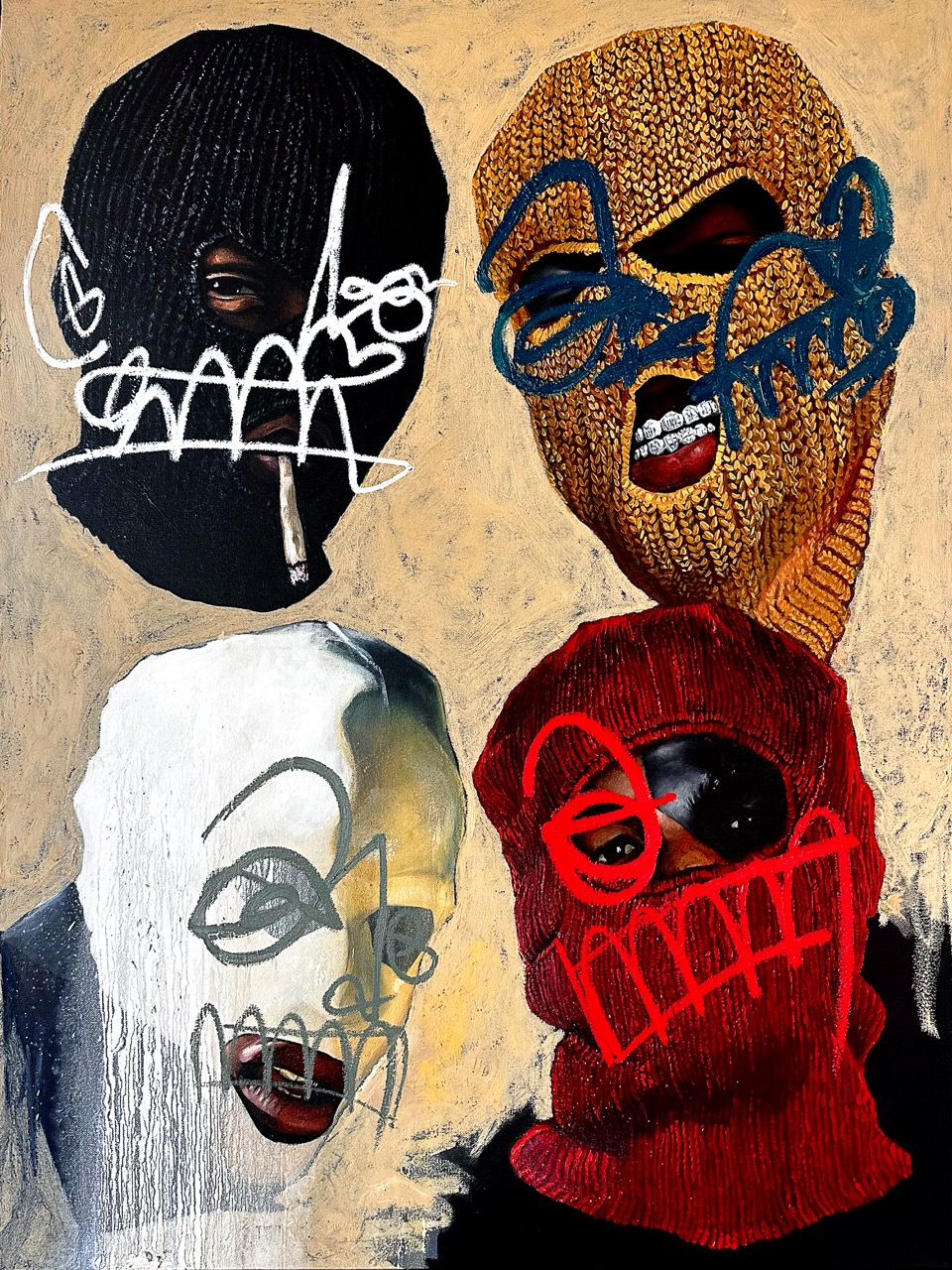

Eat My Face

That faces are products to be consumed is no great mystery—but here there is a double subversion, a concealment that heightens revelation, a revelation that heightens concealment. Identity becomes a tie-dye version of itself, questions of ‘who’ and ‘why’ melting into each other like trickling rainbow hues in a groovy optical imbroglio.

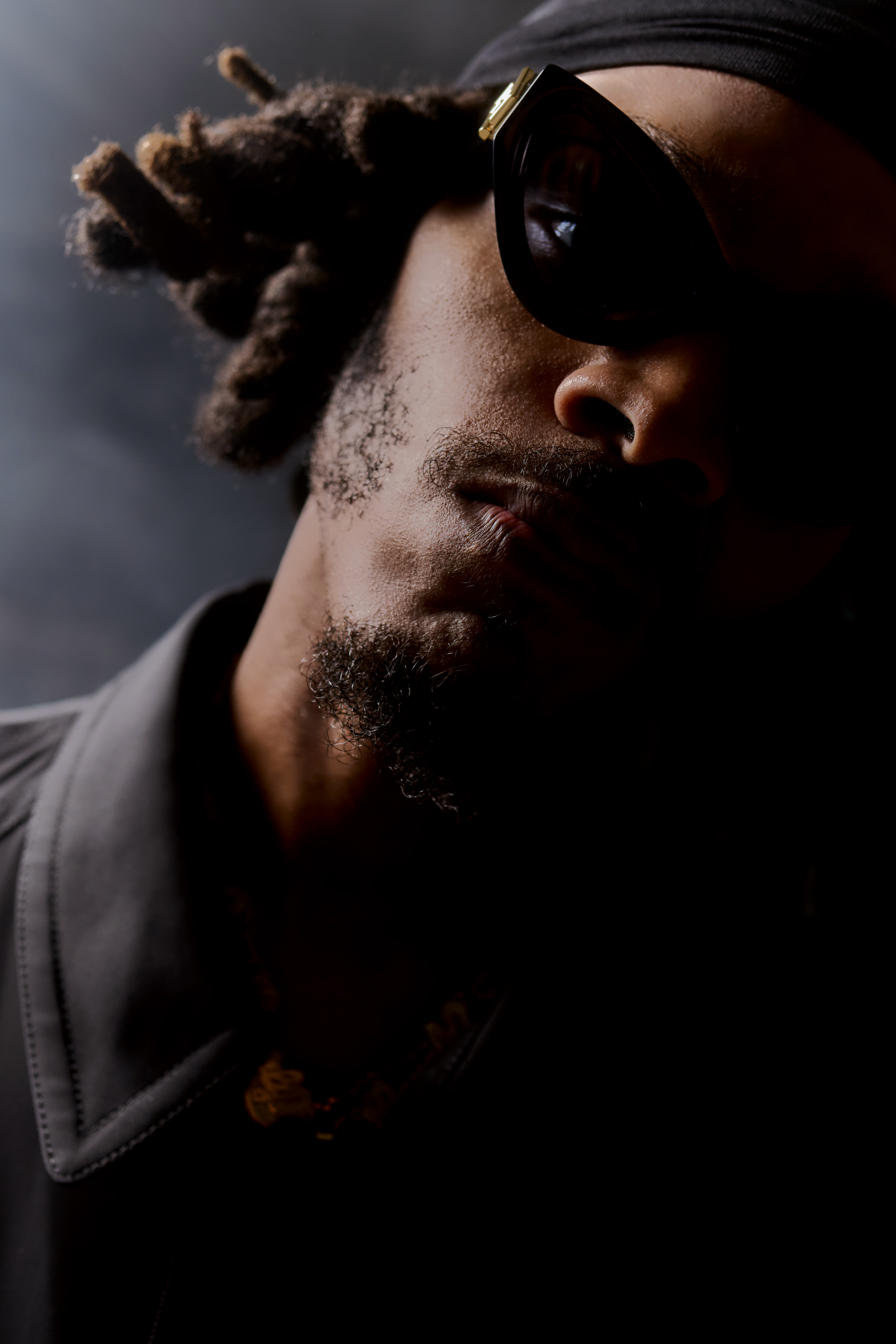

This could be due to the fact Nobody Jr. has turned social media itself into his latest artistic medium. Known for delightfully outrageous performance pieces that take place over long spans of time that are both playful and heady (in the interview below, the artist describes his fake 2000 campaign to elect Donald Trump president—a bizarre, legendary Cassandra moment if ever there was one), it is little wonder that he has made the point of his presence on Instagram to subvert and investigate the platform itself. His use of costume, makeup, and surrealism form a poignant critique of how we shape our lives around social media, often using it as a way to create our own sparkly, surreal masks for the world to admire. I know I do.

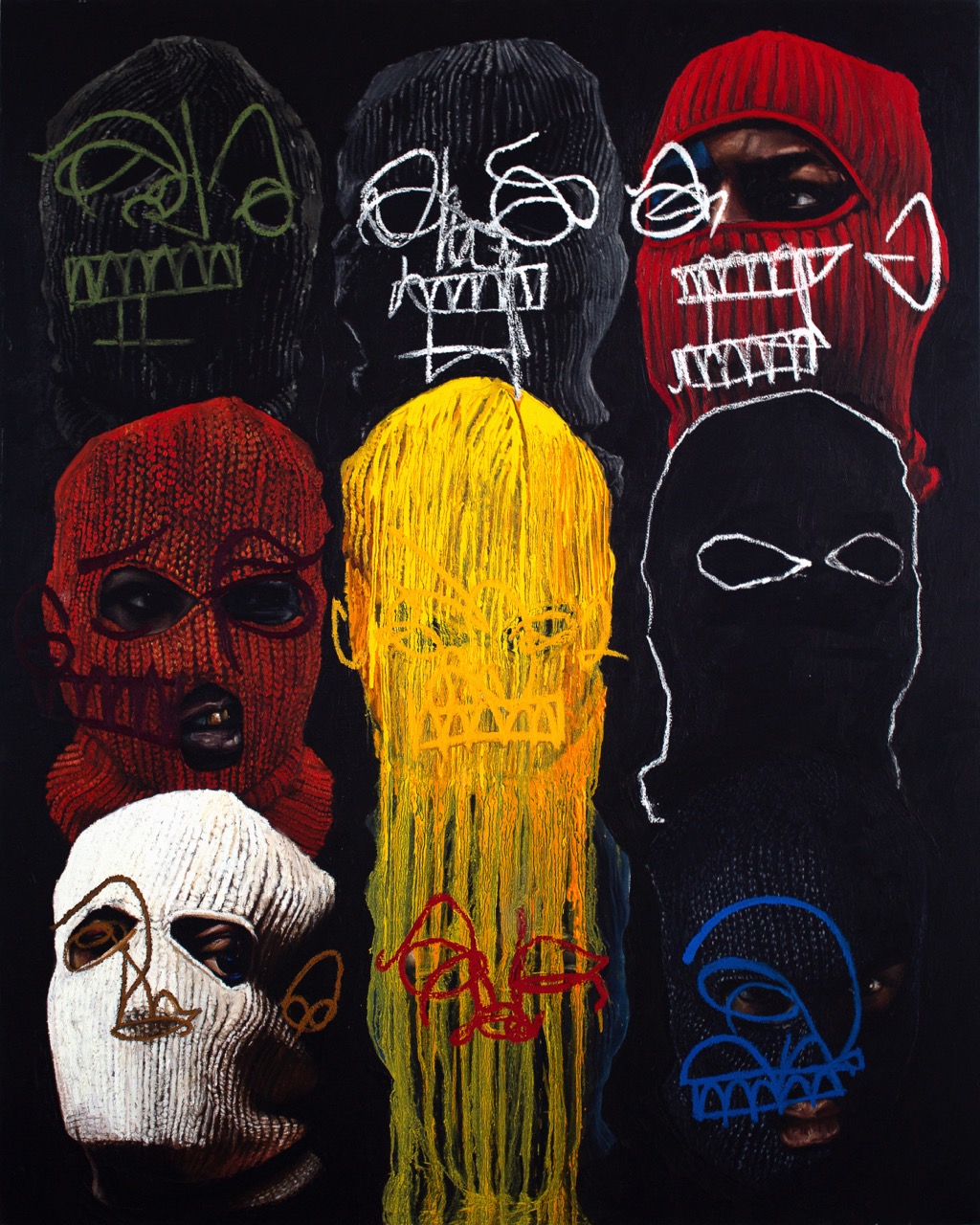

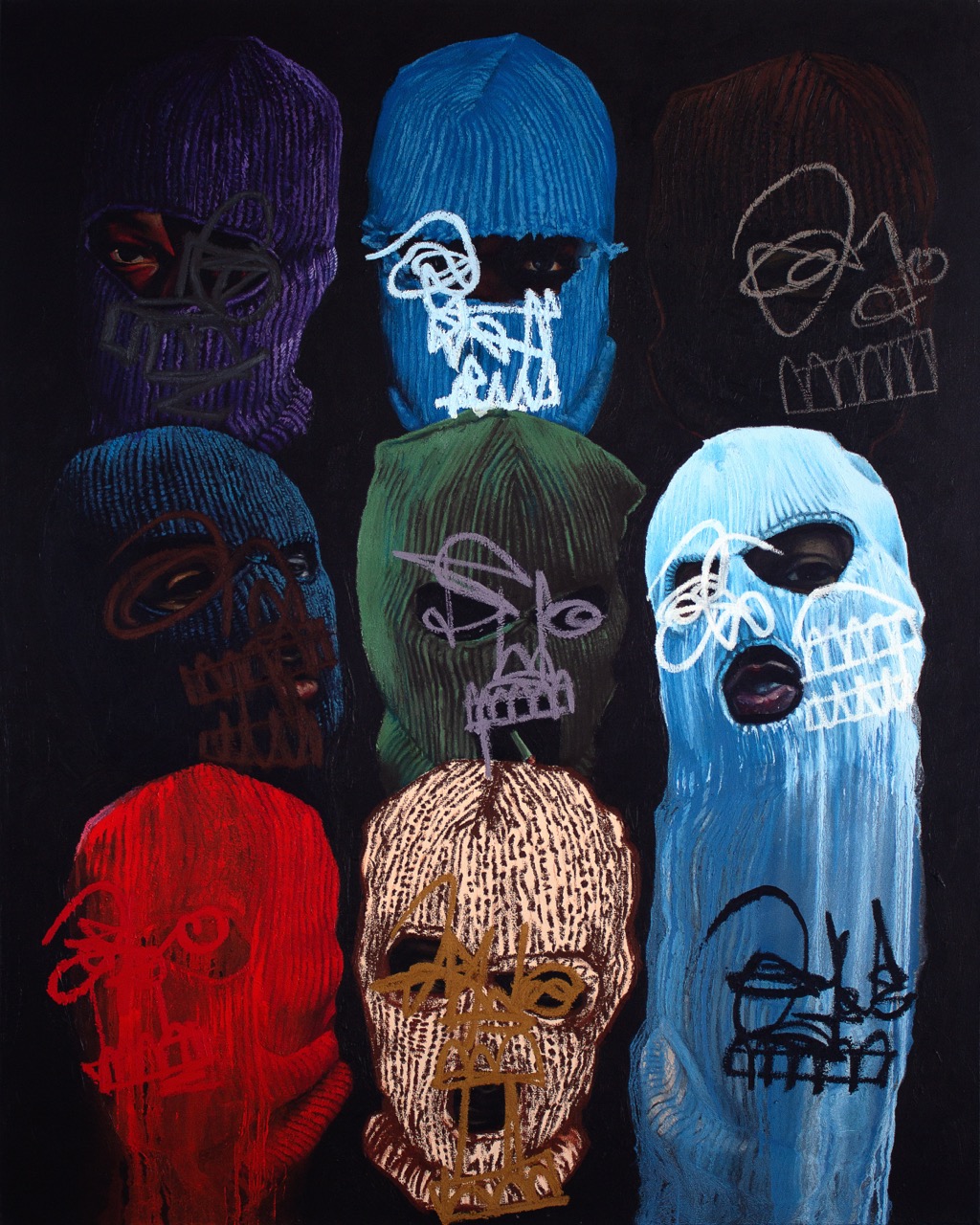

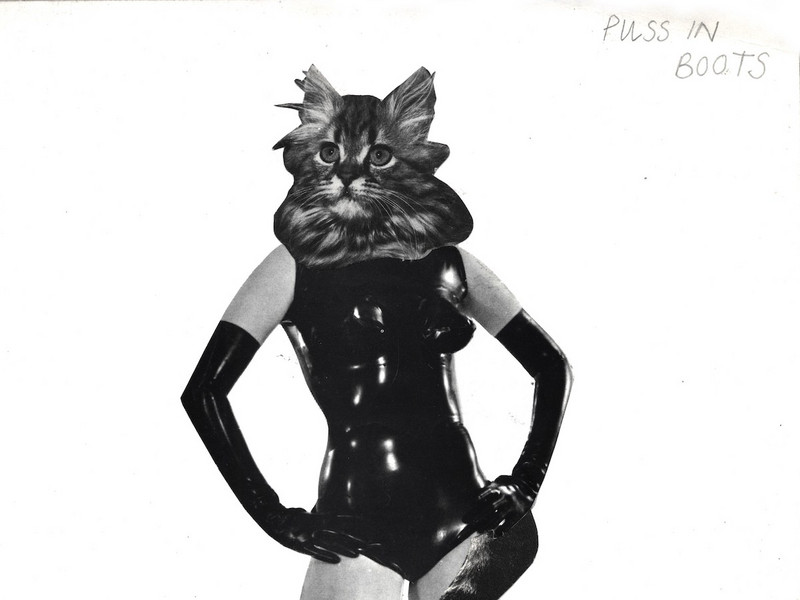

'Alfred E. Liberty' and 'Cavity Creep.'

I met David initially at a coffee shop in Brooklyn, and I’ll be perfectly frank: I was surprised he wasn’t twenty-something, which is perhaps testament to his ability to create masks. In person, he’s a bit like Tony Hawk—forever young, cool, and svelte, but nonetheless not without the signs of living hard and fast in the '90s. He reminisced about how drivers used to carry baseball bats as he walked me to his studio around the corner.

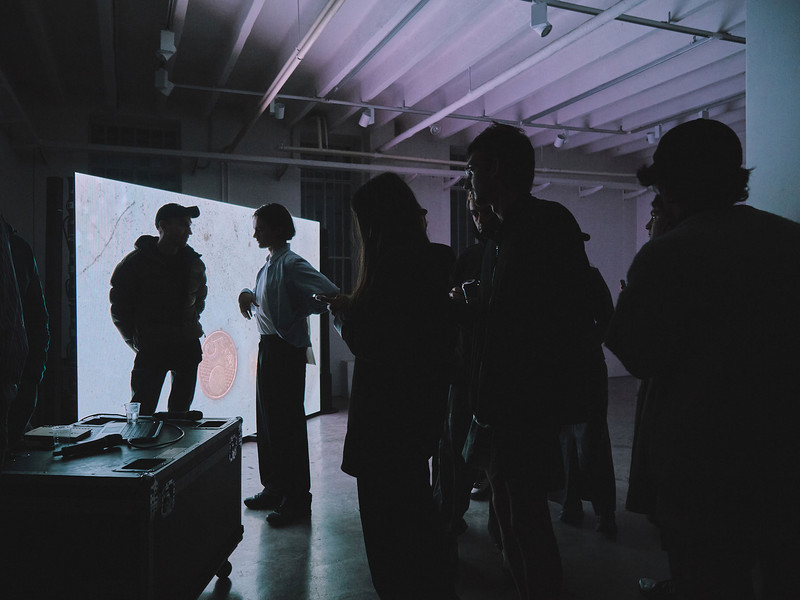

Upon entering, I was immediately delighted by his two cats, who took a shine to me and I to them. While tea brewed on the stove, the artist walked me around the tidy living space and showed me the controlled chaos of his studio—a wall of wigs, an immobile mannequin, shelves full of dolls, the splendid clutter of a hyper creative mind filled me with a familiar joy. Once the tea was poured, we began to talk about his performance the night before at Contra Gallery, his punk rock influences and the importance of garbage, among other things.

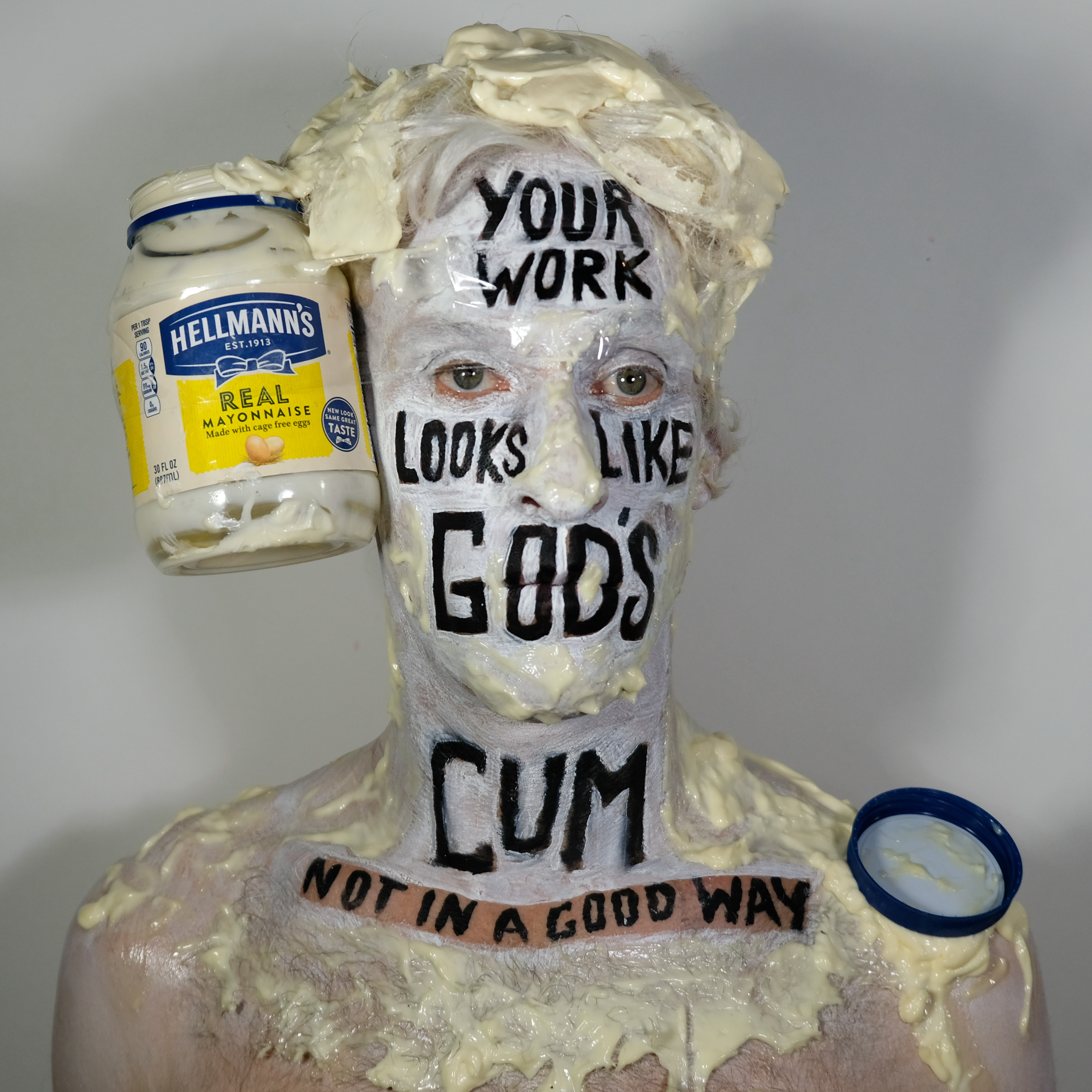

'Cheetos Trump' and 'God's Cum.'

Tell me about the current body of work.

I call the current body of work ‘resemblage.' It’s a word I made up—a combination of the word ‘resemble’ and ‘collage’ and they’re kind of meant to look like CGI or PhotoShop, but everything is done physically and is real. I use food and food scraps, waste, consumerist detritus like weird garbage I find, weird props I find in junk stores, whatever catches my eye. Some of them are highly pre-meditated, like, ‘Hey I want to make myself into the Hamburger Helper guy,’ for example, which I did—I covered myself in a pound of hamburger meat; and some of them are more stream-of-consciousness, kind of improvised. They take anywhere from two hours to a few days, and sometimes I’ll do multiple takes. If you look at my camera roll on my digital camera, you can see from start to finish—I’m just trying different things on my face, and making recordings. As I make them I kind of transform into something else—I almost brainwash myself into being something else. I’m trying to get my subconscious to come out, so I sort of trick it to come out. It’s smarter than my ego, my intellect, on a certain level, it’s my intuition.

It’s interesting that you’re using food to do that, because it’s so connected to the body.

Food usually moves through your body, but in this case you’re wearing it. When you wear stuff, I feel like you feel it in a different way. When you’re so used to eating food and digesting it, you don’t really think about what you’re doing because it’s so reptilian, it’s so primal. But when you wear food—I don’t know whatever it is, but you’re wearing it and taking photos of yourself and it reinforces to your mind that you’re becoming this food or whatever the objects are. I morph myself to it. I create a relationship with the face paint, the sculpture between the thing and myself. It becomes much more symbolic by wearing it.

I also become a scapegoat on the internet, which I want to be—for whatever it is. If it’s McDonald’s and I become McDonald’s, it becomes political. ‘Why are you wearing McDonald’s?’ ‘Why are you wasting food?’ Well, I’m wasting because the subject is waste. When I wear it, it charges it more, I’m owning it, I’m taking responsibility for it, and people project at me. That’s why my Instagram has gotten bigger, too—because it’s provocative. It’s not just putting something on a canvas. I’m parodying it. It’s probably a bit annoying after a while.

Specifically, your Instagram is a part of this as well?

The working method of turning yourself into a symbol or an illusion in real life is a long-term thing of mine in all my bodies of work. This character, David Nobody, exists on Instagram and in live performances. It’s a character that’s creative. It’s like how a writer would write from a character['s point of view].

I do a little drag, so it reminds me of drag—you become a persona.

I’m for sure influenced by drag, yeah—it’s liberating.

Do you know drag queens?

I did a solo performance at MOCA Tucson in September, it was a great gig. The curator, Ginger Porcella picked me, and for that I collaborated with seventeen local performers and a lot of them were drag queens. It’d been a minute since I’d worked with drag queens. I had two of them in a bed with 150 pounds of peanut butter in it, and they were nearly naked and smearing, sexually, peanut butter all over themselves, and the audience’s jaws dropped. The performers came out on a runway, it was kind of a fashion show. It was called ‘Edible Wardrobe Malfunction,’ so it was a fashion show that was designed to completely implode and go insane. So, I had them as part of the piece, but there were many things happening concurrently, that’s usually how I work. But they were in this bed together rubbing peanut butter all over each other very sexually—the curator told me to shock the audience, but I know I shocked the fucking shit out these people, man. It was so good.

And this was in Arizona?

Yeah, but Tucson is a very blue city in a red state. It has a strong arts community and there are a lot of drag queens.

There is something about performance that is different from something hanging on the wall, it’s not still, it’s real people, it’s flesh and blood, and then to take something like peanut butter—even to see a bed made out of peanut butter would be a little shocking, somehow.

You’re bringing it into reality. There are more moral and ethical conundrums to it. It might be an image that sticks with you stronger, there’s smell, there’s sound to it, there’s time—so many different things. Performance isn’t the only way I work—I also work in periods where the characters actually want to make paintings. So, it just depends.

You’re kind of a changeling—a shapeshifter.

Sure, like David Bowie. The artists that I look up to changed a lot, too. But there’s always a voice. People say, ‘Wait, do you know who you are?’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, I always know who I am. Always.’ I just like to fuck with my reality a lot.

'Behind the Body of Reality' and 'Cerebral Cauliflower.'

That’s a good way of putting it. I love this idea of waste.

Wearing the waste.

How did you come to that—'wearing the waste?'

Well, I’m very critical of the United States, and this culture that we live in, in a lot of ways. I’m very critical of consumerism. But it’s also like, I’m hypocritical, too, because whatever I criticize I’m part of. It’s immerstionist—you can criticize it, but you’re part of the problem. I guess wearing the waste is coming out of a statement about that. But there’s a history of movements in music and art that have dealt with it, specifically, I would say punk—especially in the 1970s, if you study it, which I did a lot, and listen to it. Like Johnny Rotten from the Sex Pistols—they were like, ‘Hey Johnny, why do you guys wear ripped up, dirty clothes with safety pins and stuff like that?’ and he talked about how there were huge garbage strikes in the working class neighborhoods in London in 1977 and 1978, and the garbage people stopped picking up the trash. So, there were football field-sized mountains of trash. There was trash all over the place. This theme carried over—he said, ‘The only way to deal with the garbage was to wear it.’

It’s my own intuition to look to alternative culture, punk rock, drag queens—all this stuff. But it’s very important too that this work is influenced by the medium of the internet, and there’s a definite psychology to how I do it. I like to say that I realize more and more that the internet is a fascinating medium. It’s the first medium that looks more into you than you look into it—every time you look at it, it looks at you a thousand times. It’s a machine, it records everything you’re doing. It’s weird, and let’s not pretend that it’s not. So, the David Nobody characters are expressions of turning yourself inside out, in a way, because there’s a sort of clash between the world of appearances and the exposed world of emotions in this computerized reality. It’s bizarre. So, I’m trying to explore this [idea]. I definitely joined Instagram to deconstruct it, through this performance. That’s why there was this big press hook in the beginning—I was on BBC, I was on Vice, because they realized I was talking about social media in an exaggerated manner.

It’s hard to say, how art looks now and how art will look twenty years from now—maybe what I do now will look super fucking telling in the future more so than now. Or maybe not. I actually predicted the Trump presidency in 1999 in another body of work—this was before the Internet work, but I stalked Donald Trump for a year as a performance. I tried to meet him as many times as possible as a piece. He and the turd, Roger Stone—thank God he got indicted because he’s such a fucking dirt bag. I posed as a conservative Trump operative and tried to infiltrate the organization as a piece, basically. At the time, Trump was flirting with the media, saying that he might run for president. So, I was doing this piece and met him six times in one year. I have five 8x10s autographed in gold that are in a safe place—a friend of mine I told about them said, ‘Wow, you should hold onto those, that’s like having your picture taken with Hitler and having it autographed—those are going to be something some day.’ Anyway, he kept hinting that he was going to run for president, and there were no ‘Trump for president’ signs, and I worked with a graphic designer friend of mine and we made one. I went around in Manhattan, on Wall Street, a couple times with a videographer that I use, this guy Richard Sandler—he’s incredible—posing as a Trump operative. I took my ‘Trump for President 2000’ sign out and asked the public if they would vote for him. We got a wide variety of responses. Then one day, we were passing by the Stock Exchange and Micheal Moore was shooting an illegal music video with Rage Against the Machine, and they saw me with my sign and were like, ‘Dude, come here!’ So, I’m in that music video—"Sleep Now in the Fire." It’s actually kind of a meme on the internet. So, I predicted the Trump presidency with that piece!

Did you ever think it would actually come to pass?

I don’t know. Now, you never know what’s going to happen in the future, right? I mean, no I didn’t.

That’s the thing about the future.

No, I thought it was a joke, you know?

People still think it’s a joke.

It kind of is a joke. It’s scary, though. I like to think that, through my intuition, I was sending out a warning shot, and nobody listened to me. You people don’t listen to me!

So, you’re kind of focused on the future in a way—on looking forward.

Warhol said, ‘We live in the future, we just don’t realize it.’ Consumerist pop culture already is really futuristic. The history of twentieth century art really deals with simulacra—simulated reality, from Duchamp onward, really. That’s the strand of conceptual art, that as society became more industrialized, we would become more artificial, and our view of reality would become more artificial. There are philosophers that I learned about later that were very influential—the most obvious one is Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, a very important piece that was written in 1967. He predicted Instagram and Facebook in the year 1967—the year I was born. So, people understood what was going to happen. Duchamp understood what industrialized society would do, that it would dehumanize us. So, here we live in this shit, and what do you do? I turn to my creativity to keep my humanisms and my spirit up and running and alive.

That’s the thing about the landscape of social media—it’s actually quite internal, and it’s actually not social at all. It’s kind of lonely in reality.

That’s what Debord says—the mediated appearance of social interaction will replace actual social interaction, leaving you feeling more alienated. That’s it, in a nutshell. It’s very important—punks in the '70s and '80s, especially in Europe, they read that, they understood it, it was in their music, it influenced culture when I was a teenager and I didn’t even understand it yet.

It’s always interesting to talk about social media and the way we modify ourselves for it.

We don’t know where it’s going! But yeah, for sure, you gloss over to make yourself look more interesting than you really are. And David Nobody makes himself look more interesting than he really is, probably, to a certain extent—or maybe I defy that, I don’t know. I’m also interested in humans as a complete wreck. We’re animals. I saw a quote from Francis Piccabbia, he said, ‘Man can be understood by his faults.’ This is all the stuff I think about, and I’m playing and having fun, but my work is very serious and there’s no doubt, not to sound arrogant, but I’ve been out to change art since the beginning—I'm definitely out for blood.

'Cheeseface' and 'Coming Apart at the Seems so it Seams.'

So, what will be displayed at the show? Videos of the performances?

There are forty photographs, and I did a special canvas print edition. The photos are usually sold as sets of five, 16x16. And there are only forty released of the hundreds I’ve made, the strongest ones, or the ones I want to be available. There’s a compilation reel of 25 videos. At the opening, we had three performances. I dressed up as ‘Smoke and Mirrors.’ I took a suit and glued little vanity mirrors all over it, and on my face as well. It was really beautiful.

Was that the name of the character?

Yeah, that was the piece. Then I carried a smoke machine with me. It was so cool. I also had a woman painted gold, and later on, some peanut butter involved.

Always peanut butter!

Yeah, those ones that I’m drawn to are comfort foods. There was a lot of anxiety in my family—I don’t want to get into why, it was nothing out of control—but I think me and my sister kind of turned to comfort foods to chill out. Things like American cheese and peanut butter are comfort foods for me. But peanut butter is so cool because it’s cheap, you can put food dye in it and color it, it sticks well to you, you can actually temporarily glue things to yourself, it’s not that hard to get off—if you get it in your hair it’s bad. I wear wigs when I work mainly, so I don’t get shit in my fucking hair, or if I tape things to me I don’t rip what out what little hair I have left on my head.

Anyway, Tiffany Helms was the performer for that. She’s a very talented art model that I’ve worked with a bunch—I love her—she’s contortion-y, she’s unbelievable. I just look at her and think, ‘God, what was I doing when I was 24? Not this.’ She travels the world and models everywhere.

'Plate Techtonics of the Mind' and 'Pill Person.'

Kids these days.

Some of them! They’re really ballin’ on the internet, and they're really creative. A lot of people aren’t, though, too.

You’ve got to seize it.

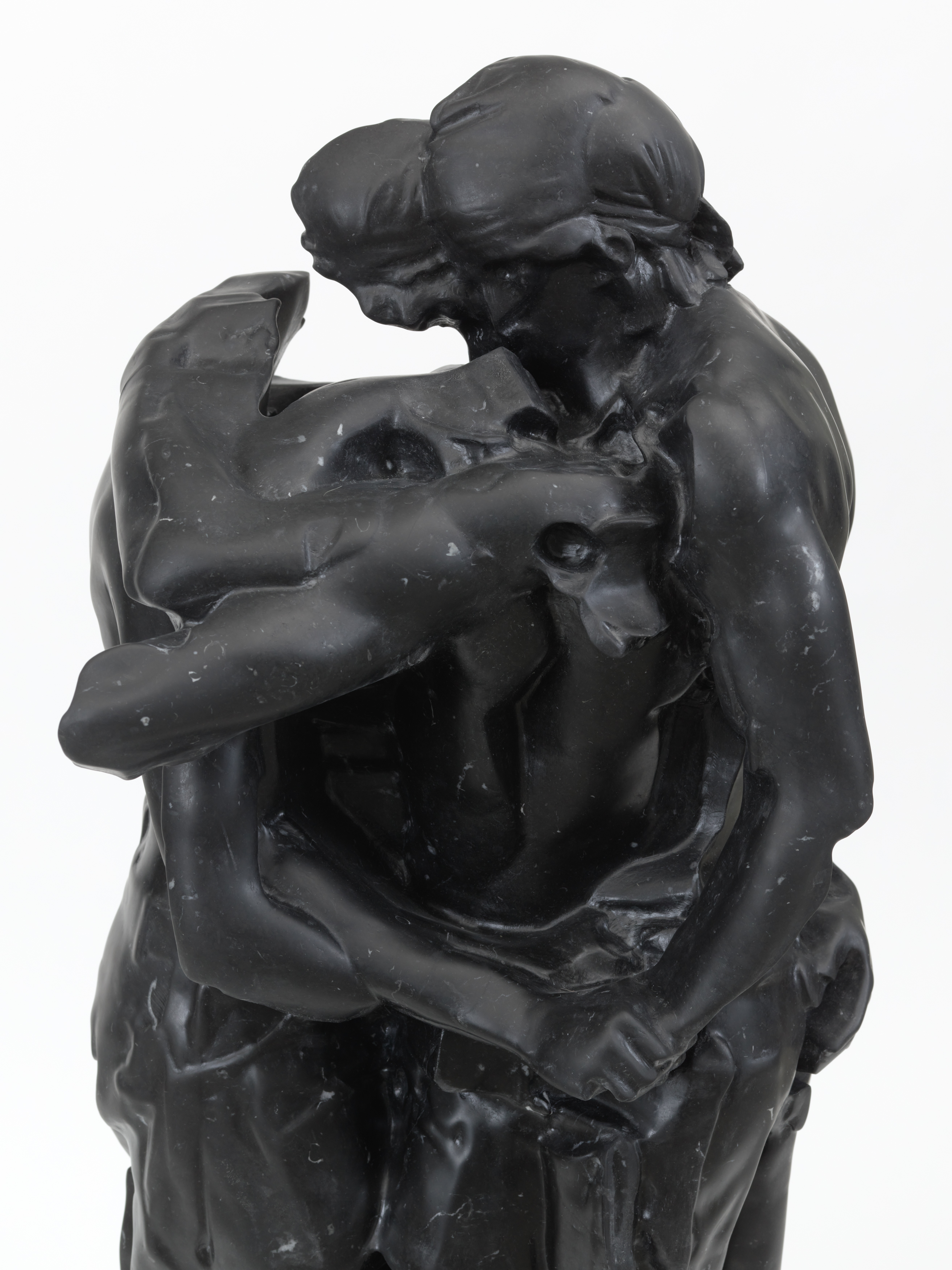

Yeah, I think with social media, it’s really excellent if you’re a kind of creative producer. I don’t have to wait for a museum or a curator to really like me. I can go around anyone now. It’s really empowering. I wish I had this a long time ago. So, Tiffany was this golden woman, in her undies only, and she was on a pedestal high up, arched over backwards and also in different positions, and I had her moving around. She was pretty high up, around six feet up—she was originally supposed to be suspended from the ceiling, which didn’t work out, but it’s based on a Louise Bourgeois piece with a golden figure arched over backwards called ‘Arch of Hysteria’—wow, what a title. So, I wanted to make a living ‘Arch of Hysteria.’ That was really cool. She performed for three hours up there, with only a couple breaks.

Then I also brought in this other performer, this woman Masha, and she’s a professional face painter. I had her do gestural face painting on anybody who wanted their face painted, to kind of animate the audience a little bit—to make them to feel like they were part of the artwork. For a lot of work recently, I really covered myself in a lot of food, it’s kind of like splooshing—I’m definitely fascinated with splooshing, by the way.

What is splooshing?

That’s when people like to have sex covered in food, basically. It’s a fetish, of course. I mean the sexualization of food is really interesting, it’s fun, and it looks really bizarre. So, I’ve been covering myself with food a lot, and for this one, I decided to change it up a little bit. I did that for the last four or five shows—I just always have to keep changing.

'Fake Smears and Facial Food Fiascos' is on view at Contra Gallery through February 15.

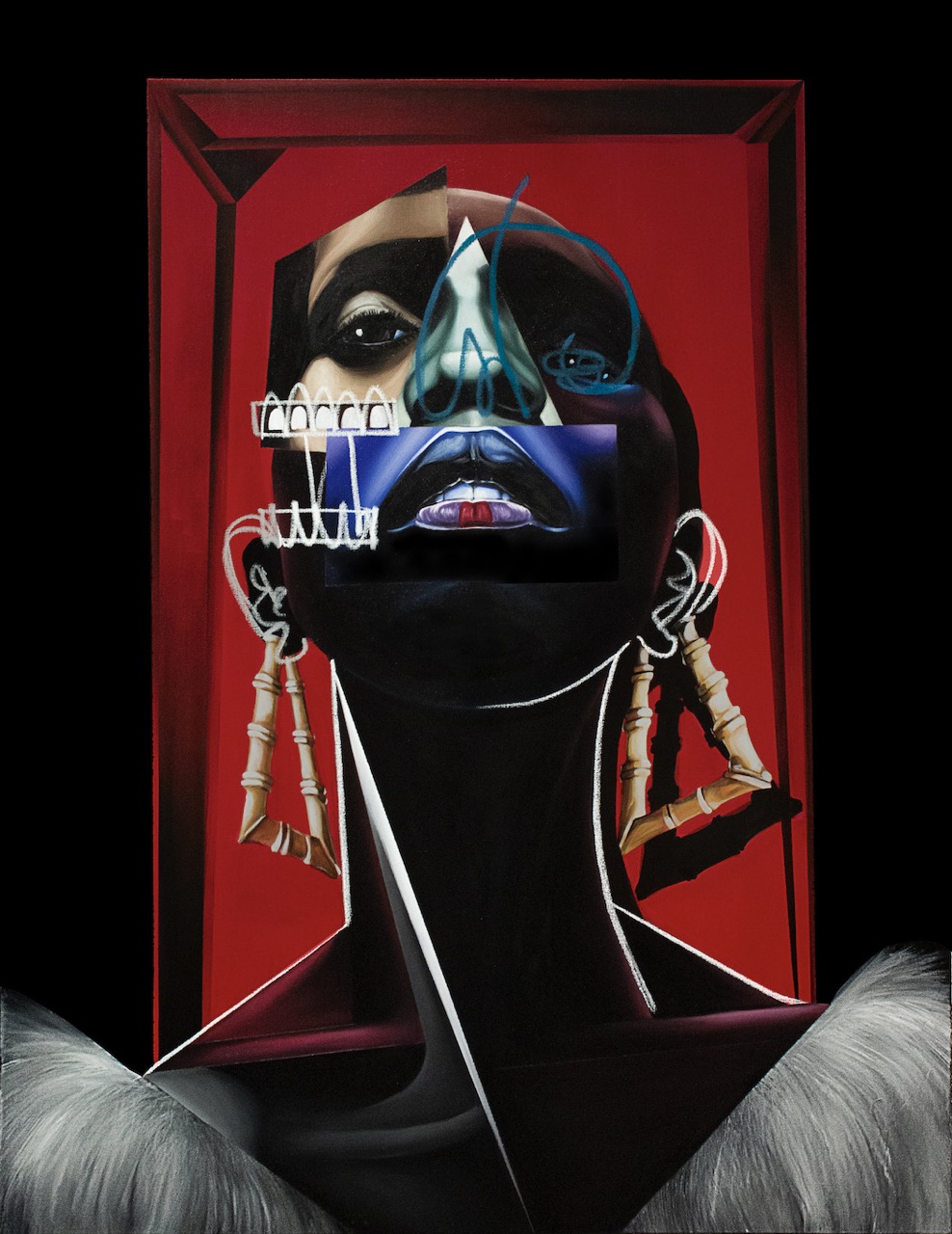

Lead image: 'Fragmenting Head in the Red.' All images courtesy the gallery.