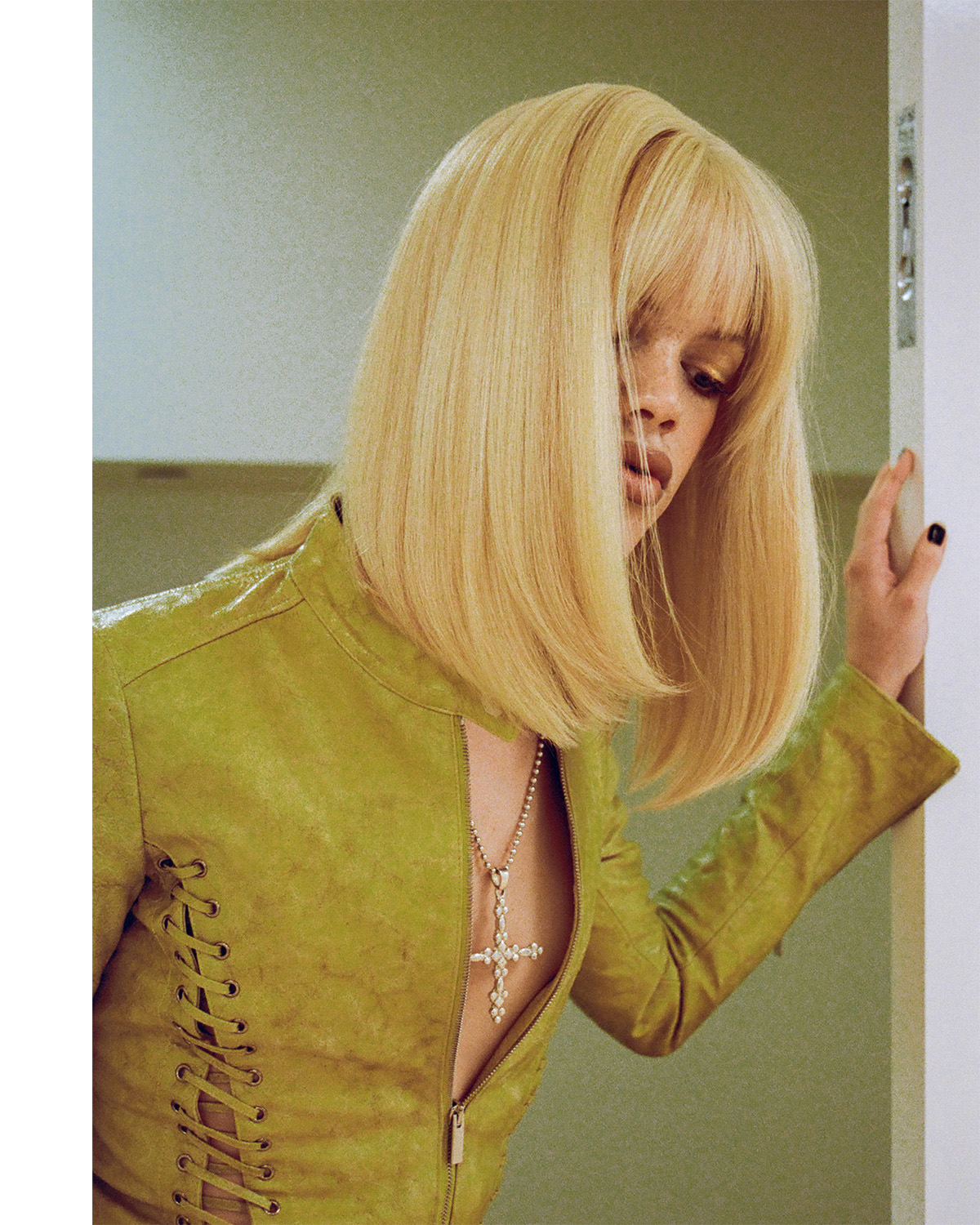

Staring at the People in Prospect Park with genny!

Spoken with a sense of modest earnesty long focal to his lore, the plan makes sense coming out of his mouth. It’s just that there’s one crippling, damning roadblock: “...How do I talk to someone at Xbox?,” he says, with a burst of laughter. He quiets down, and turns his steely gaze, searing through Urkel-esque tortoise-shell frames, back towards the road. “I have these crazy ideas,” he admits, solemnly. “I hope to one day, when I have them, have people say ‘Hold on, let me actually listen to him.’”

These days, a good amount of ears are perked. A few weeks ago, Evans, who used to drop one-off loosies under the moniker “foghornleghornn” before switching over to “genny!”, independently released 8 SONGS, a far-ranging debut album that somehow manages to squeeze chopped-up baptist-church chipmunk soul, transcendental Yoshi samples, and funk-inflected digi-core raps into 22 scorching minutes. Everything about the record — from its running time, to the mid-joyride artwork gracing its cover, to some of its most thrilling moments — points a finger back to an elusive sense of haste. It's a value doubled down upon by its title: 8 SONGS may register as impulsive, because in some ways, that’s exactly what it was.

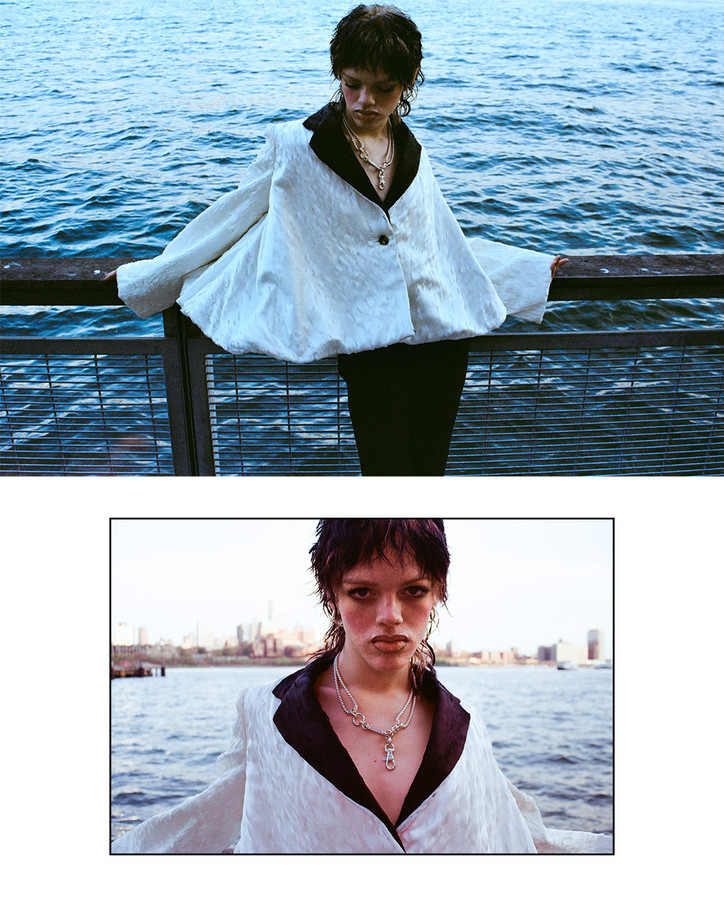

Two weekends ago at the cozy Brooklyn bar Gold Sounds, Evans performed his own music live for the first time on a bill consisting of, among other upstart skate-adjacent acts, Florida skater-slash-rapper 454, and gritty New York spitter Niontay. A matter of days before he graced the stage in a McDonald’s-branded NASCAR baseball cap and a burgundy wig, he had considered quitting music. “Right before I dropped, I was like ‘Man, I’m about to quit music and everything,’” he says, meeting me across the street from the towering Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch, and beginning to lead me down a lengthy route that seems familiar. “Because I [had] been sitting on it for so long, stressing myself out. But having that show forced me to put it out. I didn’t want to do the show without having stuff out. I didn’t even care at that point. I felt like it was the right time. But I at first didn’t feel like it.”

And for a while, he didn’t have the necessary patience, either. One evening back in December, Evans was grinning in the endearingly-cluttered studio room of his Bed-Stuy apartment, prefacing selections from a desktop bearing hundreds of audio files with brief, spoken blurbs about the various projects he had mustered the inspiration to start, but lacked the follow-through to finish. He played early versions of “REGAL” and “ZOINKS!” on a floor-rumbling speaker, contemplating whether, and how, to rearrange certain verses, put lyrics where there weren’t any, or revamp the sonics of musical undertakings he already had a footprint on. Something Evans believes to heart is that he’s here, on planet Earth, “to inspire people,” and for a long time, much like that afternoon, the fuel for such inspiration remained trapped within his four walls. This happened for a variety of reasons: maybe for music, he was stuck in a cycle of perfectionist edits; maybe for fashion, the attention span (and finances) necessary to support Humble, the folk-legend streetwear brand he founded with Conor Prunty years ago, were at a low; maybe with art, more paintings were being started than completed. But across all mediums, the consistent factor was that baggage was being accumulated — and just when he’d venture towards getting rid of one heap, another would always present itself.

“I wouldn’t be able to work on other things, on my own, as well as I can now,” he says, channeling an analogy that likens his cluttered creative headspace to a messy room. “Because I would just be thinking about my messy room. It’s harder to work on other things, because I would always be like ‘I should be cleaning my room.’ I’ve sat on this project for so long. That’s what this project felt like. The room keeps getting more filled up, and more filled up. Now, I feel like it’s clean a little bit.”

Sonically, 8 SONGS sounds like what the disparate bowels of a freshly-used vacuum might look like, broad nuggets of sonic ephemera juxtaposed with one another in a way that’s as enthralling to consume as it must have been to create. (With a smile, he mentions that a friend told him he “invented a new genre.”) On “hostess,” a bubbly number that boasts a masterful combination of slinky auto-tune tenors and layered bass riffs likenable to meat falling off the bone, he skirts his way around playful tales about how he eats “the motherfucking cake like it’s hostess,” boasting endearingly about his love being big enough to fill a mansion, and lamenting with tongue-in-cheek flair on the perils of everyone being the same (“but not me, though”). The following track, “FEELING” — a sped-up version of which was previewed in the outro of “hostess”’s music video this past May — features churned-out, slow-burn waves of reverbed electric guitar foregrounded by mellow vocals, not too far in nature from the skater-slash-musician’s reserved speaking voice. It resonates like the sort of lighthearted, city-bred living limerick Patia Borja references when she captions patiasfantasyworld posts with “#nyc”: “Feeling all the emotions," he narrates in its opening verse, "Still balling and boasting / She calling me a hoe / Sorry I don't even know / What your girl said she saw / Is they friend? Is they foe? / Will I land? Will I fall? You be playing on the low.”

Both sonically and lyrically, the most somber moment on 8 SONGS comes in its opening track, “REGAL,” which Evans recorded alongside his younger brother in the wee hours of the morning while his mother dealt with a health scare during the pandemic. He sounds like a ghost. The song’s instrumental backing — sampled from the Nintendo 64 game Yoshi’s Story, and featuring, if you listen closely, his little brother humming along — hinges on warped moments of tension and release, Evans’ funereal murmur bridging the gaps between life and death with lofty, directionless existentialism. “When the steam blows, where will we go?,” he asks, denatured strings echoing his disorientation. “Can we go by the rocks at Prospect Park, sit and stare at the people?”

Today in Brooklyn, the answer is yes. It’s exactly this that lies at the end of the winding thirty-minute walk that started with Evans meeting me at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Arch, cutting through lawns and rocky roadways, dodging summer camp cohorts rife with rugrats in bright T-shirts, and navigating through greenery-laden shortcuts. At some point, he slows to a near-stop and gestures toward a railing overlooking a quiet lake. Sitting next to me on the banister, he periodically gets up to squash charred joints against the pavement, looking down at the water every now and again to observe large swans and their interactions with very small turtles who swim in bunches around them.

“I feel like I’ve always attracted people who I felt were just truly themselves,” he says, as a bunch of summer campers straggle behind their counselors to gawk at the sea creatures. “They would inspire me, and I would inspire them. I feel like it just happens by being naturally you. If you are just naturally, unapologetically you, you are going to inspire me. And I think that same thing is transferred with everything I do that inspires people, no matter what it is.”

For a majority of those familiar with his story, the first facet of Evans that proved broadly inspirational was his skating. Hailing from a generative batch of scrawny homies-turned-legends who flocked Brooklyn’s skateboarding infrastructure and frequented Tompkins Square Park, he forged a niche online legend with personable clips uploaded to an intimate, impulsively-titled YouTube channel called foghornleghornn, and the aforementioned streetwear brand Humble he co-founded alongside Conor Prunty. In one cinematic short titled “Genny’s Day Out,” uploaded to the foghornleghornn channel in 2017, he navigates the streets of Brooklyn like a 21st Century take on Forrest Gump, skating from impromptu run-ins with boisterous friends, to brush-ups with rushy modeling scouts who assure him they’ll make him a superstar, to charming moments with newfound romantic interests. By the video’s final frame — a modest floral offering of his fluttering into Humble’s equally-modest hand-drawn logo — it feels like, corny as it may sound, the cliche made apparent through its messaging rings true: the only one keeping your life from being interesting is you.

Working at Supreme’s Lafayette Street location for years upon leaving high school, Evans briefly skated for the team, his beanie-clad, Cookie (a la Ned’s Declassified)-esque image reigning in a welcome sense that the sport wasn’t solely reserved for swagged-out cool kids in designer wear, but anyone comfortable enough in their own skin to do it their way. In 2020, he took the do-it-yourself gospel into his own hands: within 24 hours of stumbling upon the Wikipedia page of his estranged grandfather, the Panamanian jazz musician Carlos Garnett, and mustering a long-churning passion to pursue music on his own, he quit his job.

Two years removed from the decision, things are beginning to make more sense in retrospect than they may have as they were happening. The sentiment isn’t lost on the music. “Now, even looking at the album artwork, I’m just like ‘Wow, this is such a fragment of my life,’” Evans says, grinning. “It’s my first car, my first project… I look at this Yoshi [plush] all the time… Everything just low-key randomly fucking worked out.

“It just made sense,” he continues. “When I made the ‘REGAL’ beat, I didn’t even have a car yet, but I could hear a car door closing, so I added that and it made sense. And then, I didn’t even think about it, but I was just like ‘’toeonthegas’ has to be next.’ But now that I’m thinking about it, ‘toe on the gas’ is like starting the car. And the Yoshi sample is in that, and that’s what I’m looking at on the dashboard. Then the colors remind me of ‘simple’ and ‘MILAH’S POEM’ and ‘REGAL’ — the color of the painting is the color of those songs, to me. But then the sun in the back is more like the end, like ‘hostess’ and ‘ZOINKS!’. It all just made sense. But I wasn’t thinking about it this deeply when I was making it… I was just making it. And it’s fucking crazy how that shit happens.”

Creativity is inherently indebted to a similar brand of entropy, and for Evans, the wide-ranging creative impulses he felt as a kid are now beginning to materialize into something concrete. But as much as the imagination may be sustaining itself with more flecks of maturity, the kid in Evans still has yet to go anywhere. Cruising down the lively neighboring streets of Prospect Park in his Nissan Rogue to drop me off at the Eastern Parkway/Brooklyn Museum Subway Station, it’s this version of him that rails off ingenious idea after ingenious idea, threads of scatterbrained youthfulness visibly beginning to latch onto spindles of aged reasoning.

At one point, he tells me he wants to someday have a solo art exhibition. “I’ve been in a lot of group shows when I was younger,” he says, the failed kickflips of a practicing pre-teen skater slapping against pavement in the near distance. “And those are fun. But it’s usually more of a reason for people to get together, get fucked up and hang out. It’s fun, but I’m so over that shit. I want to do something that has some passion and some meaning behind it.”