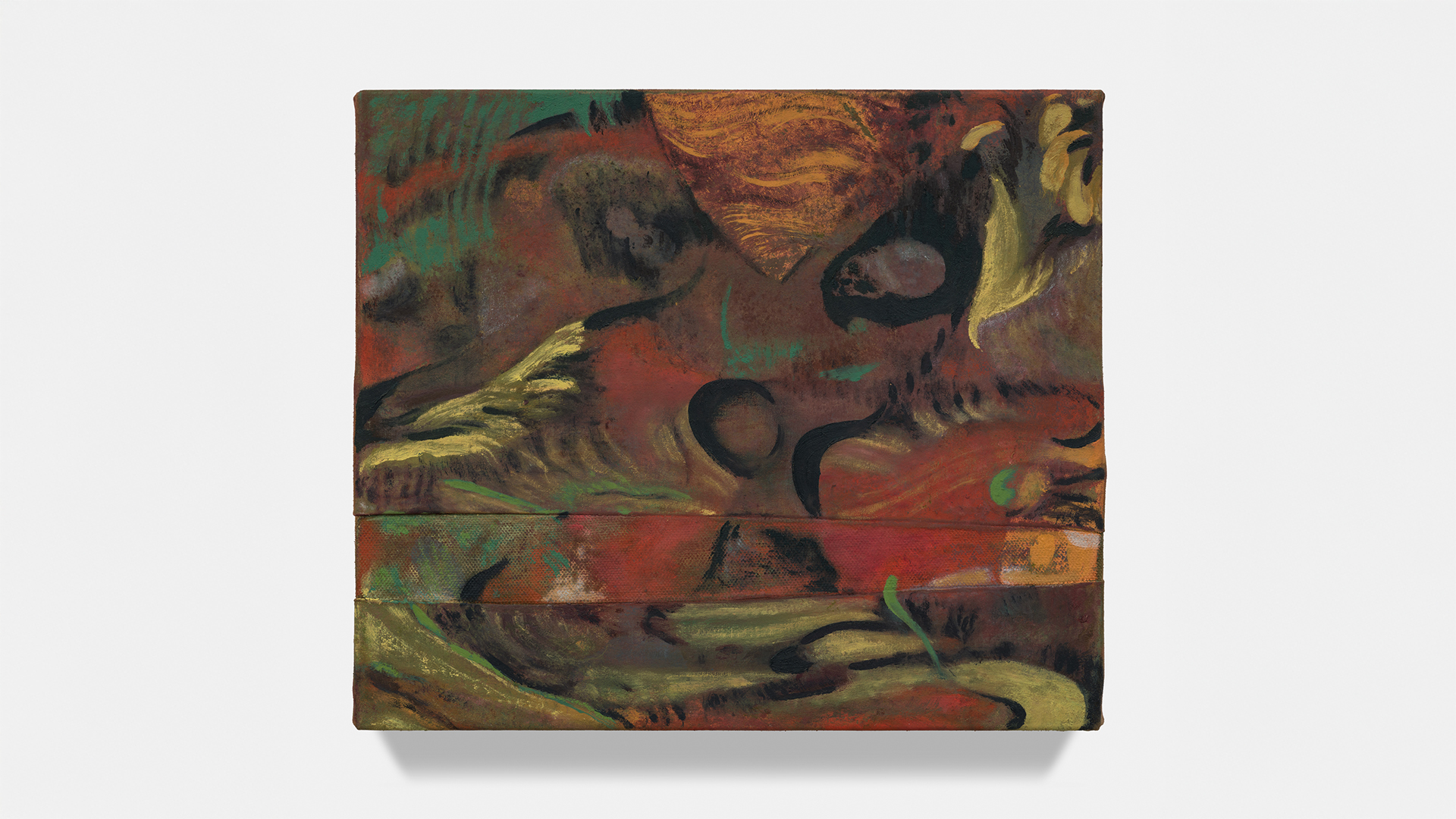

Landscape / Mindscape

What world lies on the other side? office spoke with Theodora to find out.

I love that the exhibition title is an anagram—it’s so cool. How did you come up with that?

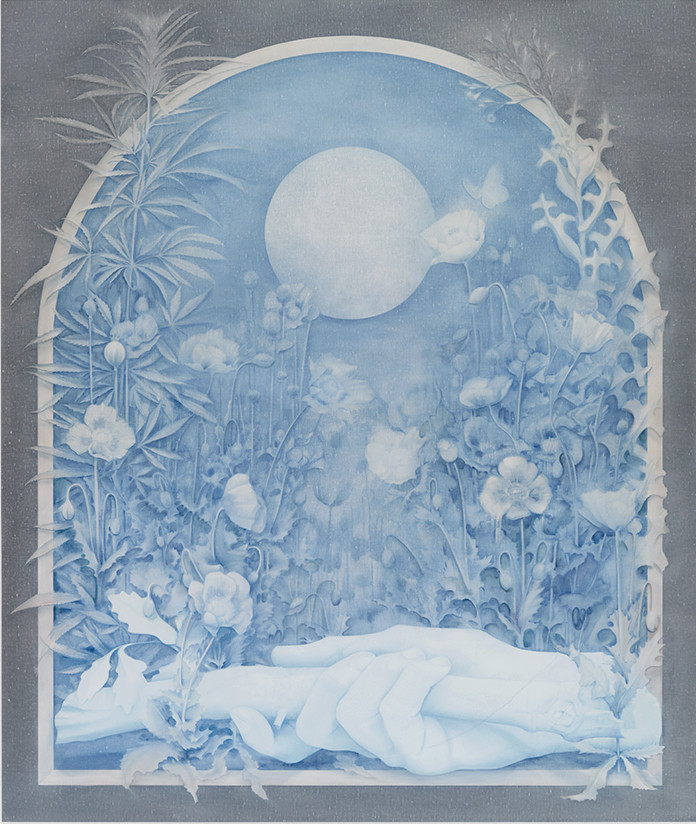

In doing research for these paintings, which involved looking into the histories of various psychoactive and medicinal plants, I came across the term dwale—an Old Norse word that translates to 'trance' or 'sleep.' Dwale, also the given name for a widely used anesthetic in the middle ages; a heady tincture comprised of various narcotic herbage. Through dwale, I came across the anagram weald—another archaic term, this one from the Old English meaning 'forest.' With weald and dwale, and the linguistic play between them, we have two words that locate the imagery in the show to a misty space, somewhere at the cross section of landscape and mindscape.

There is something very Medieval about the pictures—do you have any favorite hits from Medieval or Renaissance art?

I’m endlessly inspired by the stained glass windows and woven tapestries of the Medieval period. The Unicorn Tapestries at the Cloisters are among my favorites.

I’m a fan of the Tarot card-like imagery—do you read cards? Have you ever visited a psychic?

The emblems in the Monument (weald) paintings are based on a suite of symbols from early Tarot card games from the middle ages— the cup, coin, branch, and sword—motifs that have historically stood for the various planes and experiences of earthly existence, essentially what is known as the human condition. My interest in these symbols is rooted in an inquiry that is decidedly humanist, but the avenues that we take to define and discover meaning and purpose in life are endlessly fascinating to me, and for some that includes divination. I’m interested in these histories, but I don’t personally subscribe to any such mystical belief system. I believe in the transcendent power of art.

Do you grow any plants or herbs? What kind of power do plants have over humans? How do you channel this power?

I do have an area on my hillside where I’ve cultivated a few of the plants that appear in this body of work. Most of the imagery of the Jimsonweed were gleaned from this source. The Jimsonweed plant is ubiquitous in Los Angeles—they grow wild and widespread, cropping up in wastelands and off of freeway on-ramps. In the spring, they populate the Arroyo River path near my home and studio in Pasadena, where I often walk in the evenings. From there, I borrowed a few seeds and planted them on my hillside. All of the plants in these paintings belong to a world of remedies, poisons, sacraments and aphrodesiacs that alter, enhance, or destabilize the human experience in one way or another—for better or worse.

There is a lovely sense of restraint in your work—what would happen if you totally let go?

My painting process is slow and precise. The light source in the work comes from the white ground (the gesso), so there’s a certain amount of preservation that takes place in order to maintain that purity and glow from underneath. That said, I always leave some room in the work for aberration, and for changing course along the way. Sometimes, that happens quite dramatically, and other times those decisions are subtle—faint marks and ghost images visible through the layers; a record of how they were made. If I totally let go... well, there might not be any paintings—they might take a different form entirely.

'weald' is on view at Paul Kasmin through March 9. All images courtesy of the gallery.

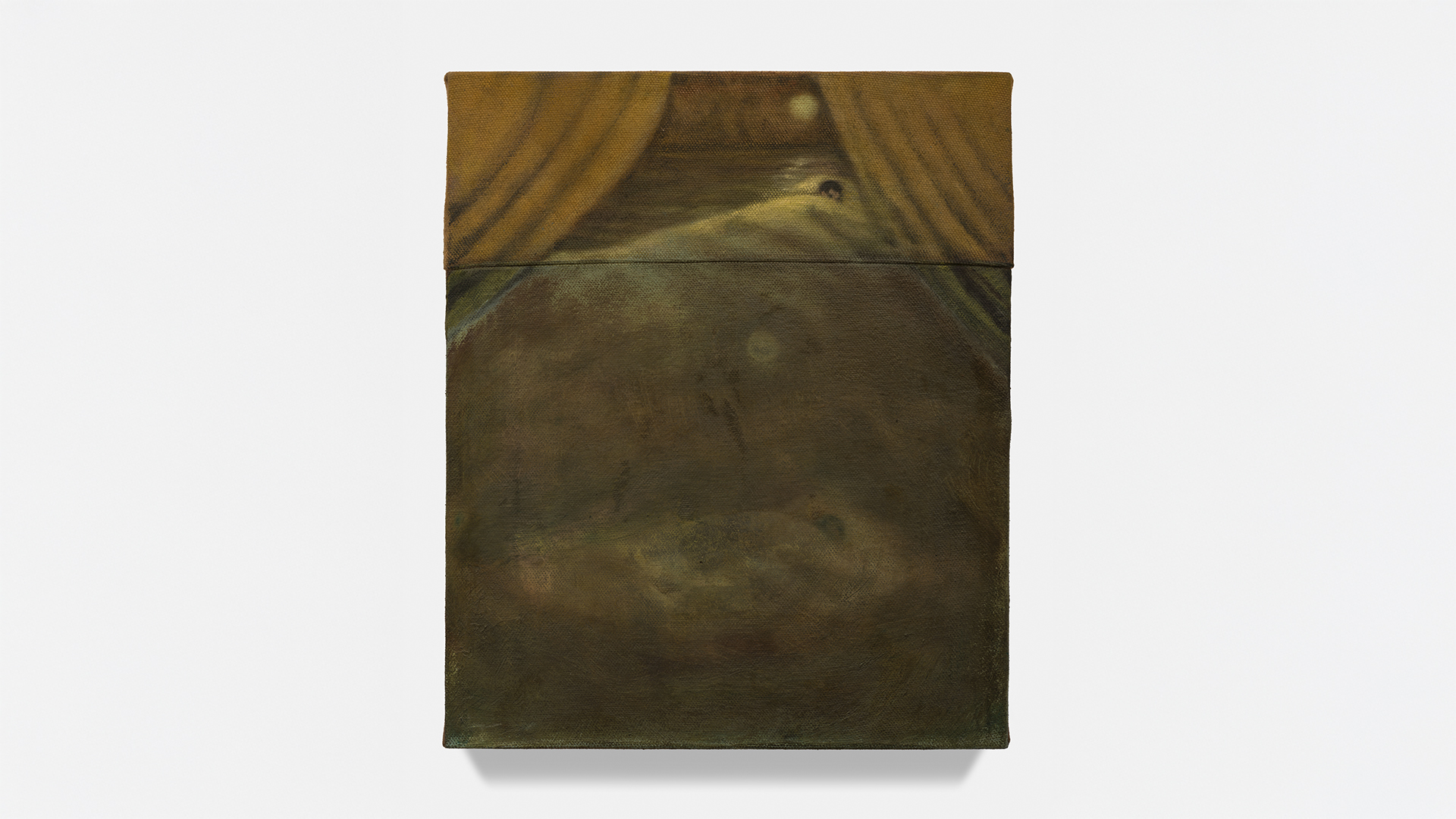

Lead image: 'Monument, No. 2.'