much of his cultural understanding during his upbringing, Salomão traversed childhood with an insatiable thirst for knowledge and an innate curiosity. "What I gained from my parents was very precious. My mom and my dad were kind of these encyclopedias of culture," reflects the New York-based artist.

Growing up amidst Brazil's Tropicália movement, a creative and musical revolution that was born from Bossa Nova and the oppressive regime of the time, Salomão was exposed to a golden era of music that sparked a profound awakening within him. While his parents were spiritual seekers, it was music that served as his initial gateway to the spiritual realm, a connection that still resonates deeply in his life today. "My first connection with the spirit world was actually playing Jimi Hendrix’s music," he explains. "During that journey, I realized there’s something else besides this reality. We can also paint our reality from the inside out. I didn't even know how to really play [guitar], but I was in a trance. I connected with the music, and I was in a trance with this spiritual world."

Drawing inspiration from the music of the 1960s and 1970s, delving into the writings of Carlos Castaneda, and immersing himself in Afro-Brazilian Yoruba, Buddhism, and Tarot, Salomão's spiritual immersion in Brazil was just the beginning, laying the groundwork for how he would navigate life and express himself creatively.

Arriving in New York in the 90s, 15-year-old Salomão found himself in the underground punk scene of the Lower East Side, skateboarding and playing in bands while absorbing all the cultures that inhabited the neighborhood. “I feel like New York was such a poetic place back then, where it was raw, the Lower East Side, the village was so raw” Salomão recounts.

Navigating the concrete jungle, the multidisciplinary artist discovered graffiti as a means of self-expression beyond his musical pursuits. "I had this urge to express myself, and it came through graffiti. I started to paint this name, this rebel name called ‘PIXOTE.’ It became a mantra. It was very much about me finding myself and my individuality," Salomão explains. "Putting up your name, you become a part of this landscape, this urban landscape. This opened the door to the visual arts, where I feel like all art forms are interconnected."

Since venturing into visual art, Salomão has continuously pushed the boundaries of his craft, refusing to conform to the constraints of medium or categorization. "I'm more of a visual poet or a multimedia artist. I don't particularly say I'm a painter. Even when I paint, I feel like an alchemist because I'm dealing with energy. And, that's how I see paintings or art being a tool of healing. A tool of actually bringing people outside of this normal reality, and to embrace this mythical world."

For Salomão’s latest offering for his solo show “CIRCO DE VISÕES," paintings, works on paper, and sculptures act as vessels for abstractions of daily life. Creating an assemblage of found objects from scrap metal to Salomão’s father's journal entries, creative brevity ties the work together. “There is a notion of freedom in each artwork that I do, almost like a tarot card. I embrace this freedom. I don't have a form of how I'm gonna make actions, but I have this little connection with the work, which it's kind of a spiritual dialogue with each work” the intentional artist expresses while the sun illuminates his silhouette. “I let the paint lead the way. I prime the canvas, and then a lot of times, I leave some coffee stain, oil stain, or linseed oil, letting the stain lead the way of how I want to build this art form.”

The compositions of Salomão’s paintings are an amalgamation of sourced materials, graffiti, and oil paint, accentuated by Japanese caligraphy-inspired brushstrokes and a palpable sense of urgency. “A lot of my work has these collages of patches, fabric that I've been collecting, or that I maybe already painted. And I think they have a life of their own own and own knowledge” he observes. “I also brought in elements of a construction site, little things that I saw on the street that I love in terms of the mask that they used in construction, and I like this urban fascination for imperfection.”

While painting allows Salomão to articulate the thickness of his mind, works on paper oftentimes are an easier form of expression. “My art is completed by the viewer. I give a lot of gaps for the imagination, for one's perspective” he expresses. Inspired by his father’s poetry and ephemera that was recently passed down to Salomão, “CIRCO DE VISÕES," came to be through “this unconscious world of symbols, archetypes, and title cards” in his words. “My father being a poet, and leaving me so many artifacts, little journeys, and poems, I was looking for a name–and it came to me.”

Anchoring the show is a new arrival for Salomão, where he is presenting a sculptural homage to Marcel Duchamp’s 1913 Bicycle Wheel. Tied to the spirituality of Dadaism and Duchamp’s artistic objectives, Salomão's art merges his external and internal worlds, unified by the spirituality that connects them.

As you step back and observe the dialogue within each of Salomão’s artworks, a collective exhale takes place. In a world constantly in pain, with futures appearing increasingly bleak, Salomão’s art serves as a reminder that accessing a higher consciousness through art, music, and meditation can foster a stronger, more connected sense of being with the world around us. He states, "I realized very early on that spirituality is something for us to connect to within our lives. Often, we are so consumed with our outer world and everything happening there that we forget our inner world and the importance of tapping into that."

“CIRCO DE VISÕES” is on view at Gallery 495, Catskills, New York, running through July 27.

We can look at any one of Isaac’s pieces and understand almost immediately what it's about, or at least what we think it’s about. But that’s the beauty of Isaac’s work: no matter the subject matter, we see ourselves, or a friend, or someone we love in all of them. At just 21 years old, he has created a body of work reflective of the universal moments that connect us all.

Read our conversation about Isaac’s process and purpose as an artist below.

I feel like we’ve been in communication on and off since the days of the pandemic. Visually, I’ve seen your work change so much from four years ago to today. Do you feel like there was a switch in your life that resulted in this change?

Yes, for sure. I went to see this Jennifer Packer show at Serpentine in around 2021,and at the time I was doing quite abstract paintings – aesthetically they were pretty but they weren’t really saying much. I went to that show, and it made me fall in love with painting people. The way she paints people, it makes you feel this really deep connection. I thought it was really fascinating, and so I decided I wanted to start painting people. Before this change, my work was much more self-referential. I did self portraits, about mental health, and I used myself as the subject of my work. But around the start of 2023, I lost my very close friend, and that’s when my work really shifted towards this theme of human connection. So now, my work is about relationships, and moments of intimacy and human connection.

That’s super interesting. I see the conceptual shifts, and change in emotional approach to your work, but I also see a huge shift in the techniques you are using — all these lines that you create through negative space, and the vibrant use of color. Where did that come from?

Well, back when I was painting self-portraits, I wasn’t particularly good at drawing, so I was always drawing these very loose silhouettes with line work, and I liked it a lot but the colors weren’t quite right. I literally had to teach myself how to paint with oil — I was learning through YouTube — and one of the things it taught me was this process of doing a wash to stain your canvas. Most people paint over that wash, but I really liked that color and the tone it gives the whole canvas — it’s almost like a sepia photograph that feels really nostalgic. So I kept that color visible through the line work which massively changed the color palette of all my paintings. And not just the color of this process shows, but also the texture. Painting the canvas with this burnt umber and white mix, then washing it down with this very toxic turpentine creates this almost wood-like texture, making my paintings look like they’re printed on a wood block.

So you’re kind of allowing the process of the medium to show itself in the final piece.

Yeah, I just thought, it’s such a nice color, why get rid of it? And also, this color became the color for all the skintones in my pieces. With my current style, that is intentionally very 2D and very flat, the sepia wash and the line work replaces any shading, on faces or on things like draped clothes. In my paintings, I want there to be no evident light source, and the intention behind that is that my paintings are slightly disconnected from the real world, they aren’t real life. The figures aren’t real, none of them are real people. They are everyman type figures, so they can be universally understood. By doing this, you can understand what the human emotions of the painting are, while not assigning these emotions to specific people.

I think this sense of ambiguity you’ve created in the figures is super effective. As the audience, we can apply ourselves to the work completely. It’s like reading a book where the character traits of the protagonist are left quite open, and you can put yourself in their shoes.

That’s exactly the intention. There’s no context to the pieces, no branded clothes, no specific time, or specific place. And that's what I love so much about the ambiguity, how I’ve had people come up to me at shows and say, “This painting is my grandad, this painting is my wife, this is my daughter, etc.” People are able to take what they need and what they see from my paintings. I always say that I have a story to tell, but it's not the story, it's just a story. And because my work concerns the human experience, and all these human emotions, you don’t always know the story but you can always understand how it feels. When art is too prescriptive, it loses its magic.

Your work is evidently expressive, and stemming from the self but you’ve also done some commercial work in your career. Do you feel that there is a disconnect in creating fine art for commercial purposes?

Definitely, the intentions behind the two are very different. I’ve kind of turned down quite a bit of commercial work for that reason, partly time — if I’m painting, I want it to be something I want to paint. But on the other hand, there has been commercial work that I’ve enjoyed, like painting guests at an event for Miu Miu, where I got to practice painting in a completely different environment and timeframe.

Now you’ve done these super cool collabs with some major brands, but rewinding to your beginnings as a younger, less established artist, do you feel that there is enough support for aspiring creatives in the industry?

No, there’s literally no support. At the time, I remember thinking “Why isn’t anyone helping me out?” but in hindsight, it actually forced me to do things like throw my first exhibition at fifteen. And for bigger opportunities, and working with brands, I’m so glad those things are happening now instead of back then because I wouldn’t have been as ready back then – it forced me to realize that the work wasn’t there quite yet so I had to keep working and improving. I feel like I’m still very much in that phase of trying to get better and better and better, to put myself in the best position possible.

Experiencing how there aren’t many spaces for aspiring artists to showcase their work, inspired me to put together things like group shows. In 2021, I was working with Converse at the time, and pitched them the idea of an artist group show. They were down, so we were able to give fifteen artists the space to showcase their work. It gave a lot of these less established artists the opportunity to show their work in a more professional setting, and larger platform. And we did another one again about two months ago. I want to keep doing these things for sure, it’s building communities around art.

It's great that you’re creating creative spaces that didn’t exist for you when you were starting. I’m also curious to know, with time and practice of your art, has your creative process evolved?

Yes, definitely. I plan my pieces a lot more now. Especially for these larger ones, I plan them quite meticulously. A lot of the time, artists say that they won’t know what their end product will look like, but for me, I pretty much always know what my paintings are going to look like. The colors might change, but compositionally I know where everything is. And this is mostly because of my process with the line work — it being the very first layer I work with. Once I add the color blocking on, I can’t go back and add the lines back on top of it because it has to sit on the original layer of the canvas. I guess my paintings are kind of like coloring inside the lines. A lot of artists can let their painting process guide them to the final product, but I find that I need to be quite aware of my planning and end goal.

Nowadays, I also work on pieces simultaneously and it helps me build a cohesive body of work. For example, I’ll be working on a piece with a certain color, and then I’ll go and apply that same color to another piece that I’ve started. The look of one piece will end up influencing the other pieces around it.

That’s interesting, do you also feel that working on one painting sparks inspiration for the concept or subject matter of another painting?

Definitely, yes. For example, this piece I’m working on right now for Tate Modern, it’s influenced by another piece at the gallery, but one of the reasons I chose that piece is because it visually connects to my flower series paintings, so kind of referencing the other pieces I have worked on. Often, I’ll paint a certain subject matter, such as Mother and Daughter, and will continue that subject matter in multiple of my pieces.

Speaking of your flower series, it really stands out to me because I noticed that while all your color blocking is flat, you’ve visually separated the flowers by painting them in gradients.

Yes, so the first of the flower series was a painting of just someone’s hands and then flowers, taking up the entire canvas. And this start of the series stemmed from an interest in looking at the psychology of relationships and gift giving. Specifically, how the gifting of flowers can actually mean so many things, like a romantic gift, or a celebratory thing, or a sympathy thing. So yes, I wanted to focus on the symbolism of flowers in human relationships and decided to give them some shading and gradient in order to give them a bit more life, while still not separating them too much from the flatness of my work. Within the composition of human figures, I really want the flowers to be the main focus, for them to stand out as much as possible.

And in these compositions of people, do you work from references?

A majority of the time, these aren’t real people I’m painting. Some compositions have a very loose photo reference of, for example, the form of the body while hugging. But I will say that I’m always taking mental notes of the way someone’s standing or sitting, or watching little altercations, or conversations between people on the tube. Subconsciously, there are scenes I see of the city that help inform my paintings. Especially in a big city like London, there’s always something going on and so these things stick with me and they translate into my work in one way or another.

We’ve talked about your work in the past, and its development to the present. Where do you see it going in the future?

So obviously, to keep painting is the main focus of my practice. But I also want to go into filmmaking, and I’m in the very early stages of working on a short film. I actually used to act when I was younger but realized that I might want to be on the other side of the camera. My paintings right now are sort of like cinema stills, so this short film I’m working on with a friend is based on my paintings. It deals with two sisters losing their mother, and surrounds the relationship of the two through quite a naive and child-like perspective.

I can see that translating beautifully. Your paintings capture scenes of life, and that is exactly the essence of film. Thanks for chatting with us!