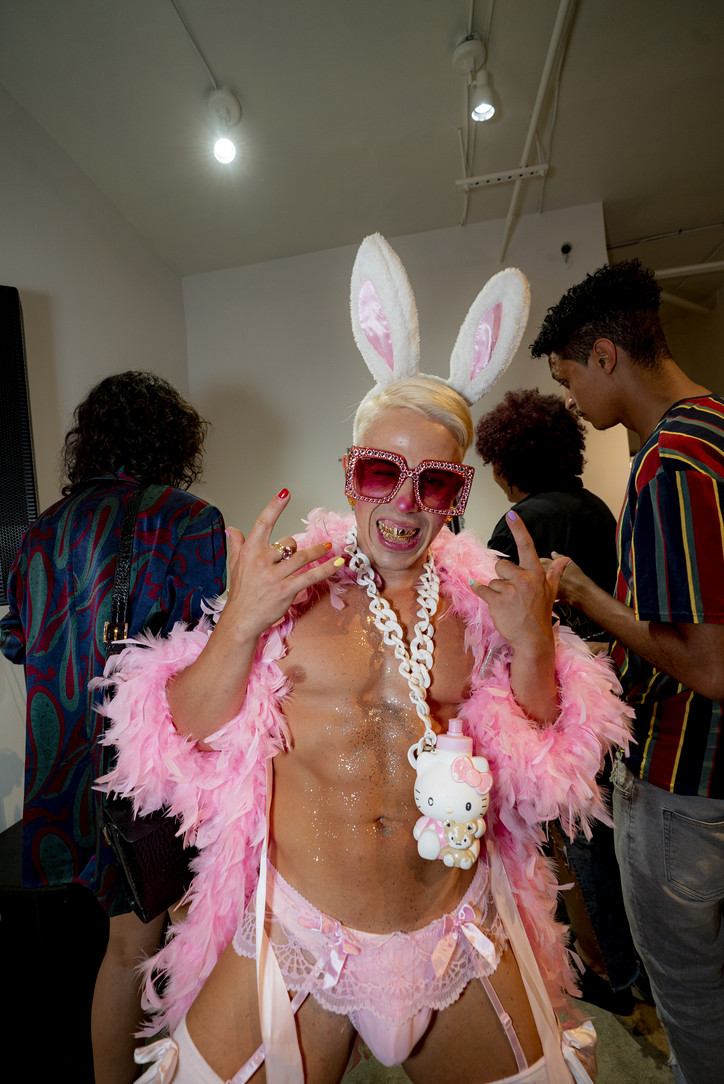

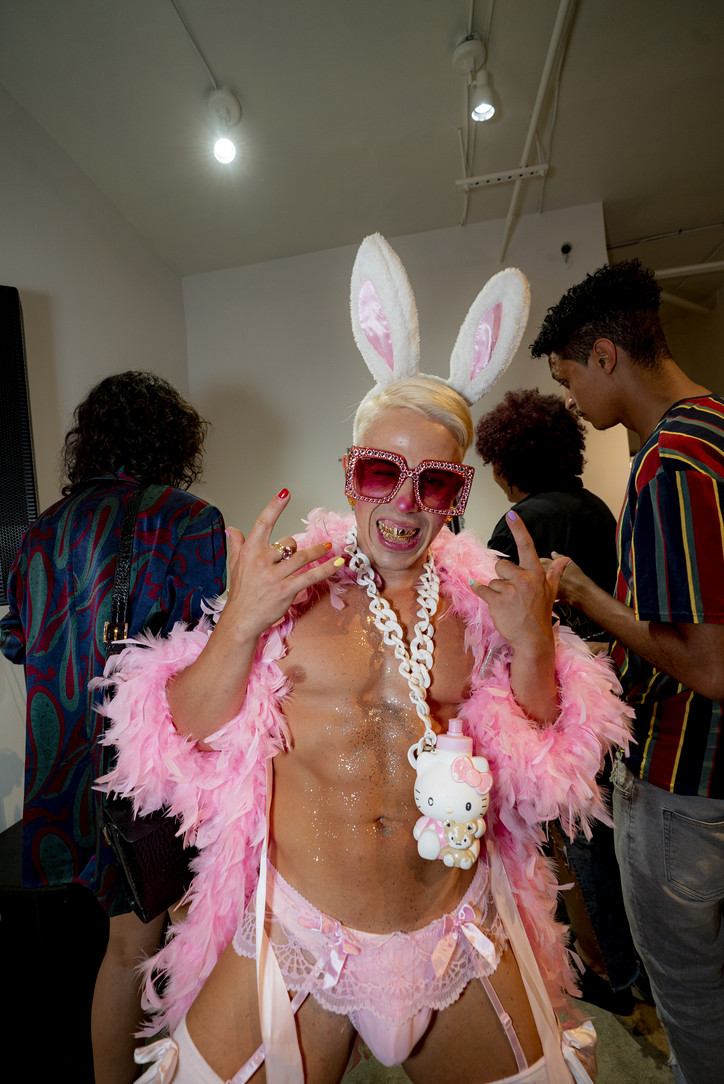

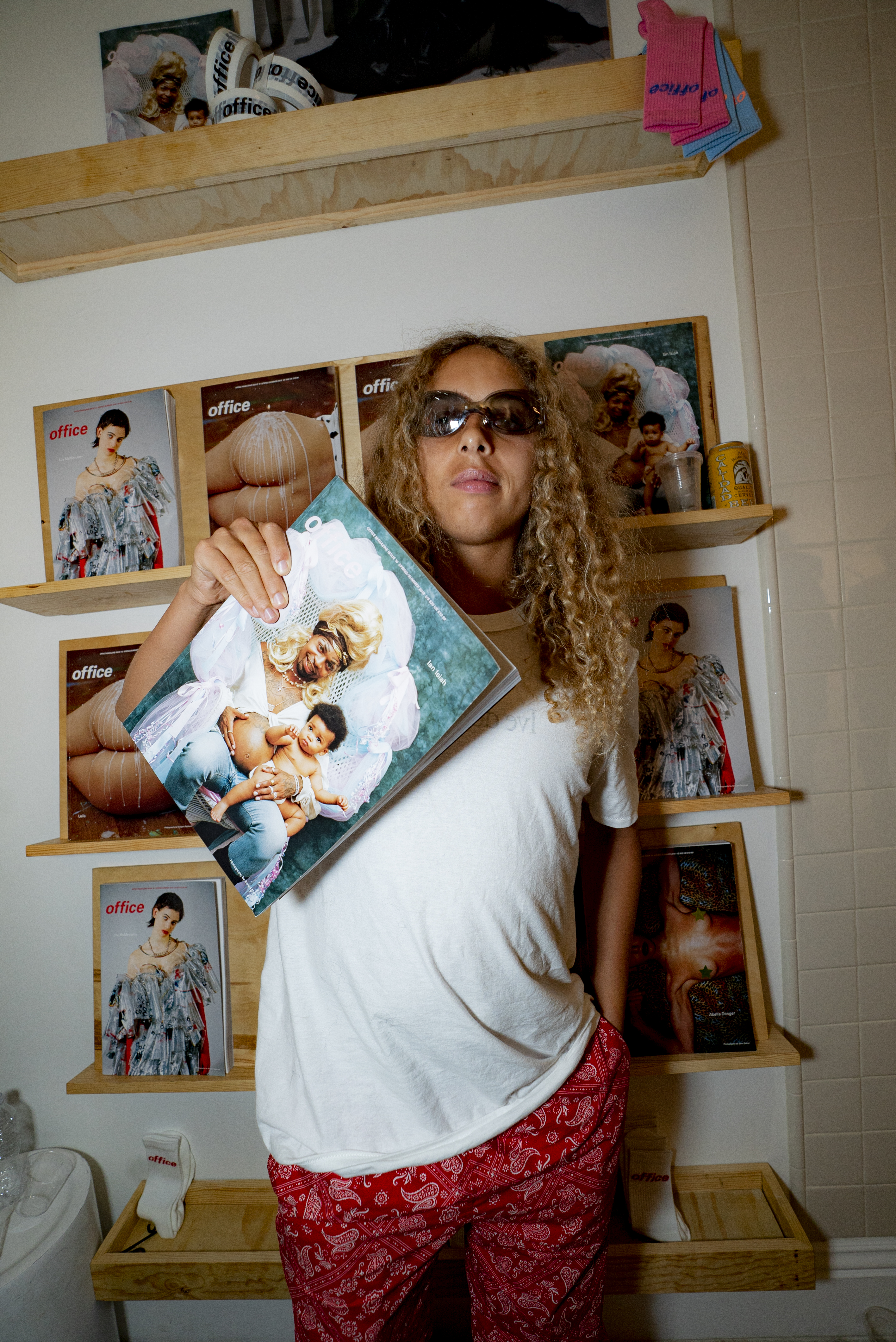

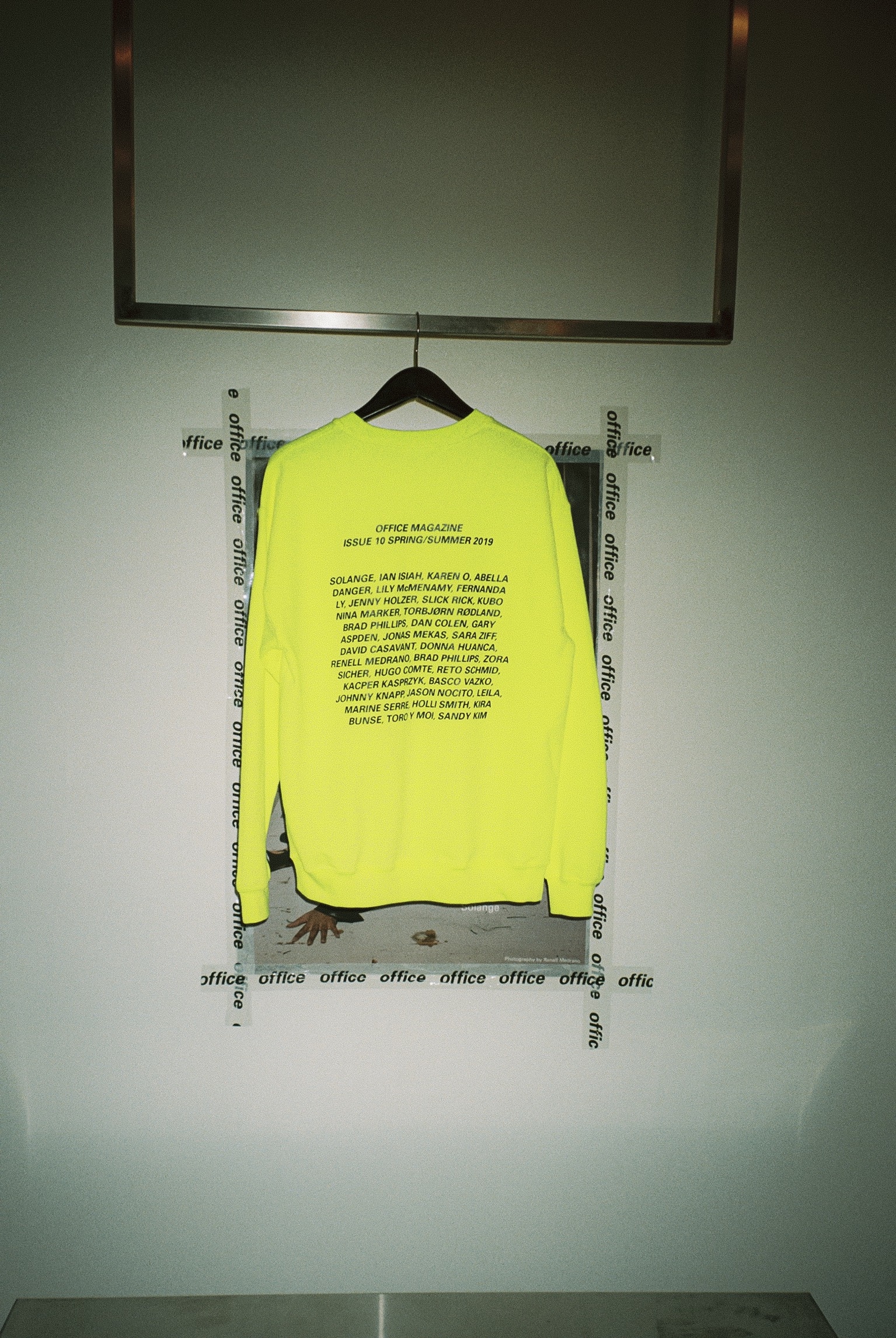

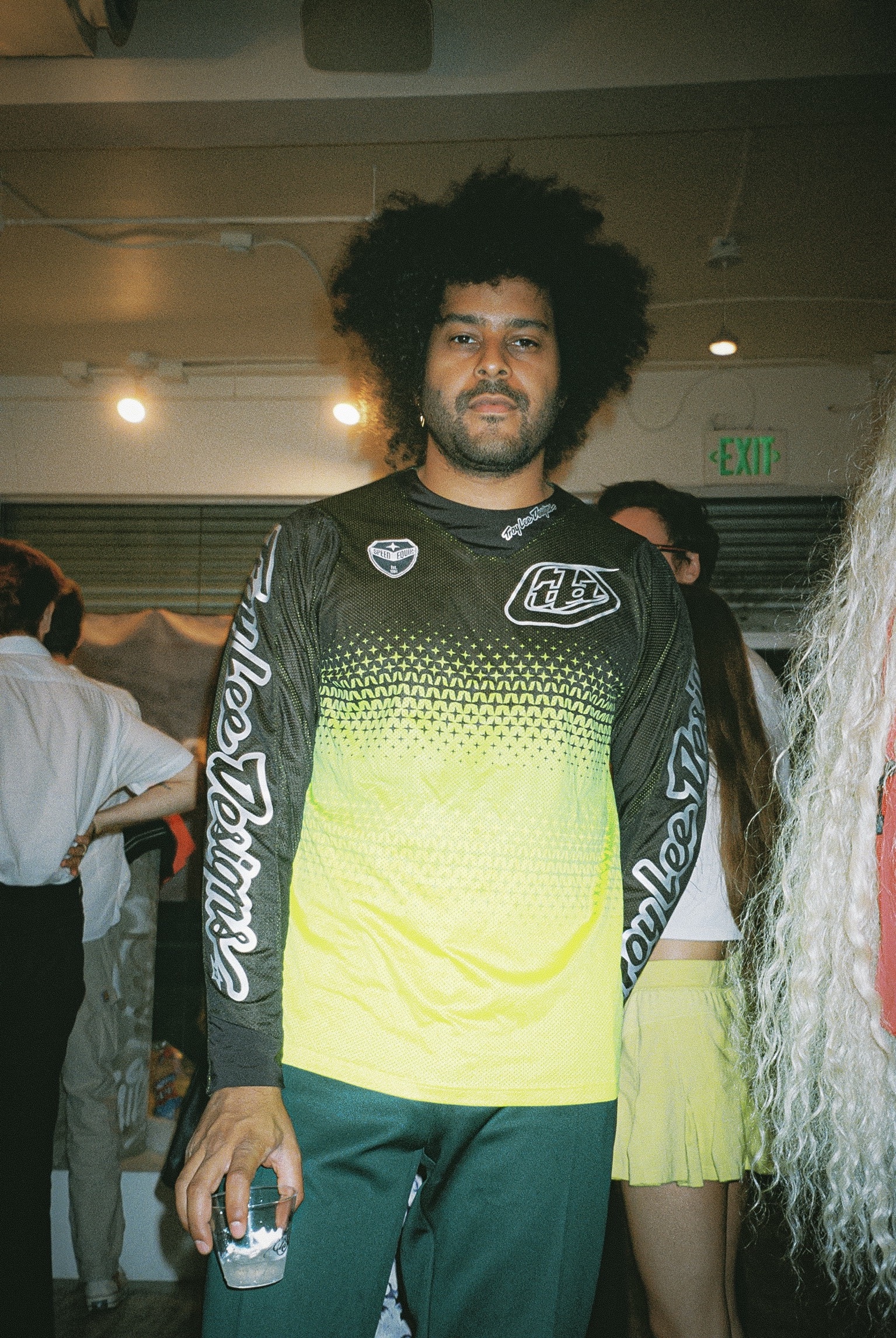

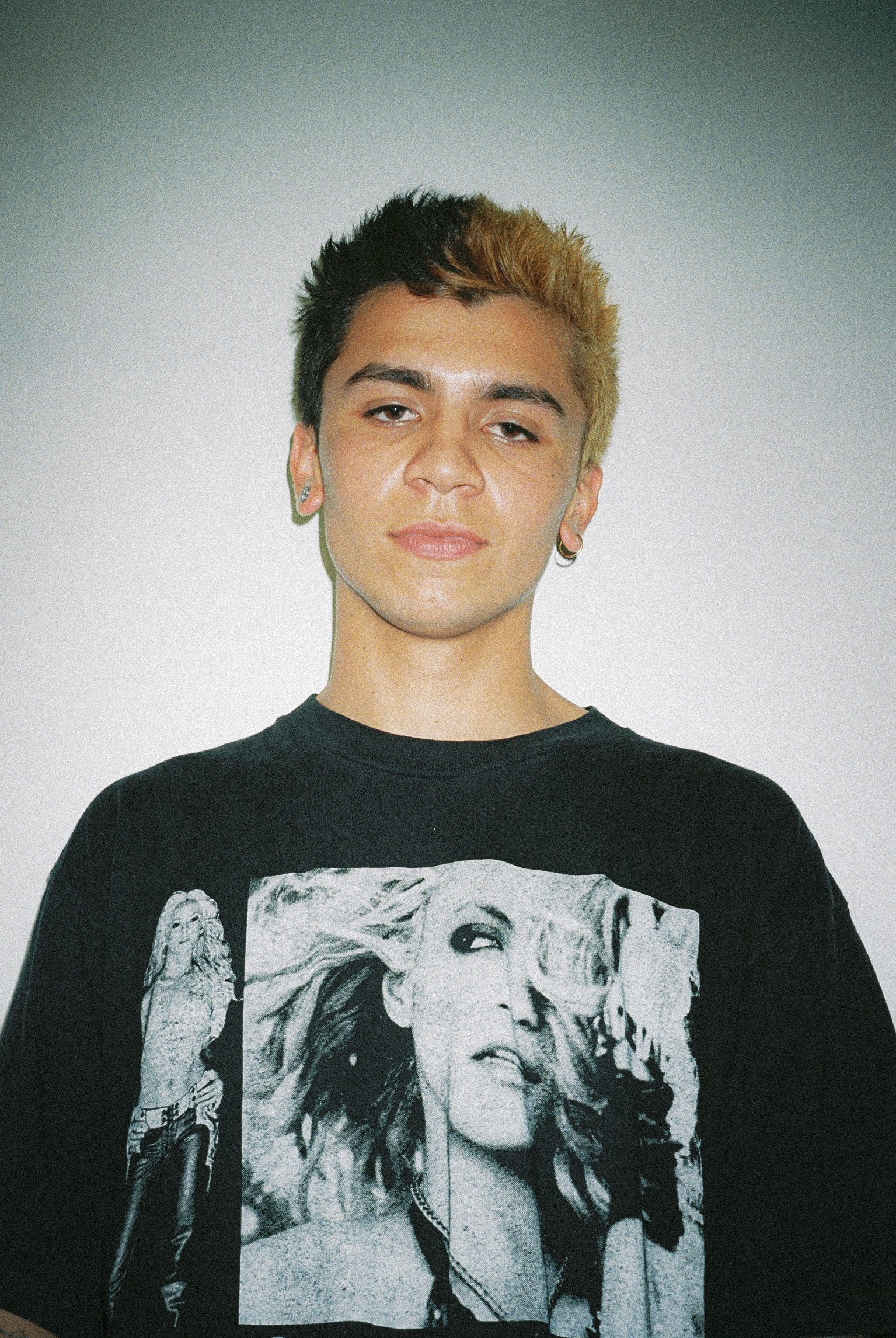

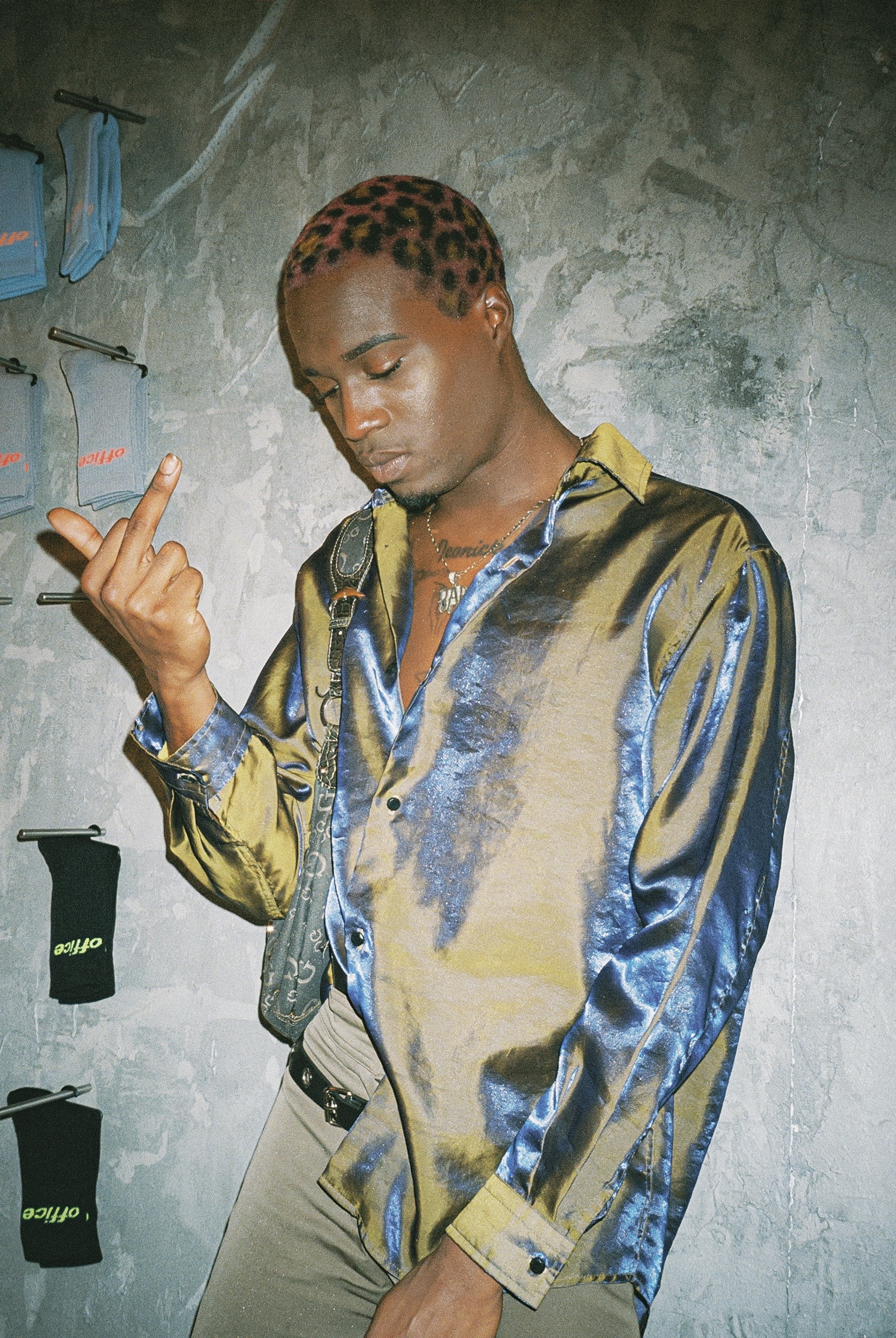

office: LA Edition

Check out some photos from the event below and come visit us on 424 Fairfax, LA—we'll be here for a while.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out some photos from the event below and come visit us on 424 Fairfax, LA—we'll be here for a while.

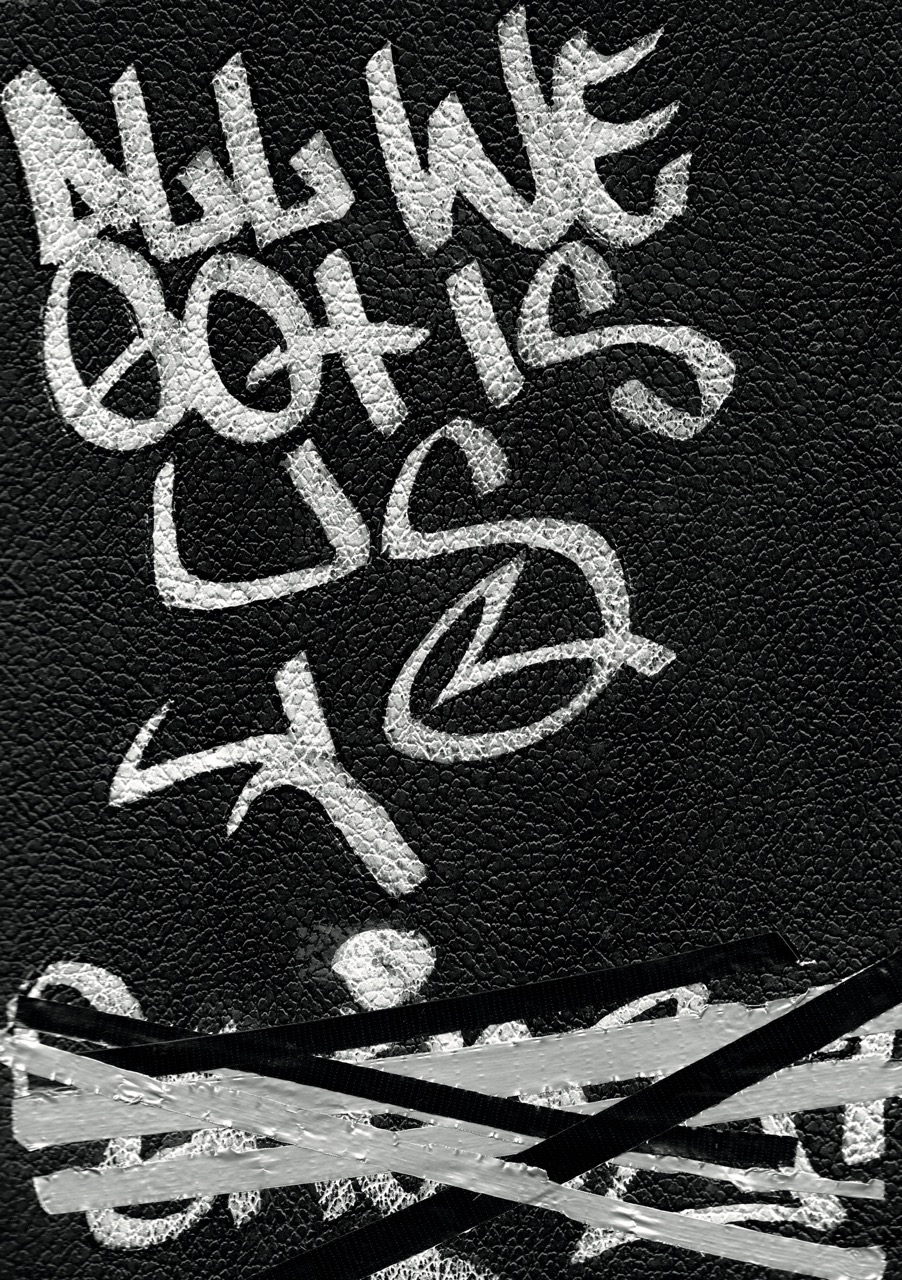

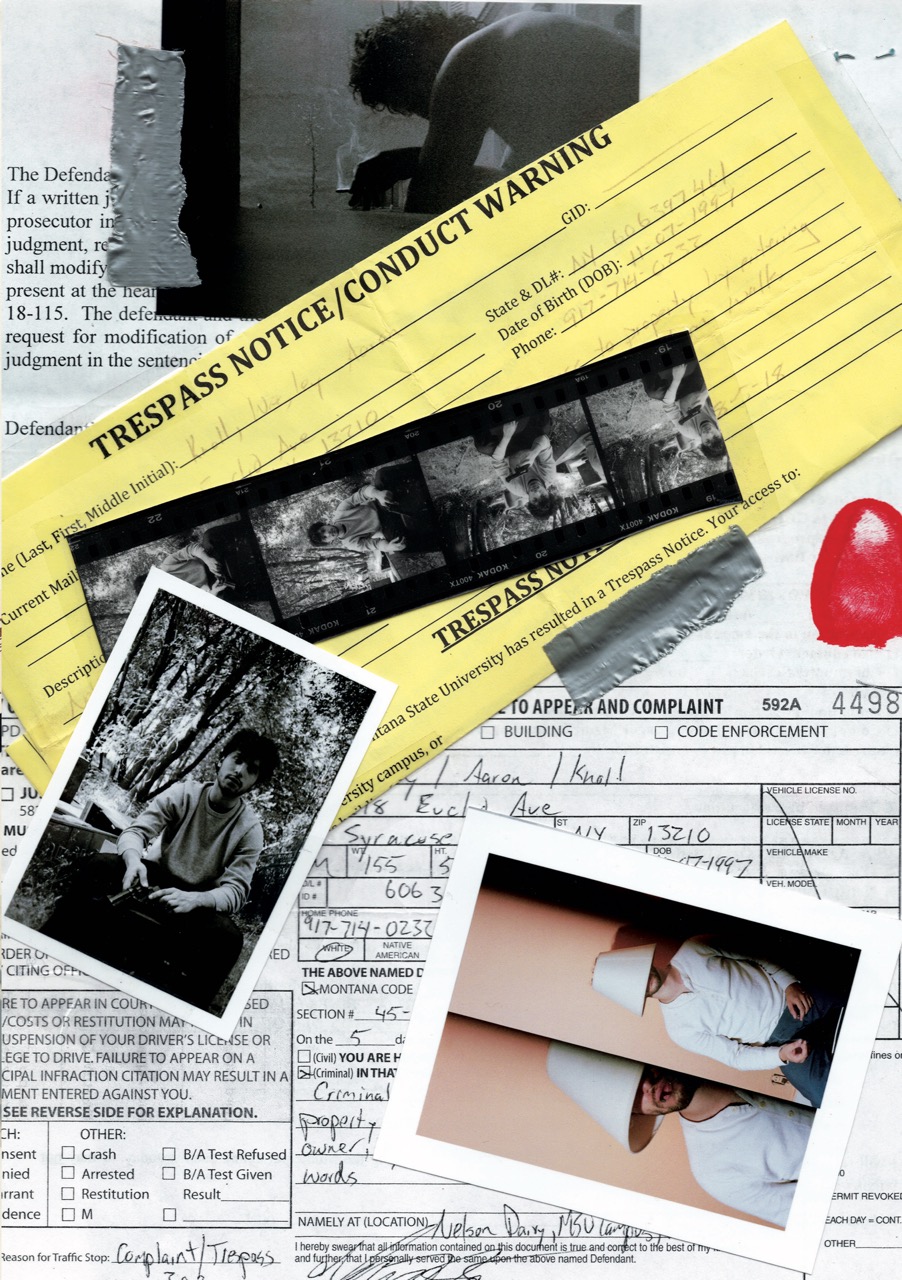

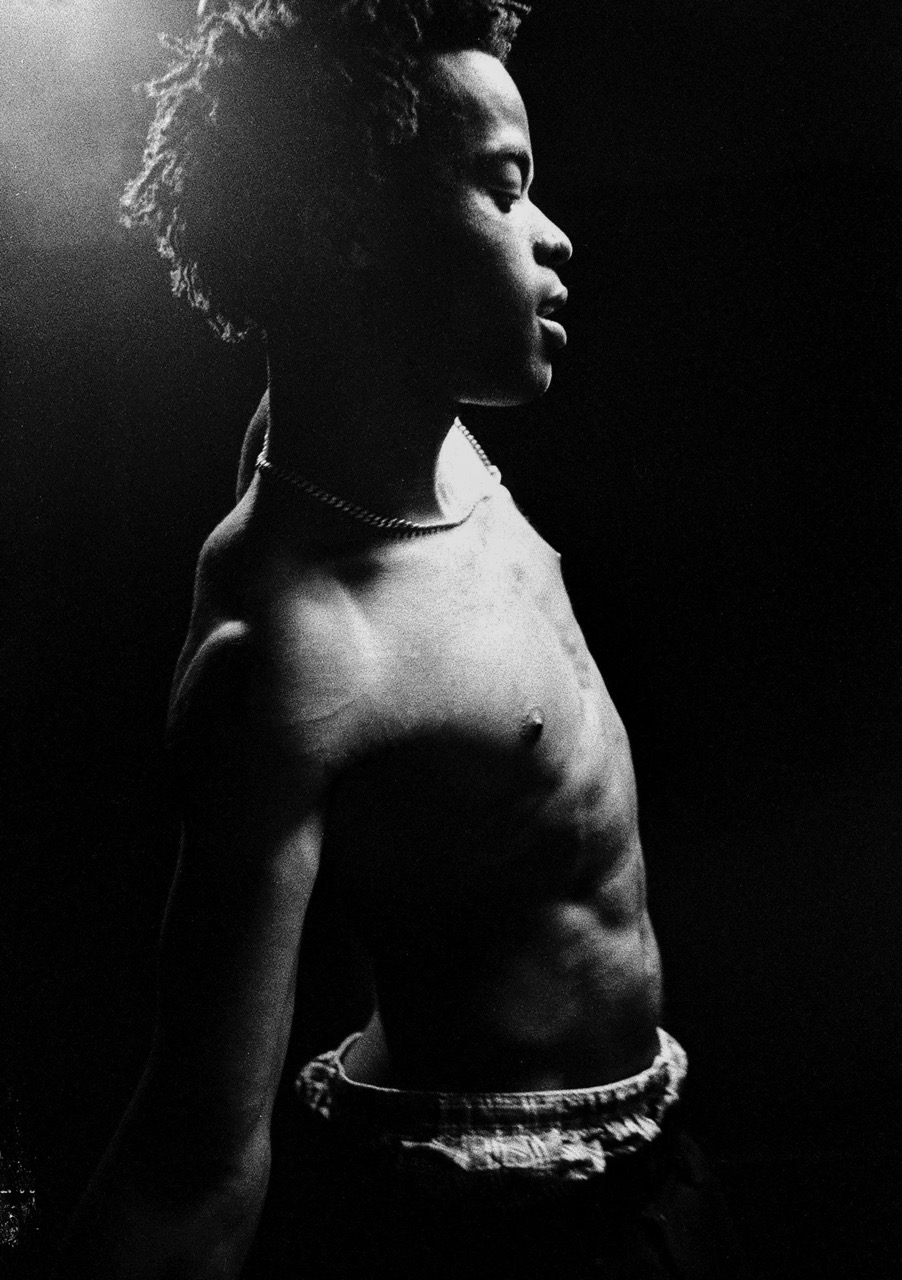

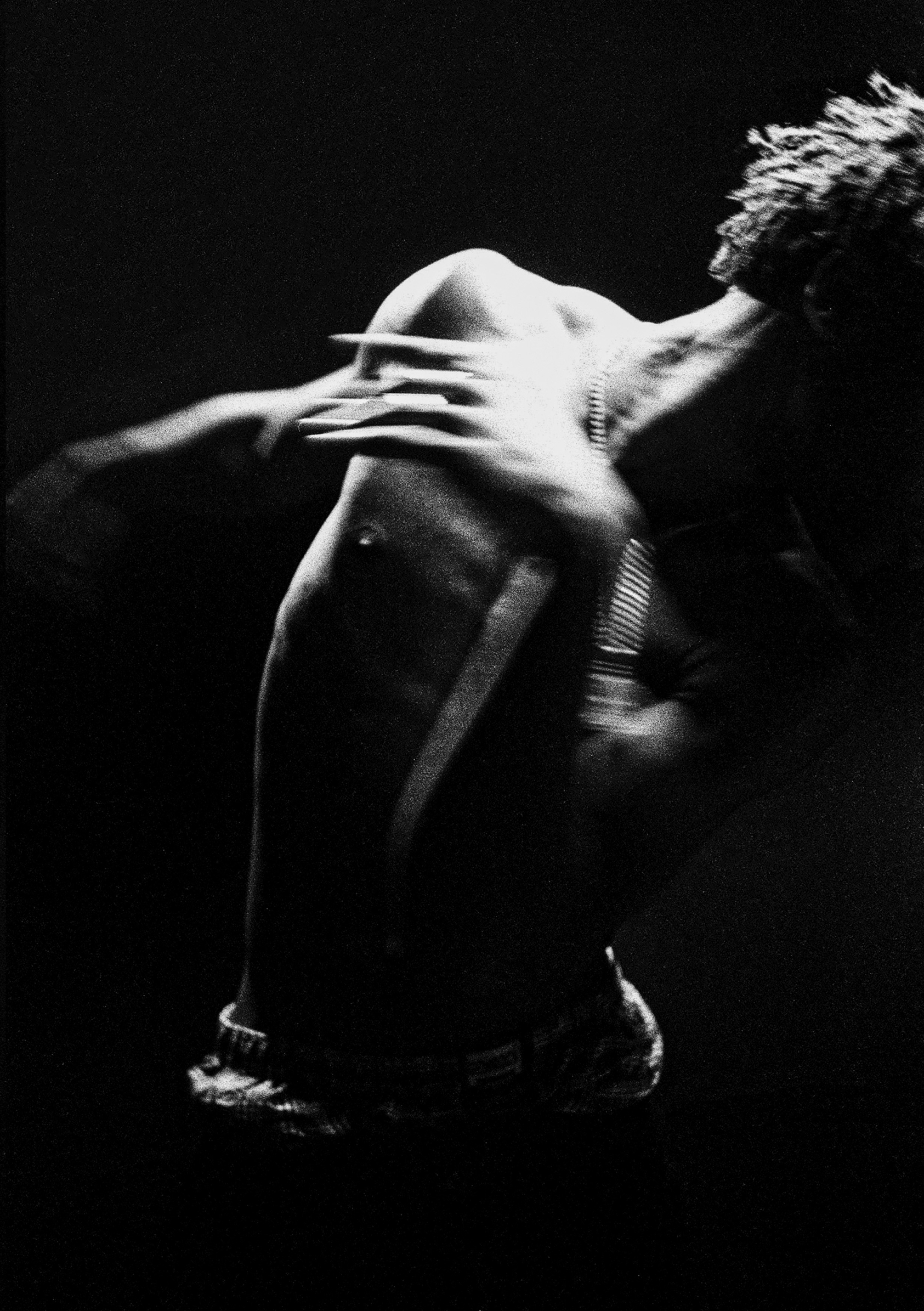

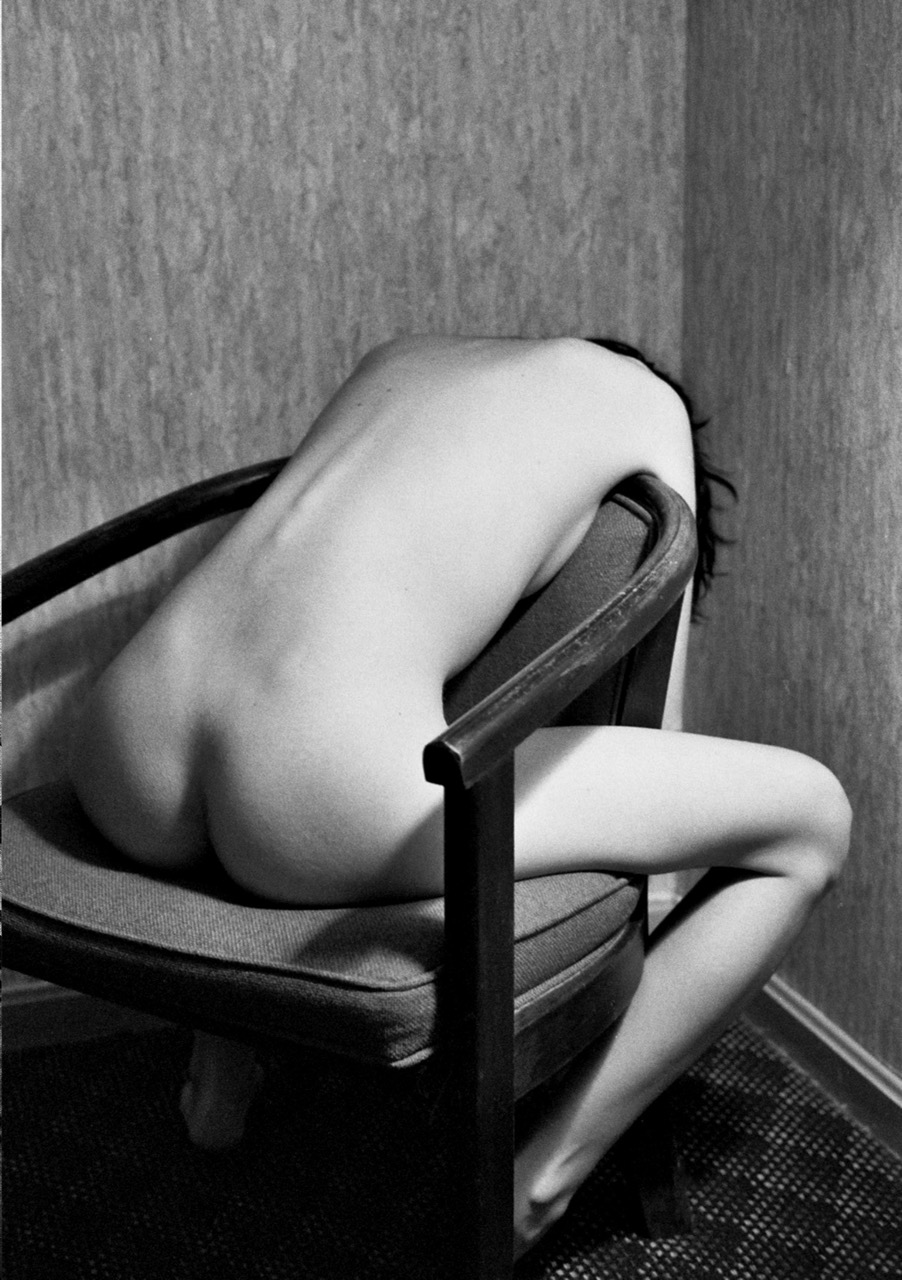

While these images expose prevalent themes of rebellion, his deep-rooted connection to the people and places he inhabits allows a blossomed sense of meaning. Instead of reveling in the past, he owns up to his faults with newfound introspection and a digested sense of his youth. Fading Smile is a love letter to the city he's always known, a place he could’ve left behind and sworn off. Instead, he preserves the past with tenderness and an understanding that although the city changes, his memories of it remain the same.

Hi Wes! Thank you so much for meeting with me today. Congrats on the release. How has 2024 been so far? Do you make resolutions?

Thank you! My new year was good. It was pretty chill. I relieved myself of the pressure to have a crazy night and celebrated with friends intimately at the house, toasted to the ball drop. I don’t really make resolutions anymore. In the past I have. A tradition of mine growing up was making a wish for the year and tying it to a balloon and letting it go into the sky.

I love that. So you grew up in New York. What is the biggest difference between the city you grew up in and the one you see now?

Yeah, born and raised. People and places have changed the most. There's less of a sense of community. The influx of people who relocated from other states has kind of eradicated the true identity of a New Yorker in their neighborhood. Besides lots of businesses falling victim to gentrification, the actual identity of a New Yorker has begun to take on a new definition, which is two-fold. I think it's a double-edged sword.

Do you think there will be a resurrection of the New York you grew up in?

I think it’s gone and it’s not coming back. I think there is this trend of New Yorkers, or people who grew up here, always talking to the younger generation saying, "It was great until the moment you got here. You just missed it." I think there is an element of everyone identifying with a late-to-the-party ethos. I do think we are moving in a different direction in terms of accessibility when it comes to living, the price of everything has become astronomical and it’s fostering less of an artistic environment for people.

Have you ever thought about moving?

I’ve thought about it, but it’s my bread and butter.

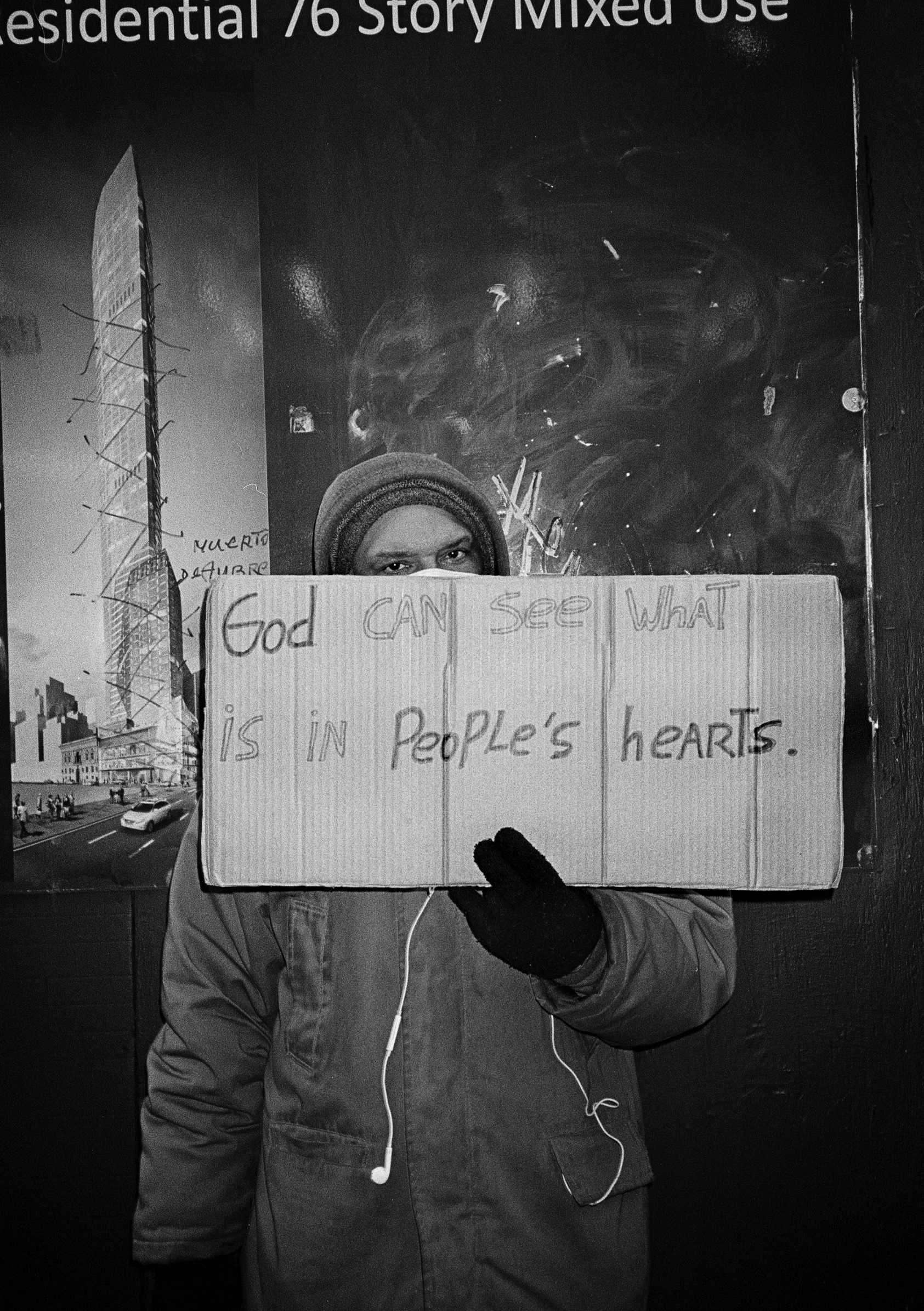

What type of person do you gravitate toward?

The freaks of nature. I think people who are unique individuals and don’t really give a fuck about what other people think about them. Also people who are just going to swim against the stream of normality and society. Whether it be their clothing or whatever they are ranting about on the street corner. Or whatever it is they choose to do with their life be it graffiti, panhandling, racking. I love to see the quirks within the human condition and give light to them, rather than step on those cracks in the sidewalk which I think a lot of people do without realizing.

Getting into the book, I was very drawn to the introduction. Can you expand on your process of writing it and what you wanted to convey?

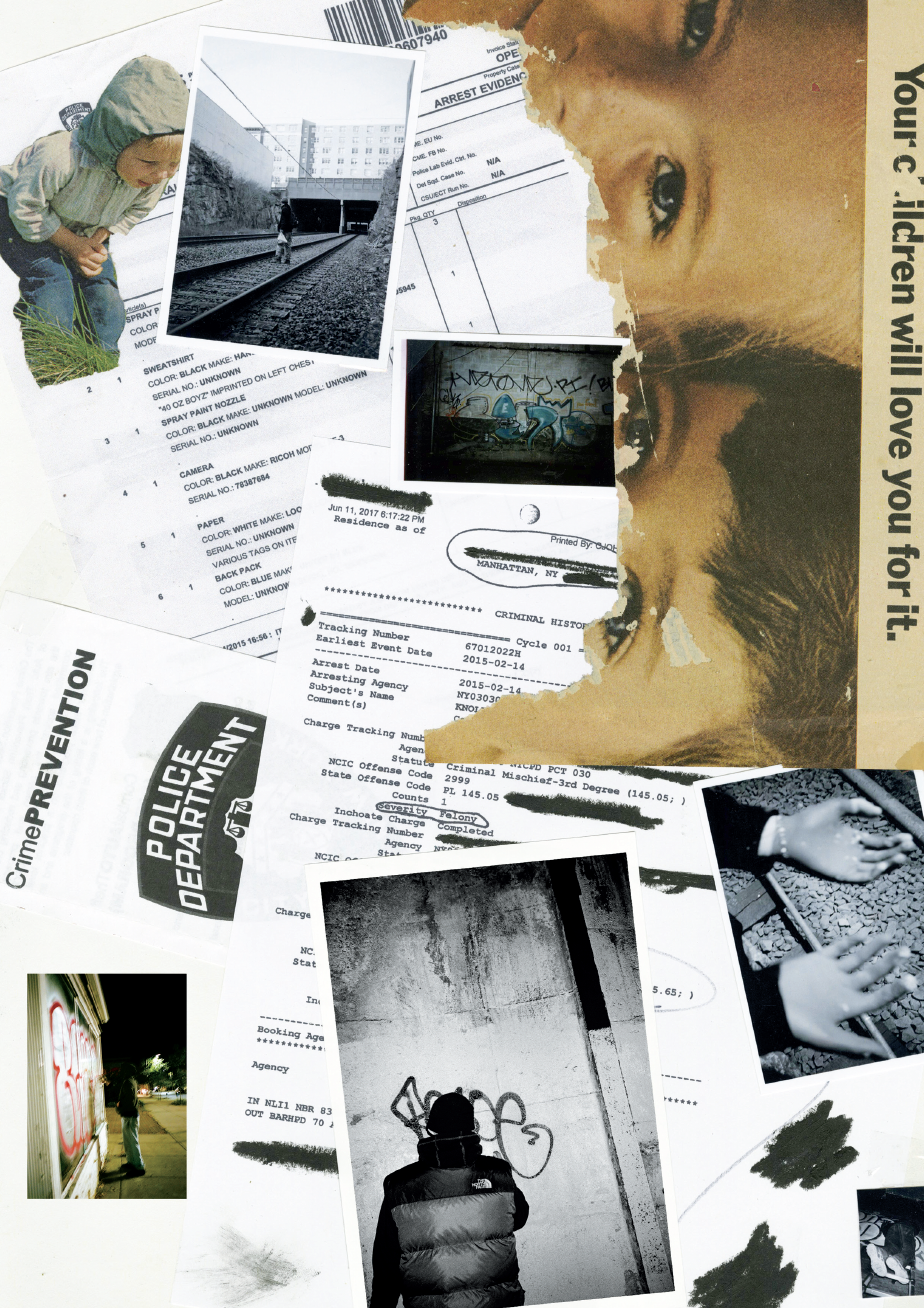

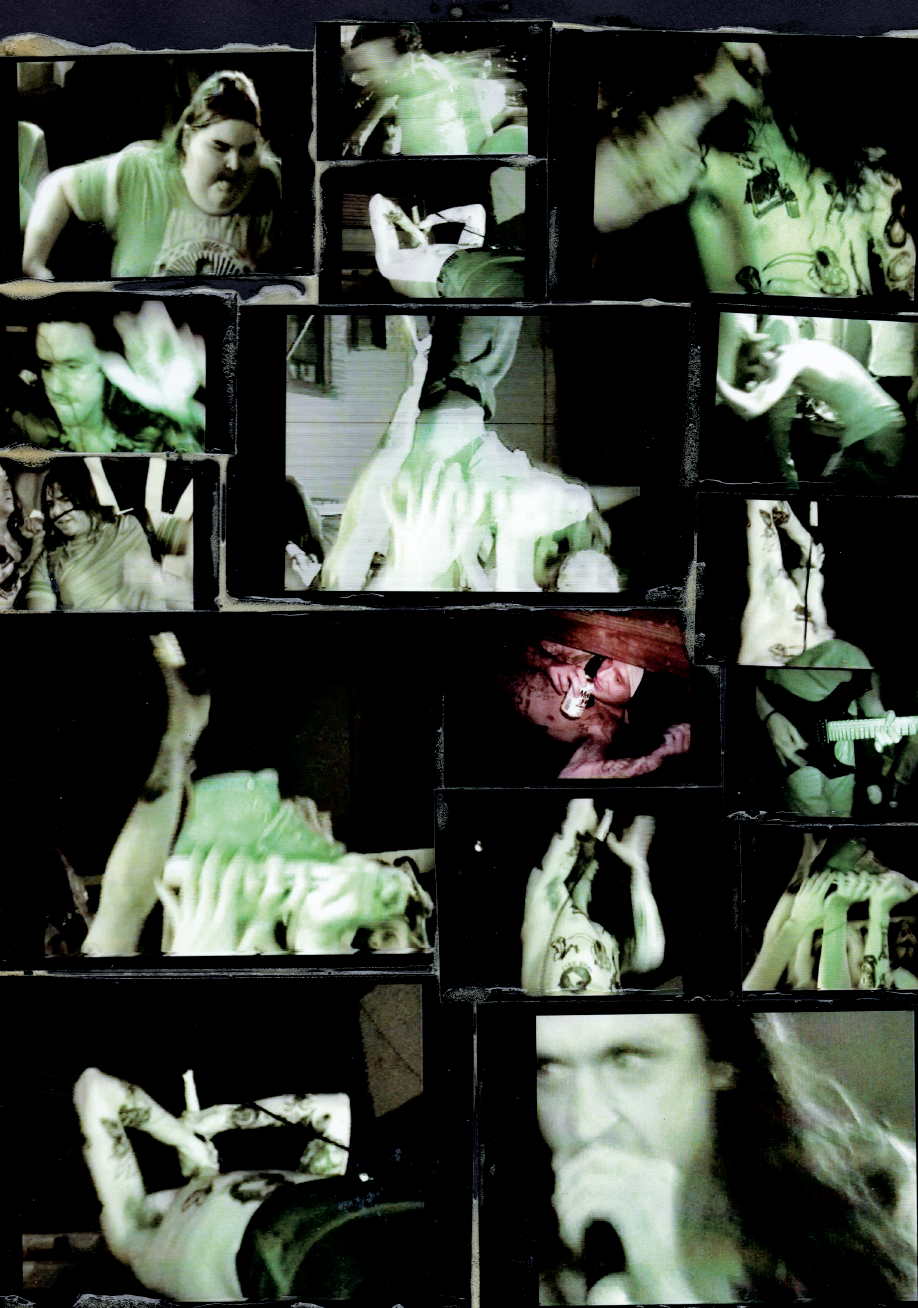

The introduction went through countless edits to capture years of unique stories as well as personalities. More so what this unique microcosm was to me. What I wanted to convey the most was this world I found myself immersed in, was representative of what I believed to be the truth and a right of passage for many New Yorkers, as well as many teenagers in general, regardless if they grow up in a major city or not. I don’t think people realize it is super universal, in all these oddly niche experiences and personalities, we have to keep it secret because we’re young. Something I wanted to highlight was the risk factor and what these crazy characters were immersed in… to just capture that cinematic level of disbelief from the stories that make up these images.

How much of your youth informed your stylistic choices?

Pretty heavy. I saw a quote once, that you listen to the music that you love when you're 18 for the rest of your life and I find myself falling victim to that. I find myself having a foot both in the past and the present. As I get older I begin to question that. And stray while trying to find out which is the right truth to follow. In terms of inspirations, art practices, or life choices, I have a heavy sense of identity from my youth and the way that I viewed the world then with a certain purity I hope to maintain as I age.

How did you decide to arrange the photographs?

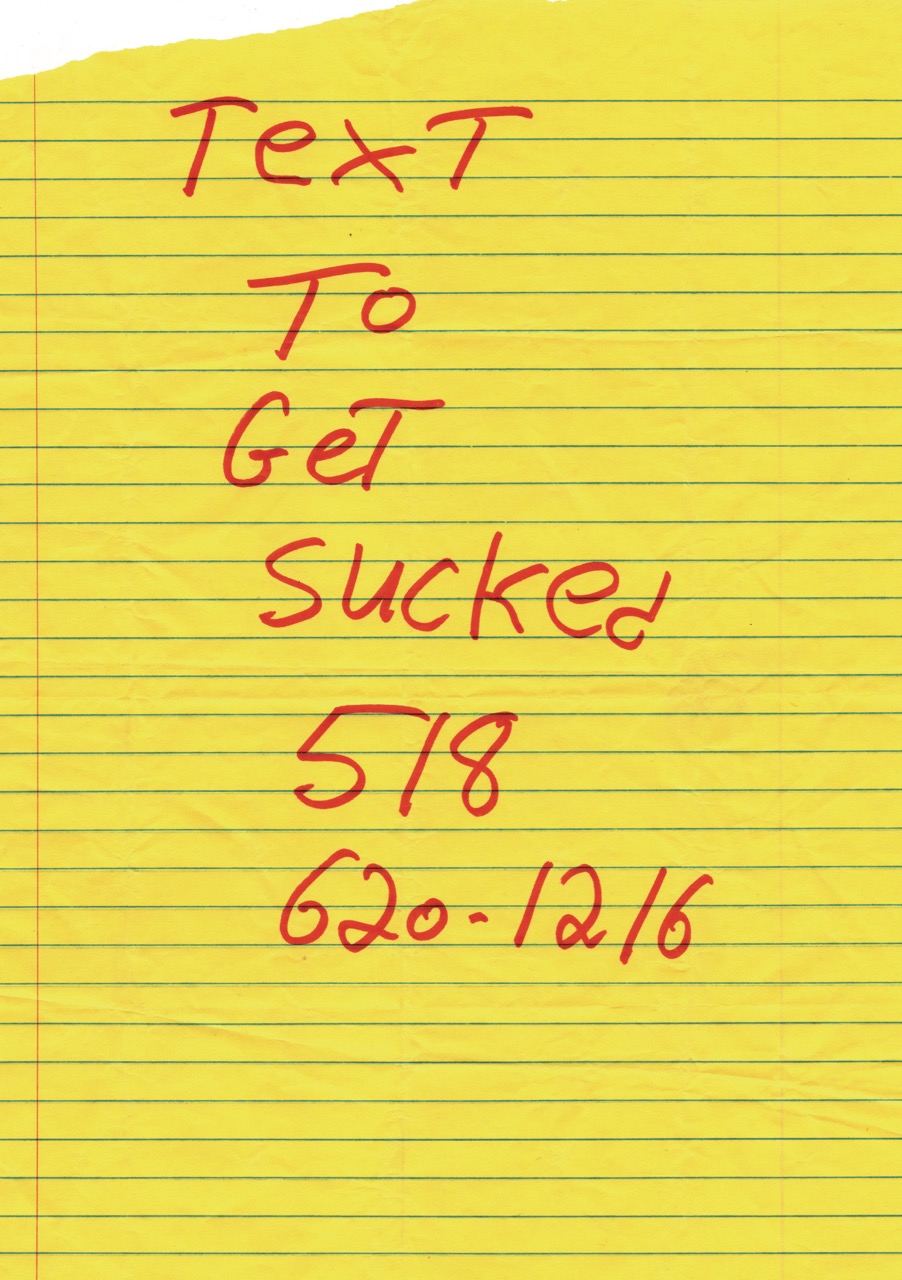

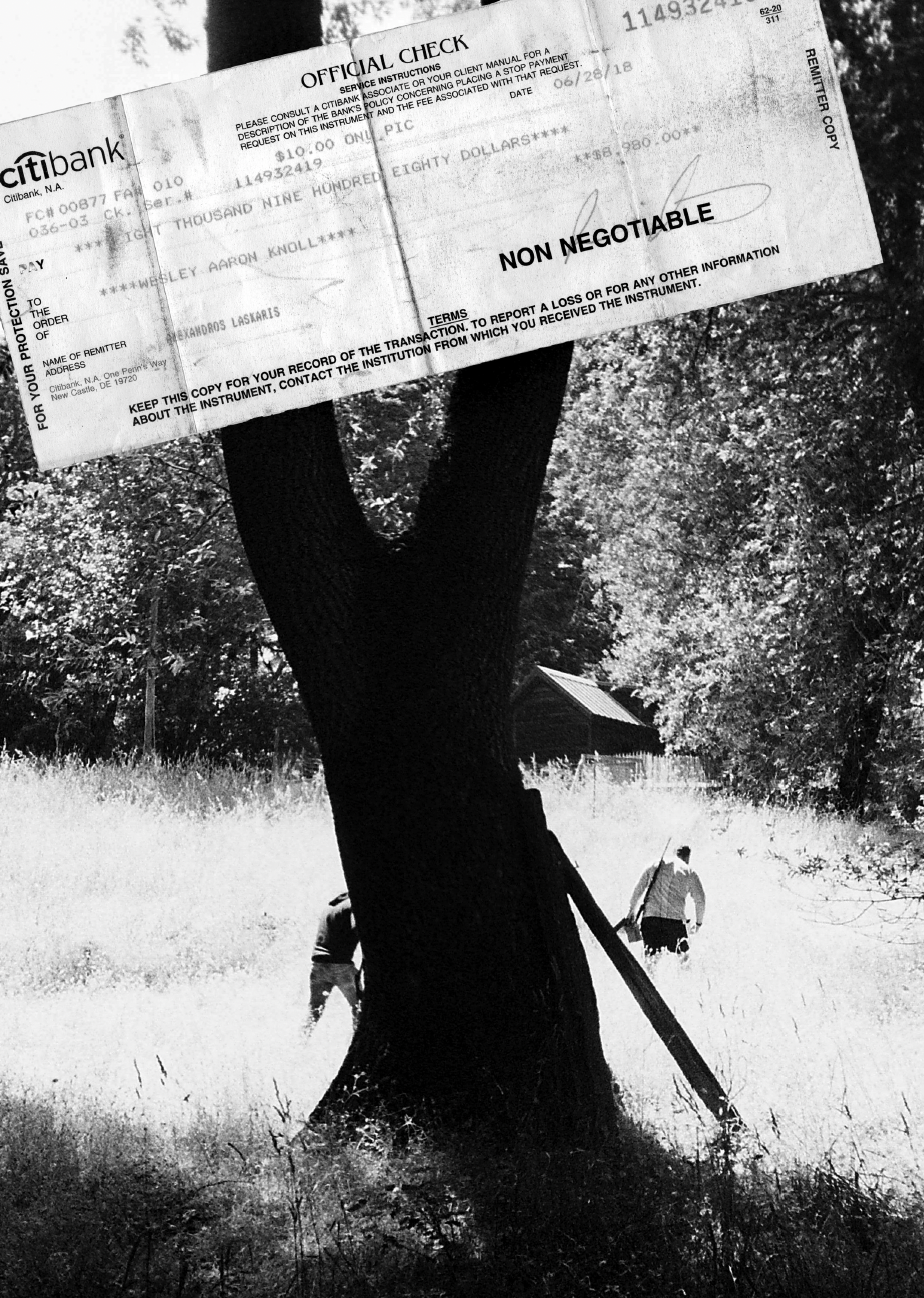

There is a narrative in terms of their sequencing. The order I was seeking was the first spread of the book: people climbing the sides of the highway to paint graffiti, following them climbing to this abandoned area, going off to explore the world, immediately getting arrested afterwards on the side of the road. Countless spread of journal entries of what's coming next. As well as what fueled and funded what came next, which is pounds and pounds of weed, ounces of coke, thousands of dollars. Then you are hit with a myriad of collages of the characters in the book who are living their lives, and exploring thematic ideas like someone who has a tattoo of loyalty across their neck; money laundering; people sticking their heads out the side of windows on road trips; girls kissing each other on prom night; or a letter I wrote when I was child after I stole something from a museum. My dad made me write a thousand times on a piece of paper: I will listen to my parents, I’m sorry for what I did. Towards the end there's a road trip chapter, I feel like once you spend enough time in New York you need to get out. There’s also a graffiti section, and one of going out to California to cop drugs and bring them back. The characters find themselves back in the city with love letters and death once again. It's an enigmatic look at that process, without revealing too much.

Anyone get upset about something you put in the book?

So far no or at least no one has confronted me. But there are definitely tons of things I did not include for those reasons as well. I think there is a level of intimacy that I definitely wanted to respect for certain people’s lives, narratives, and stories.

How did it feel releasing something so vulnerable?

The book has gone through so many iterations. I’ve worked on it for three years. I was really nervous leading up to the release because it has a ton of myself in it as well as other people. To me the greatest works of art are the most vulnerable, the most honest, and self-reflexive. I felt I really needed to put all of myself in it in order for it to resonate with people. So having done that and receiving such a positive embrace from friends and supporters was more than I could have ever imagined and feel grateful for.

Do you have a favorite moment in time during the book?

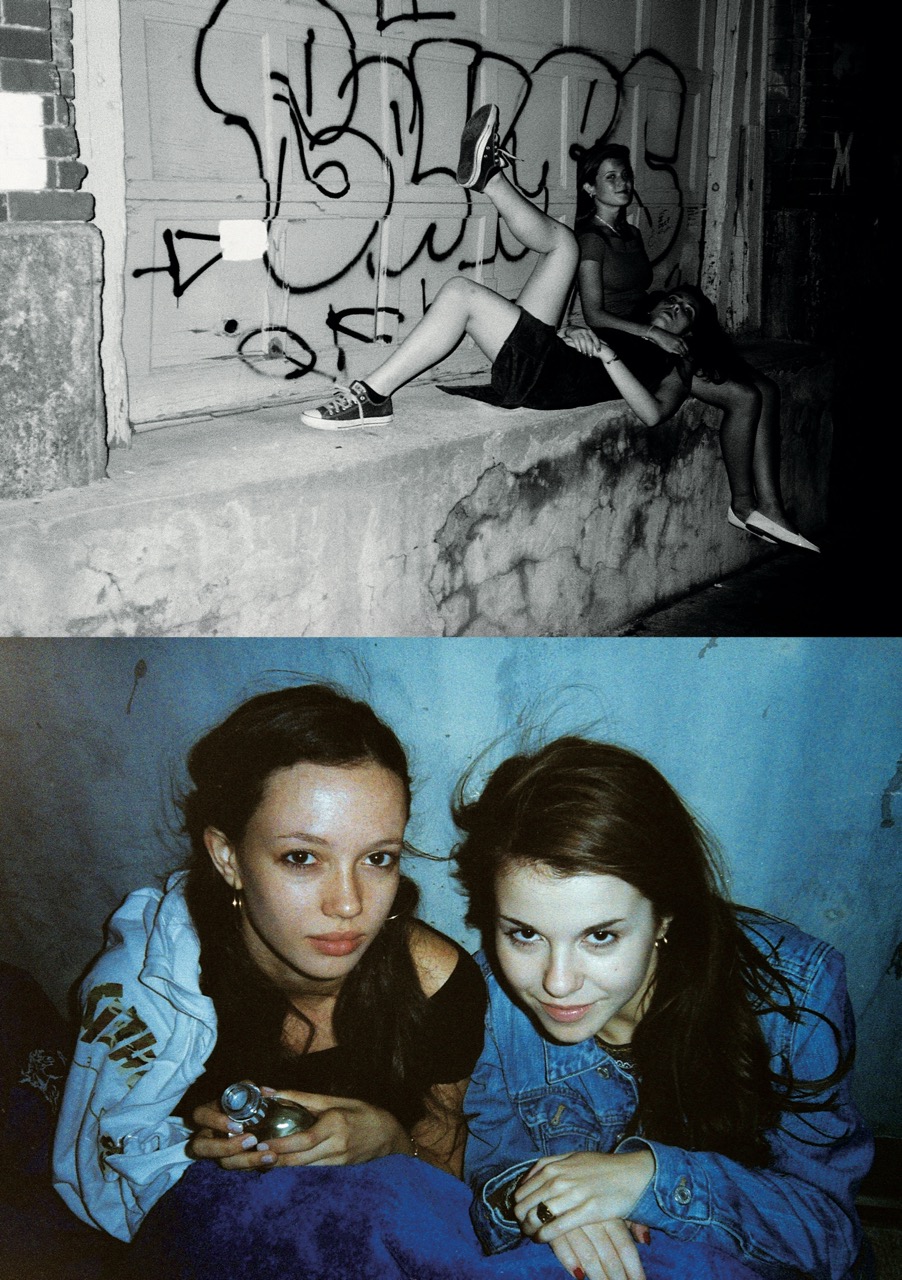

My favorite moment in time in the book... that's tough, but I would probably have to say either the photograph of the two girls making out, which was taken on another high school’s prom night or making it through TSA with over $50,000.00 in cash divided up between 4 carry-on pieces of luggage that we used to buy 100 pounds of weed. There's also a photo of a ripped sheet of paper from a yellow legal pad with the words “text to get sucked 578-620-1216” written in red ink which was thrown at me out of a car window one night while I was writing graffiti in Brooklyn after midnight. The other moment in time is one that is seemingly mundane, but represents the moments I cherish most from this time period: a photo of my two friends, Diego & Jesse, as we sat on this rooftop above 72nd and broadway, which became a very meaningful and symbolic place for this community of kids.

Is there anything you wish you could tell your younger self from that period of time when things were unstable?

Honestly, no. I don’t wish I had any other wisdom than I had at the time. I’d want my younger self to tell my current self to keep getting out there. Back then when I would make a decision about whether I needed to go out to document or experience or partake, I would ask myself if I would remember the evening I was engrossed in at home better than if I submit myself to the possibility of the unknown. I would turn my mind off like a light switch and that's something I would want to tell myself more today. Just go, don’t think, let my feet take me, and the rest will work out.

Do you ever wish you could go back?

I used to wish that I could go back constantly. When I left the city for college, I would listen to all the voice memos that I had recorded in attempts to transcribe dialogue and stories for the project, reliving the memories and laughing like a madman to myself. This was when the first true iteration of this project was made, back in 2017. The title I had then was "Qasim." Now I do not wish to go back, I think releasing this project has been carthartic, allowing me to understand, make sense of and close this chapter of my life — something I aimed to help other people do with their adolescence as well. A universality through the intimate.

Do you agree it’s fun until it isn’t?

No, I don’t agree that it’s fun until it isn’t. It is always fun. My mother always used to say a similar phrase in a told-you-so type of way whenever we would goof off too hard and injure ourselves growing up saying, “It's all fun and games until its not”. But, since time is non-linear, and we often fondly reminisce on moments in the past that seemed terrible, once over and behind us, they can be laughed at and reflected on with glee and acceptance. An old barber of mine from Sicily used to always say, “-but, ehhhwhaddaryougonnadoaboudit”. The best stories are always the worst ones. Sometimes we forget that until we realize it is rumination. Hindsight is 20/20.

Are there any other artistic mediums you’d like to try or are currently exploring?

I’m working on a short film featuring this lady I met on West 4th Street who's been living on the streets for quite some time now. Her name is Marianne. She has a beautiful singing voice and was a singer in her younger years. I’m looking to do more short films that are character profiles. Shining light on people who make the city run that I think don’t get a lot of shine, but who actually define the city.

What are you looking forward to in the future?

More adventures, more exploration, more stories, meeting more people and getting to understand them. I hope I can better understand myself too and help other people do the same.

Jupiter was born out of the conversations that Bacon and Harper had at that very first dinner, though neither of them knew it at the time. They commiserated about their jobs and the constraints that had been placed on their writing; “breakneck timelines” from editors that discouraged formal experimentation had drained their work of its pleasure and hindered its potential. They bonded over their shared childhood dreams of one day working as magazine editors. A few days afterwards, the conversation hadn’t left either of their minds. So the two women decided to write a manifesto, figuring that other writers must be encountering similar tensions in their practices.

“Something that we say often, that might sound hyperbolic but I think is really true, is that writers are an endangered species. Writers are going extinct in this very, very distinct way,” Bacon says. “I use that language because I think to speak of extinction is also to speak of a broader ecosystem that is deficient, that does not hold the things that we need it to in order to really do our work.” They continued developing their manifesto, meeting over Zoom after Bacon returned home to Chicago, and decided to add a micro-grant component to help support writers. By the next time Bacon visited New York and met with Harper in person in April 2023, the bigger picture had clarified: they were creating a magazine.

“It was like the sun broke through the clouds and streamed into the coffee shop. Our meeting allowed us to realize that we needed to create the publication that we wish we could have written for, become the editors in chief that we wish we could have been supported by,” Bacon describes, referencing Toni Morrison. “It's really fueled by this shared philosophy around the importance of writing, of course, but also the conditions that we need to deeply enjoy it. Can we create ecstatic editorial conditions? is the thesis we’ve charted forth on.”

Bacon and Harper share a steadfast belief in the importance of art writing and the art critic at their best as belonging to the ecosystem of creation; in other words, part and parcel of the art itself, not separate from it. A good piece of art writing can facilitate an audience’s connection with a work, and excavate further meaning from it, even for the artist themselves. “The art of criticism itself is rooted in care, and can be viewed as an act of care and can be really practiced as a tool and a method towards deepening and lengthening not just our lines of inquiry, but also ultimately the ways that we understand ourselves and each other better,” Harper says. “I've been really astounded to learn the different ways that I can discover more about myself, about my loved ones and the people around me through really deep and spiritually led excavation around art, around art making processes.”

“But when we think about the way that the world is currently set up right now — care cannot be a cliche. It has to be a mandate,” Bacon adds. “And I think having this willingness to really grapple with art objects that challenge me conceptually, aesthetically, emotionally, spiritually is a way of answering to that mandate of care at the moment.” That process requires time, and providing writers with that time is one of Jupiter’s core intentions; Bacon and Harper know that in order to live alongside a work or art object for long enough, writers need proper compensation and more generous deadlines.

The magazine’s name came to them later down the line, after they had already first announced their joint venture at a panel event in Chicago. Bacon says she began waking up at night with “dispatches,” unable to return to sleep until she had written down the messages that popped up in her head. One night, the dispatch simply read jupiter. After some reflection, she and Harper fell in love with it as an “incantation,” one that promised a long prosperous life. Jupiter is the planet of expansion, abundance, and luck; it is also a gaseous liquid planet; it also rules over both Harper and Bacon’s astrological charts.

“It’s the one truest expression for what it is that we've been working towards building, which is ultimately something that has this air of malleability; it's elastic, it can stretch, it can bend, it's not pinned down in any one particular way,” Harper says. “And both of us are really deeply led by spirit, and allowing that to shine through with such clarity and vigor is something that's really important to us — within the art space, but also in general within editorial spaces or what might be considered a ‘professional space,’ these spaces ask us to silo off parts of ourselves in their corner. I think Jupiter felt like the perfect way to really assert who we are and be really loud about it.”

“Art criticism is seen as this extremely pretentious, extremely erudite, extremely curtained off discipline, and we're interested in bringing a degree of unruliness and waywardness into what that means. Criticism is happening all the time, we're just not calling it that,” Bacon adds. “And I think naming the publication after a planet rather than something that feels more legibly intellectual is really important to signal the way that we are also trying to bring a shift in who regards themselves as a critic and who reads criticism."

Read the inaugural digital issue of Jupiter Magazine here, featuring contributions by Akwaeke Emezi, J Wortham, Rianna Jade-Parker, Joshua Segun-Lean, and Diallo Simon-Ponte.

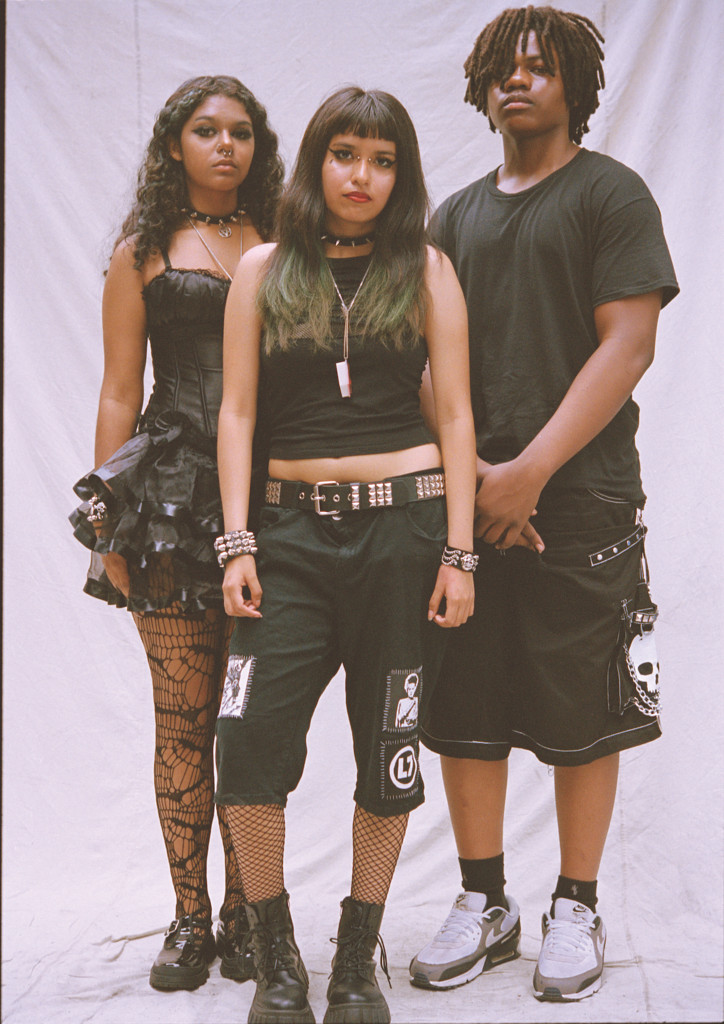

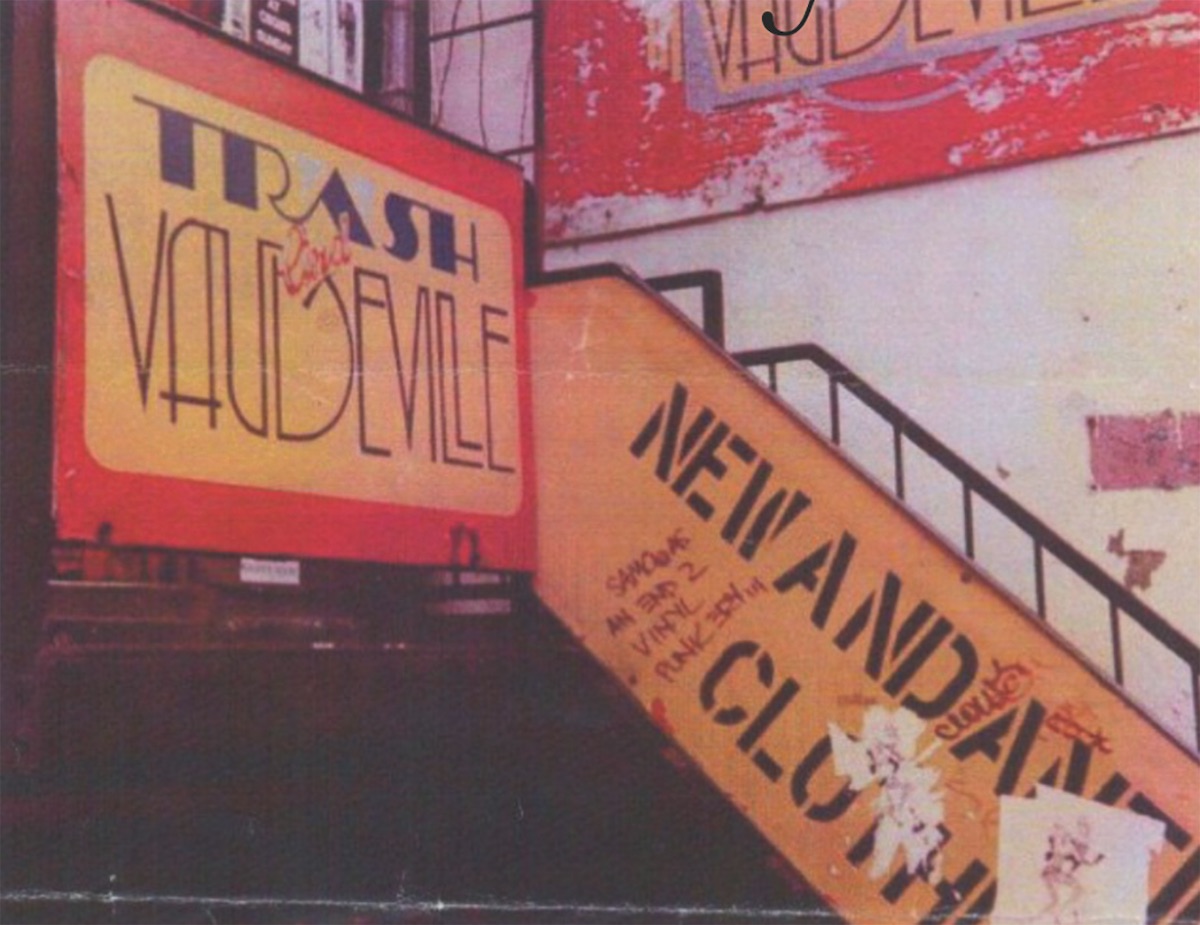

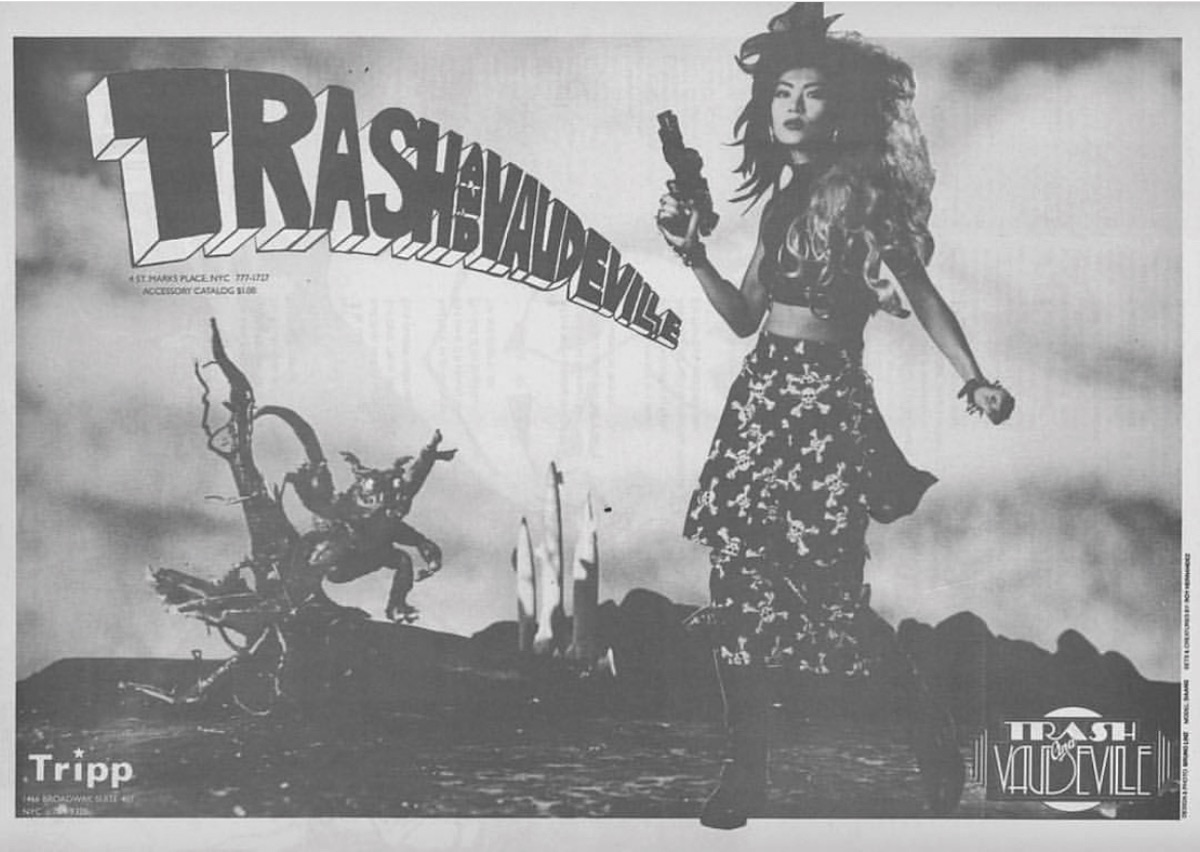

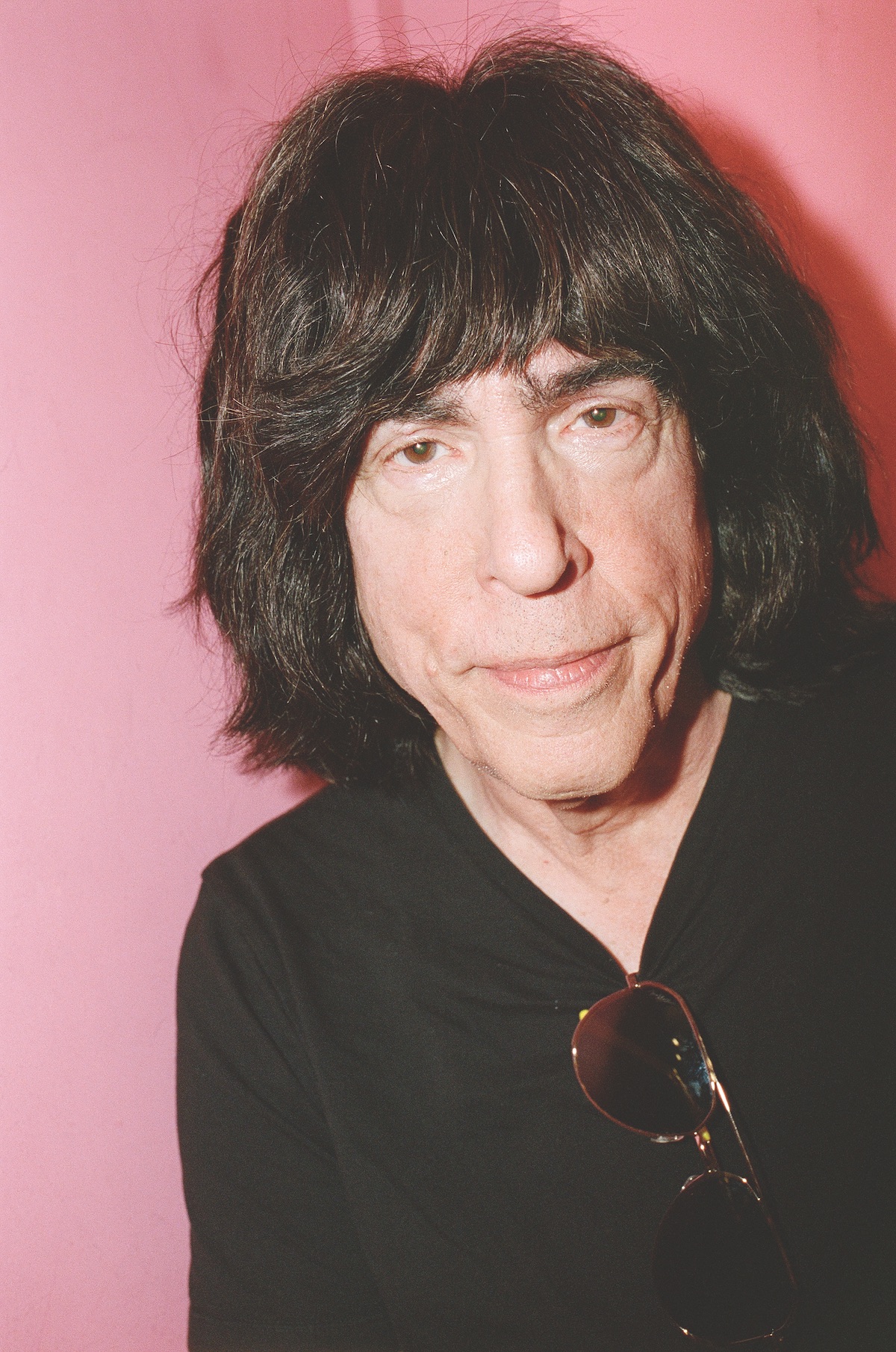

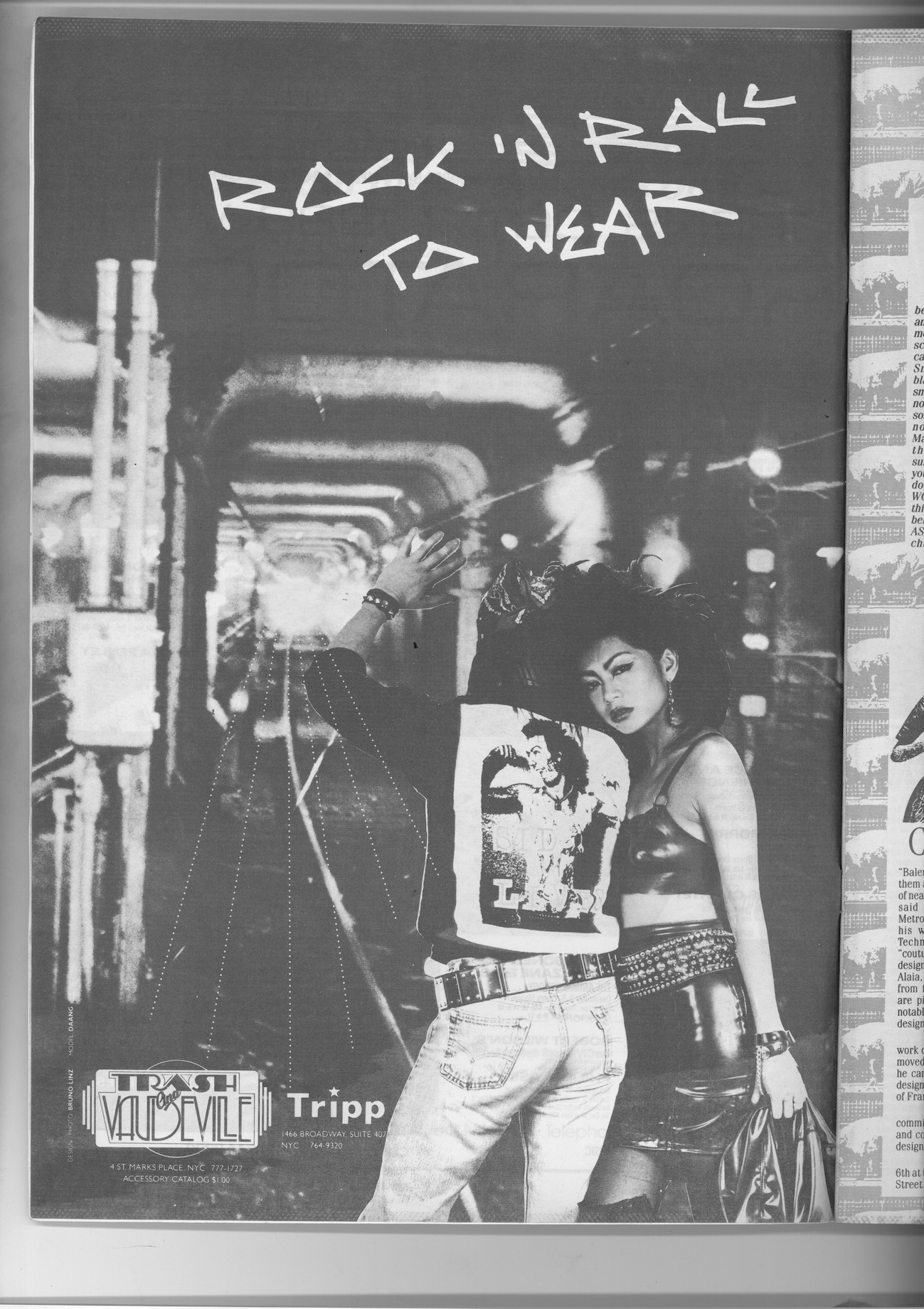

Over the decades Trash and Vaudeville has weathered cycles of cultural upheaval, economic instability, and waves of gentrification — the store eventually moved around the corner to East 7th Street in 2016, where they’re still going strong — with the support of the so-called “Trash family,” a faithful crew of multi-generational customers, colleagues, the occasional rock star, and eventually even some actual blood relatives. One of those rock stars, and a longtime friend, with his wife, of Ray and Daang’s, is Marky Ramone. Having drummed with the bands of punk pioneers like Jayne County and Richard Hell, in ‘78 Marky joined seminal punk quartet the Ramones, a band whose heavy-banged haircuts, biker jackets, and black jeans — provided by, who else, Trash and Vaudeville — were nearly as genre-defining as their amped up power chords and blunt, disaffected lyrics. So who better than Marky to join Ray and Daang to discuss the overlapping worlds of music and style, and the near fifty-year reign of the landmark shop that serves them both.

[Originally published in office magazine Issue 20, Fall-Winter 2023. Order your copy here.]

SKYLIN, 14

FRIDA, 16

PRINCE, 14

We're here at Trash and Vaudeville, a shop with, God, almost a half century of history. It's fashion history; it's New York history; it's rock ‘n’ roll history; it's punk rock history, and we're here talking to Ray and Daang Goodman, proprietors and the spirit of the shop. They've been with it for the long haul. Also joining us is the great Marky Ramone, long time friend of these two.

Marky Ramone— … and the other Ramones.

Yes, I’ve heard of them. [Laughs] So, welcome. I think we'll start at the beginning — or a beginning, at least. When you hear about New York in the mid-seventies it's a city on the brink. The city is going broke, there's crime skyrocketing, and unemployment. It was '75 when you opened Trash and Vaudeville. What was it like opening a shop in that environment? Did the shop play off of, or reflect that feeling in the city?

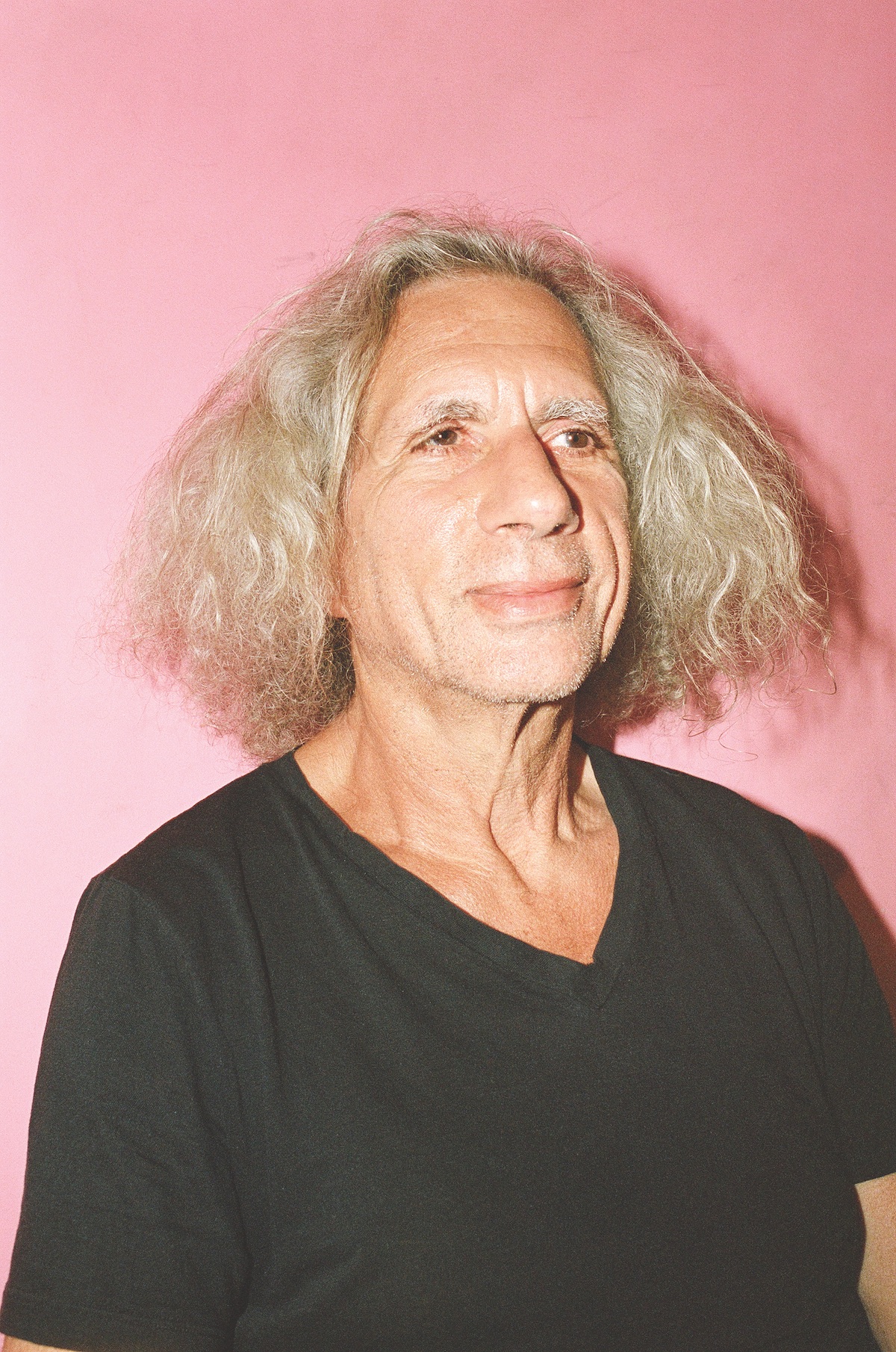

Ray Goodman— You know, I had just myself moved into the city. I was 21 years old. I really wasn't thinking of it in those terms at all. To be honest, I was just so happy to be there. I had been going to St. Mark’s for quite some time, and I guess being the age I was, I just never really looked at in terms of what was going on around me as far as the economic situation and the crime, I was more concerned with the music, what bands we were going to see, and things like that, you know? All the positive stuff that was going on.

And where were you arriving from, Jersey City?

RG— I grew up in Jersey City. Actually, my mother brought me to St. Mark’s for the first time when I was 13 to see an off-Broadway play down there, and I just remember getting out of the PATH train, walking down 8th Street, and when we got to the corner of St Mark’s and Third, looking around and saying, I don’t know what’s going on around here, but I just felt right. And that was it. I started coming on a regular basis. I just love it.

MP— So Marky, around that time was the shop part of your stomping grounds yet?

MR— This was the store. This was the store for everybody. All of the bands that played CBGBs and everybody hanging out in the city, you know, this was the look and it still is.

Did you get a sense of the challenges the city was going through at that time? Or were you like Ray, kind of in your own pocket of it and unaware of what was going on outside of that?

MR— Nothing changes, you know. It’s still the same stuff. The homeless, unemployment, the whole deal. But what did we do? We just formed bands and played to forget about that crazy stuff. We just put all of our energies into our work, and then CBGB started and the rest is history.

RG— The economic situation was tough and the neighborhood was going through a bit of a rough period, but that enabled me to rent the space at a price that seemed workable and realistic.

Did you pick up the space from a shop you were working at already?

RG— Yes, I had worked there for about a year and a half, stayed very good friends with the owners of the store that had previously been there, and let them know that if they ever needed me, I was around. And then one day, they all ended up retiring, the store was closing, and one of the partners offered me the opportunity to buy the space from him, which I did. I had been to London, and had this concept of a store that sold vintage and of course mixed in some new clothes. That was the concept we started with.

But you had a little bit of training in this as well. You had an education in merchandising from FIT. Did that help formulate the idea or was that just sort of a step along the way?

RG— I think it was more of a step. Don’t get me wrong. No, it was great. I shouldn’t say that. It was actually very important because that's how I got to go to London the first time. I got to do my practical work at an internship in London. So that did get me there, and that had a lot to do with my aesthetic and my style. So it had a lot to do with the aesthetic and my style, but my concept not so much. I went to FIT to appease my parents and to get a formal education, but I think I learned more in the year and a half that I worked at the store.

Now in the ‘70s Daang, what were you up to? Had you made it to New York yet?

DG— [Laughs] I was in Laos at the time.

And what brought you over to New York, or — it was California first, wasn't it?

DG— Laos fell in ‘75 so my family moved to Thailand, and I went to San Francisco for college in the ‘80s.

[Laughs] When did you first set eyes on this insane man over here?

DG— I think we met in New York. We were doing a trade show, like a boutique show.

RG— You know, we met at the show then we started this long distance situation. She was living in LA at the time, but there were lots of trade shows back then. You could almost be on the circuit, traveling every other month to some place for some show. Once our paths crossed, I would go to LA and she would come to New York and finally, when we realized that we wanted to spend time together, seriously, I asked her to move to New York and then went out and bought the ticket.

And you two connected on the two things that make Trash and Vaudeville what it is, fashion and music?

RG— Right, the thing is that my mind was blown when I first met Daang and picked up on her extensive knowledge of rock and roll. She knew so much, and that was one of the things that really impressed me and I realized that that's just how she was. She is very smart and she has that ability to come into a completely strange situation or environment and study it, learn it, master it, and then control it almost — in a positive way. And that was great.

DG— After we met, we always tried to make each other's dream come true.

That's very sweet. Marky, that’s why we sat you between these two. So they could flirt over you.

RG— [Laughter]

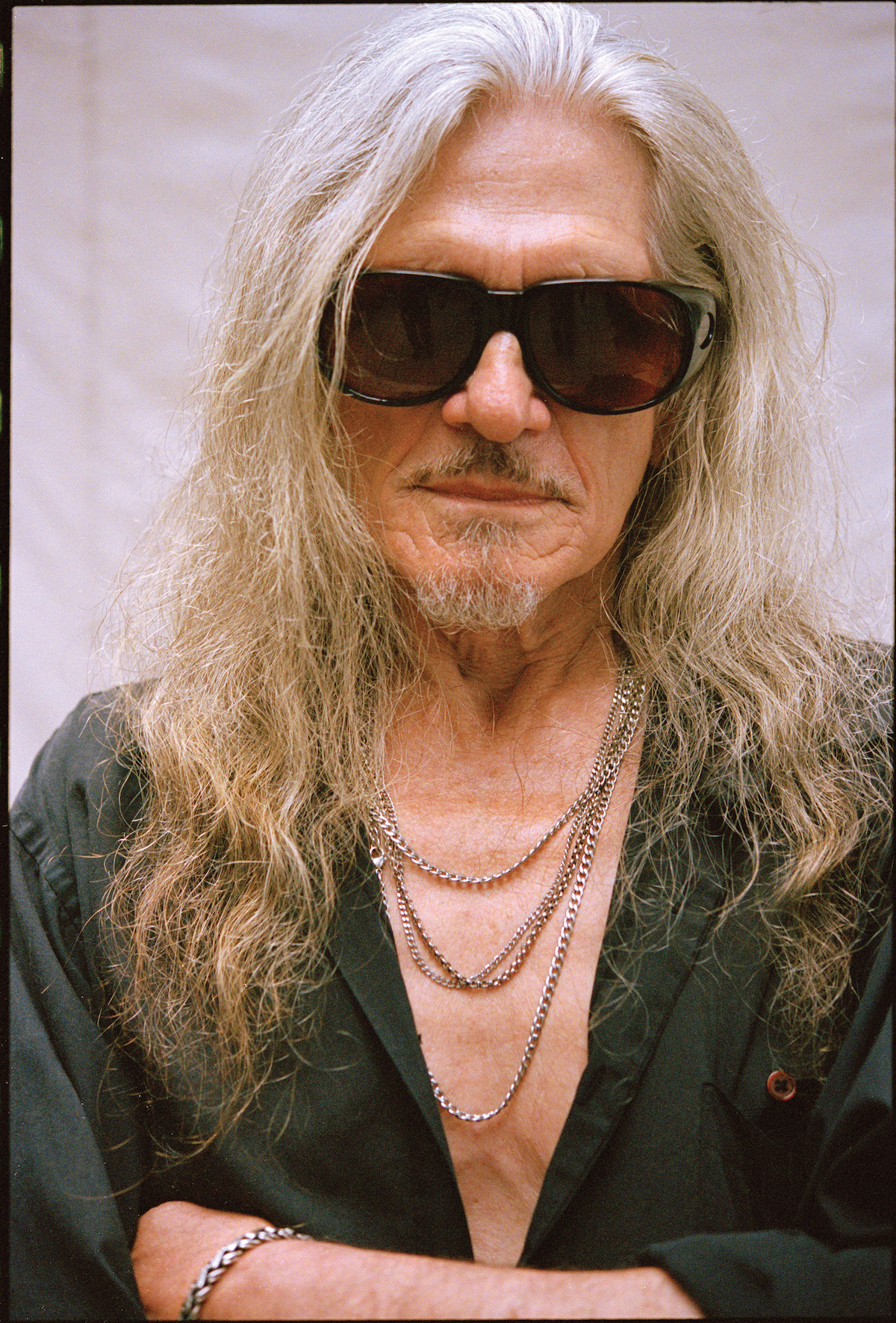

DAANG GOODMAN

Ray, it also sounds like you had some musical aspirations early in life, and it was drumming that you had your heart set on, right? And then we´ve got a successful drummer here — is there a little bit of living vicariously through Marky?

RG— Yeah, absolutely. I mean, obviously I realized early on that drumming was not gonna happen for me. I had friends and people I grew up with like Clem Burke, the drummer from Blondie, that were doing it. But it wasn’t for me. My whole idea was to stay close to the scene so I figured if I’m not gonna do that, what are my options? At that point, I started doing some psychedelic lighting shows for a little bit, then I got into clothing and we started with selling rock and roll T-shirts and I figured that there was a shot in that. I liked working for that store. Basically being a groupie at heart, I loved the idea of creating this store that hopefully would attract those musicians and entertainment people I wanted to surround myself with.

Like Marky said, it was the store, it was the look, it was one of the nexuses. If you’re not at a show that night, then where are you going? This is one of the places that those people would flock to, which is great. You talk about the “Trash family” and it does sound like there's so much of that, just being in each other's orbits, and keeping the fashion and music scenes kind of overlapping.

DG— But with Marky it was different, it was family at first sight.

MR— I knew that we had something in common just looking at the clothing and the music and so we stuck together.

RG— We hit it off.

MR— My wife Marion is best friends with Daang.

Marky, tell me a little bit about how you first got into the New York music scene. I know you played in bands before joining up with the Ramones. First of all, how did you start drumming and what inspired you at that time?

MR— Oh, I was 12 years old? I saw the Beatles on TV, and I wanted to be Ringo Starr. As time progressed, I liked other drummers, and so I figured, let me start piecing together a drum set. So, the first band I was in was called Dust and we did two albums. And then I figured, you know, let me hang out in the city. So I started hanging out at Max's Kansas City. Then CBGBs opened and I went back and forth. Then I started playing with Jayne County — Wayne County — then I joined Richard Hell and the Voidoids making The Blank Generation album. And then Tommy Ramone, who was the Ramones’ first drummer, was leaving. He wanted to produce. So he and Dee Dee Ramone asked me to join the Ramones and I saw them at CBGBs. When I knew Tommy was gonna produce, I knew they were gonna get a good sound so, I stuck with it and that was it. And then I became Marky Ramone. You know, I just had to get used to it, but then everything went nice and smooth.

MARKY RAMONE, RAY GOODMAN

Was it much of a transition for you to take on that role and become Marky Ramone, and did fashion have a little bit to do with that?

MR— Well I grew up in Brooklyn, and I always wore a leather jacket you know, jeans and sneakers, so it was easy. You know, you don’t push it, you just get into it and let it ride. The next thing you know, people started getting familiar with me and it all worked, you know. I always say good things about Tommy. I always say good things about the other guys. I did 10 albums with them and did 1,700 shows, so something was right.

MP— Ray, these days so many celebrity musicians have a team of stylists and people to dress them and shop for them, and I’m sure plenty shop here. But I'm curious if you could speak to folks who have been friends of the shop or customers over the years that you felt really had their own personal style and something unique that nobody else was doing.

RG— First off, the Ramones. Going to see them live, going to their shows back then and even now when Marky's playing. It was perfect. They all had that look, they looked like a band and they looked like the music that they played. The Clash was a great band that had a look in mind. They would come in themselves, and were also very kind to the store, especially Mick Jones. Lots of people would come in.

Prince was a good customer to the store, he would come in on a regular basis. He'd pull up in his purple limo. I remember when the Cars first started coming in and they’d buy a T-shirt here and there, then they got signed and they went crazy. Patti Smith. Iggy Pop. Blondie, of course. The famous photographer Lynn Goldsmith brought Bob Dylan in one Sunday night, which was pretty amazing. He wanted to shop when the store was basically closed and he could just do his thing. David Johansen. The list goes on. That’s just how it was. People didn't have stylists, but they were portraying their personalities and how they felt through fashion as well as their music, so they knew better than anybody what they wanted to wear.

One of my personal favorite moments in the store was with Bruce Springsteen. I’m a big fan. He would come in quite regularly and one time he came in and as I said earlier, we did vintage clothing at that time as well. So I had found this perfect pink and black flannel shirt in the rags and it was in such poor condition that I couldn't even put it out. I dry cleaned it, and had somebody take the pockets off, and the patches off. It was crazy. And he came in and he just said, “Ray, you gotta sell me that shirt.” I said “No, it's a mess.” He said, “Please sell me that shirt.” And I said, “All right, you know what? Just take it. Have it.” And that's the shirt he ended up wearing on the cover of The River album. He sent me this huge blow up of him, “Dear Ray, thanks for the shirt, Bruce.”

Amazing. I'm sure there's a long list, but are there a few items over the years that have graced the racks at Trash and Vaudeville that come to mind when you think of stories like that?

DG— Marky wore the silver jacket.

MR— The silver leather jacket, like a motorcycle jacket. So beautiful. I wore that everywhere. Everybody would ask me, “Oh, where did you get that?” and I’d say Trash and Vaudeville.

RG— There are certain things, like our black jeans for example.

MR— I mean, my whole band wore them.

RG— And that was the first thing that we actually ever manufactured for the store because there was such a demand for it. People would come in and say, “Do you have any black jeans?” So I found a couple guys who had a little factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn underneath the bridge; it was South 5th Street or something like that and they started making me black jeans. That was the first thing that presented us as manufacturers.

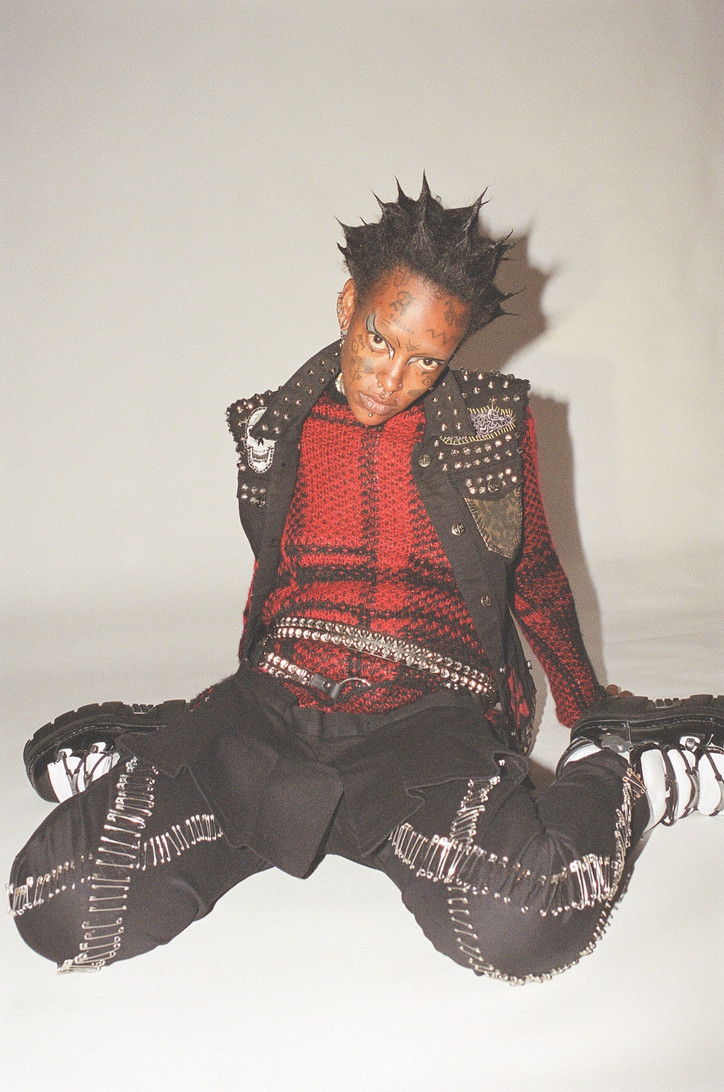

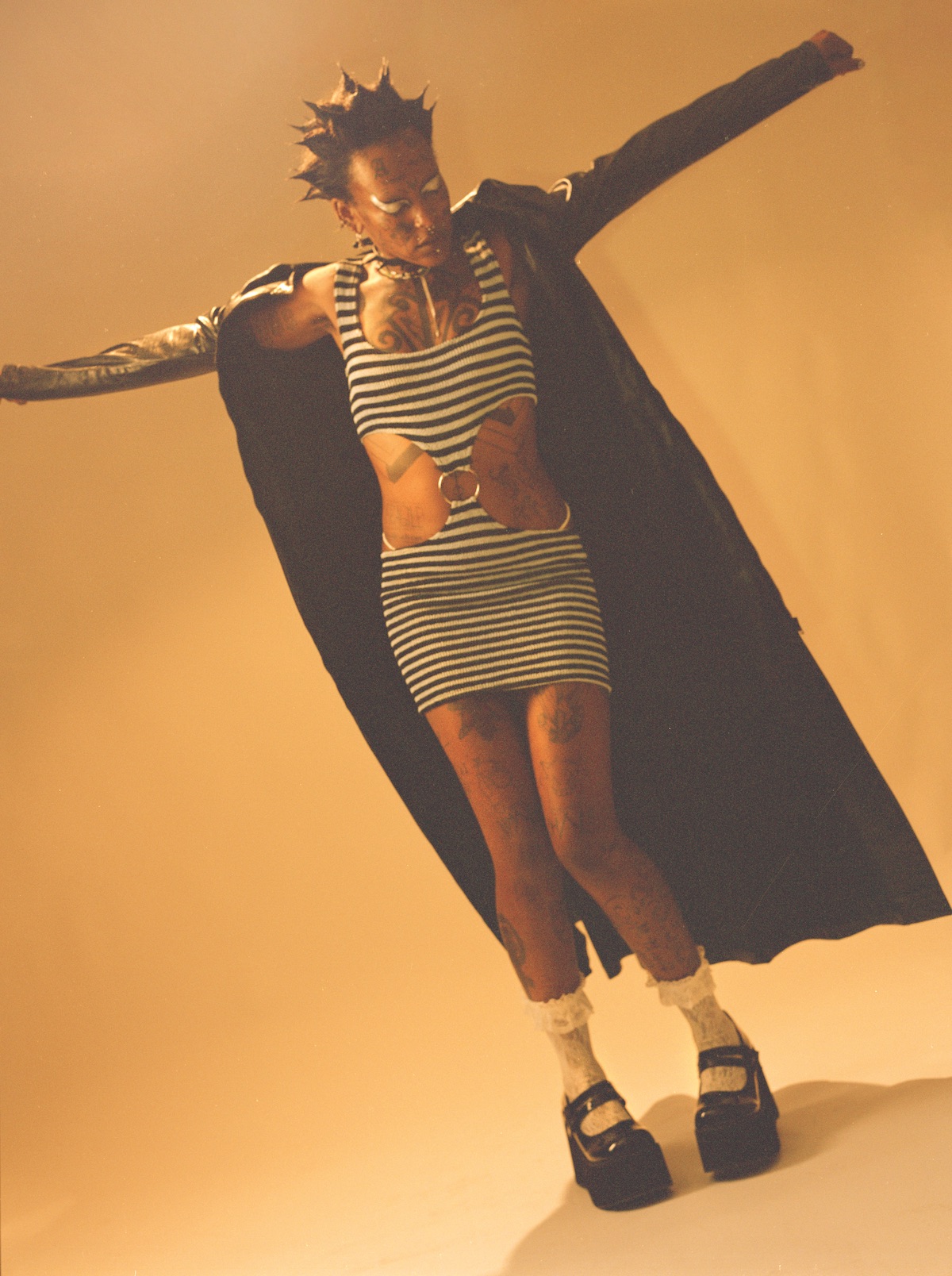

TINK wears FULL LOOK by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE

It’s a nice segue, because I did want to ask about Tripp, when it was founded and when you decided that you wanted to be making more stuff yourselves. Daang, was there an objective to Tripp at the beginning or was it more of a creative experiment?

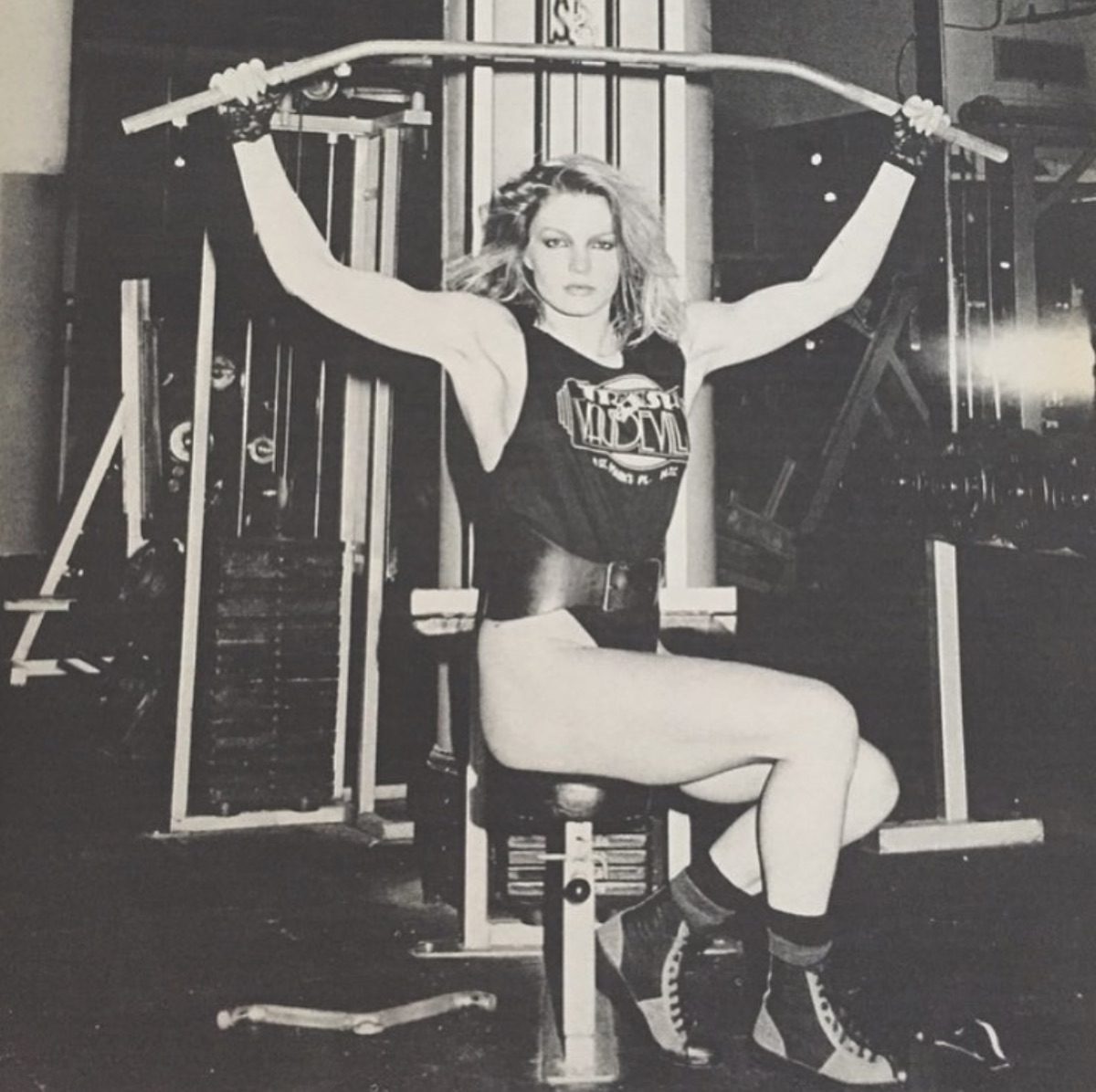

DG— When I moved to New York, I already always made clothes for myself. I’ve been sewing since I was eight. Ray liked the stuff I made and one day was like, “Why don’t you make a collection for the store?” and that’s how we started it. We would go to lower Broadway to buy fabric, sometimes go to Jersey to get things printed and then we found a factory, made 36 pieces and put it in the store.

RG— The impetus to do it was that we realized there was stuff that we wanted that we just weren't able to find, so we figured, let's make it so that somebody would come in and get inspired, or on the other hand, someone would come in and inspire us and we’d think, “Oh that’s really cool, we should have that in the store.” Eventually one thing led to another to where that grew into a really important part of the business and then we started getting approached by stores in other cities that wanted to stock Tripp.

DG— We got a cover at Detail magazine. Annie Flanders [the editor at the time] put it on Boy George, the buckle skirt with a leopard print or something like that and then we went to the release party and Suchi [Asano] — at that time she was Iggy’s wife — was wearing a Tripp snake skirt and we became very good friends too. At that time a lot of girls were wearing Tripp and now it’s a lot of guys, like now we do 50% menswear. The thing about Tripp is that it doesn’t wear you, you wear the clothes. It’s about the artist. I think that all of the Tripp and Trash customers are artists themselves. They’re creative and they appreciate the work that goes into every piece. It makes them feel like themselves and the adjustable details allow them to express themselves.

RG— Our approach has always been: “This is what we have, you put it together the way you see it.” 99% of the time their visions look amazing.

REEF wears FULL LOOK by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE

So, in a landscape that is trend-based, what helps the staying power of a shop like this or of a band like the Ramones?

DG— Well, we wouldn't be here without our kids. We have two kids, our son Lucas and our daughter, Cassie.

RG— Cassie really keeps us current in the modern world, whether it's with the ecom business, and also all the photos, all our social media, even style input. As we're getting older and everything, you know, we really need her in there. She's been working with me since she was six years old.

DG— Our kids grew up at trade shows, traveling with us for business, and they’ve always had a lot of inspiration and a lot of influence in our lives.

RG— And our son Lucas, he has a band, Lion Babe. He was a music industry major at Northeastern, but he spent summers working in the store when he was going to school. He has been very influential on the store.

And when it comes to the Ramones, the music speaks for itself. I mean, it doesn't matter where you come from. I don't even think you have to understand English to understand it and get into the energy of it. And it’s fun, it makes you want to jump up and move.

ELLIOTT, 24

Marky, in your experience, is that something you like to do? Are you altering your own clothes? Taking something off the rack and making it your own?

MR— Well what it is, I just wear clothes until I wear them out. [laughs]

I guess that’s altering the clothes, but sort of in slow motion.

MR— Well yeah that’s what I’m waiting for, is for them to wear out. Holes in my jeans, you know, just something that magnifies my personality. You know, you play live, you exert yourself and you do it every day. And the next thing you know, you get a nice pair of jeans, your jacket’s worn out, you can move. But Tripp’s everywhere. I travel all over the world and I see it and it’s amazing.

DG— And we are just beginning. I think just like with Marky's music, young people now are still discovering it. It’ll never die. It’s about that age, that same age — makes your heart beat when you hear it the first time. And now it’s even better, it’s not just the East Village, or New York, it’s everywhere. Like our clothes now have crossed over to rappers. Just the other day Lil Uzi was wearing it on the Tonight Show or something with the whole band.

RG— Daang has done custom stuff too, like for Rihanna. She did all the jumpsuits for Migos when they went on tour with Drake a couple of years ago. She did all of that and it’s so great. Everyone interprets it the way they want to wear it.

DG— So we stay at 1-2-3-4, stay the same. We keep the beat.

RG— Right, we’re not gonna wake up one day and say, “We're only making three piece suits.” What we make is going to be within our world, and in our world, we’ll experiment. It doesn’t always work so we try something else. We just keep moving and try to keep it going.

DG— I think living in New York City, a lot of people listen to people too much, care too much. You should do what you're happy with and be a good person and make stuff that you want to wear. You don't have to get approval from anybody.

RG— You have to be willing to put the work in. One slip, it's not the end of the world. You know, you just go back and rework it and do it again.

MR— I have a theory when I play the drums. I don’t usually make mistakes, but if I make a mistake, I'll try to do that same thing twice as if the first one I did wasn't a mistake.

DG— One slip is good, because you learn from it. You just stay at it.

TINK wears FULL LOOKS by TRIPP NYC courtesy of TRASH & VAUDEVILLE