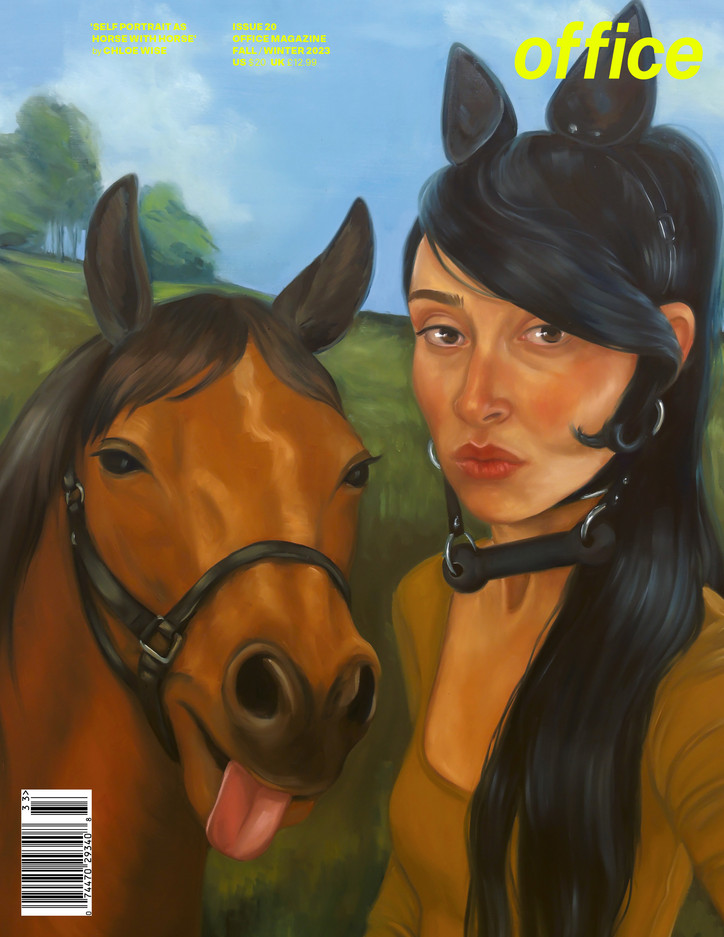

Becoming-Animal: Chloe Wise

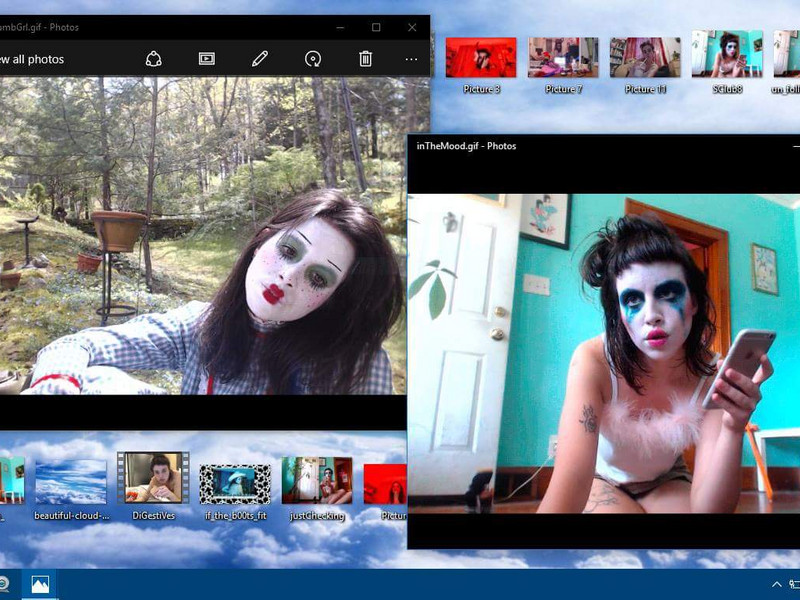

Olivia Kan-Sperling— With poses and faces, people still do this [taking selfie from above] and this [mimics mirror selfie], but —

Chloe Wise— Yeah, we do them differently now. Back then, you didn’t look up into the camera; you looked down. Maybe because displaying your bangs — your scene haircut — was important, so you wanted to capture the crown of the head. Also, because this was the time of skinny jeans, it was about making your legs look little.

OKS— There was also the one, which hasn't come back, where your phone is lower and you're leaning in —

CW— You're leaning in, so your legs go further back, emphasizing a thigh gap. And you’re either doing a peace sign or you’re holding up your hands in confusion, like, “What? Who? Me? Why?" It was performative “awkward.”

OKS— Also squeezing your tits together. No one does that any more. Anyways, it’s interesting that there’s so much overlap between the faces you’re making in these photos and the expressions of the models in Natural Causes.

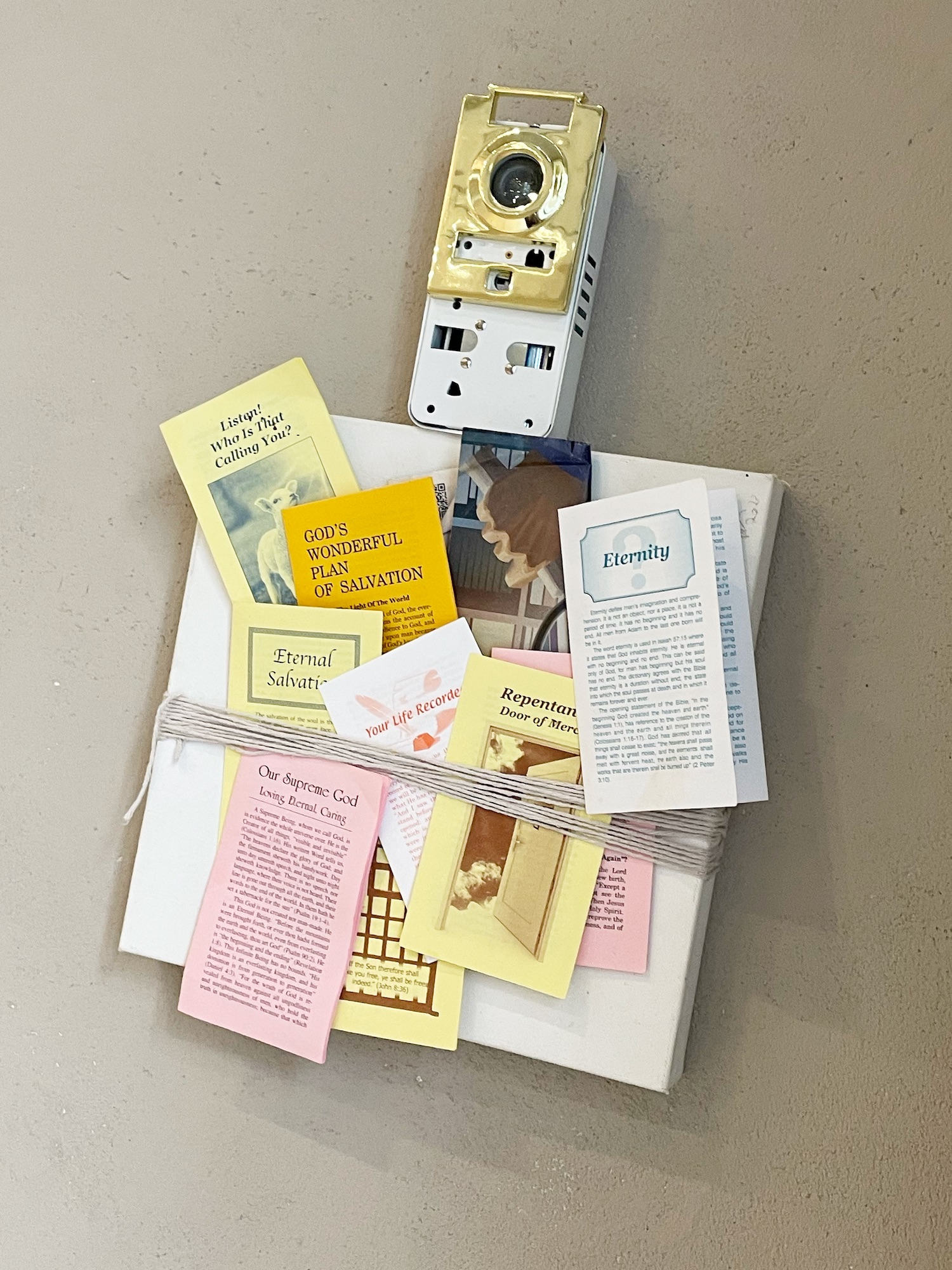

CW— Actually, when I started working on this show, I was scared it was going to cross into the territory of antlers, twee bands, “awkward” culture, mustaches, feathers in your hair — which is what I was giving, back then, as you can see. Every indie music video had an animal head on a guy with a suit.

OKS— Indie animals were specific types of animals, though. Wild animals. Quirky, authentic animals.

CW— North American animals, particularly: fox, deer, bear, owl.

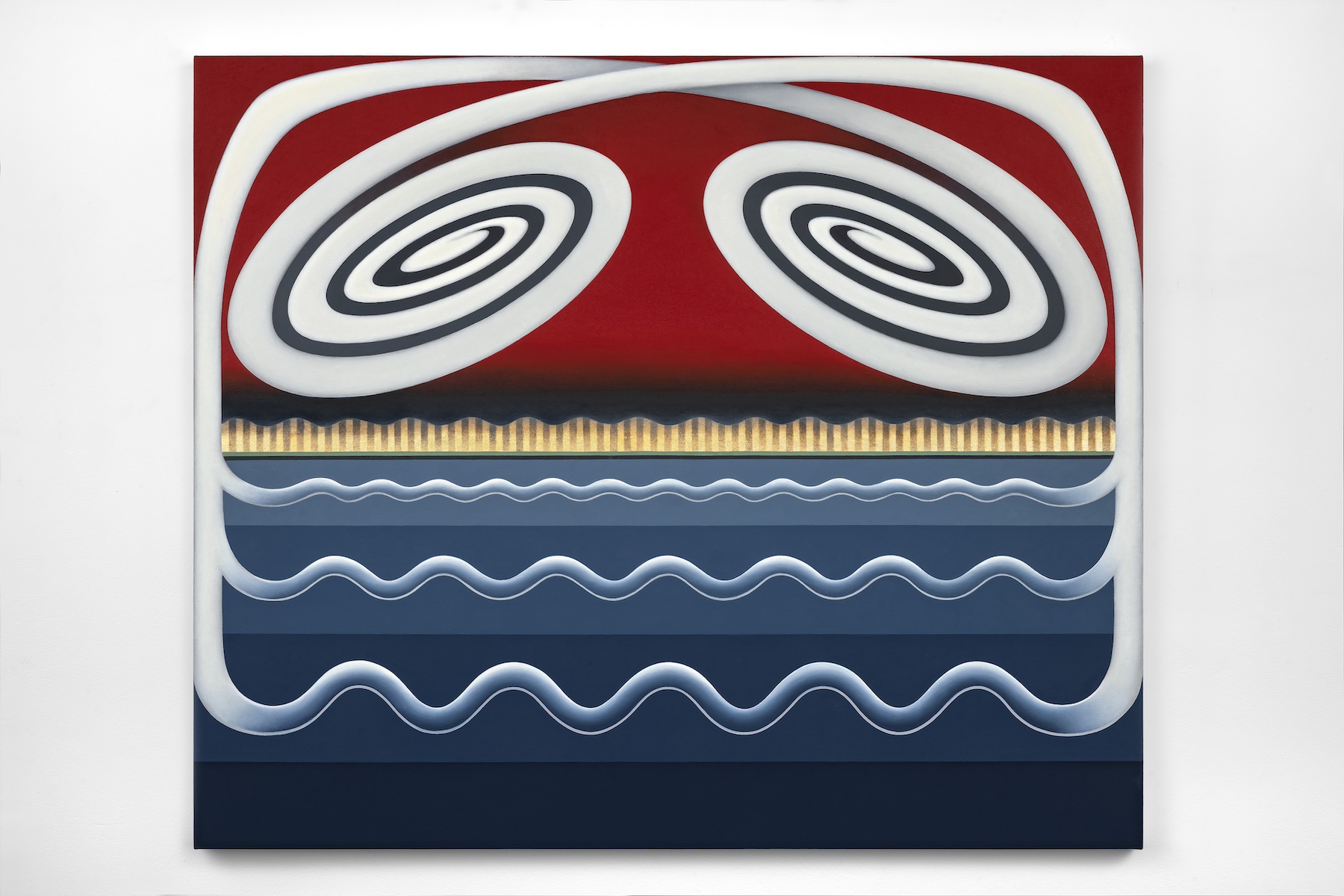

OKS— The animals in this show are more generic zoo and farm animals: pig, elephant, dog, toucan.

CW— Right. With this show, I wanted to approach a more timeless aesthetic. The stock photos of the kids that I painted are from the 90s, which feels like the aesthetic period we’re more or less still living in.

OKS— At the same time, the adult faces here do remind me of a specific moment in millennial body language history. Maybe a Cobra Snake party photo. These expressions are very different from a Zoomer e-girl bad-mood selfie with a bratty pout. These are people “having fun.” They’re “Party Animals.”

CW— Exactly; they’re consciously representing having fun. These paintings never captured anything real other than the photos we staged in order to become paintings. For example, your smile in these paintings is very much a smile that is aware of itself, not the kind of smile that you break into naturally — like a yawn or a laugh or a hiccup — that takes control of the face for a quick moment, that is fleeting. This is the kind smile that stays, that you count down for, that remains past the point of being what it is.

OKS— What draws you to painting faces?

CW— I don't know what came first, being a portrait painter or being obsessed with faces. I’ve always been obsessed with faces. Maybe that's why I paint. But it’s also that, because I paint, I'm obsessed with faces. The face can express so much, so quickly, with so much more nuance than words can. When somebody consciously puts on a facial expression — tries to look like they're listening, for example — we can read that instantaneously. When you play with kids, the first thing you do is put your tongue out, make a funny face. The human face contains millions of functions, millions of muscles and possibilities. It’s been around much longer than language.

OKS— That’s what’s interesting to me about Natural Causes: you literally put the animal, the pre-linguistic, back into the human face. At the same time, you show that even non-verbal communication is always culturally determined, self-conscious, or unnatural: a type of language. Just like how the words we have for animal noises — oink, bark — vary across human languages.

CW— Verbal communication is so incomplete; that’s why we have body language. I think we yearn for that complete, continuous, pre-linguistic oneness that animals inhabit. I think we fear and envy them for it.

OKS— Is painting closer, for you, to a more “animal” mode of communication?

CW— Maybe if you asked a gestural abstract painter, they would say yes. But I think my painting is closer to language, not only because it's figurative and quite literal, but also because it uses an alphabet of recognizable facial expressions and types of poses.

OKS— Exactly! It's strange to me that critics often emphasize that you paint people you know. To me, your paintings aren’t primarily portraits of individuals. They're more like depictions of social types or emojis — models in the literal sense of being a model of a society.

CW— Usually, the first time I paint someone, I do want to do them justice, so achieving a likeness is important to me. But that isn’t the point of my painting. It’s not like I'm a hired portrait painter. Since I've let go of trying to represent a subject, I’m able to use them as a form or symbol or embodiment of this abstract combination of gestures and feelings. I paint people I know because that’s who's around. I don't get to tell Heidi Klum — actually, remind me to come back to Heidi Klum dressing up as a worm — to come over and put on a scuba mask and take off her panties.

But it’s also that I'm compelled to paint people that I've looked at in real life — to explore specific colors that are happening in this person's face, or that weird look they gave. I'm sitting here and looking at you and noticing all these tones and reflections, painting you in my head.

OKS— Natural Causes is so much about appearances: managing appearances, knowing you're being seen. I remember hanging out with you when you had just spent the morning deleting every photo of yourself from Instagram. But some of them are back now. Why did you un-make that decision?

CW— Well, occasionally I just have a random lack of confidence, where I look back at my career and regret the fact that, in my case, the art was never separated from the artist. If nobody ever saw me and I wasn't on Instagram in a horse costume, yeah, maybe my work would be taken more seriously. But why should I not be able to be myself and make rigorous work? To be vapid and silly and playful and intelligent? I want to fight for the ability to possess multiple, seemingly dissonant or incompatible qualities. Which includes the desire to post photos of myself online.

OKS— I think that this also gets at one of the paradoxes explored in your show. Real freedom of self-expression is also the freedom to produce a fake or mediated version of yourself. That’s a natural human desire: to play pretend.

CW— Yeah, and who will care about my Instagram when the earth is charred and unlivable? Who will fucking care that I showed how much fun I was having in my Skims outfit? Oh my God — I just bought so much Skims yesterday —

OKS— Wait, yeah, I want to talk about Skims … Is there anything else you want to —

CW— The horse outfit in the cover painting is Skims. I just sewed hair extensions on the ass as a tail. It’s literally a ponytail.

OKS— That was your Halloween costume last year, right?

CW— Yes — which totally relates to the show. Halloween is this amazing ritual where we get to shed our identities, knowing that we’ll come back to them. Humans have always been doing this, whether it's Carnivale or Day of the Dead: creating a moment where the order of things is temporarily reversed. Chaos is produced as a treat so that you can be a more complacent, civilized subject when the clock strikes midnight and you take off your costume.

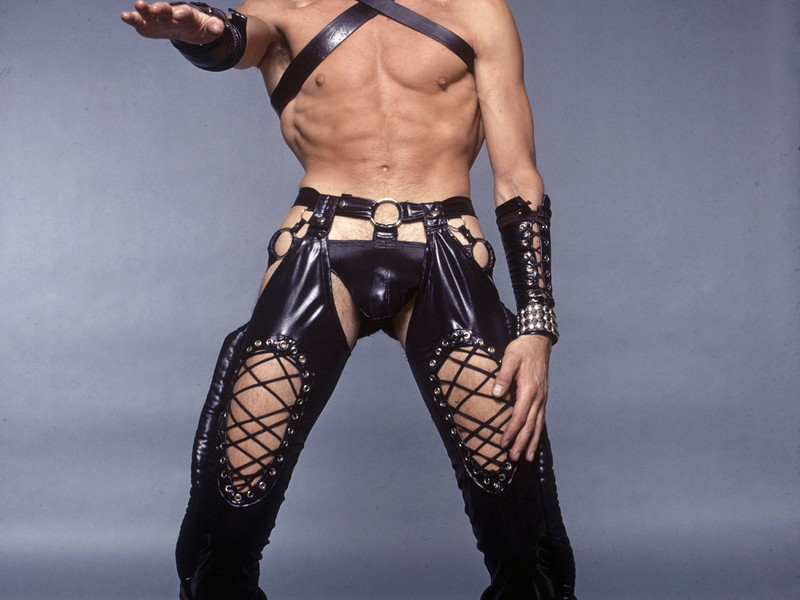

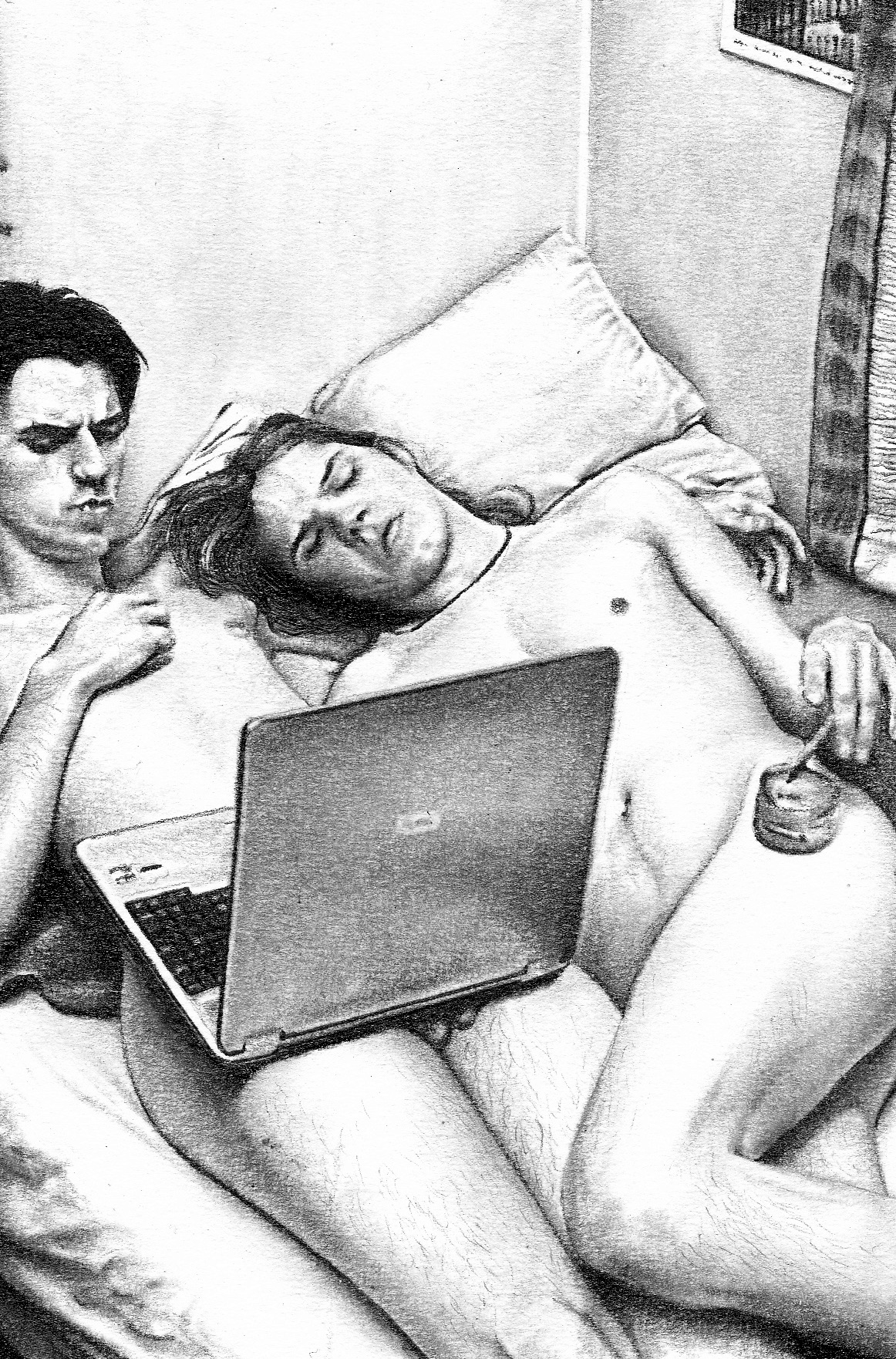

Sex is similar: a type of playtime or role-play or sanctioned discontinuity within daily life. That’s why the adults in these paintings are nude. (Interesting that Halloween, for adults, is about sexy animals.) For most people, BDSM wouldn’t be fun if it were their whole life. It has to be a kind of recess from your standard subjectivity.

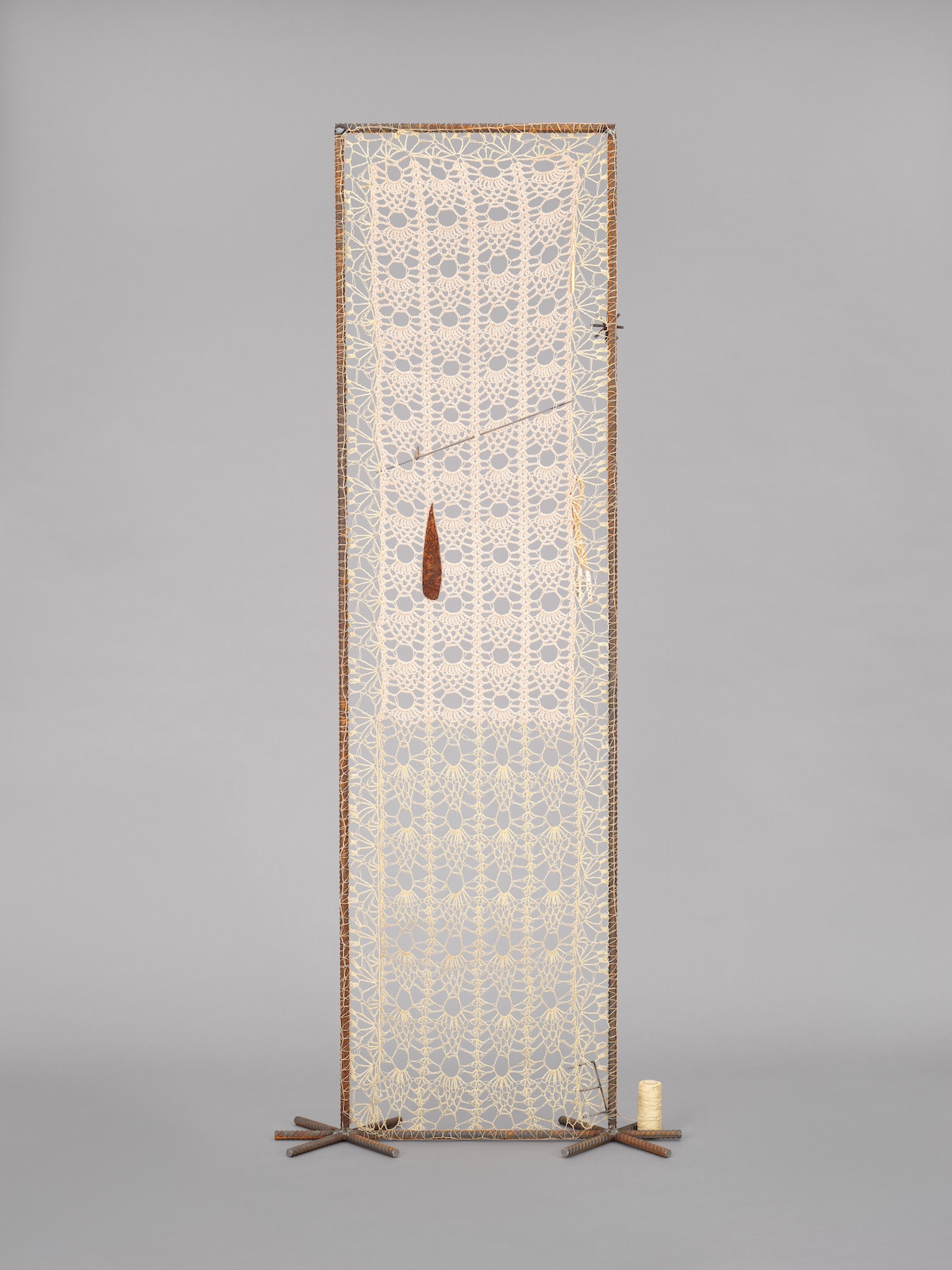

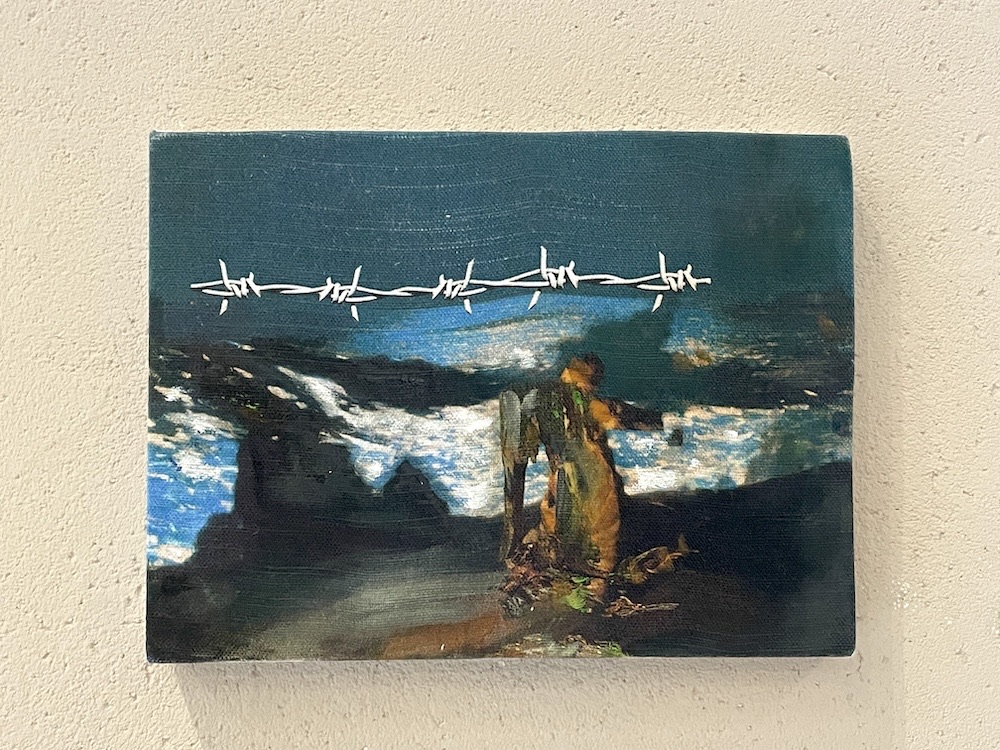

I’ve been interested in Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of becoming-animal. “Becoming,” for them, does not produce an end-result. If becoming-animal were to reach its conclusion, if the human can no longer remove their mask by choice, that’s where horror and violence come in. That’s a werewolf. But when you dress up for fun, it’s the process of becoming-animal that is at play: you’re neither Chloe nor Horse, you’re the third term, you’re “being both” — which is becoming. That’s why I chose to paint these portraits as floating heads, without a background that indicates where these moments are happening. I wanted to show this ambiguous space where you’re literally suspended between worlds. A continuous space. That middle ground is what language cannot describe. And I think that's what art can get to.

Games are also where we get to negotiate realities from our daily lives we couldn’t confront otherwise. I think that we need these rituals on a foundational level. The object of the animal mask reifies the fact that you are not, in fact, an animal. We play as animals in order to be more human. When we do that, we’re also tapping into the kind of pre-individual unity or oneness that animals, for us, represent. On Halloween, we rarely dress up as a specific horse. We dress up as “Horse” — a generic, general category. So we’re not just taking a break from our own individual subjectivity, we’re taking a break from subjectivity, period.

OKS— I think this ties back to selfies and photos in a way: I like taking photos of myself because it introduces a rupture into that continuous present; it’s like a break from consciousness. And it’s funny that people at parties usually feel more free to behave bizarrely if they’re being recorded. The camera is like a mask or alibi: “This is just who I’m pretending to be for TikTok. Of course I wouldn’t randomly do the worm.”

CW— Totally. And speaking of worms — here I can finally get back to Heidi Klum — remember when she dressed up as a worm for Halloween? I should paint that. That costume was amazing because she came too close to actually becoming an animal. She went past the safe sort of playing pretend and into the grotesque. She actually looked like a worm. That, for me, is where art and humor and beauty and real meaning begin.

I go so hard with costumes, too. This year I want to be Dr. Evil. I’m such a theater kid, which is always revealed on Halloween. I even have this monologue memorized. Ready?

“My childhood was quite standard, really. Summers in Rangoon. My mother was a 16-year-old French prostitute named Chloe with webbed feet. My father was ...”