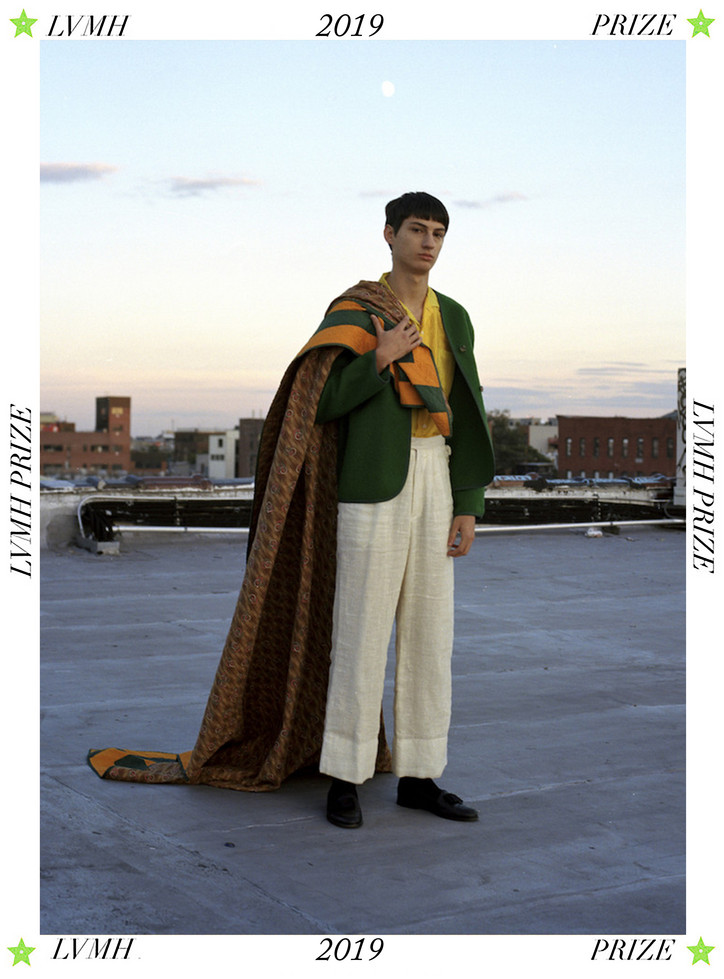

LVMH Prize Finalist - Bode

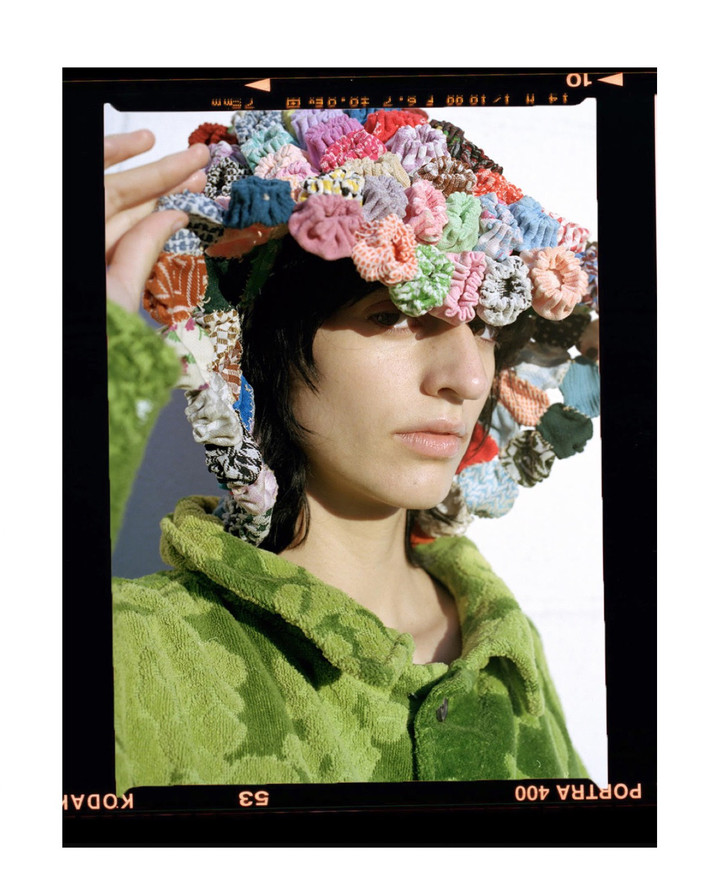

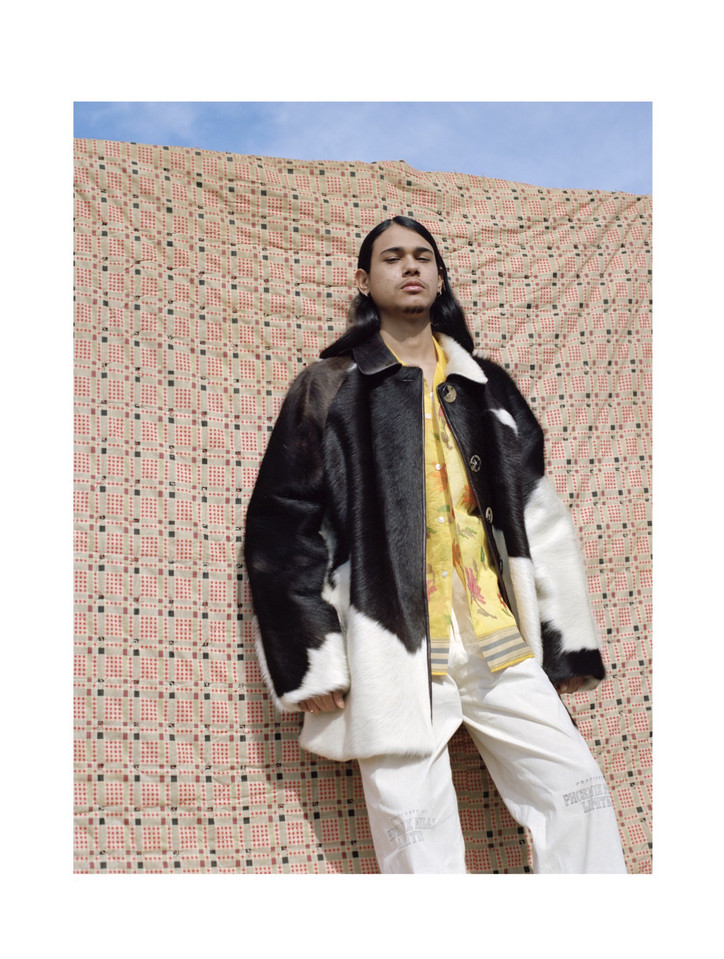

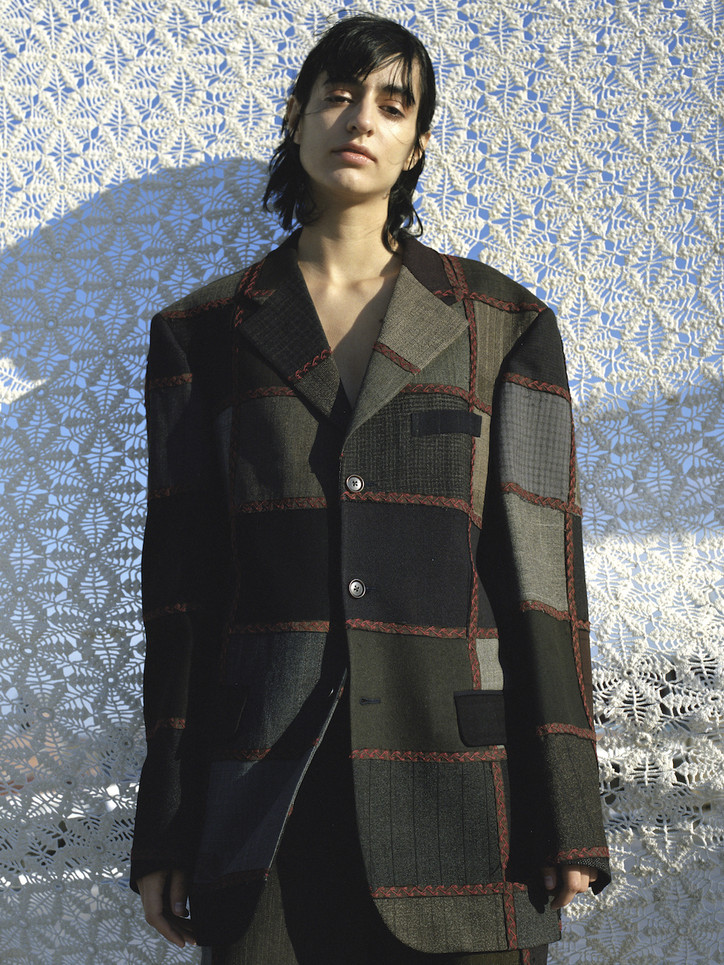

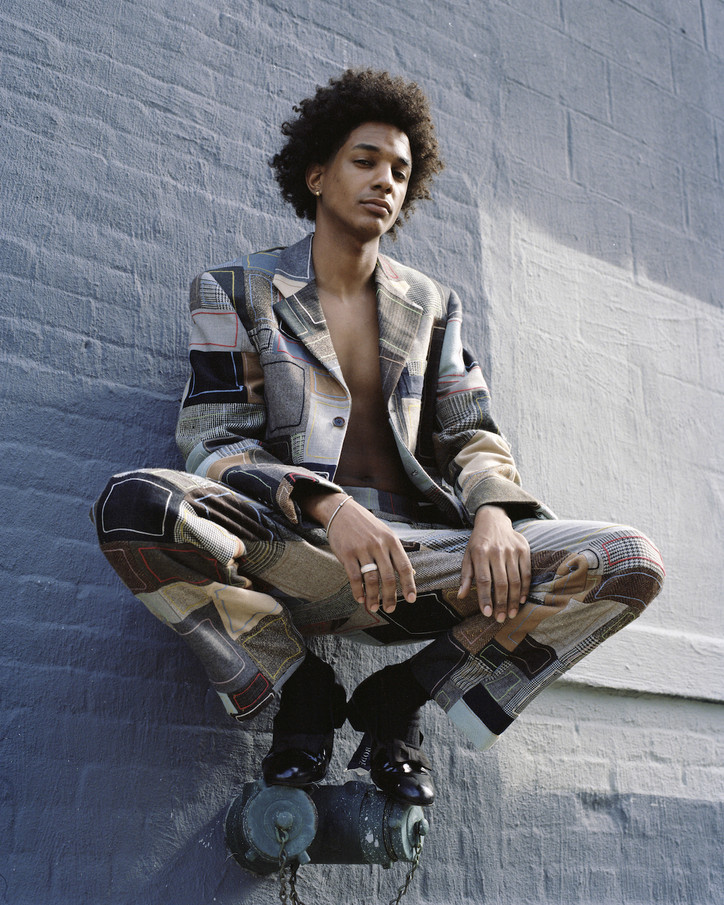

Brands crave a saleable story, a recognizable customer—a tanned woman in the South of France, the phantom skater with disposable income. But Bode’s work comes with a built-in legacy. The designer sources antique textiles, and may be best known for her patchwork jackets and love of quilting (she plans to build out a private manufacturing space with the CVFF prize money). The result is clothing you could see on a consumption-ridden Victorian child that still seems easy to wear; beautifully constructed garments that feel like they will actually last forever, prized heirlooms in the making.

We spoke with the designer about success, antique dolls and repurposing the precious.

You founded Bode in 2016. This is annoying to ask, but did you expect it to take off so quickly? It’s been so successful, so fast.

I don't know. I feel like people ask me that question and in a way, I wouldn't have started a brand if I didn't think it would work. I feel like it was definitely a surprise, but I always knew that I wanted to have my own brand and my own company since I was little. So, it just made sense to me to do it in this way. But I think who's shopping with me and in what way, and I think that was really surprising to me. I don't think that I would have said that I was going to be a business that has their own e-commerce. I feel like sometimes you look at a young designer or luxury price point brands and people don't really sell online, but I think I pictured myself having a store, which is definitely a next step. But I probably didn't realize the way that my business was going to unfold.

Your brand is rooted in tradition, like quilting. What sparked your interest in vintage textiles?

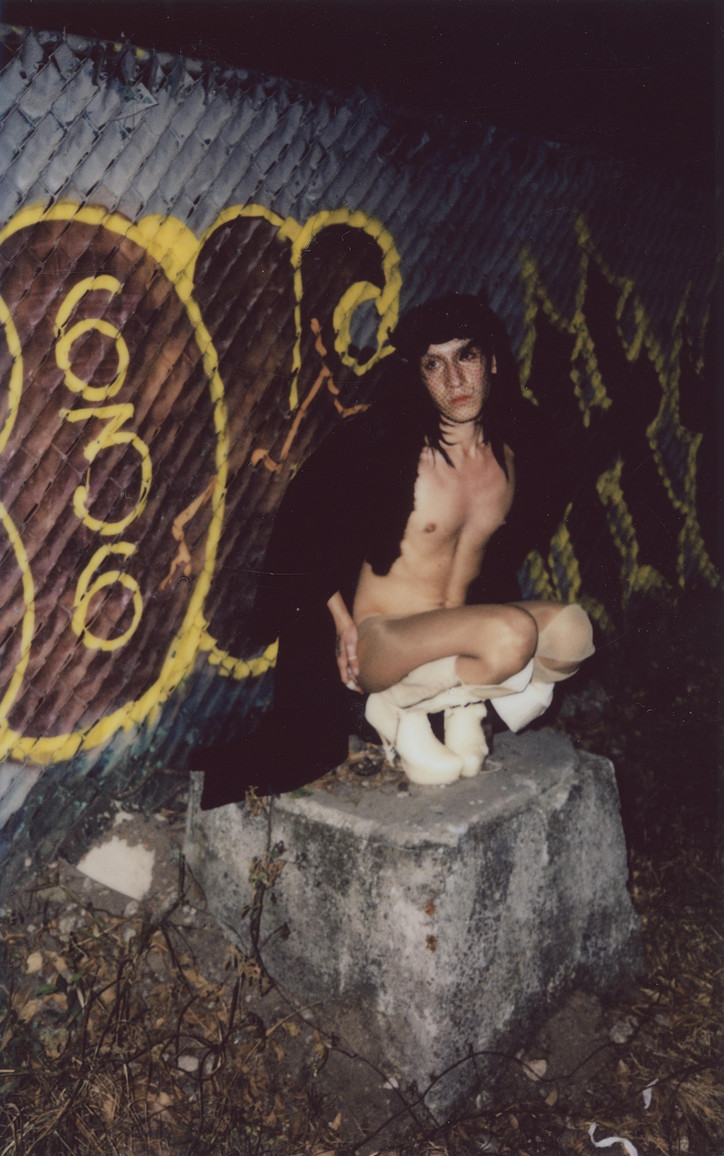

I grew up antiquing with my family, so my mother's father was an antique collector. He was really interested in American antiques and my mother and all of her sisters, so all of my aunts are big into collecting. It's just kind of the way that we grew up. We went to flea markets and antique stores and big antique fairs and auctions. I grew up around them and even as a little kid, I gravitated toward antique toys. So, I had a doll from the 1800s and a little grocery store from the ‘20s. That's what I loved, the past histories of objects, and that somebody made something with an intent and a purpose, and there was this history that had to go along with it. I think that's where my work came from.

There was a great profile of you that mentioned some controversy with the quilting community. Is that still something you experience?

No, it was actually just two main women. But, no, but we're actually very supported in the quilting community. That was probably an old one, I'm not sure. There was a blog post one, but, for the most part—

There's nothing.

Yeah. I've had some of the most important, well-known quilt dealers come to my studio, historians. We have a lot of support from the quilting community. I think it's also knowing what to cut and when to repurpose something, and also when to keep something for domestic use, and when to be able to use it for craft making.

We do a lot of private client commissions. And if a customer says, ‘Here's my great-grandmother's lace,’ I'm like, ‘Oh, I'm not going to be the one to cut that.’ You have to realize that if something is signed or dated or it's really in pristine condition, or if there's a rarity about it and the history or significance of the quilt pattern used, then you physically wouldn't cut something like that.

When do you feel it’s appropriate to cut or restructure something?

What I do love is working on commission projects where someone will say ‘I have this lace,’ or ‘I have these handkerchiefs that I've had in my family for a 150 years, and it just sits in a trunk. My kids don't want it, and we have to downsize the house.’ And that's what I like—for someone to be able to love and reuse an object. They're not gonna put lace on their bed. They're not gonna put a quilt with a huge stain in the middle and bring it to get repaired. There's no interest in that. So, to repurpose those kinds of domestic textiles that have a strong family history is the goal for me—that's the foundation of the brand.

We did a really wonderful project for this woman who we met through other mutual friends. This woman was actually terminally ill, and she wanted to give her grandchildren something—she wanted to pass something on. So, I made shirts for all of the grandchildren out of all of her handkerchiefs. Because we make handkerchief shirts for men.

People don't really use hankies anymore, but they're all so—there's so much work that's involved in handkerchiefs. The embroidery and the lace and all of that was done by hand by her family, so it was a really beautiful way for her to give her heirlooms away, but without giving a five-year-old a handkerchief. She fully understood the way that we make clothes and what our goals are as a business, and being in this culture of giving and sharing personal histories and oral histories.

The way you describe repurposing clothing and giving it a story is really lovely. You’ve spoken about this in the past, but now—especially considering the wide range of CVFF coverage using the word—how do you feel about using ‘sustainability’ as a descriptor?

We don't outwardly say that we're sustainable. To me, it's just an important aspect of our brand that we're sustainable. I think we'll always be sustainable as we scale. It's really important to me to work with individuals who are informed about sustainability, especially as you scale with factories and overseas. We do a lot of manufacturing in India and so what a sustainable brand should look at in terms of fabrics that they use, or dyes that they use, or production practices, that's always definitely at the top of our list. But I don't publicize that we're a sustainable brand. To me, it's just something that I feel very strongly about.

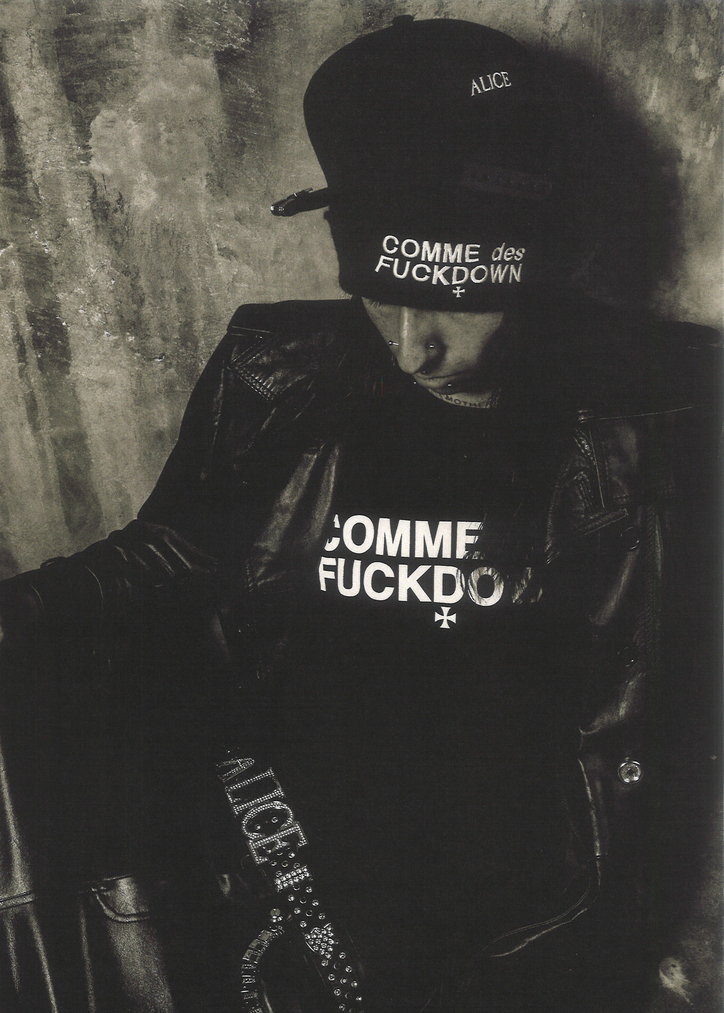

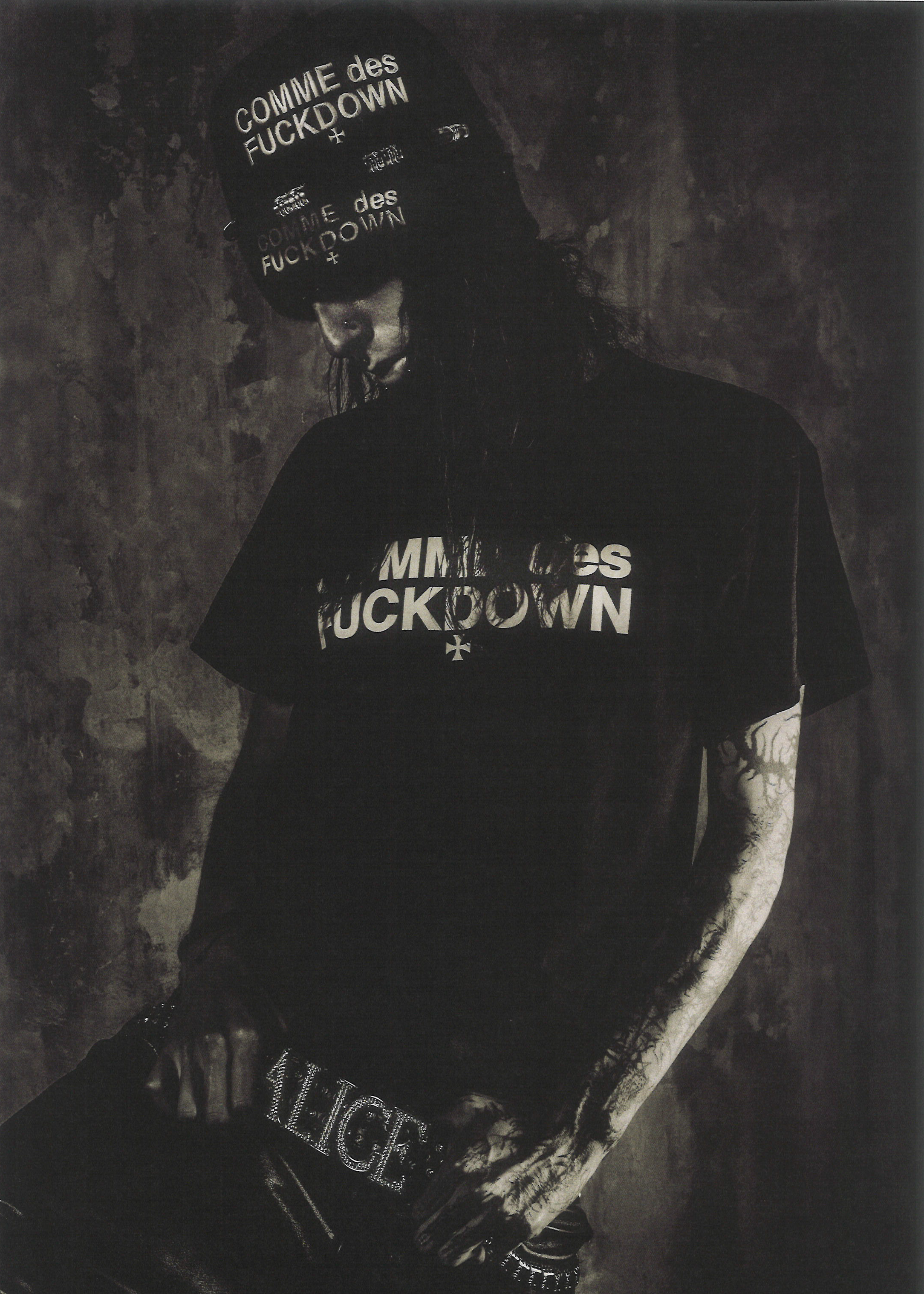

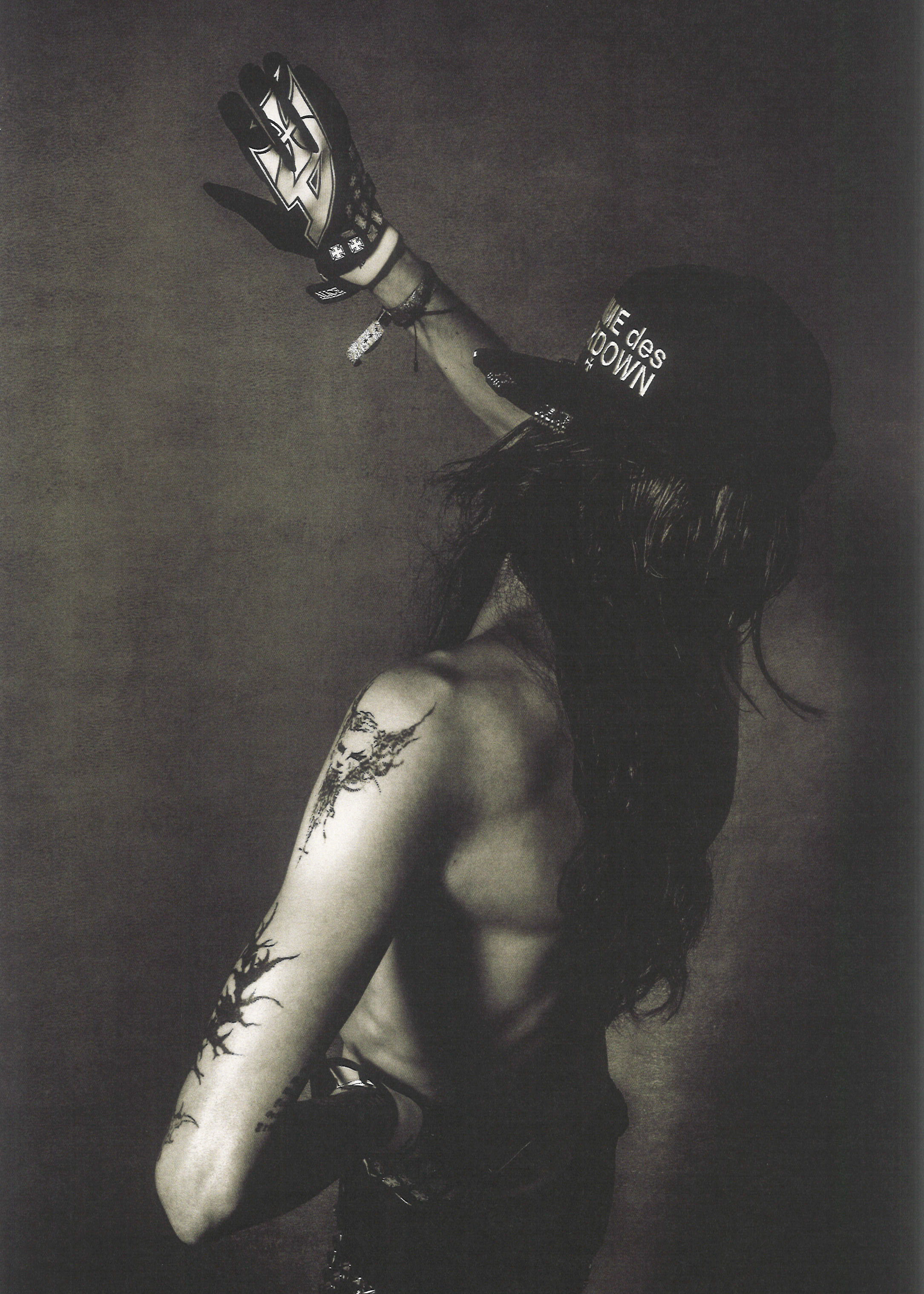

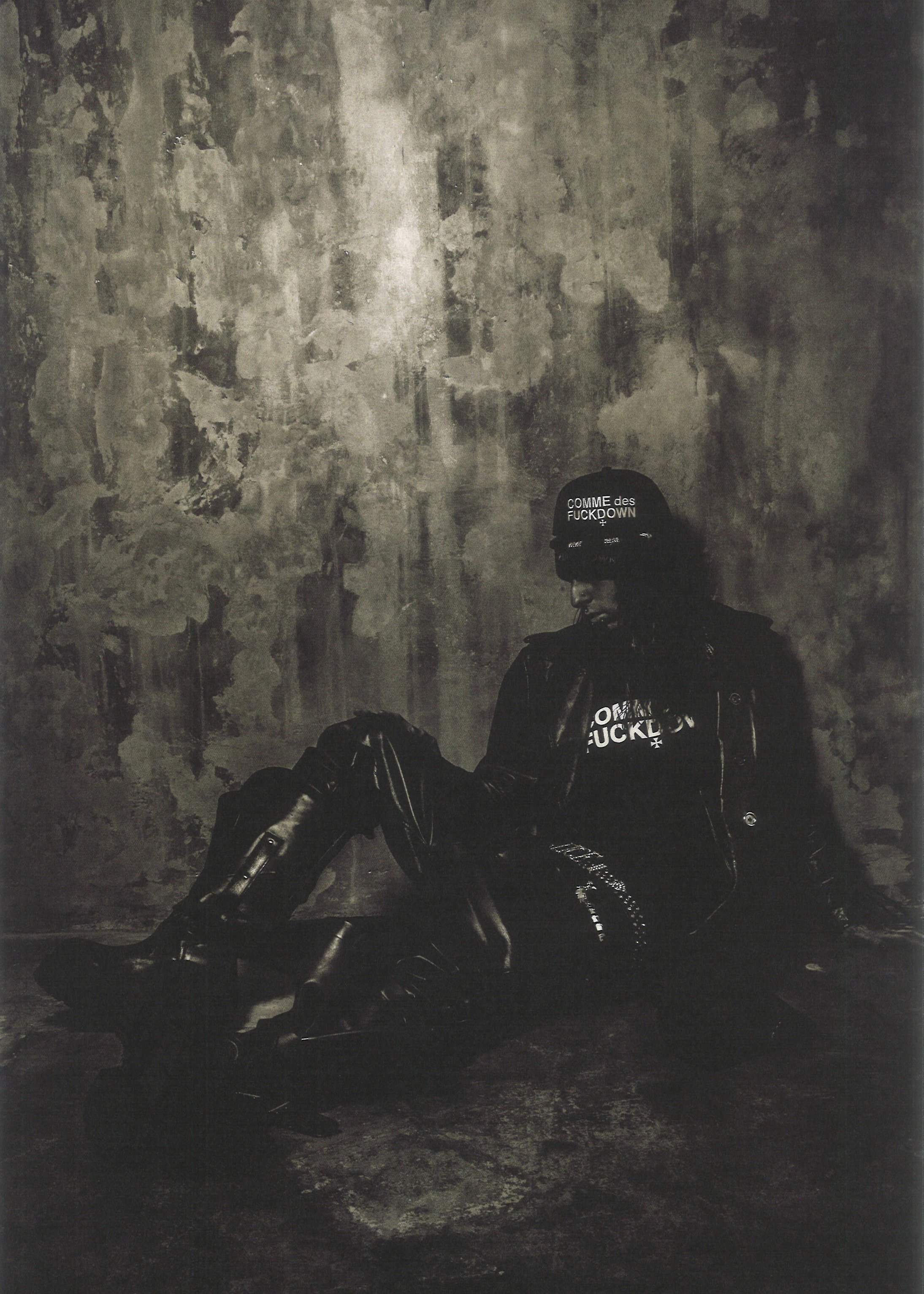

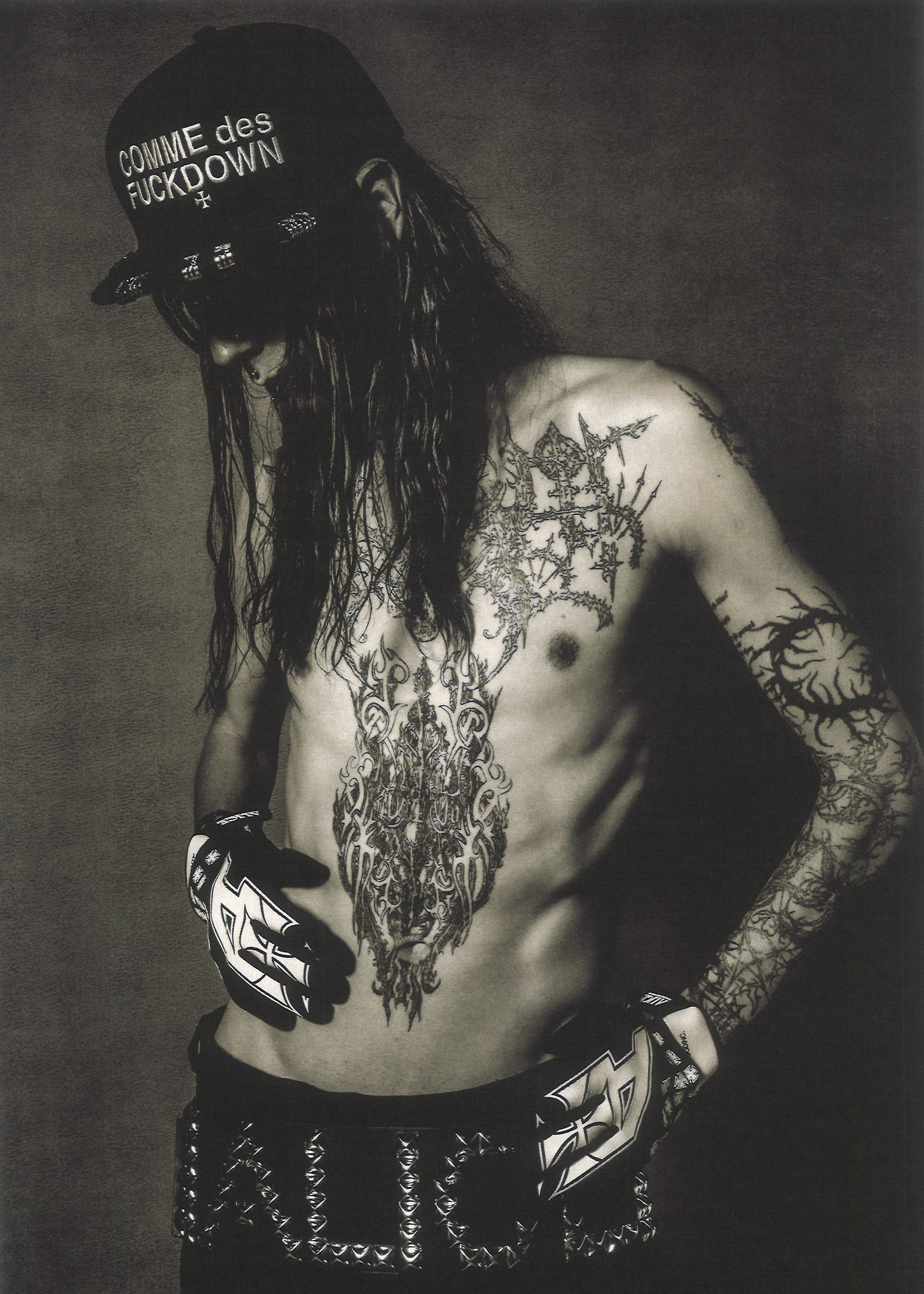

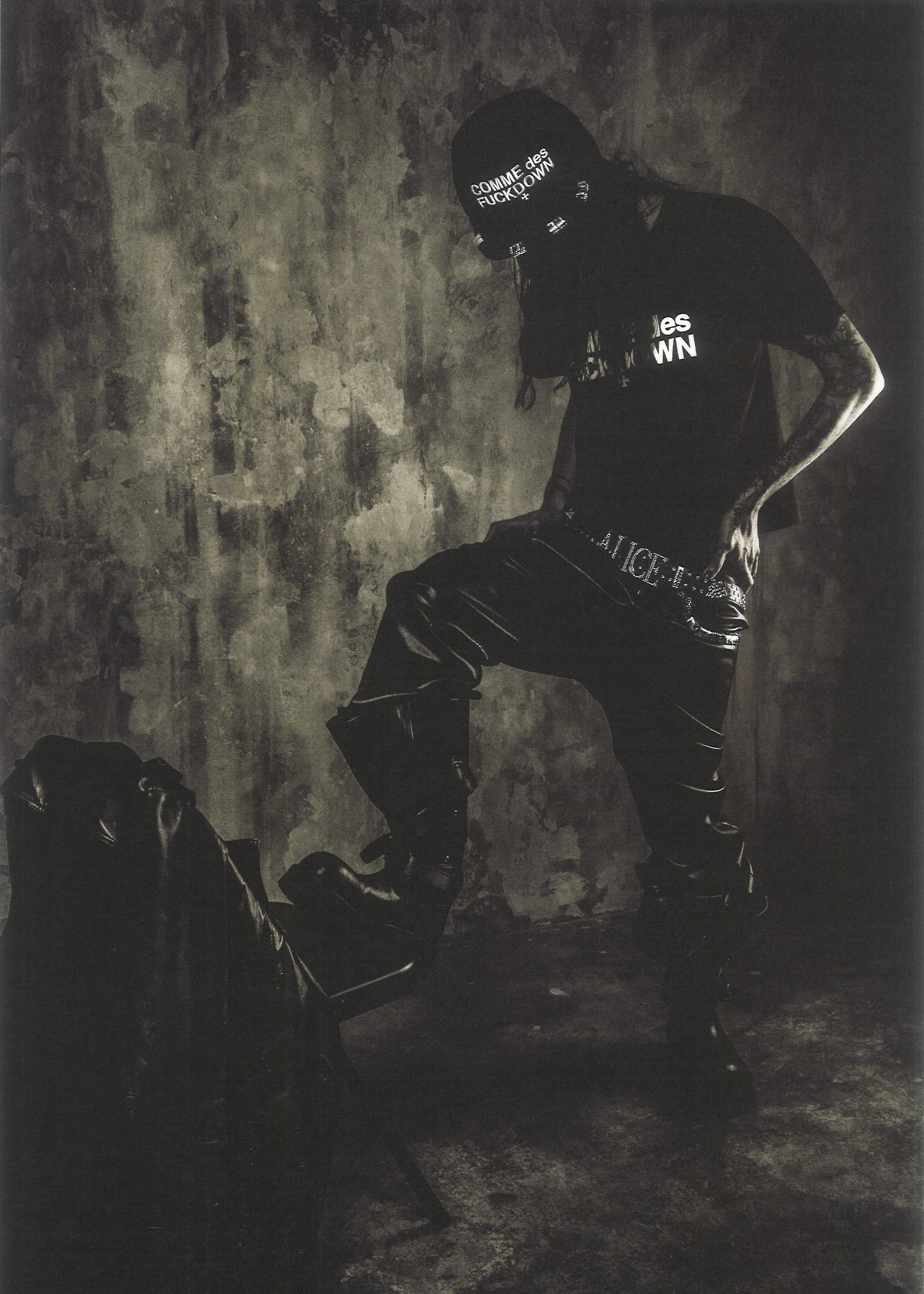

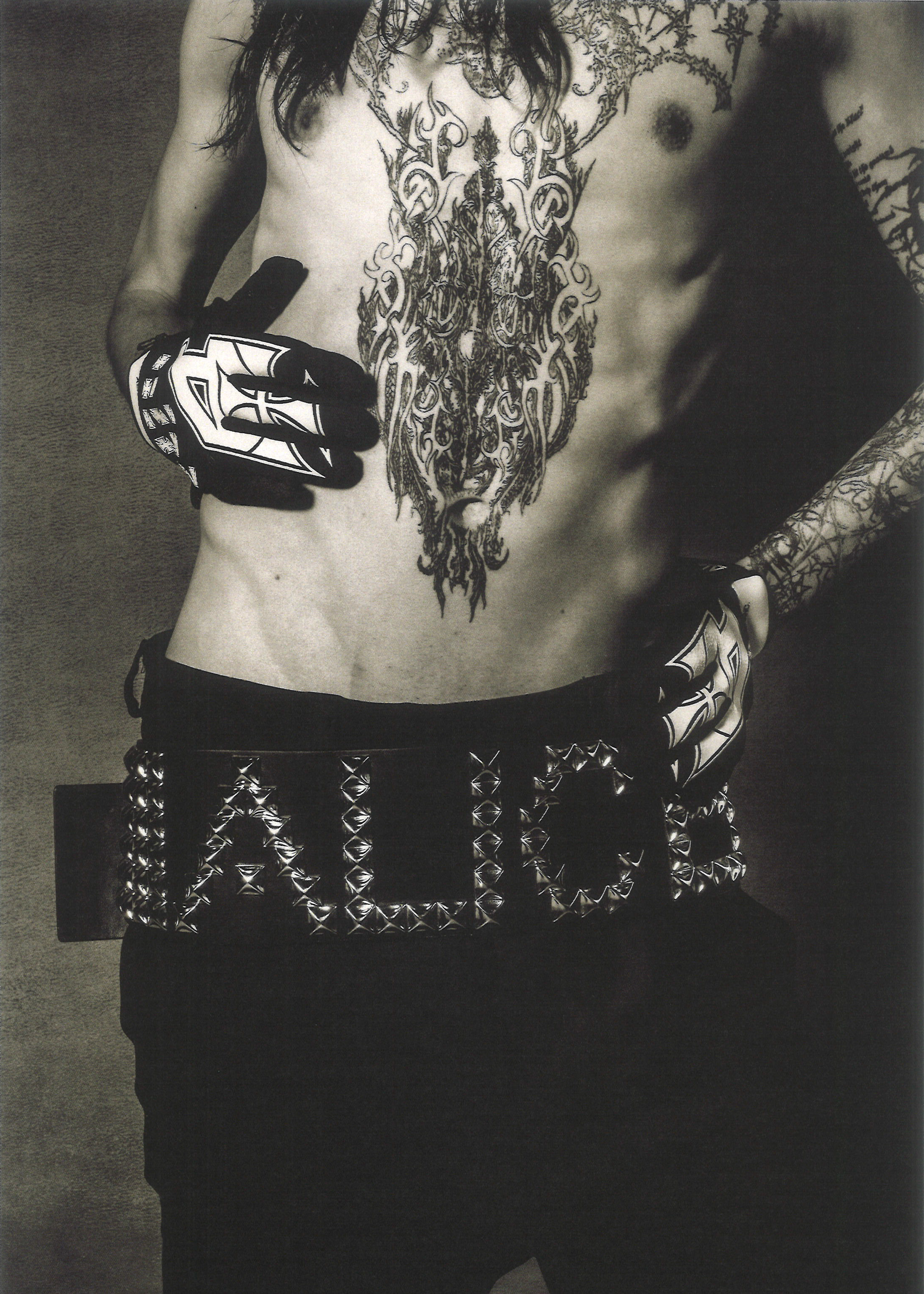

Models: Freddie, Ibukun @ D1, Roman @ Akrav, Jan @ Midland, Chad @ Midland, David @ Midland, Lou @ D1, Zach @ One Management, Diego @ St Claire; Styling Assistant: Samantha Wahl.