Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

During the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale, London-based gallery Unit London presented In Praise of Black Errantry. The show comprises 19 modern and contemporary Afro-diasporic artists, including the likes of post-modern pioneers and New York City natives Jean-Michel Basquiat and Romare Bearden, alongside post-post-modern artists such as Rachel Jones, Hilda Kortei, and Jonathan Lyndon Chase. Based on French philosopher and writer Eduard Glissant's definition of errantry, "a mode of freedom and resistance, evoking a spiritual or purposeful wandering beyond national borders," the show celebrates the boundless Black imagination in contemporary art.

In Praise of Black Errantry will be displayed from 17 April–29 June 2024.

Curated by art historian Indie A. Choudhury, the exhibition offers an expansive interpretation of errantry: "Errantry opens up alternative ways of thinking and perceiving, affording creative disorder and the reordering of narratives, histories, and temporalities. All roots (routes) lead to the imaginary." Errantry, as shown by the artists in the exhibition, is the unbridled ability to dream and create without the constraints of nationhood, predefined borders, or colonial inheritance.

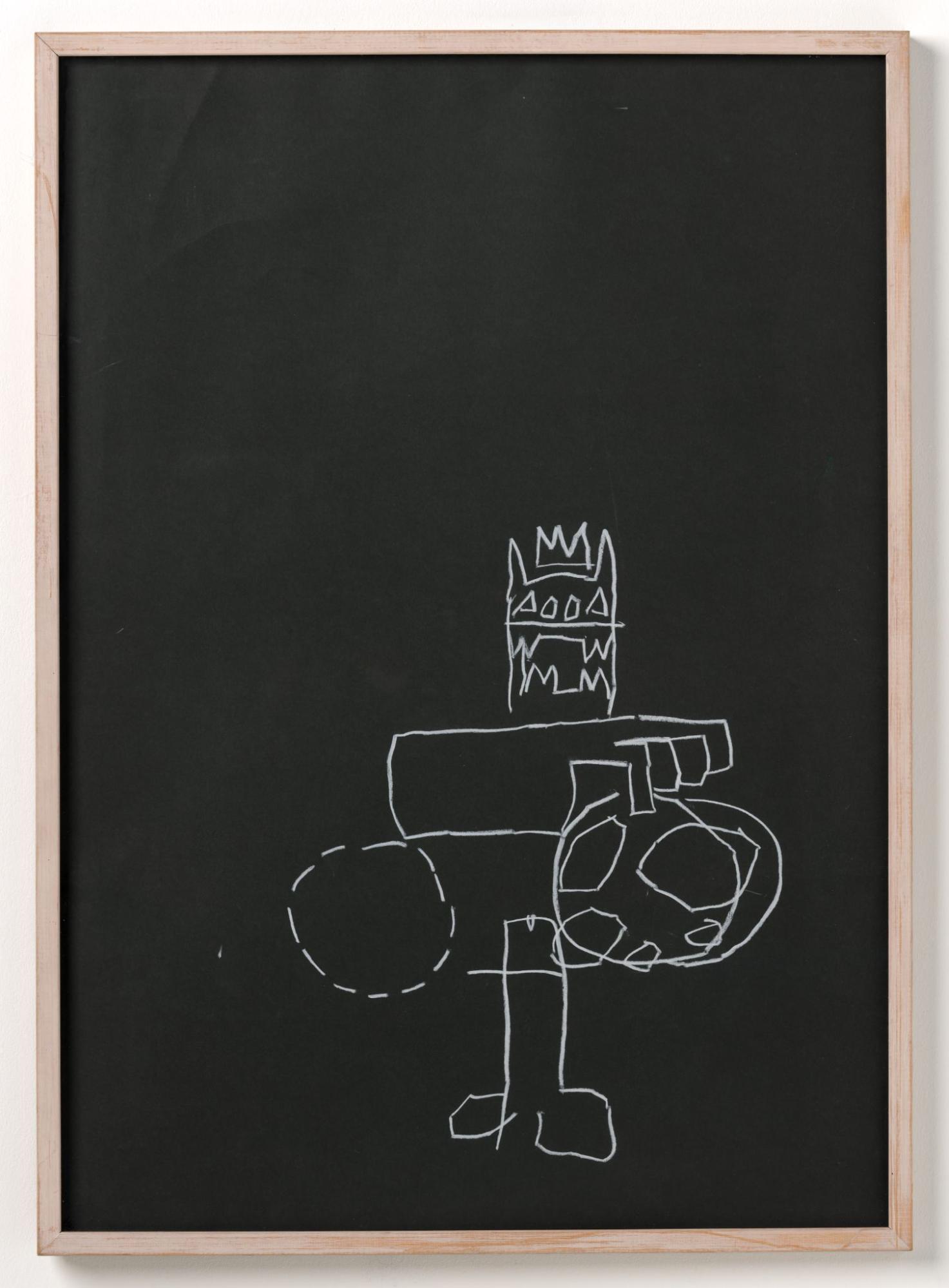

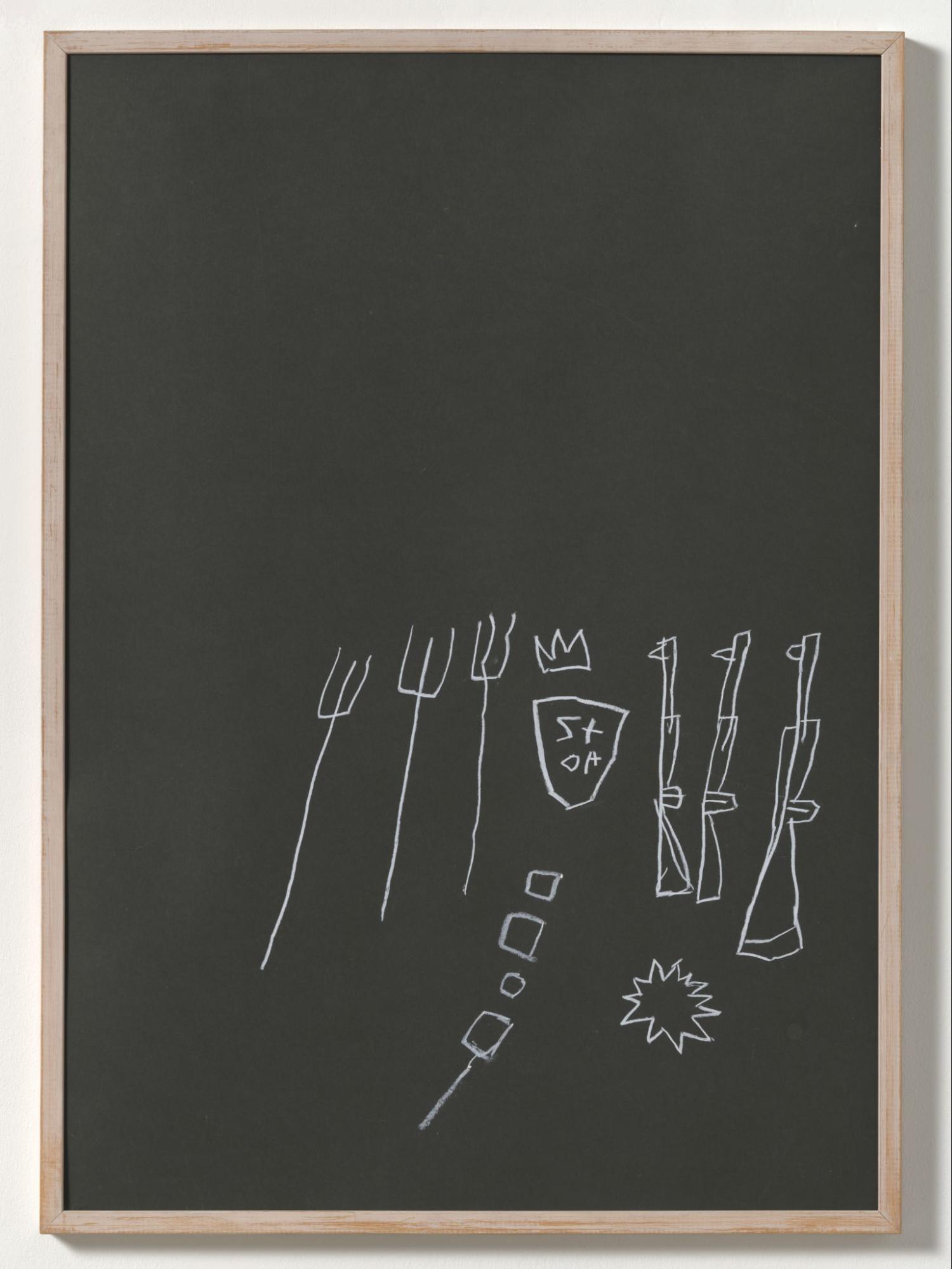

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Samo I and Samo II (1981)

Never is errantry more apparent than through the works of Basquiat and Romare Bearden, two New York artists at the center of In Praise of Black Errantry. Basquiat's work uses movement and broken imagery to create his errantry, rejecting the typical Western perception of what constitutes 'good art' and making his distinct visual language. His two works on display, Samo I and Samo II (1981), show fragmented images, a monstrous figure, and an explosion on a flat, dark background.

Romare Bearden, Seance (1984-86)

Bearden mirrors Basquiat in his use of fragmentation, using collages and bold colors to portray movement, music, and displacement themes. In Seance (1984-86), Bearden employs a blend of watercolor and gouache, resulting in rapid drying that gives rise to several figures distorted into monstrosity by their fluid interaction with colors; though not fully formed, their presence remains distinctly palpable. Bearden creates no divide between the figure and movement, blurring the lines between classical figuration and abstraction.

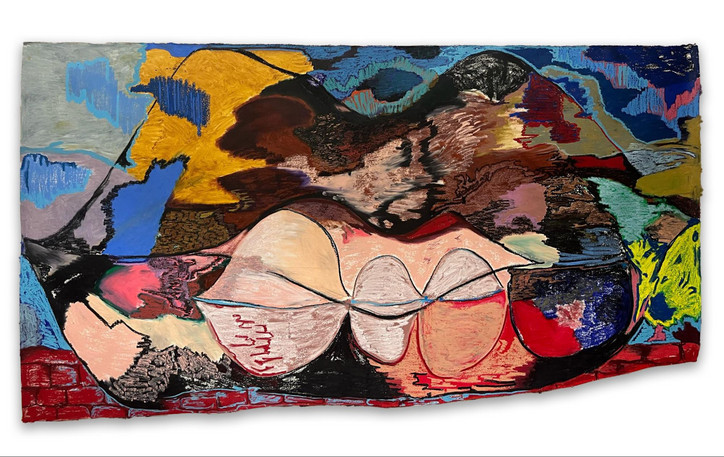

Rachel Jones, !!!!! (2024)

The influence of Basquiat and Beadern can be seen throughout the exhibit, as fragmentation, movement, and color are employed to explore post-postmodern errantry. In Rachel Jones's painting !!!!! (2024), bright, rich, abstract color islands float across the canvas, reminiscent of the ever-moving watercolor of Bearden. The artwork is unstretched, and the bottom is uneven, emphasizing its imperfection and materiality. As the title suggests, the painting is pure, intense emotion conveyed by the unbridled joy of her color and movement.

Hilda Kortei, Demur (2023)

Similarly, the painting Demur (2023) by Hilda Kortei uses a mixture of mediums, oil, acrylic, and charcoal, on fragmented collaged canvas to create a sculptural and layered painting. It defies the traditional conception of how a painting should be constructed and instead utilizes its flaws to create a multilayered cacophony of movement. While the hesitant title Demur is at odds with the excitement of Jones's !!!!!, both works employ similar techniques to build errantry. Neither work is static; each feels like it is ever evolving, a sentiment shared by all works in the exhibition.

In Praise of Black Errantry is a striking and unique exhibit. Within the larger context of the Biennale, whose theme this year was "Foreigners Are Everywhere," Unit London takes the opportunity to celebrate the non-conformity and limitless creativity of Afro-diasporic artists. By foregrounding the voices of marginalized communities and embracing the ethos of errantry, the exhibition transcends the limitations of cultural persistence and political containment. As curator Choudhury describes, the artists in the exhibition "take up errantry as a radical strategy that defies boundaries and advocates for spontaneity and experimentation beyond cultural fixity or political containment."

Over the past year, she has been extremely busy working on a variety of different projects across the world. She designed three collections, with LQQK Studio, Big Love Records and Perks and Mini. She released a zine with Commune Press with fellow tattoo artists Keegan Dakkar and Jackson Epstein from New York as a prequel to the group show ‘Songwheel’ they did together in January at Commune’s Gallery in Tokyo. This year is planned to be just as full on for her. As a fan of Coco and her work, I wanted to sit down with her and talk about her work and her projects before she moves to Tokyo next month.

I wanted to start by asking about tattooing which seems to be your main practice as of late. How did you get into tattooing and was it a natural transition going from drawing?

Drawing has always been my happy place and I think tattoos are just an extension of that. I got my first tattoo when I was fifteen. I wore an outfit that I thought looked really grown up and hoped they wouldn’t ask any questions, thankfully they didn’t. I really enjoyed the experience of getting a tattoo. I started doing terrible stick and pokes with my friends when I was in high school, we would get sewing needles and tape them to pencils and use pen ink. Then it grew and at parties’ people would ask me to do it. It got to the point when friends and friends of friends started asking if they could come over for me to give them a tattoo after school. When I was at art school people started asking me to do drawings for them to get tattooed. I was spending a lot of my time doing stick and pokes and doing drawings for others. I wasn’t thinking of it as a career, I just enjoyed doing it. People offered to pay but I thought that was ridiculous and refused for a long time. Then there was this one time when my friend who was visiting asked if I could give him and his friends these matching tattoos to commemorate their friendship, they’d buy me a six-pack of ciders and we'd light off fireworks [laughs]. That night I realised just how much I enjoyed tattooing. After that, that’s when I decided to commit to it. I bought a machine, made Flash, got a mentor, started practising on lemons and my friends, quit my job and that was it.

When did you quit your job and start tattooing full-time?

I think I was 20 or 21, so it’s been sixish years now. In 2020 and 2021 Melbourne was in lockdown for basically the whole time so I couldn’t really tattoo for most of those two years. Then I’ve also done some travelling before and after, so I haven’t been consistently tattooing the whole time. In the scheme of things, it hasn’t been very long.

Wow, I didn’t realise it’s been so long. When did you develop the style of tattoos that you are doing now?

I have always just made tattoos in the style that I would want to get myself and things from my other drawings that people asked for. When I started, they were more scribbly and doodly because I wanted ones like that and also because I wasn’t very good [laughs]. I would say during lockdown when I had a lot of time to sit, and draw my style shifted more to what it is now.

Your style is so unique. Where did the influence for it come from?

I have always been really interested in creatures, world-building and storytelling. I read a lot of sci-fi, I watch a lot of movies with special effects, I love trail running and get a lot of inspiration from nature especially Australian flora and fauna, space, my friends, and I really love puppets and animatronics. Those are all such big influences on my work.

Can we talk about your love of puppets?

Yeah, I used to spend a lot of time at this puppet shop/theatre called Hocus Pocus when I was a kid. I would have every birthday there. It got to the point where the owners would put out birthday signs on the month of my birthday because I spent so much time and all of my pocket money there [laughs]. It felt so big at the time, like I was stepping into another world. I have gone to visit where the shop once was since, in reality it’s just a small place, the store has changed into many other things over the years, but it still feels nice to go in.

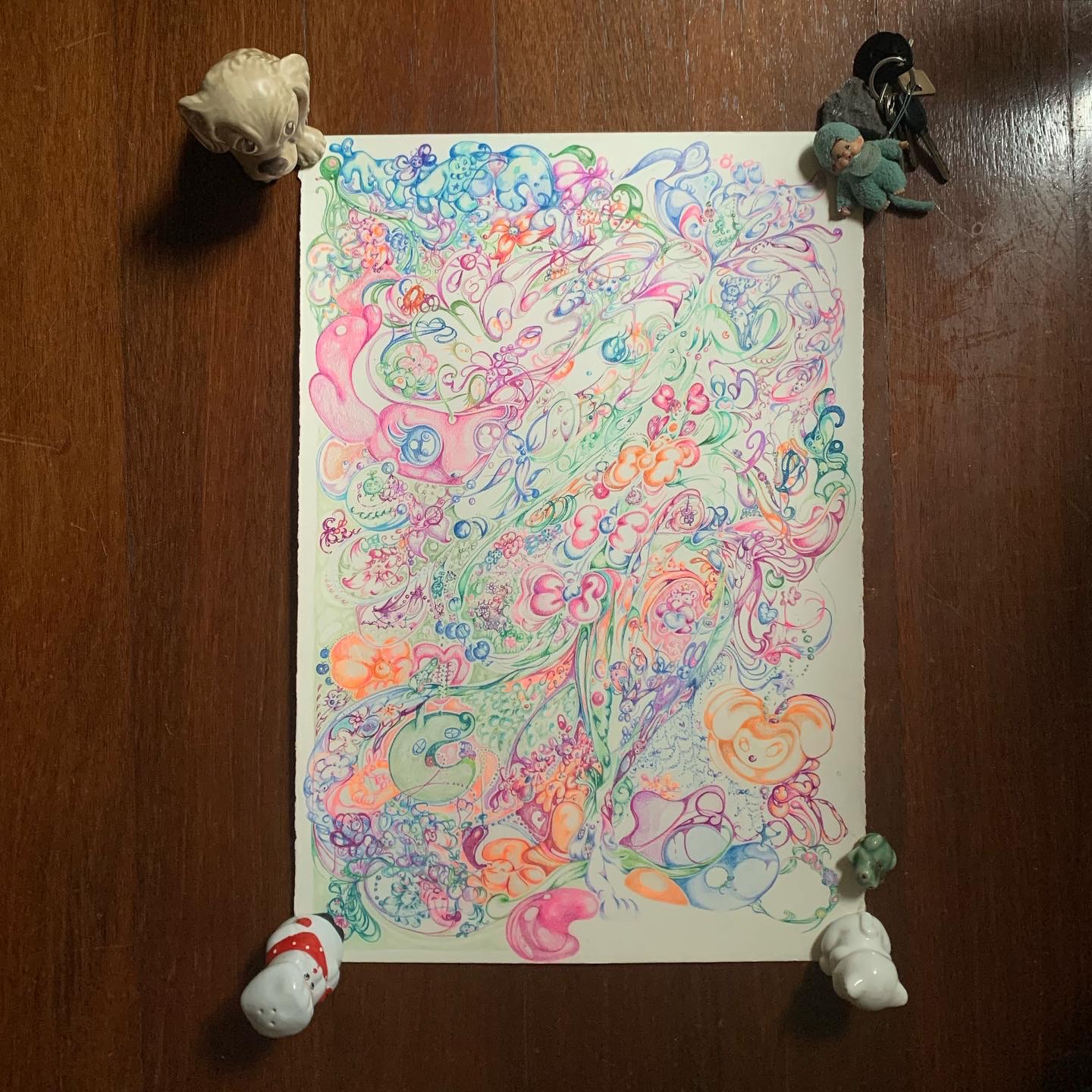

A lot of your recent drawings have been centred around the theme of perception and shrimp vision, where did the influence for that come from?

I love theories of perception. I really like looking at how other creatures see things and make sense of them compared to humans. My favourite creature is the mantis shrimp, the mantis shrimp has the best vision of any creature in the entire world. Humans view the world through three channels of light and the mantis shrimp views through twelve and they can see UV. They see a whole spectrum of colour and light that is so beyond what we can even imagine. A big focus in my work is imagining how the mantis shrimp would experience the world. That is what the big focus of my recent show with Commune Gallery was, trying to play with colour that created a spectrum in the way I imagine they are morphing colours in a way we can’t perceive.

Do you think that’s where your use of coloured pencil comes from?

Yeah, definitely.

While you are out in nature are you taking photos of things that you’d take influence from?

Yes, or I take them home [laughs]. A lot of feathers, rocks, lost buttons and things. As I’ve been moving I’ve been getting rid of a lot of it, but I bring a lot of things home. A lot of what’s in my drawings is from something I’ve found or has some kind of story behind it.

Do you have an example of a bit of your work that has a story in it?

This little creature with robo-tentacles in this one part of this drawing. An old friend of mine is working on a project making birdhouses to help keep swift parrots safe from sugar gliders. I was thinking about how sugar gliders are so cute and it’s funny to think they are the villains in this situation. I saved some photos of sugar gliders when I was reading about the project. That same day I took a photo of a Spider-Man balloon to send to a friend of mine that loves Spider-Man. The two photos were next to each other in my camera roll. So, I drew a sugar glider with these big Dr Octagon arms to represent their villain-hood in this story.

That is so cool, it’s something that the viewer would never understand, but it means something to you. Is it something you think about when you’re drawing and putting in these little personal easter eggs?

I’m not trying to make it something people won’t understand on purpose. People can take what they want from it. I want looking at my drawings to be like cloud watching, where the viewer can get lost in it and constantly find new elements or make sense of different parts in different ways.

Where do your characters come from?

All of the things that I have been talking about. I also get a lot of inspiration from seeing images in things like droplets of water or in the pattern on a machine. I see a lot of things in droplets of water when I’m in the shower.

Your latest zine, ‘Sixteen Rollercoasters’ that you made with Stacks Bookstore in Tokyo focuses on some of those characters. Can we talk about the zine?

The infinity symbol looks like an eight, two eighths make sixteen, which in my mind is double infinity. As infinity is infinite, in theory it can’t be multiplied so I like the idea of multiplying the un-multipliable [laughs]. It is also a reference to a song by Rammellzee called ‘Seventeen Roller Coasters’. I like the idea that by “doubling infinity” it is still one behind Rammellzee. I made this zine to zoom in on specific characters within my larger drawings that are particularly special to me. It’s printed on this pearlescent paper that sparkles in the light.

You are doing so much at the moment and it goes across a wide variety of mediums, whether that be clothing, drawing, tattooing, food and design. How does it feel having that much creative freedom to be able to not be limited by the medium?

I have never actually thought of it like that. I like trying new things and making things with my friends and have always been excited by collaborating with others to make something neither of us could do alone. That is one of the big things with tattooing for me too. I see the characters as little friends of mine and when I tattoo them on someone, they become that person's own little friend.

Working with different mediums you can stretch your ideas so much further. Do you ever feel limited by drawing and tattooing?

I haven’t ever felt particularly limited by these things. I see drawing and tattooing as just part of what I do in the bigger scheme of things.

Are there any other mediums you could see yourself working in?

I would love to make more sculptural pieces and furniture at some point.

You’re also designing a donut, right?

Yeah, I’m designing a donut for Juanita Peaches which is a café owned by my friends. They are doing a series of different donuts throughout the year, and they reached out to me to design a donut.

How does designing the donut work?

So, I come to them with my flavour ideas and what I want to do with the design. Then I work with the pastry chef, and she takes the ideas I have and works out what is realistic and what can work.

What drives you to create?

I’m not sure, really. I think storytelling and connecting. It’s important to me to work with friends and people whose values align with mine. All the projects I’m working on at the moment are with people I feel very lucky to have in my life. That definitely helps drive me.

What’s next for you from here?

I am moving to Tokyo next month, so I am currently packing up my apartment. I am working on a new collection with Perks and Mini that will come out at the start of next year. I worked with them on designing some pieces and I have really enjoyed the process. I am also working on a three-way collaboration with Geek Out Store and Commune Gallery. I have some other projects that I am working on now that I am really excited about.

The Jamaican-born, New-York based artist has long been fascinated by objects. His best-known work, Amazing Grace (1993), featured over three-hundred baby strollers that the artist scavenged from the streets of Manhattan and then installed in the walkway of an abandoned Harlem fire-station. A statement on the AIDS crisis and drug epidemic ongoing in New York at the time (the strollers were often used by the city’s homeless population), the piece foregrounded Ward’s focus on utilizing found materials to tell stories that their human counterparts could not. Over the next three decades, the artist continued to work with such materials — shopping carts, bottles, doors, television sets, cash registers, and shoelaces included — and translate their silent language into a more readily accessible dialogue. The resulting practice is one filled with intimate links to the world around it: it sings of previously undiscovered connections, alerting us to the unspoken ties between us and our possessions.

Nari Ward: Ground Break (28 March- 28 July 2024), a retrospective at the Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, offers an up-close look at this practice through a number of Ward’s sculptural installations and video works. Curated by Roberta Tenconi with Lucia Aspesi, the show begins with Hunger Cradle (1996-2024), one of the first large scale installations that the artist created in the 90's as part of the “3 Legged Race” exhibition in New York. A complex network of interlaced threads, Hunger Cradle unveils found objects — car parts, fire horses, a piano — that Ward collected from around the original show’s building and then embedded in the piece’s structure. Here, the work has been further enriched by new materials sourced from around the Pirelli HangarBicocca, including bricks used in the exhibition’s titular piece, Ground Break (2024), a sprawling floor installation made of over 4,000 concrete bricks and topped with decorative spiral motifs that resemble celestial bodies.

Although not the exhibition’s center piece, it is Hunger Cradle (1996) and its implied sense of support that best serve as a metaphor for what Ward, or so the viewer might be led to believe, is trying to express. From the dead fish whose carefully skinned flesh line the floor of Super Stud (1994/2024), a small house propped up on metal studs in the exhibition’s main room, to the tangle of stray shoelaces that make up Tumblehood (2015), a spherical sculpture that mimics a tumbleweed, what emerges above all is the artist’s desire for preservation amidst the never-ending flux of life. There is a dash of the mad collector here, or perhaps something of the old Proustian goal: to regain what is lost. Still, Ward goes beyond merely accruing disparate materials or using objects to recount past experience; instead, he takes things in, provides shelter, then suffuses them with his particular magic, which is also his art.

The show, on view at the Pirelli HangarBicocca’s cavernous space north of Milan’s city center until the end of July, affords us a previously undisclosed peek into the minds of one of America’s most compelling contemporary artists. It —and its many oddities and beauties— is not to be missed.