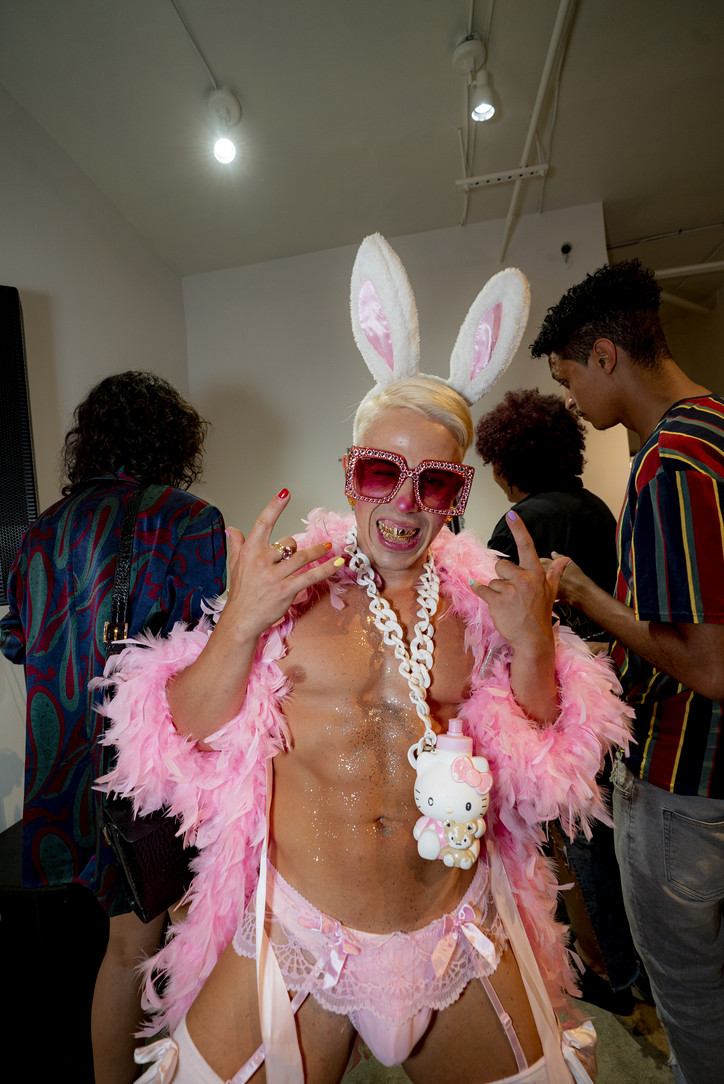

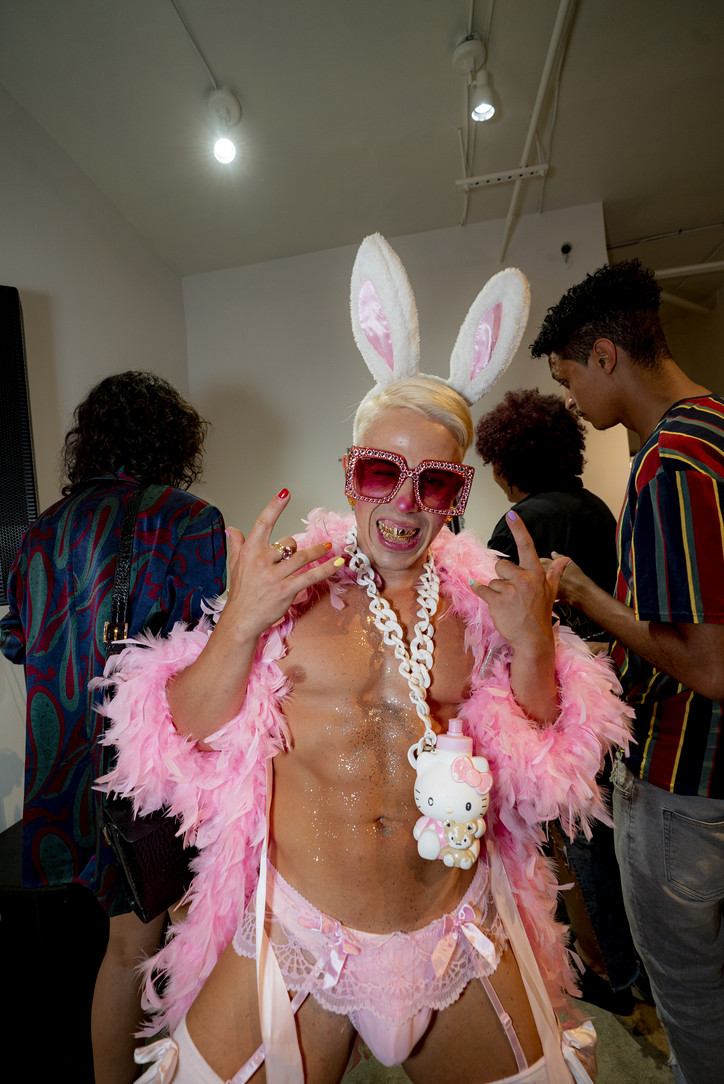

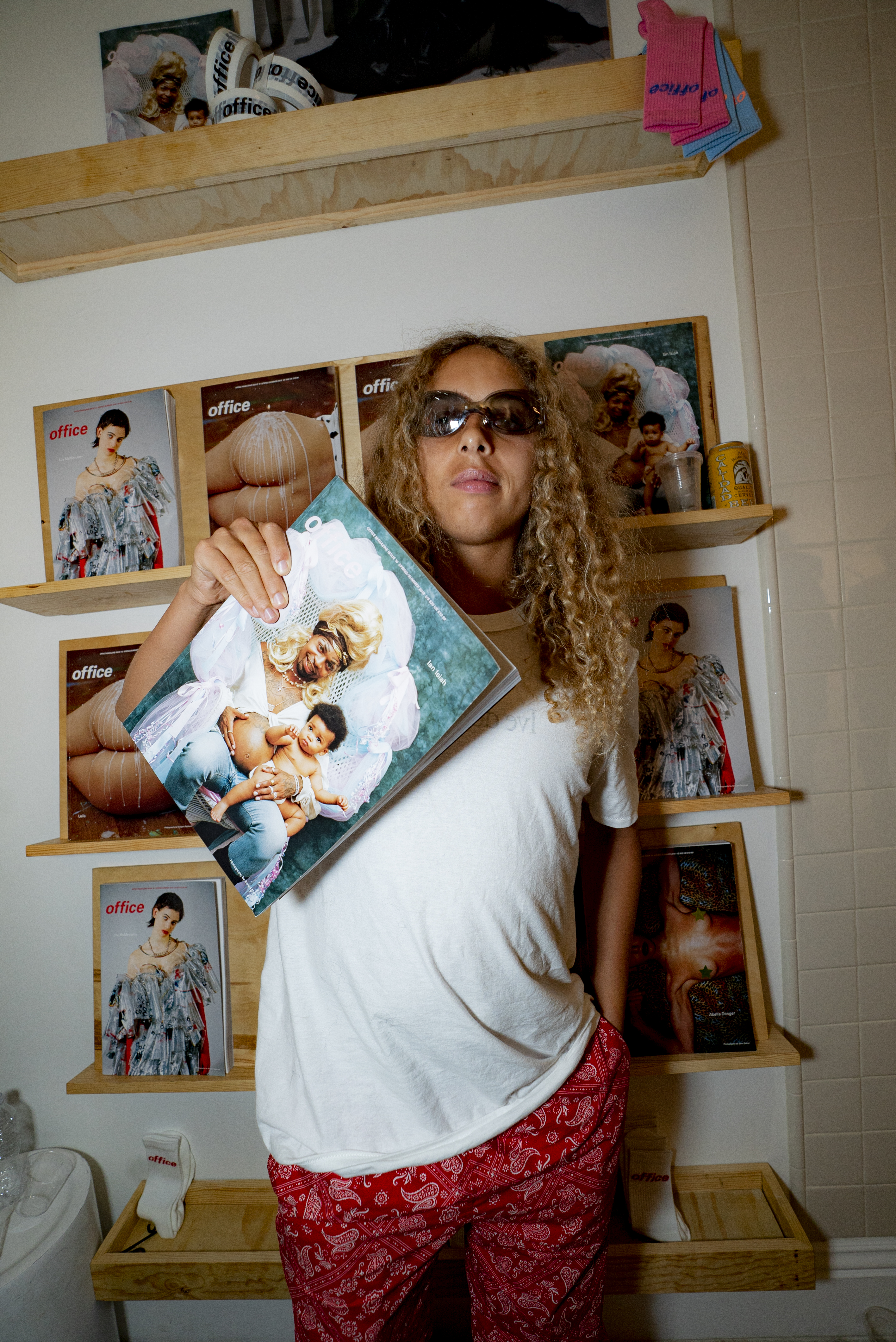

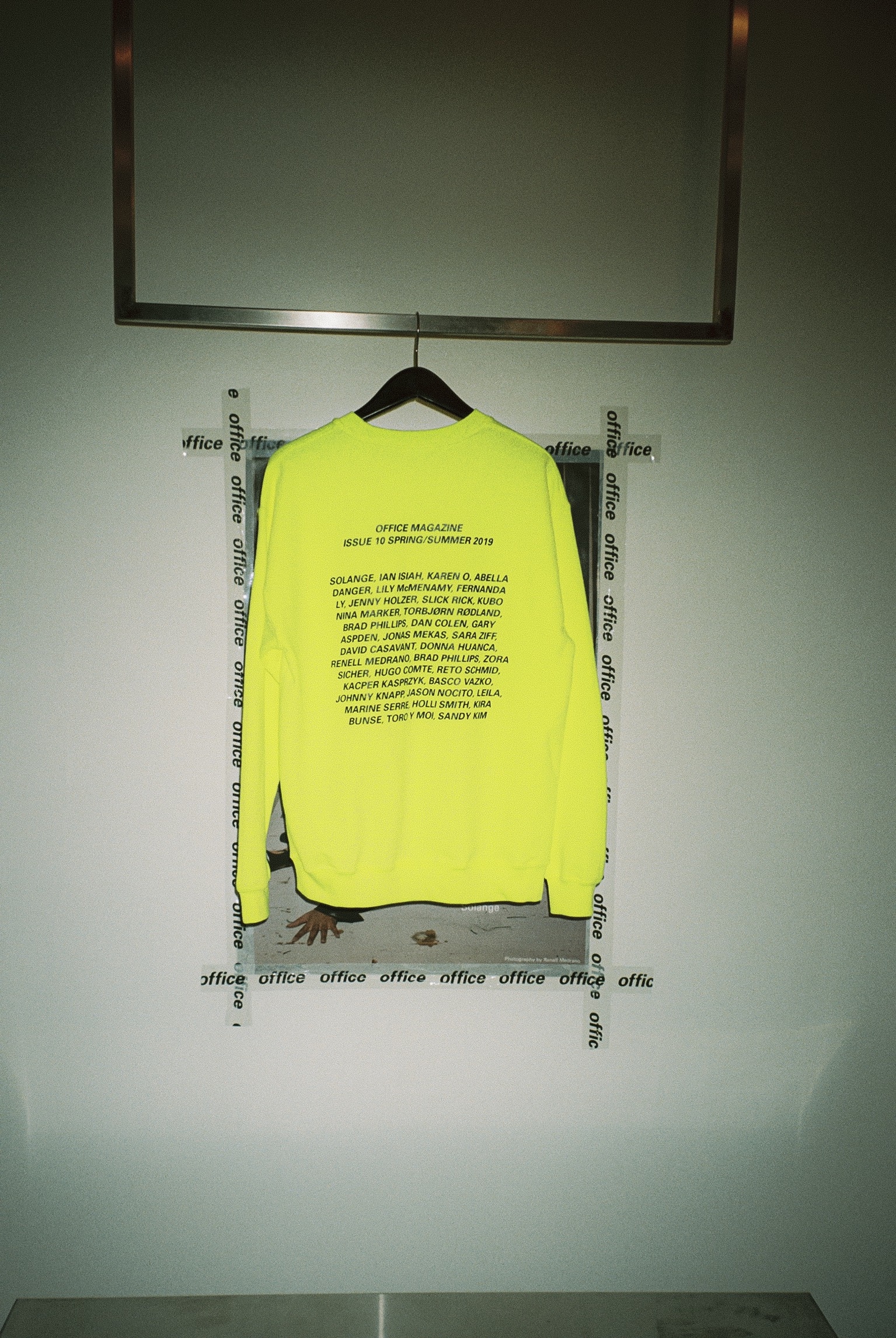

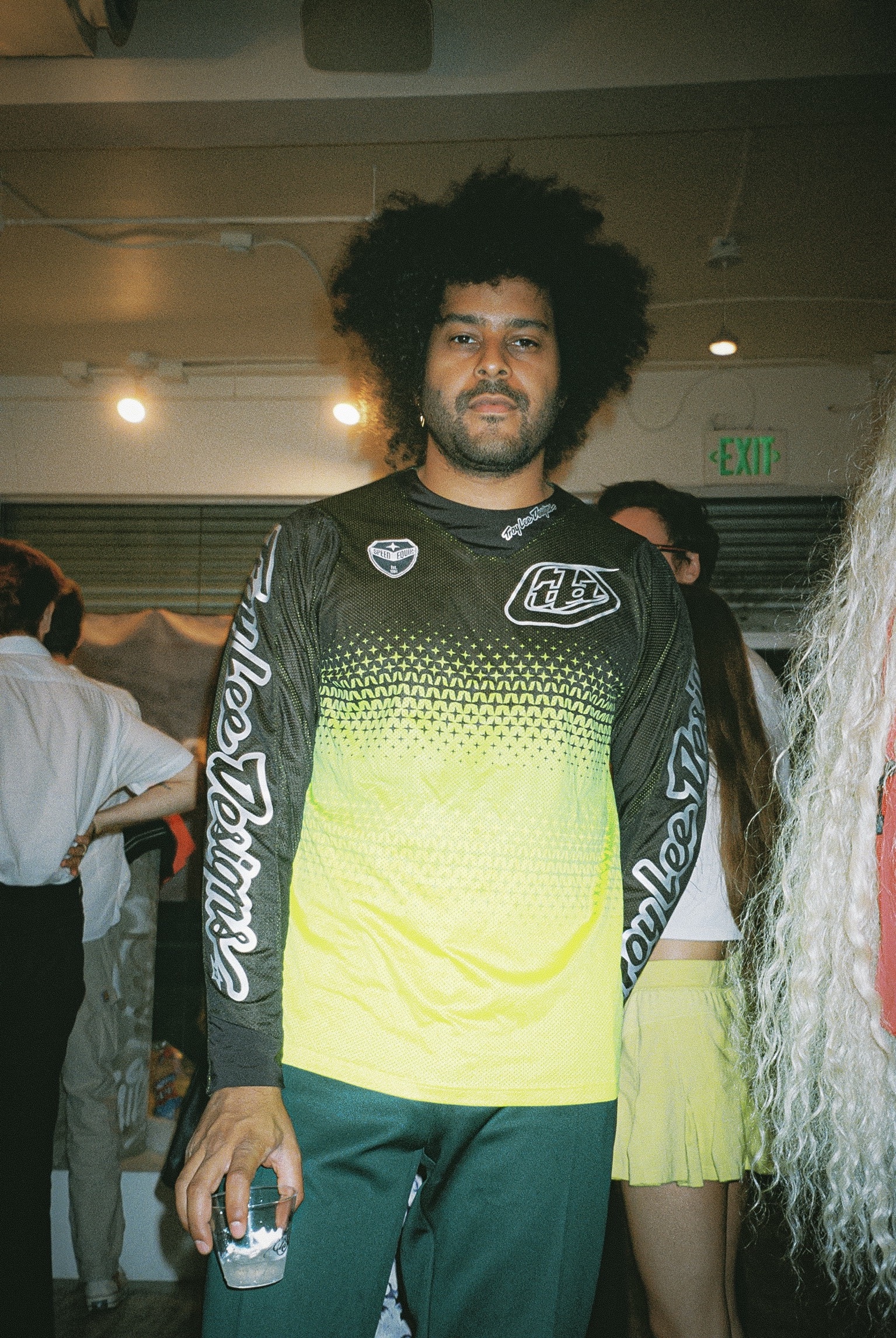

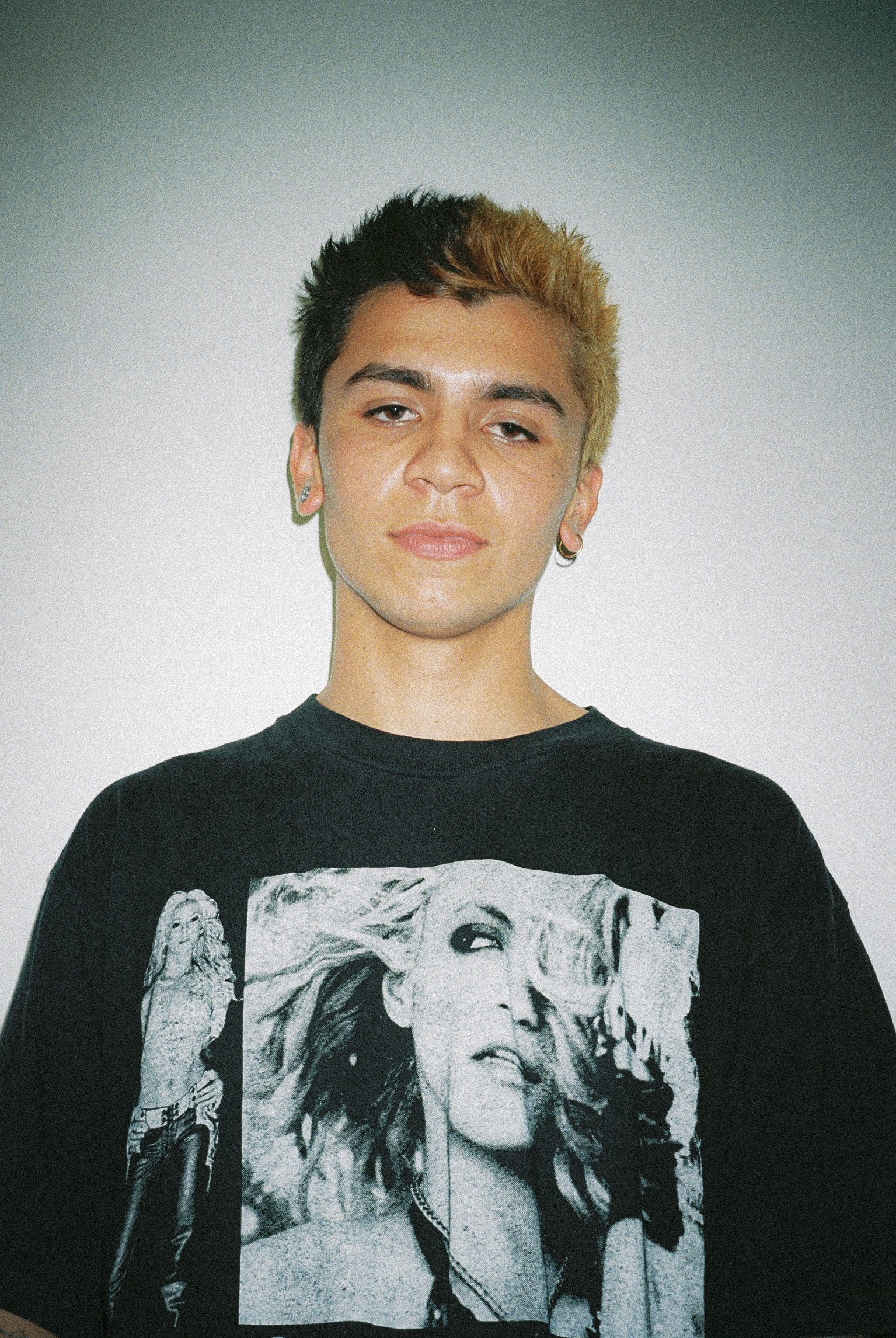

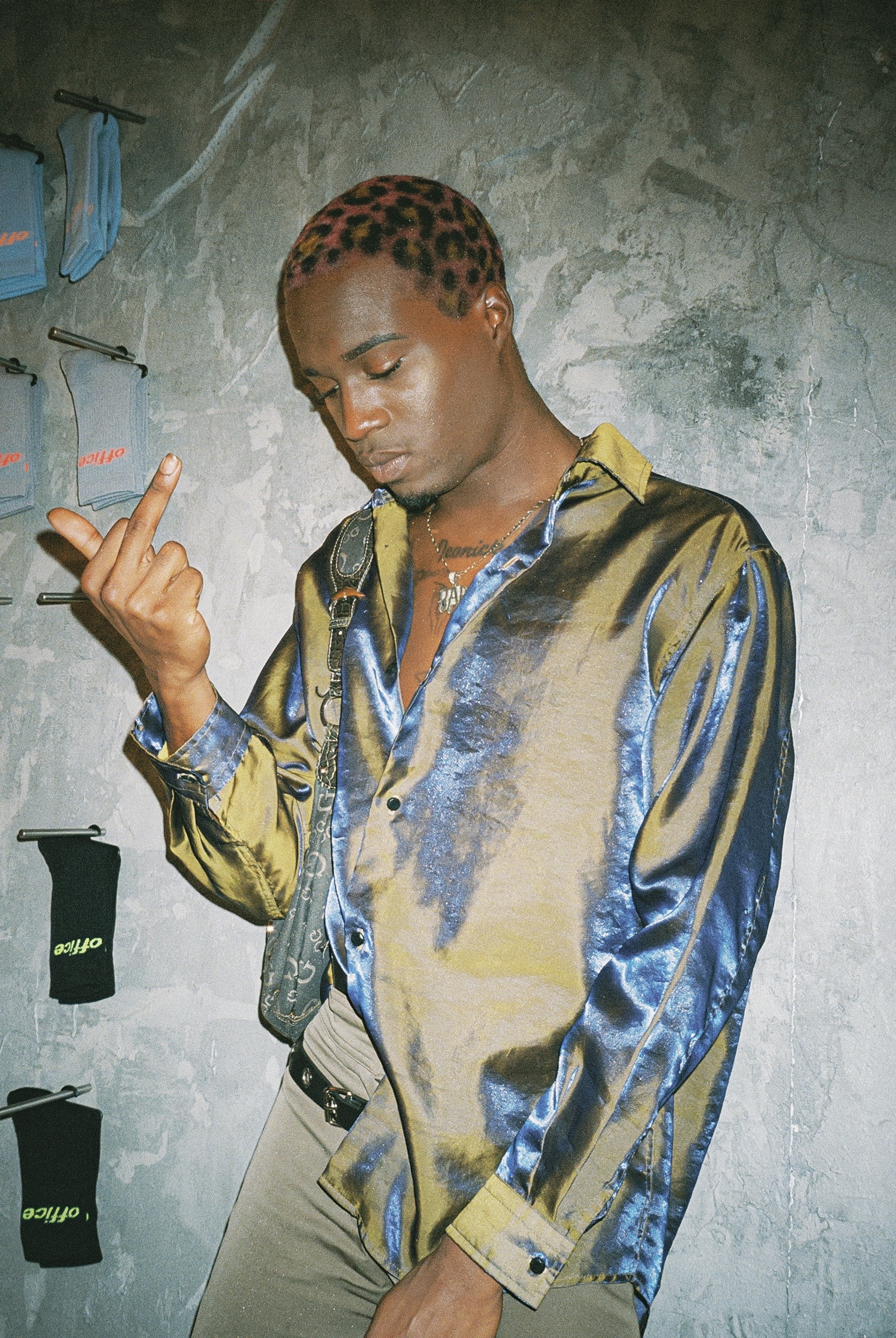

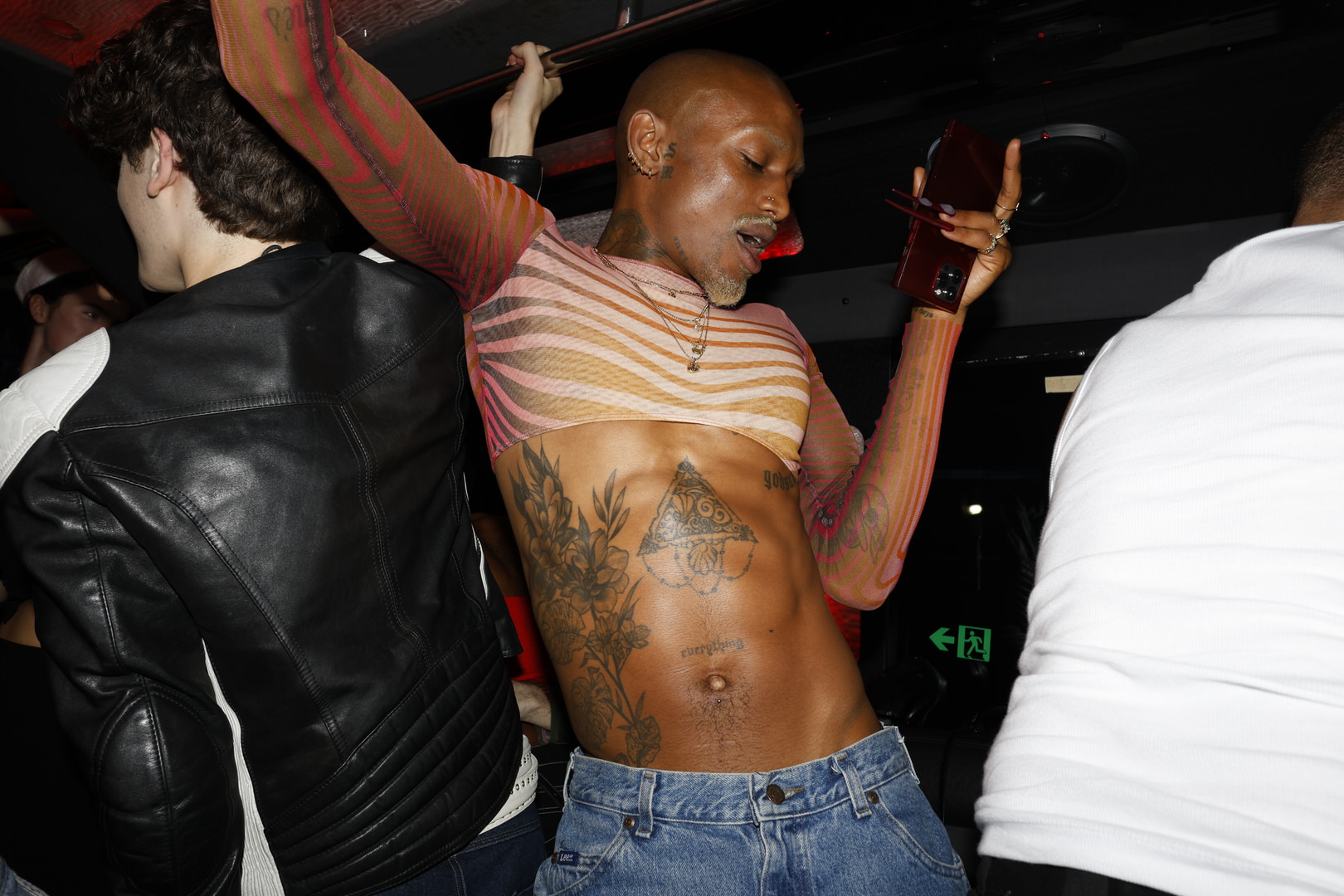

office: LA Edition

Check out some photos from the event below and come visit us on 424 Fairfax, LA—we'll be here for a while.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out some photos from the event below and come visit us on 424 Fairfax, LA—we'll be here for a while.

Leading up to sets featuring Tinashe, Arca, Horsegiirl, Slayyyter, Julia Fox, Bob the Drag Queen, and more, we sat down with Rayne Baron — the literal mother known as Ladyfag — to reflect on the past iterations of the festival. We talked heels, health code violations, and how to throw a good party.

How are you? How's your month been?

Ladyfag— Busy in the best way possible. Pride is always fun for everyone, but obviously it’s more work for me than for most.

I know it’s a little early, but have you been to anything good this month?

Sadly, throwing parties makes you miss out on a lot of partying. I’m in the thick of trying to get everything ready for everybody else. So it kind of limits the amount of partying I do.

It’s a marathon, not a sprint.

Exactly. It’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to.

So true. Where are you from? Did you grow up in the city?

No, I’m Canadian. I’ve been here in Brooklyn for nearly two decades, so I definitely feel like I’m a New Yorker now. I’ve been in New York since early 2005 and I started working in nightlife about a month after arriving. So I’ve definitely done my time — seen the ups and downs and changes and participated in nightlife in all the different ways, from bartending, doing door, go-go dancing, throwing parties, promoting for other people, producing — I was doing anything that needed to be done to make a party happen. I’ve seen it all at this point.

Before I came here, I was in Toronto doing nightlife in a different capacity. I didn’t throw parties, but I used to MC and go-go dance with a promoter named Will Munro — he was a huge inspiration to me. I have his name tattooed on my finger to make sure that everything I touch is touched by his ethos. He died a few years ago, but he had this super queer punk DIY spirit and he was incredible. He did a party called Vazaleen and that’s where I started. One of our mottos is, “An army of lovers will never be defeated.” That comes from Will Munro, which comes from an old queer zine back in the day. I think anyone who came out of any kind of queer scene in Toronto knew him. He’s definitely an inspiration to a lot of people. He taught me the kind of nightlife I wanted to be a part of. Obviously, what I do is very different than what he did. But at the same time, our careers have similar trajectories. I’d like to think he’d be pretty proud of what he taught me. He taught me you have to build stages for people, especially people who don’t think they deserve a stage. I take that seriously.

I’m surprised to learn you aren’t from the city. A lot of people talk their shit about transplants and sometimes for good reason. I think there are a lot of people who come here for school, party for four years and then leave — they think that New York is a place where you can go to vacation and never have to give anything back.

I think New York is the opposite — it’s a really bad place to vacation. If you come to New York, you better wake up in the morning and give it your all or go home. It’s not a city that’s kind to people just doing nothing. It’s that whole, “If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere,” idea — that’s because people come here with dreams and they wake up every morning to try and make their dreams happen. I can think of a ton of other cities where your life would be much easier to live, and the quality of life would be a lot better. I don’t think vacation is something that New Yorkers know too well.

I think people really appreciate when people come here from somewhere else and they choose to stay here, and they choose to give something back.

And sometimes it’s hard. But there’s no city like New York, or there aren’t many cities like New York, where the energy is so alive. And that’s what makes New York so exciting to live in. It can also make it difficult because everybody’s busy in their own worlds trying to make a million things happen. But even though it’s difficult, the city is really open and welcoming to transplants. Because if you’re bringing something to the table, no one’s going like, “Oh, who’s the new guy.” It’s more like, “What do you have to bring?” It cuts out the bullshit, because at the end of the day, people don’t always have time to sit and talk if you’re not bringing something to the table. And in a city filled with people trying to make big things happen, that’s not a selfish thing.

You came in 2005 — it’s not like queer nightlife wasn’t already a thing.

If anything, it’s the opposite. Nightlife was definitely on fire at that point. Obviously, it was pre-social media days, so you had to go out eight nights a week if you wanted to know what was going on. Obviously, that’s changed. New York nightlife is incredible right now — it has its little ups and downs, but it’s a really amazing, vibrant place.

Nowadays — I say that as if you aren’t also partying right now — there are a lot of young people who might also be new to the city, and they’re trying to recreate the New York of the 80s or 90s. I think everyone forgets that there’s already a scene here and they’re trying to reinvent the wheel. It doesn’t seem like Ladyland is trying to do that. It seems like you found something that might have been underrepresented at the time.

There were some things like Ladyland — definitely the LGBTQ+ Music Festival, but those were more like circuit parties with a pop star or a few performers. There was nothing like it and I was confused as to why. Maybe somewhat naively, I tried to do one, and it worked. I don’t know if being naive helped. It was harder than I thought it would be, but I realized that it was the right thing to do. Because we’re on our sixth run and it’s grown so much. Now it’s two days and over three zones under the K Bridge, which is an amazing venue. And now that it’s larger and longer, I can put more and more amazing queer talent onstage. Seeing everyone excited about this lineup, seeing what each artist brings to the table — that makes it worth all the stress.

It’s an insane lineup.

Thank you. We’re pretty proud of it. People always ask us who we’re most excited about, but I’m excited about everyone, because they’re all in different stages of their careers. There are going to be a lot of small artists here that have never played a festival. And there are a lot of larger artists who tour and festivals give them an opportunity to adapt and create special little moments with their fans. That’s what’s always exciting about all festivals — Ladyland included.

And why wouldn’t you book them if you weren’t excited for them all?

We had Tinashe a few years ago. And she’s such an incredible performer. I mean, she had trampolines for fuck's sake. She really did it all for everybody. We don’t always like to have the same performers, but obviously she has one of the big hits of the summer and she’s a dancer — she has such amazing live energy. Knowing what the hell she’s going to do, I’m still excited for her set. And we have Arca — who’s performed so many different versions of herself — from live shows to DJ sets, you never know what she’s going to bring to the table. And that’s what keeps it exciting.

Lucky Love is coming from Paris just for Ladyland. He’s incredible. And there’s Rahim C Redcar — formerly known as Christine and the Queens, who’s doing their first-ever hybrid DJ set — I’m not even completely sure what it is, but they asked for a mic and have been sending me little clips of music that they may end up leaking at Ladyland. Again, I don’t know. And that’s what’s fun. You obviously want to support your artists and let them do whatever they want on stage — step back and see what they do. It’s going to be an exciting week. Especially when people don’t always have an opportunity to see artists like this.

The things that make me happiest are the moments after the festival when I get some time to breathe and sit with my friends and people whose opinions I respect. We sit there and decompress and you know — drink seven bottles of wine. And they talk about the artists and say, “Oh, I’d never heard of them but they were so amazing.” Moments like those are why I do it. Obviously, there are icons onstage who everyone’s excited to see, but you pepper it with people that maybe people haven’t heard of before. I’m trying my best to make sure there’s something for everybody.

I mean, I wear my platforms to every show because I like to see, but if I know there are going to be so many good acts spread out across the area, I’m wondering, “How am I going to run to catch every show?”

I just got out of a production meeting, and there was an area in front of one of the stages that had all these pebbles because it’s a park. And we had to figure out the costs associated with putting down more platforms, and some people on the call were like, “Do we really need to have that just for some people in heels?” And I was like, “It’s gay pride. We have drag queens. People will be in heels.” It’s an important thing to not skimp out on budget. We care about you, you heel wearers. I want people to know that we do care and we’re trying our best.

That’s a crazy thing to have to think about — most people wouldn’t.

And it’s not your job to think about it. Your job is to come and not think about anything and have a good time. It’s our job to look at everything as a problem to solve. You problem solve, problem solve, problem solve, and then you have a party. It’s not the other way around. So yeah, my life is one big problem.

Happy Pride.

Happy Pride!

Are you noticing any differences between the reception and organizing of Ladyland number six versus its first iteration?

More money, more problems. More stage, more problems, more divas. Sometimes I wish I could go back to that first season — it seemed so much easier at the time. But the bigger you get, the more expectations people have — and rightfully so — whether it be the guests or the artists. It’s just up to our team to try to work harder to make sure that we live up to as many expectations as we can. The goal is that everyone is happy. Even though you can’t please all of them — especially in a room full of thousands of gay people. Not to be homophobic during Pride—

I don’t think you’re being homophobic, I think you’re being honest.

We do our best to make sure that everyone can have the best Pride ever. The bigger it gets, the less fun I get to have. But I’m okay with that. And I’m really excited about it. It’s really big. And the gays deserve that. But I also think going to a small, dirty gay bar is an incredible thing. And you should support your local dirty, skanky gay bar.

If it’s not a fire hazard, I don’t want to be drinking there.

If you don’t feel like you’re going to die at least ten dimes during Pride weekend, did you really celebrate Pride?

If you don’t have to remind yourself to get a tetanus shot after Pride, you didn’t go hard enough.

It’s really amazing to be able to offer the city something this big and exciting — not to make myself sound like Mother Teresa. If anything, I’m trying to create other spaces for other people to get to be bad girls. I want everyone to have a good time.

It’s really refreshing to have someone who very obviously cares about the people they’re making parties for. We have so many random corporate Pride events that work to just get everyone’s pictures in front of their rainbow logo only to kick them out after.

We don’t have that many rainbows at our festival. I mean, you’re welcome to bring your rainbows. We love rainbows. But that’s not really the vibe. Alongside “An army of lovers will never be defeated,” our other motto is “Fist and resist.” So, we want everyone to be cautious and careful, but constantly fisting and resisting. A little less rainbow flag-friendly.

A little less cops-with-rainbow-batons friendly.

It’s just less family-friendly, except my baby comes to it in earplugs at some point. I’ve walked through soundchecks breastfeeding — making it a family event, but after that, we just keep the baby at home.

It takes a good nurturing instinct to be a good event planner — wrangling all these people together.

There’s definitely something maternal about it. A lot of my artists say to me, “Oh, mom is here making sure that you have water backstage,” so it’s mom vibes, but I’m a cool mom, I promise.

Mother — in every sense of the word.

I’m not a regular mom. I’m a cool mom.

As a student enrolled in pharmacy school in Bangladesh, Hamja became bewitched by foreign films, binge-watching the likes of Korean indie Bandhobi and Italian drama-comedy Cinema Paradiso. Therein began his love for cinematography and, by proxy, photography. He became wholly dedicated to the craft, obsessively immersing himself in the realm of color, texture, light, and composition. With the ability to exaggerate or enhance details that would have otherwise been overlooked, Hamja brings the subtleties of everyday life into sharp focus. By the end of his NYTimes fellowship, his work was featured on 18 covers and four front pages.

Hamja and I hopped on FaceTime one evening in June, and from his sun-soaked Greenwich Village fire escape, he walked me through the trajectory of his career and what it takes to be (what I consider) a legend in the making.

I can imagine that leaving your home country for an unknown place is a daunting endeavor. Who or what did you leave behind in Bangladesh?

Honestly, it's not about who I was leaving behind — it's more about the timing. I’d already tried twice to get a visa to the United States and it kept getting denied. So when the third time came around, I was already working with our prime minister in Bangladesh on a big biographical documentary. I was very happy with how my life was going back home. After my school increased funding for their portion of the scholarship to the International Center of Photography (ICP), I was able to apply again and suddenly got the visa. I needed to move quickly since I was already late to join the ICP orientation. I literally prepped everything in 7 days and just jumped. I’d studied pharmacy and one of the senior students was like a brother. He always believed in me and had moved to NYC after graduating. It was the only person I knew in the city so if he didn’t answer my call, I didn’t know where I’d be staying. It was do or die. I stayed on his couch for almost a month until I figured out my own space.

See, that’s why I love South Asian culture: everyone becomes family.

Yeah, I can always count on him. Even now, I can call him and go stay at his place.

Pharmacy and photography couldn’t be further apart on the spectrum of careers. When did you get interested in photography?

I finished pharmacy school because I didn’t have any other option but I knew, in the second year, that I was going to be a filmmaker. I was watching a crazy amount of movies during that time and felt like it was something I really wanted to be a part of. I couldn’t pinpoint what it was but slowly figured it out. Color. Light. Composition. The way the camera moves. It was all so exciting. So I made a plan. I downloaded a bunch of eBooks and learned that if you want to be a cinematographer, you need to be a good photographer first. I taught myself everything. I figured everything out on my own.

You’re a hustler! Did you, at any point, think about quitting?

No, there is not a single moment in my life when I thought about quitting or doing something else. This is it. This is what I want to do. I don’t care about anything else.

What’s it like to know exactly what you want to do? How does that feel inside?

It’s like having tunnel vision, which has its pros and cons. I never tried any other art form after that. Maybe I’d be good at something else but I wouldn’t know. I never wanted to try because I was so focused on my own goal. Early on I knew I wanted to have 100 percent ownership of my own life. I want to make my bread and butter — everything — from film.

When you’re on the road, what can’t you live without in your kit? What are you always carrying with you?

Most of the time I carry a 50mm lens. However, nowadays things have changed. The way I see things has changed. I’m happy just going around with my phone or using any camera.

What about when you’re looking through a lens — how do you know when it’s the right moment?

Sometimes you try to read about the subject before. Who is the person? What do they do? Do a little research so you can have some sort of conversation with them. From there you can build your vision. If I can scout the location before, that’s great. But on set, when I’m shooting, things change. Suddenly, I see some light or a wall or something. It’s all random —- I cannot control those elements.

You recently wrapped up a prestigious fellowship at the NYTimes. What will you tackle next?

I want to shoot more portraits. More art and culture-related work. I’d love to push myself towards magazines more.

Do you have any advice for aspiring photographers out there?

Figure out what you want so you’re not distracted. Once you know what you want to work on, reach out to editors right away. I did it in my own crazy way: emails or DMs on Instagram and LinkedIn. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it backfired.

But you also need to wait for your moment. When you know that you have good work. Don’t reach out with average work — reach out when you’re ready. The way people get assignments has changed now. All of the photo editors I know are active on Instagram. They’re always looking for new photographers. There’s no one way.

You just need to have the passion and the drive.

Yeah, because it’s your world. You need to figure out what you want from this world and what it’s made out of for you.

The polarizing values of seclusion and companionship in Allen’s life are accentuated by the nature of his environment: placid woodlands, serpentine pathways, a big, blue body of water. When I connect with Chamandy through Zoom, he’s eager to contextualize the journey behind the biggest piece of his young career, delving into the myriad of unrelated influences threaded into his process. At the core of his desire for artistic fulfillment is an unfettered admiration for Chief Keef, who, like Herzog, turned precocious spontaneity into world class artistry, infinitely imitated. Last year, Allen Sunshine was the recipient of the TRT First Cut+ Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic. This July, Chamandy will be in Germany for its world premiere at the Munich International Film Fest.

The way Chamandy describes Allen Sunshine is like a soccer dad raving about his daughter who plays striker for the school team; the sheer level of pride shines through immensely. Across half an hour, Harley Chamandy goes into detail about the subtleties that make up Allen Sunshine, what he’s learned about the film industry so far, and the use of music as a storyteller.

Olivier Lafontant— Allen Sunshine largely centers around the life of an ambient music producer and former record executive. Where did the inspiration for this come from?

Harley Chamandy— It all began with an artist named Ethan Rose who did all the music for my film. He’s an electronic artist who did music for Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park (2007) and Showing Up (2022) by Kelly Reichardt. One day when I was in high school I had his album called Ceiling Songs and it made such a strong impression on me that I kept listening to it every day, and it sort of got me into that world of that music. When I was writing this script, I always knew that it had to be that type of music, I just didn’t know that I’d be able to work with my favorite artist, Ethan Rose. I was playing his music the whole time while writing the script and once I finished it, I reached out to him [by] cold email ‘cause that’s my thing and you never know what will happen. He really liked the relationship with Allen to the music and that’s something he really wanted to take on, and he thought that was an interesting challenge for him as an artist. I really think [ambient music] is the most introspective form of art and of music, and I really thought that I had never seen that in film, you know, someone really making art for themselves. In a larger context, I think that electronic music is an artform that’s really for the self and what can happen with the instruments. It’s never really about thinking about the consumer, which I was very interested in.

Yeah, especially with Allen in the movie. There’s the scene where his brother sees his studio and asks him what it’s for, and Allen tells him that it’s only for himself. How do you feel like the music itself informs the narrative of the film? How does it represent Allen as a character?

Well I definitely think that it’s a tool that’s used to display the introspection of the character––how he’s feeling, what he’s thinking about––without having to say anything. Just through the music we can understand his state of mind, and how he’s feeling about things. After the brother comes, the music is way more somber, and then when he hangs out with Bill, the man who comes with the fruits and veggies, there’s something more uplifting and optimistic. I thought it was so interesting to play with the headspace of the character in regards to the music.

Considering this is your debut feature film, what are some of the challenges that came with fleshing out a script across 80 minutes or so?

Literally everything you could imagine. They say don’t work with dogs, don’t work with kids, don’t work with fire, don’t work on the water; I literally chose to do all of it. Plus we shot it on film which was another crazy challenge because we shot in Canada, two hours from the city where we were developing, so we had someone drive the film back every day. I think the biggest challenge really was getting people to believe in a young filmmaker. I made the film at 22 and [had to gain] people’s trust, not just on the financial side of things but also on the creative level. Making a film is very challenging but also very rewarding.

You mention shooting it on film and I noticed that within the narrative itself, a lot of the items and tools used in Allen Sunshine are analog: Allen’s music equipment, his film camera, even the housephones. Why did you feel like it needed to be in a time period that represented that?

That was a huge part of the film. I always had this feeling that I wanted all my films to feel timeless, like there was no way to feel what the time period would be. When I was developing the visual language and shooting on film, we had a production designer, but I was so specific on finding my props on eBay and I feel like every little detail mattered so, so much: the color of the housephone, what kind of camera he was using (a Contax G2 ‘cause I think that’s the nicest looking camera), all the synthesizers––that was one of the biggest challenges of the film because it’s so hard to find this gear. I spoke to a lot of costume designers before doing the film and no one could understand what I was trying to say, so I worked with my girlfriend who has never done costume designing before, but she almost spoke the same language as me in terms of what I was trying to get out.

There’s a real pervasive sense of subtlety that moves the plot along and the majority of the narrative is informed through context clues and vague dialogue. Why do you think it was important for the narrative to be presented that way?

I just think that so much art these days made by young people or for young people is so in-your-face and always very edgy and out there. I think that’s totally cool, but I wanted to have a refreshing sensibility for my generation and I wanted to evoke more of a nuance in terms of the sensitivity of dialogue and how to approach things, and really ask the viewer to slow down. That was a really big thing for me. To be honest it’s something I’ve been chasing for so long, this type of feeling.

Does the overarching theme of grief and mourning derive from personal loss? What drives you to write and direct films of this nature?

I never thought the film was a film about grief, but I really thought it was a film about love and what it means to live without it. That’s always how I wanted to approach it. I know on the surface it’s a film about grief, but to me it’s about finding love in new forms. It’s a film about reawakenings, and finding new outlooks on life, and what happens after loss.

How do the characters you write derive from the characteristics of the people in your life, if at all?

Well if we get really deep into the subconscious, I grew up with a mother who’s a musician. I grew up coming home every day [seeing her] in the studio making music. I never looked at it that way, but I think those are always characters I’ve been inspired by: people that were doing their own thing in their own way. Maybe Allen comes from that. But I’ve also been fascinated by the big mogul kinda characters that also have this really artistic side to them, but we never really see it in the media. I think we haven’t really seen that type of character in a film before: a very rich, successful music industry guy who’s also making ambient, super alternative stuff. I thought that was a really cool juxtaposition. I guess with the kids, I feel like we’ve all grown up with the chubby kid with the long hair. It's almost like everyone kinda knew these people somehow or some way.

What was it like submitting Allen Sunshine to the Karlovy Vary International film festival?

I was part of this lab called First Cut lab which is run by this amazing person, Matthieu Darras. Many of the films go on to play Cannes and Venice and the major film festivals, and I was lucky enough to be a part of it. Then they have First Cut+ lab in Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic, which is where we meet with mentors and sales agents, and then we pitch our movie to 300 people. There were eight [finalists] and the jury picked what they felt was the best film. Now we’re world premiering at the Munich International Film Festival in July which is super super exciting. But yeah the submission process is very challenging, especially these days where not just so much about how great of a film you make but there’s definitely a lot of politics involved. I think as a first-time filmmaker with not a lot of industry connections, it’s more difficult than I had anticipated, but I’m really grateful for the journey.

Can you describe the process, even outside of Karlovy Vary, of finishing the movie and now promoting it as much as you have even two years down the line since completion?

What I’m really grateful for is that I’m so proud of this film, I really think that it’s everything that I think cinema should be in terms of the sensitivity, the images, the dialogue. I’m really pushing what I wanted to push, which is this optimistic approach. When I announced my film I said that “to choose optimism is to choose happiness,” and I think that’s really the core of what I think the film is about in a sense. Especially as a young person, I really feel like cinema is dying, and [with] the stuff that’s coming out, people get less and less interested. I think what makes great cinema is having young artists with very strong points of view and aesthetic points of view, and not being so worried about storytelling. That’s what I really think is the downfall of cinema is that we’ve always spoken about it as storytelling, but it’s so much more than that. It’s aesthetic, it’s visual, it’s sound, it’s feeling. I think with Allen Sunshine, what I’m the most proud of is I was chasing a feeling and I wasn’t chasing a plot narrative. I was collecting images when I was 17, 18 of old images from thrift shops, and a lot of the references are high fashion and a Canadian painter named Alex Colvill. [There aren't] a lot of cinema references at all. Now to have it out, I feel like it’s a huge part of me that I’ve never been able to show to anyone.

Could you speak more on the high fashion influences? What particularly about certain fashion labels drew you to making a film like this?

I was extremely inspired by Alexander McQueen and Margiela and the way that they [have spoken] about fashion… in a sense I relate more to them than how filmmakers speak about film these days. This aesthetic point of view that they’ve pushed, this nuance––it’s the sensitivity, the details. And the way that these designers speak about things, and their lookbooks and the images… it feels like they’re always pushing things forward. I think that fashion is one of the only artforms that is always being continuously pushed, and there’s so much avant garde but there’s always commercial appeal. There’s something that I’m trying to figure out with film; is there a way to really get to [where fashion is]? Balenciaga is doing some of the craziest shit artistically, but people are still consuming it. Why can’t that work with film? I think that’s what inspired me. Even Demna, I hear him speak and it’s so inspiring to me and that’s where I’m tryna get the film stuff to go. I just watched the [John] Galliano documentary and I feel so much more inspired by these people. I wanna hear about why you chose this type of fabric, and why this photographer? They always speak about inspiration coming from these deep places and I don’t hear that as much in film. [Filmmakers] always wanna explore culturally relevant things and I’m not excited about that.

How do you envision yourself building off of the experiences garnered from the making of this film and its subsequent promotion?

I think that I learned so much about making movies that I never thought about beforehand. It’s not just about having a script and a film and people that are down to make it, but it’s also about what happens after it, the commercial aspect of it, the international interest. I wouldn’t make the film differently at all because I’m honestly so, so proud of it, but I think [from] a business [standpoint] and a larger global context, I would think about things different. Like trying to secure a more famous cast and little things, you know? You gotta have someone attached to it that’s a bit bigger. I’ve networked so much that I’ve been able to meet the head of Sundance, the head of Venice, but I’ve realized it’s a really large game and you gotta play it right, you know? I think when you’re so young and you’re so passionate, you think it’s you against the world and you wanna make these great films. Then you get to a point where you see there’s so many other factors working. It kinda opens your eyes and you’re like “Damn, I gotta think about the art ‘cause that’s what I wanna do, but how can I make the art more global? How can I get it to more people?”