Vouching for Uncertainty

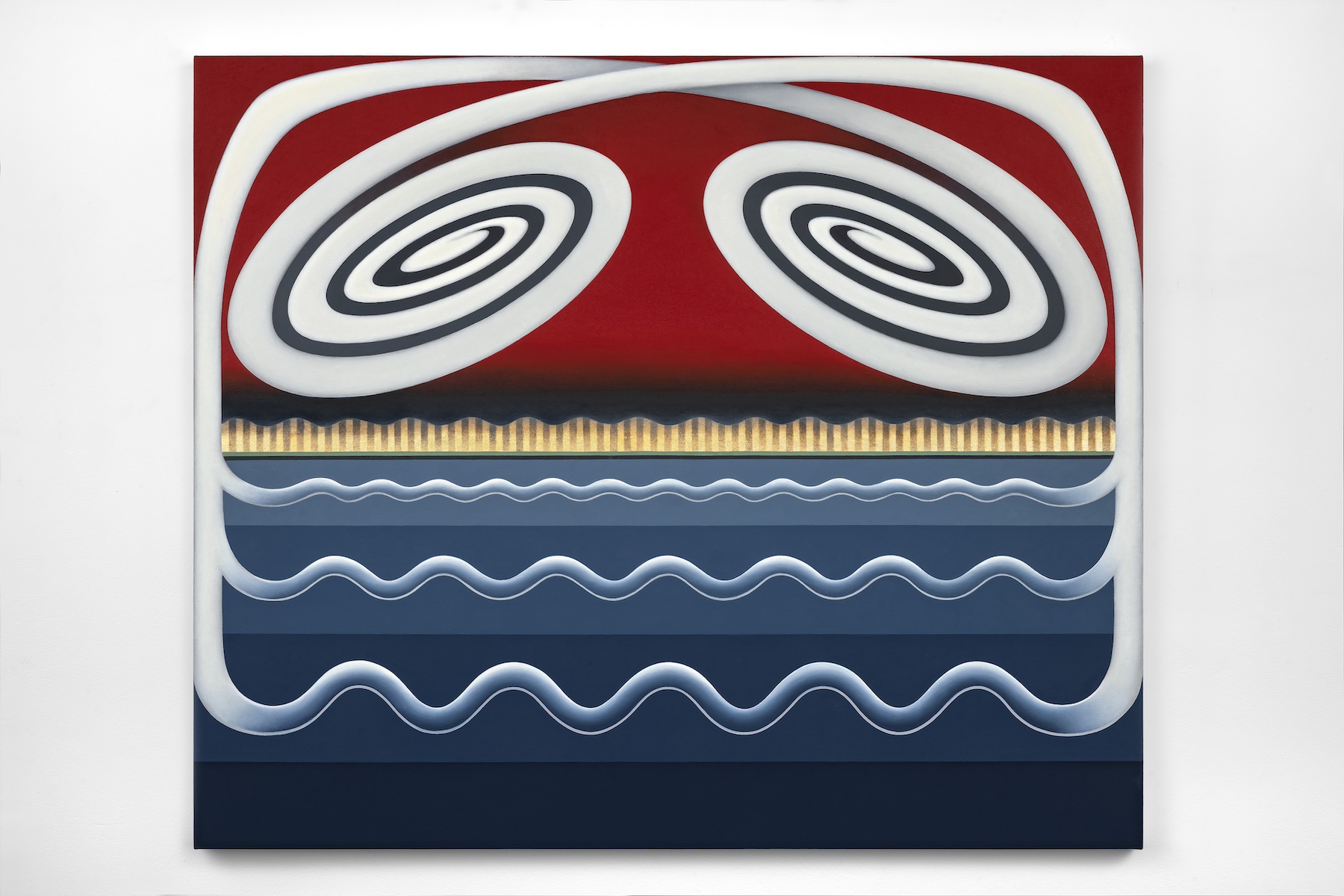

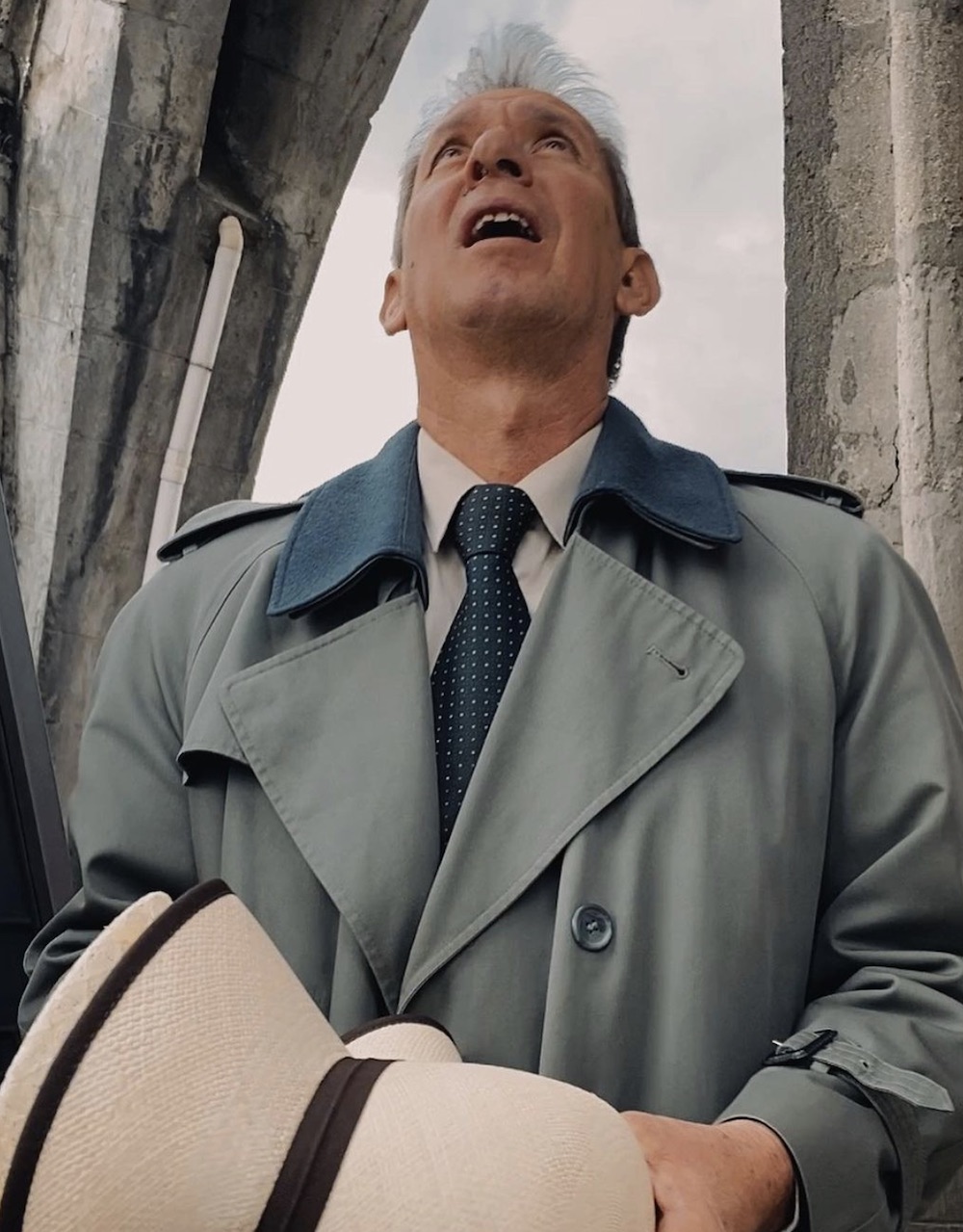

Sitting in the main room of the gallery, Cooke talked to me about his decision to move fully into abstraction, the implications of such, and the conceptual and theoretical reasonings for his new show. Read below for the full interview.

I was doing a bit of research and found an interview you did in 2016 in which the first question was "What is a painting?" You answered that it was a wall of questions, has your answer changed since then?

I suppose it has changed a bit but not a lot. I think the paintings change in order to maintain the questions, so the minute you start answering things, you kind of kill it. I think the idea is to always have new questions. The first principle really is that it has to be impossible, it has to be a range of questions as to what a painting can be, and whether I can do it I suppose — whether it will allow me to have a relationship with it and develop something and move forward. All of that is about questions, because obviously there have been a lot of paintings for thousands of years, and in some way you are trying to find a sort of gap between everything that has already happened, and you aren’t trying to find something that hasn’t been done, but something that is different enough where parts can become infinite — to become a window into something you haven’t really seen before. So there is a newness thing to that.

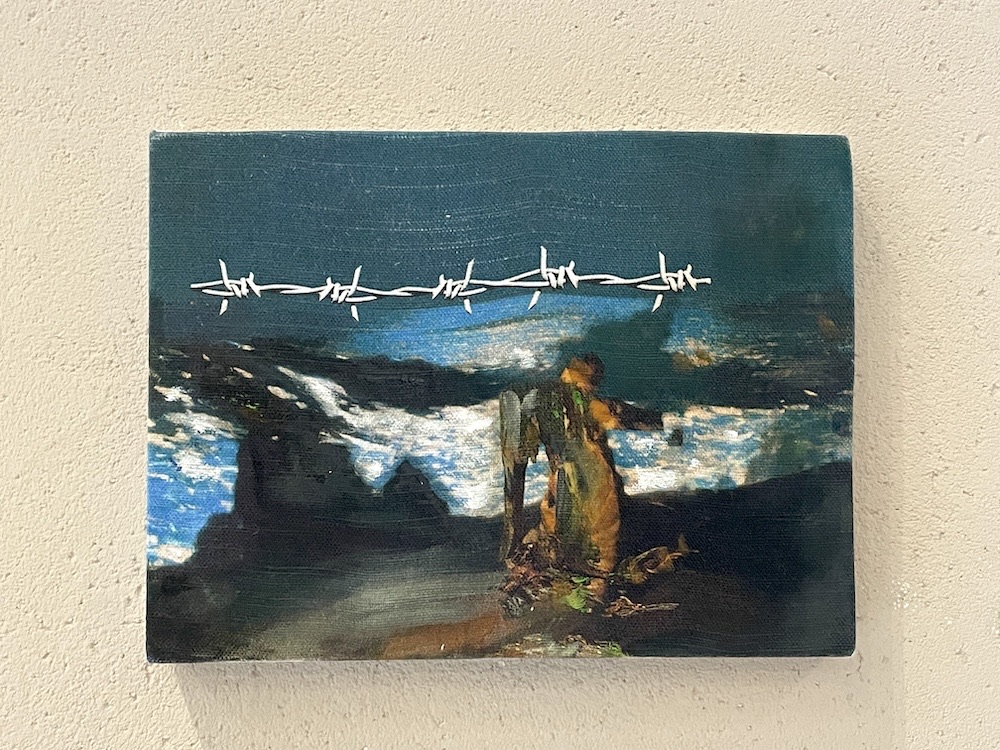

Maybe it becomes more of a wall of questions when there is less of an image. I think that’s changed. I think in a way I’ve exaggerated that question side, I’ve put more into that, because it’s about mystery. I like when I see things that I don’t know what I’m looking at, because I think so many things are geared up towards being understood. Sometimes I feel when the image is too concrete, it can beg an answer that is finite in some way.

That definitely resonates. Your present occupation in abstraction seems to posit questions without giving any explicit answers. It’s nice to hear that this sentiment is a conscious one, in that the form is directly appreciated in tandem with the conceptual side of the work.

I think in a way the word question is about something unresolved, and again something with mystery. Oddly, when I went art school, abstraction and figuration had this sort of interchangeable fashion, I don’t know why it’s still like that, but people seem to say that now everyone is making figural works, or now everyone is making abstract works.

It’s so cyclical.

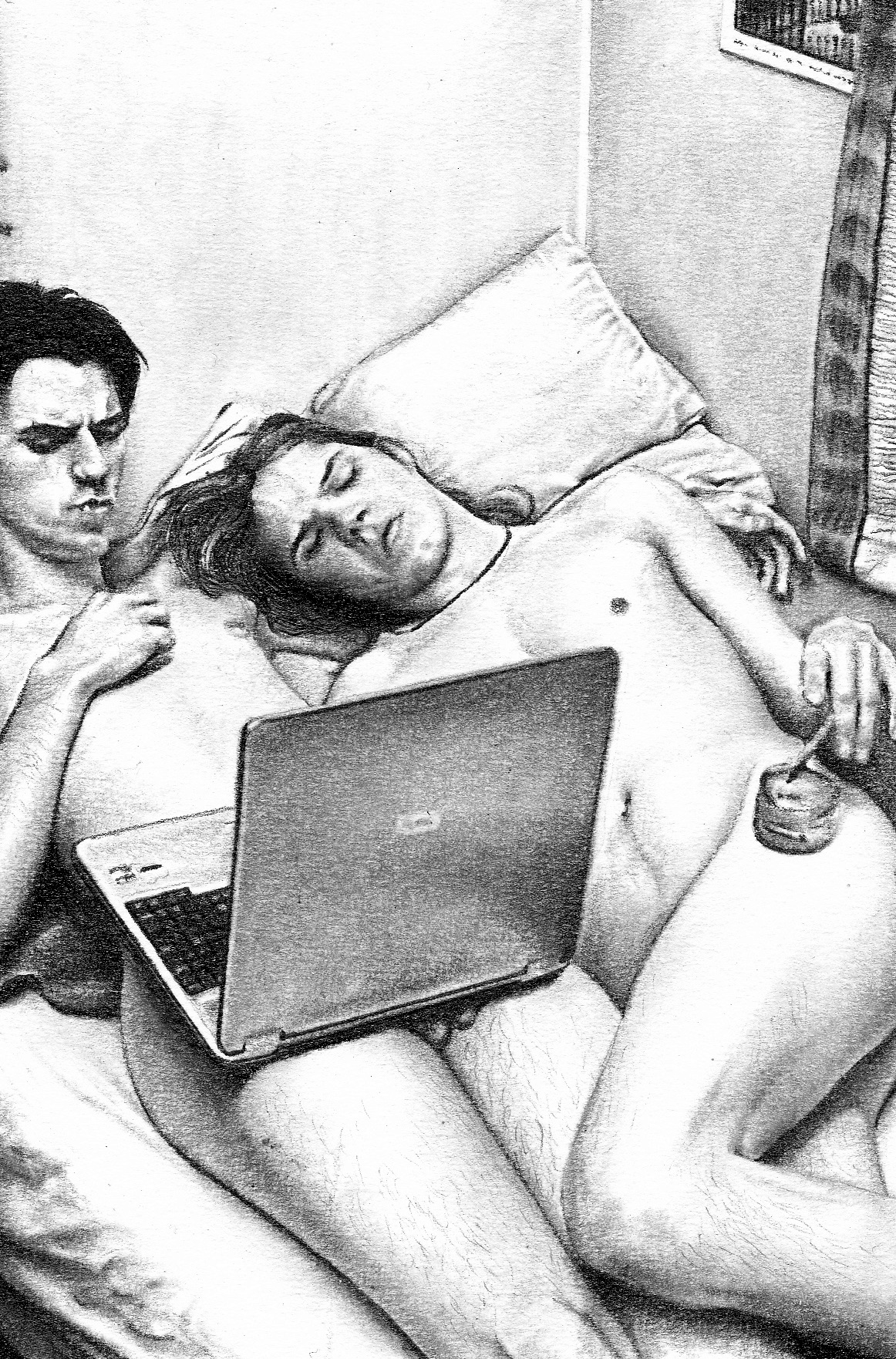

Yes. But for me the abstract painting that I’ve ended up doing is brewed out of figure. It’s not bought into from day one, it was sort of arrived by mistake, almost as a process of adventure. But I think it’s odd if you don’t go through the figures before the abstract. I don’t know why, perhaps it’s a bit too traditional, but I believe you have to nourish abstraction with that kind of knowledge. There’s a lot of abstract painting I see that is too notional — if I put this with this it will equal that. It doesn’t seem very interior, it doesn’t seem arrived at in the process. That’s something I’ve always been looking for, I’m always fascinated by the idea of where it’s gonna all end up, what comes next, and you’re sort of chasing the future in a way, you’re pursuing a painting that’s down the track somewhere.

A horizon amidst the chaos.

Yes. Is it progress or is it just curiosity? I don’t know. Theres always a question of: I wonder if that is possible? From this I might say could there be a monochrome? Is there a way in which the uniform color is an opening shot towards creating a monochrome? And that comes from thinking what is the worst thing you could probably do, what is the most dumb and dead thing you could do. Often times I think those are what gives the most fruitful exchanges, because one, monochromes aren’t British really, so that’s already gonna be odd if I do it. And I suppose this is like that too. In this country, many students have painted like that, much more than in Britain I’d say. But having crept toward it through something else, it’s like putting a different flavor in a meal, it has this sort of conundrum to the combination of things it’s trying to do. In some ways it’s like European figuration, Classical figuration, but then it’s sort of also woven into Joan Mitchell via Manet. In a way the game of painting, with the volume of history, is that there’s always a possibility of bringing your enthusiasms together into a surprising combination that allows you to see something new, which is similar to what I said at the start about seeing the gaps. And its abstraction as a language, reducing and subtracting, rather than the art historical idea of progressing from images. But I think progress doesn’t really exist, certainly in terms of painting. I think it’s for all times.

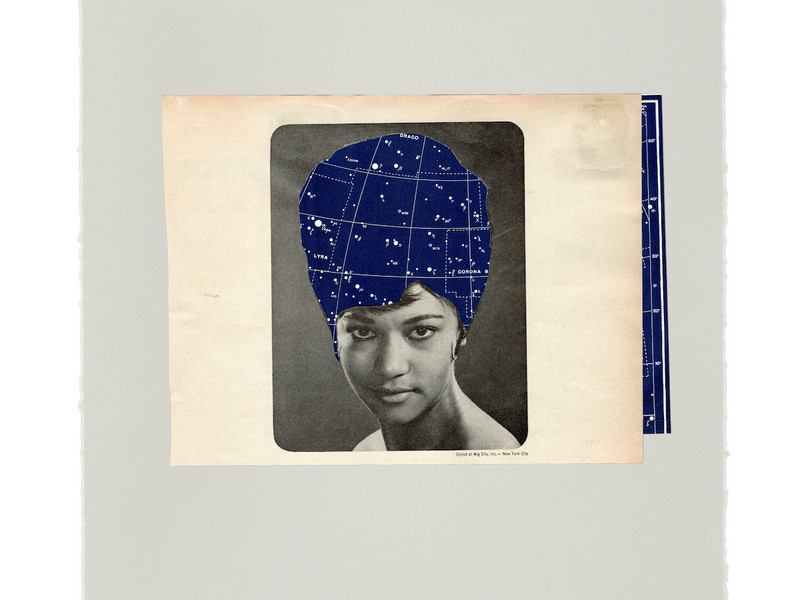

It’s interesting to hear you talk about your works in terms of a genealogy of painting up until this point. To me, trying to digest the breadth of that awe-inspiring history reminds me of the Loren Eiseley essay which inspired your show, in which he chronicles the evolution from mythic notions to the scientific method as two respective means which help us digest and comprehend the awe and phenomena in our world. How did Eiseley’s emphasis on the evolution from mythic to scientific schools of thought — and the essay more generally — inform your work for the show?

I started by liking the title, because it begins with the word “How.” Again it’s about the questions, I could’ve called this show “How," or “How do you make a painting?” Once I dove into the essay, when he was talking about the trend from myth to science, I felt like it mirrored what I was doing. Science is our way of making things more certain around us, and concrete and trade-able as an idea. It’ll say this is why this happens and we all socially understand how science has contributed to our understanding of where we are. But I think that with painting you sort of begin with that, you don’t work towards it, but you begin with that, and it evolves into something that is not made sensible through science — it becomes a private form of mythic thought, in which your reasons why things happen are fictional, and your combination of things can be mythic in terms of hybridized forms, things through time, things influenced by different times and different eras of your own life but also in art history and earth history. So I just liked the idea of working back towards something that was more mythic in the sense that it has in the essay. So one of the things I liked about making these is that they combine things from my own experience that don’t really combine in any other way, a bit like you’re in a life or a thought, a place of flux and incongruent things which only exist for you, until you speak and put them into some sort of order, and the works are the speech. But because it isn’t speech it allows you to join them up how you want, and I think that joining them up into something convincing is like a myth because you want there to be an awe to that. The way I would understand that is thinking about the sublime or nature, where you’re kind of inundated with the volume of it, whether you’re talking about Burke’s sublime or Kant, it’s a complicated and large issue, but what I do know about it is that in a way it’s about the parameters of how you understand something being too big, so you can actually digest and make sensible the thing around you, so there’s a sort of terror involved as well as fascination. And I would say that that’s familiar in this. I’ve sort of set myself into that position because I don’t really rehearse them in any other way. I don’t go into photoshop and cut bits up and put them together, I don’t do collages or drawings. I do little fiddling about things, but when it comes to doing that I’ll look at a bit and take another bit, like listening to music, once it’s come and gone I don’t look at it again, it goes in or it doesn’t, it’s like a moving thing that keeps on going.

I suppose that it’s all about definition, like how am I using the word myth, well I think it would be mystery. And I think that it works when there is some emphatic and convincing way of it being delivered. And I think what I try to do is paint it as though it is an image, with the conviction of having looked at something, but it’s actually based upon having thought something.

There is tremendous intentionality in all of these works, an aspect which I was initially enamored by. I find that your decisiveness helps substantiates the mythical thought map that’s present in the works themselves. How did working in abstraction allow you to explore this sort of myth-making even further, instead of perhaps another genre?

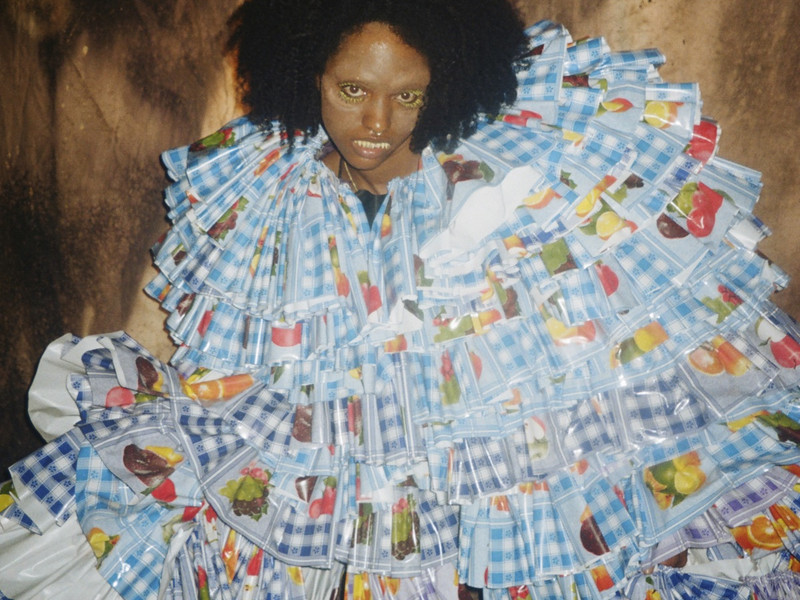

In a way the myth thing is a way of freeing up something prehistoric, or certainly premodern. If you think about the Odyssey, and the idea of the hero before Christianity, you had these figures who were flawed. You could be a hero and be problematic, and that was more realistic, that was more about people relating to something, it wasn’t about divinity, it was about having shortcomings. But also things being transformed to — to make the story work things change form, Athena becomes an owl and then appears in a different form and speaks to him through different parts of the planet at once. There are ways in which you are freed of rules with myth. It’s about telling a story, particularly because most of it is handed down through oral tradition, it’s about keeping something sort of magical I suppose. And I think that when you don’t understand something, you think in a magical way about it. We see this in a negative way with conspiracy theories. People would rather imagine than not know. People don’t say, “I don’t know but that’s interesting that I don’t know,” they just say "I’ll find out and I’ll know.” They’d rather have an opinion than not have a clue, and I think that’s a really dangerous thing. I think in some ways that’s why abstraction became meaningful for me — it’s everything about this knowing thing, this clarity. I just feel in our culture now it’s the most mistrustful and dangerous thing in a sense. It doesn’t allow for changes of mind, or education, or flexibility, or empathy. It’s all about colonizing something, and appropriating it for your own needs. I’m not saying that’s what figuration is, but I think having unequivocal imagery is playing into the least interesting thing about visual culture today, and I think that even if people have got no idea what they’re looking at, and this is common, I still think there needs to be things like that, particularly in art. And I think that in abstraction I suppose I was trying to find a way for it to be magical, you know?

Completely. That dilemma definitely justifies this process you’re speaking of which aims to incentivize an acceptance of uncertainty. However, the marriage of the two — conceptual uncertainty and formal uncertainty — allows for the works to not just exist in that realm of questioning, but also as something that’s visually intriguing and exciting.

That’s really important too, and maybe it has to do with the art you encounter when you are young. But it’s about life, and I mean life in terms of anything that raises your pulse and makes you feel like it’s worth being here. I think it has to feel like a living thing, not a fake picture of a living thing, and I think it’s a bit like Cézanne in a way. He went from pictures which were sort of intellectual as in they spoke to the conscious mind, and into process which actually was about so much more than what he could see. It was about “how do I make marks that are about my relationship to that?” Which became almost about his whole life, about his entire relationship to the world. And I think that in a way through the language, the touch, and the handling of the thing, he kind of allowed modernism to happen because the medium becomes the message. But now I’m thinking in a way that it has sort of entered a psychological era where mental health, inner lives, inner identity has contributed to a different idea about that now. If you think about the Abstract Expressionists in this city, psychoanalysis was really just appearing then, but we know more about the mind now. Since Abstract Expressionism, the science of the mind is unrecognizably advanced, and maybe, in a way, my approach to abstraction is about reflecting that, because it is all interior, it’s all about the mind I suppose, and about how the mind and the outer world are this sort of connection mesh-work, and that you as the person are a conduit between the two. I don’t think I’d be thinking that if the science of the mind generally hadn’t come to where it has. And also how that has affected everyone socially. Now you can talk about mass psychological progress with Covid and whatever else.Various things we’ve gone through, even in the last ten years, have made us feel more alert to what it might be like to be someone else, which is a kind of empathy about the fact that you’re in a life. I think that really fuels the abstraction part.