Model Behavior

Holly is one of many talented young creatives representing the changing face of London’s design scene and industries alike. With a formal training in architecture, deep experience in front of and behind the camera as a successful set designer and fashion model, and her own design studio — ROLSTUDIO, founded in 2021 — Holly is in the first phase of what will likely be a long and successful career — in many fields and disciplines. Like the designer-model-creative director, many young Londoners are seeking a new kind of creative pathway: a cross-industry career that culls a diverse array of jobs, incomes, and identities, rather than a singular one. And her hard work has gained her some notable accolades: modeling work with clients like Jimmy Choo, Burberry, and Agent Provocateur, plus features in T Magazine, Prada Young Designers, and The Face.

There’s a real power that lies in Holly’s kind of interdisciplinary approach, connected to a strengthened sense of community and the waning of the age-old solitary creative genius archetype. I had the opportunity to spend a week with Holly and her crew this past August during my time in London, and it was exciting to see the breadth of each person’s influence: models/designers, photographers/neuroscientists, stylists/clothing designers; people not only accepting their multifaceted nature, but embracing it.

Working in a creatively dense and expensive city like London comes with its own set of challenges, and Holly isn’t one to shy away from sharing her own experiences. Working as a model in an ever-evolving fashion industry offers a multitude of both pros and cons, while working as a designer is costly and filled with long days, especially when things go awry.

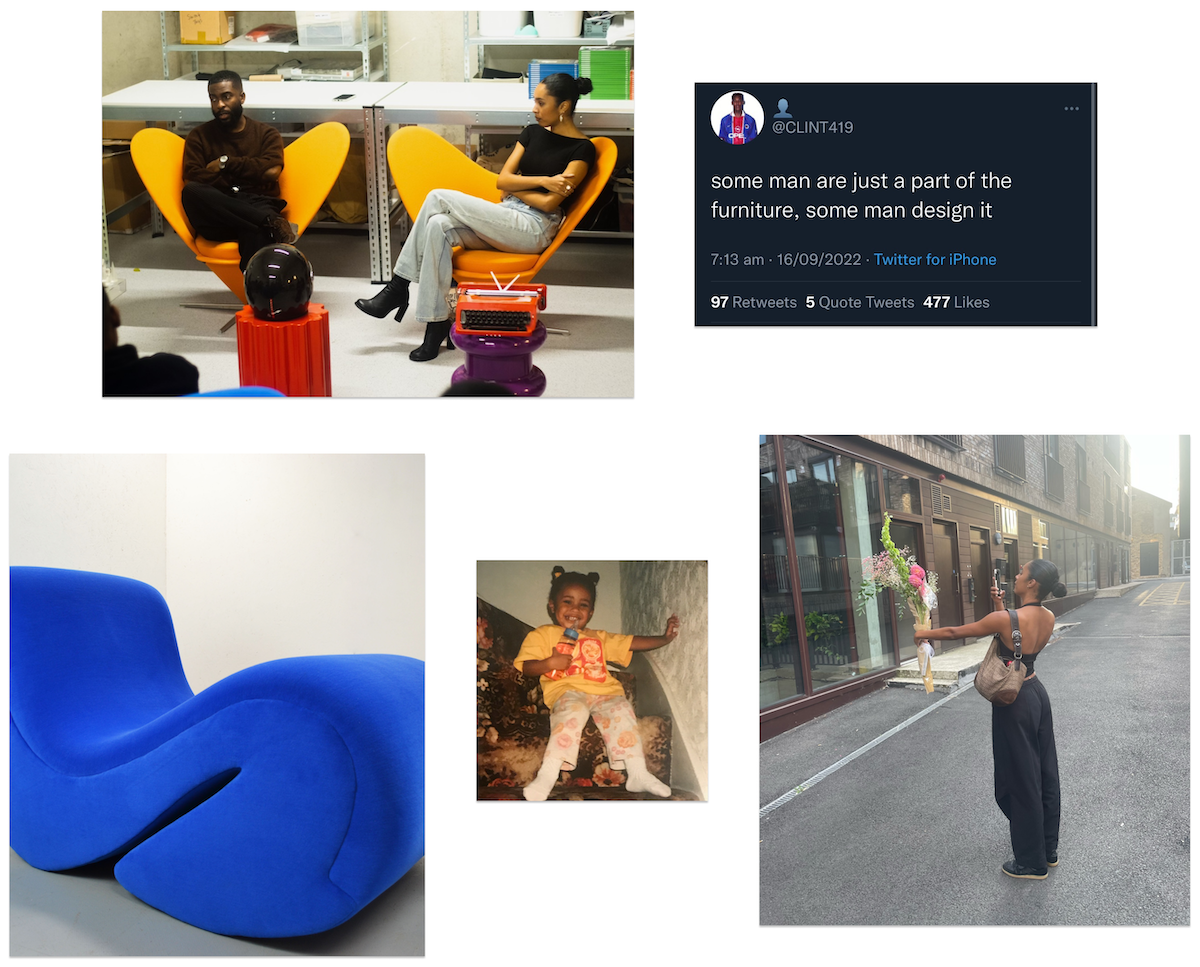

The Aura exhibited as part of Ronan Mckenzie's "To Be Held" exhibition earlier this year at Carl Freedman Gallery.

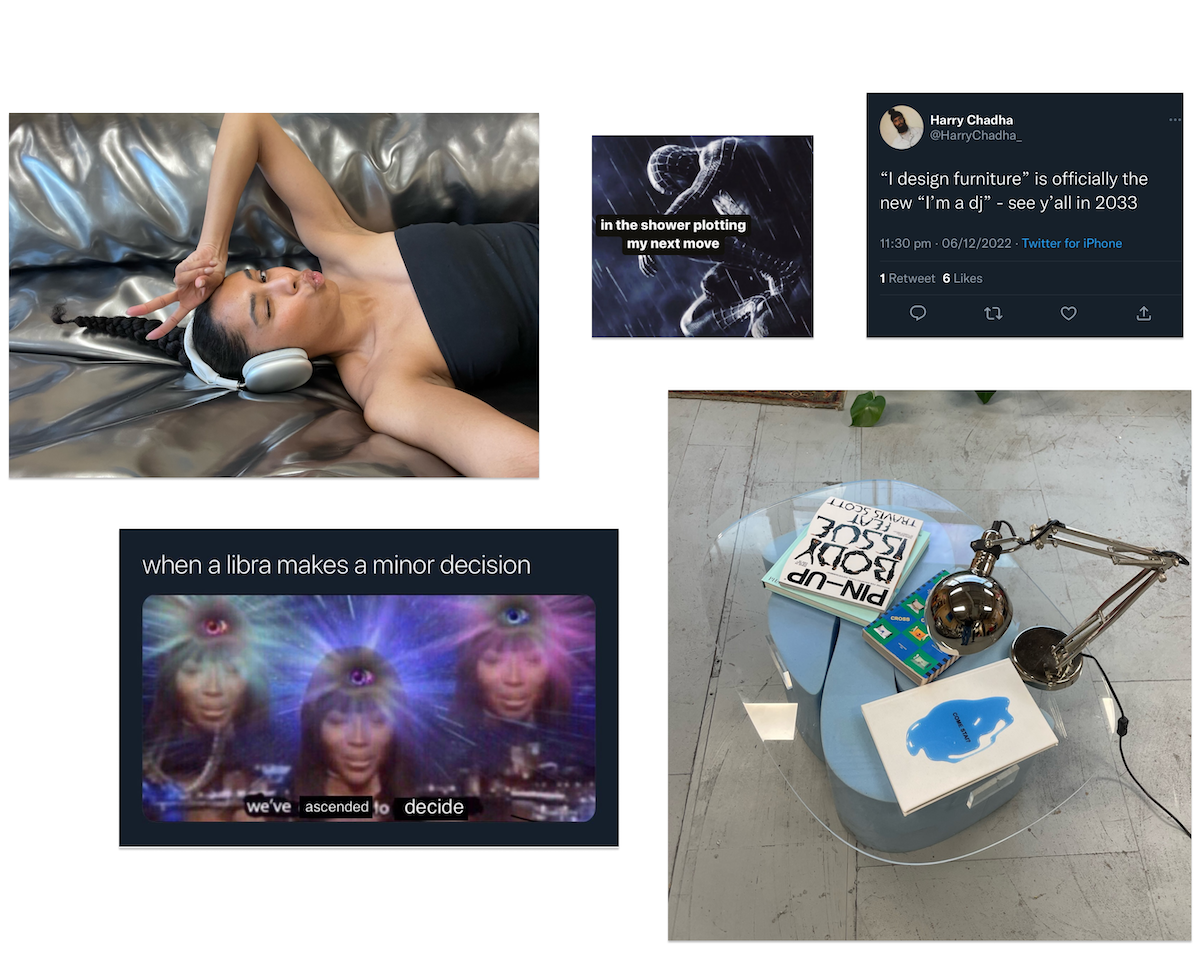

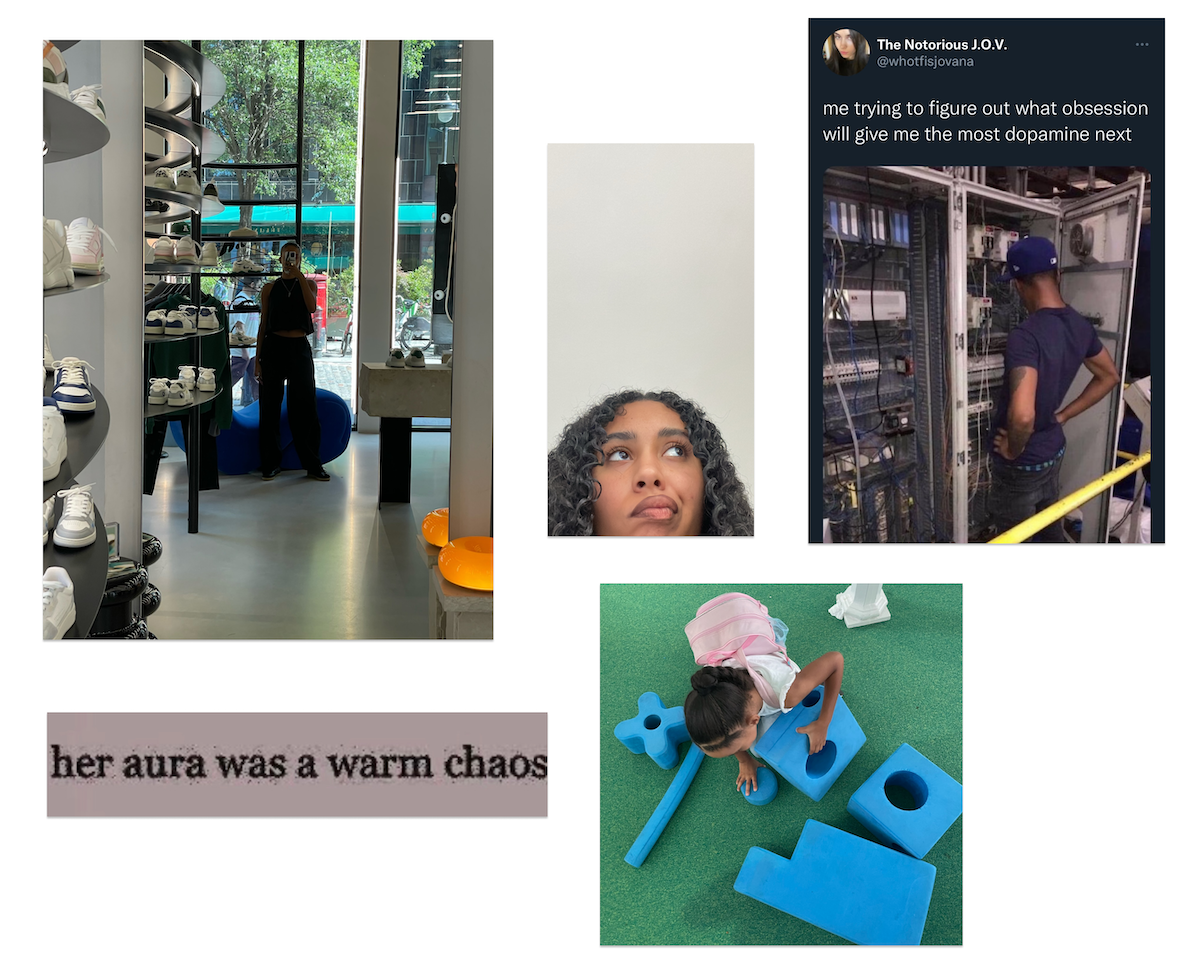

A perfectionist at heart, she speaks about working to be more open in sharing her process — both the highs and the lows. For this interview, I asked Holly to put together some imagery: photos, screenshots, tweets, and more from her voluminous phone archive, wanting to tell her story not just with our conversation but with all of the weird and lovely things that draw her attention day-to-day. For a multihyphenate like herself, days can look very different one to the next: Monday might be a full day of shooting, while Tuesday is taken up with reviewing samples at her production house.

It’s all in a day’s work for Holly — read on to explore her world and our conversation on IKEA, crying on camera, and reaching a creative flow state.

David Eardley— There’s something interesting in your work — this particular balance of comfort and edge. It feels like you value the usability of the piece but aren’t willing to let the comfort overpower the actual presence of the pieces.

Holly Rollins— I think there's a certain juxtaposition that I'm trying to convey. Have you ever heard of Zen brutalism? It’s the concept of something that’s aesthetically cold and not very inviting in its shape and color palette, but that also brings you a sense of peace. I think I'm trying to convey that, in a similar way. Execution-wise, I design differently: my work is more playful, but the colors are more brutal. It sort of emulates the urban environment that I've grown up around. But still softcore and playful and inviting.

Where does that come from? I’m curious about your relationship to London.

I don't think — unless you grow up outside of the city — you don't realize how overstimulating and harsh being in a city is, to your senses constantly. So subconsciously that is programmed inside of you, right? You're reflecting what you see every day and you're taking inspiration from that. So I think the city has really influenced a lot of my design choices subconsciously. Another part of it is my personality, how I view things and what I like to have around me: a lot of organic shapes and lines. That's not something I necessarily had growing up, although I will say in West London, it's greener and a lot more organic. And there's a lot of nature. You could say that plays into my subconscious as well. It’s a balance of influences.

I really appreciate your attention to detail — it’s been cool getting to know you after my brief encounter with the Aura when we were screening pieces for our Wear Your Chair 001 tshirt. Then seeing it on the shirt, and then meeting you, getting to know you, and seeing how that chair connects to your other pieces, like the sofa you’re sitting on now. I enjoy seeing the aesthetic through line because I'm always interested in how expansive or how someone's eye is — in their own work — and what characteristics are carried through in each of their designs.

From what I’ve seen, there’s a sort of icy palette that is a core part of your catalog.

Yeah, it's cool toned, for sure. Kind of frosty. With these recent pieces, I was super intentional … I wanted everything to really coincide, so it looked like a complete collection.

No matter what I produce, it will all always go together. I think naturally I gravitated towards that sort of palette, but in the future I'm going to try and branch out.

I really like it — it's refreshing. Just being online, you’re probably hyper aware of the overpowering presence of all-neutrals in design today. It’s sort of exhausting to me, though the colors aren’t necessarily offensive themselves. It’s just like: “Not another creamy beige …”

It’s seeping into children's toys and nurseries. And it doesn't have to be like that. It's quite frustrating actually, because I feel like if you have something really playful and you put it into those beige tones, it's kind of sucking the playfulness out of it. And then it's just conveying different messages. I think the kids that will have grown up with this beige generation of things might have some warped perception of playtime.

100%, It's actually a weird reason that I love Ikea — seeing the children’s section and how maximalist it is. I have this orange plastic stool that I just love … and it’s from the kid’s section.

Yeah, I have the bright yellow one sitting in the corner.

As someone who looks at a lot of finished design works, I think that it's always important to think about everything that came before a piece — all the iterations before a final product. I like that you and I have had the chance to have these conversations, about the way that when you design for an intended purpose, sometimes your plans don't always work out the way you intended. Things have a life of their own.

I think those conversations are really important to publicize. Seeing all these final products on social media, it can feel so isolating when things go wrong … when you see all this beautiful work on Instagram.

Have you had any sort of lessons or conclusions this year about the unpredictable nature of being a designer?

Yeah, definitely. When I first started out, I was designing less practically. And then once I had a kind of plan of where I was going, I would try to incorporate more practicality into the design, or work out the flaws. And I guess that's what sampling is for. But there's certain things you can't do; you have to work with practicality and “purposelessness” hand-in-hand. So, functionality wasn’t something I always considered — I'll be straight about that.

It's always been about how things looked or what they meant, or the choices behind the materials and the shapes. But when you're designing like that, you run into a roadblock because there's certain things that people either don't want to help you manufacture, because they haven't done it before. They can't see how it's going to look, outside of your renders or your head. You can explain to them as much as you want, but it won't stop them from doubting how it's going to function and how they're going to build it for you, or how you're going to build it yourself.

So it can take a lot of time back and forth to help people see the vision before the actual creation. And I think that's where my road stops — finding people bold enough to want to help you create it. And then once they're creating it, there's these stops in the road — tackling shape and materials.

It's really a labor of love. And it takes months and months and months to develop pieces. I know, on Instagram, you just kind of see the final product and you're like, “Oh, her brain just works like that. And she just made it.” There's so many tears, and long nights and stressful, stressful conversations that you have to go through and tests of materials … that people just don't see.

I think certain people are really good at showing their process — I will say I am not one. I'm a bit of a perfectionist. I’m like, “If it's not perfect, I'm not going to put it out.” But I want to get better at showing the process and making people understand a bit more. I'll get there.

I mean, it's so difficult, especially when you have worked so hard to create something that's so polished. It can be really tough to kind of step back and be like, “Okay, but how do I go against my instinct for perfection and share the vulnerability …”

I’ll be in the moment of creating and be really overwhelmed with the emails and the tests and the conversations and the choices. And I wouldn't ever think like, “Okay, I'm crying in my studio right now because something's gone wrong with my manufacturer. Let me snap a pic and show everybody this is real life.” [laughs]

One thing I’ve come to respect so much about you is your laser focus — you have this deep ability to dive into your work.

I don't know where it comes from, but it's been something I've done for a really long time. I need a lot of solitude as a person, especially when I'm making something. I remember going into my university workshop days: they'd brief us in the morning and then I'd sneak out of class and work in my room by myself or go to the library, because I just couldn't have the external noise.

I think I’ve carried on with that need for a sense of solitude, to create.

I feel the same way. I feel like it’s an example of how systems in traditional education can be tricky, because you're kind of expected to be very tolerant of distraction and still focus.

Yeah, and this constant critique environment — it was so normalized. I mean, I wouldn't say this is a bad thing. But it's normalized to share your work and you know, critique everything, which I think is helpful. But for me, if the idea isn't developed, completely in my brain, and I haven't written about it and completely rolled out what I'm doing, and someone gives me an external opinion on it, it can honestly either throw me super far off course, to the point where I have to get back to where I started. It's weird — I have to execute something to know that I've executed it and then move on to the solution.

I think there are valid concerns people can have, about the one-size-fits-all model of education. When the track is that you have to participate in this same sort of schedule of creative process as other people in your class or your cohort — sometimes that doesn't work for people. I do think that traditional training in design is so deeply valuable; in many ways, this is more just a question about education in general. I've always been a person has had a very difficult time in any kind of traditional educational setting, no matter what I was studying. And because of my ADD, I just have my own kind of process. I do think it’s worth it to investigate the idea of applying one kind of learning model to everyone.

We all learn differently and absorb so differently.

Everyone's brains are so different. And as a person who really came into my creative career and in my 30s, there's always been a lot of pressure, from myself on myself; like, “Oh, my God, but like, everyone's 22 and they're doing so much.” But now that’s turned into using social media and sharing these kinds of stories with people, non-traditional creative stories, seeing others who have a similar experience. Sometimes it just takes longer for some people to cook.

Absolutely. It just takes a while to, but when you find your people, and people you can relate to and feel supported by and uplifted by — that's all … that's all you really need. And it's also just about not comparing your journey. I know that's so cliche — everybody says that — but it really really is. I started my modeling career rather late, in comparison to other models. I was 21. And there are people who started at 14 with developing their books.

But I found other other girls that are my age — you find community and strength and confidence in that. It’s easy to compare yourself, especially in design as well, because everyone has such a different journey into the field. And everyone has different levels of knowledge because of that.

I’m glad you brought up your work as a model, because I think this duality in your work is an experience a lot of people share. A lot of creative people are working two or more jobs, either out of financial necessity or creative necessity. I always want to make this truth transparent, in my journalistic practice. I'm curious to hear about modeling and what it brings to your day-to-day experience — to your work as a designer.

I won't give all the credit to modeling, but I do think it's part of the reason why I am a designer at this age and not later on in my life. I did have an educational background in design, in architecture, and in product and furniture design. And I started my modeling career quite late because I wasn't allowed to model until I'd finished my degree; that was the agreement I had with my parents.

Once I finished my degree, I was like super burnt out from it and kind of lost in the world after university. I knew I didn't want to go straight into the design field — I just wanted to explore the different parts and where I would fit. So, when I started modeling, I was exposed to lots of different job roles: set designers, lighting specialists … things that I knew in my head that I was qualified to do. And modeling gave me a door in — to seeing this — so I feel like it was never just modeling by itself. It was always modeling/set designing, modeling/staging or, you know, art direction.

And by chance I met another furniture designer, Kusheda Mensah, from London, one day on the way back from work with a set designer I was assisting. We got into a conversation and I said, “You know, it’s something I've always been really interested in, I just didn't know you could have a career in it by itself.” And she was like, “Well, why don't you assist me and see how you like it?” And that's where my furniture journey kind of began. I don't know if I would have ever gotten into furniture and being a designer, for myself, if I hadn't seen that representation. And that door opened to me through modeling and the network it brought me into. Everything felt really serendipitous.

But at times, modeling, I’m just sort of judging myself. Like, “Oh, I don't want people to think I got here by using my ‘womanly charm’ or something.” But now I feel like, “This is how I came here. In the grand scheme of things” It's allowed me entry into a world that I probably wouldn't have known had I not been in the career that I'm in. And it's allowed me to get some really great connections and to learn to be a people person and be able to talk to people. My job is never the same every day, I'm always with a different team, a different photographer, and stylist. I've noticed that everybody in the creative field has one or more projects they're working on, and it's normal to discuss them. And then you can kind of start a network of people that you know, and yeah, your skills and experience are expanding every day. So I'm very, very thankful for it.

To me, that is actually the power of being a person with a range of experiences. You're not just in this bubble of the design community — you’re out there in another world and learning from that world. It’s given you these tools to come back and make me a better designer.

What excites you, looking at London and the larger design world and more?

Everyone is multifaceted now. So you can be a designer, you can make visuals, you can make furniture, you can make rugs, you can design fashion — all under one hat or name, with credibility. Being hyphenated and multifaceted is something that's accessible and amazing. And I think that's what's really exciting to me — to see the people that are doing it all. That’s what's really gonna come up.