More than Adorned: David Chatt's Solo Show

“In effect, I’m using a layer of beads as a reductive medium rather than an added medium or an embellishment. I’m taking away rather than adding to,” Chatt tells office.

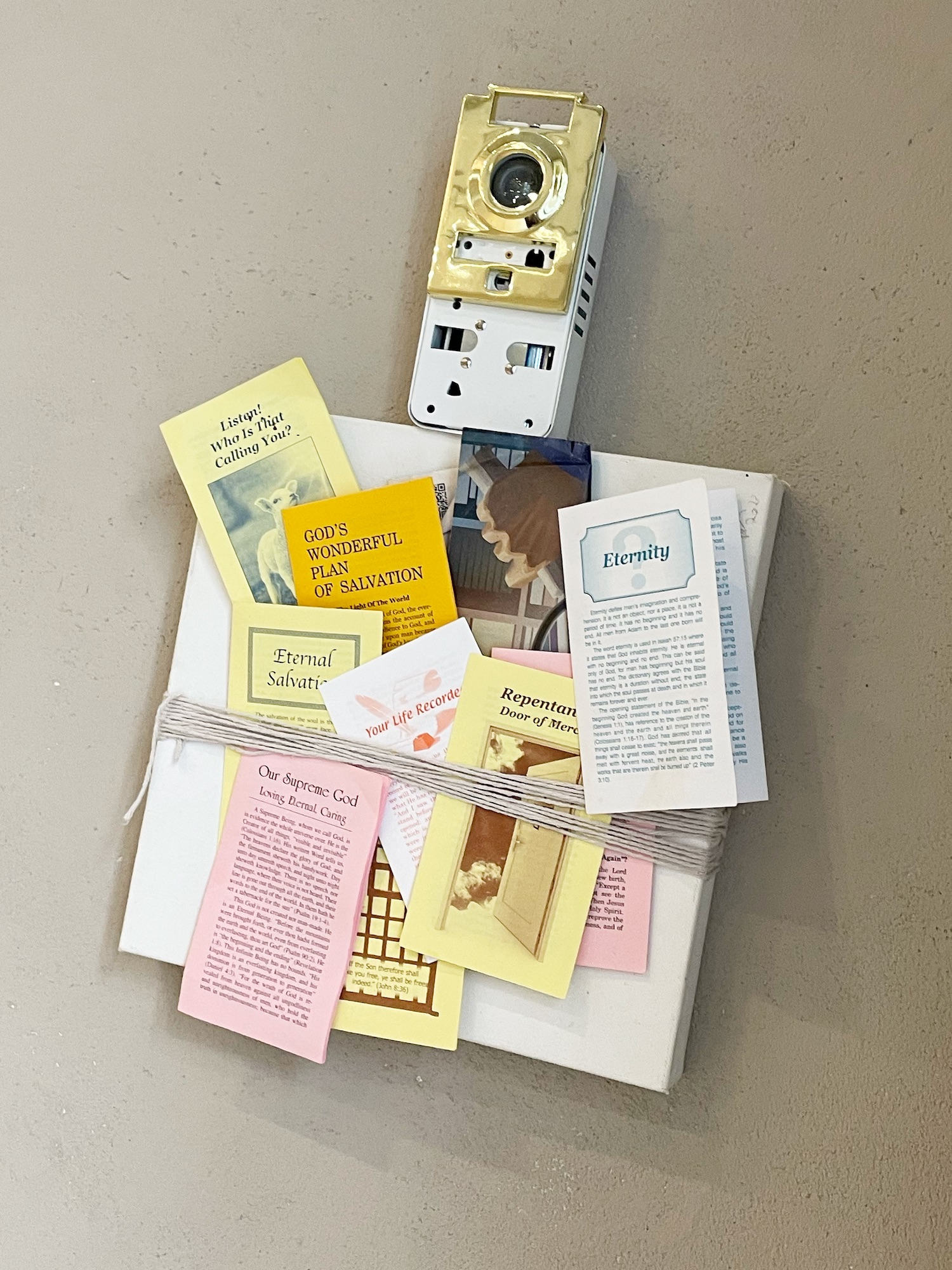

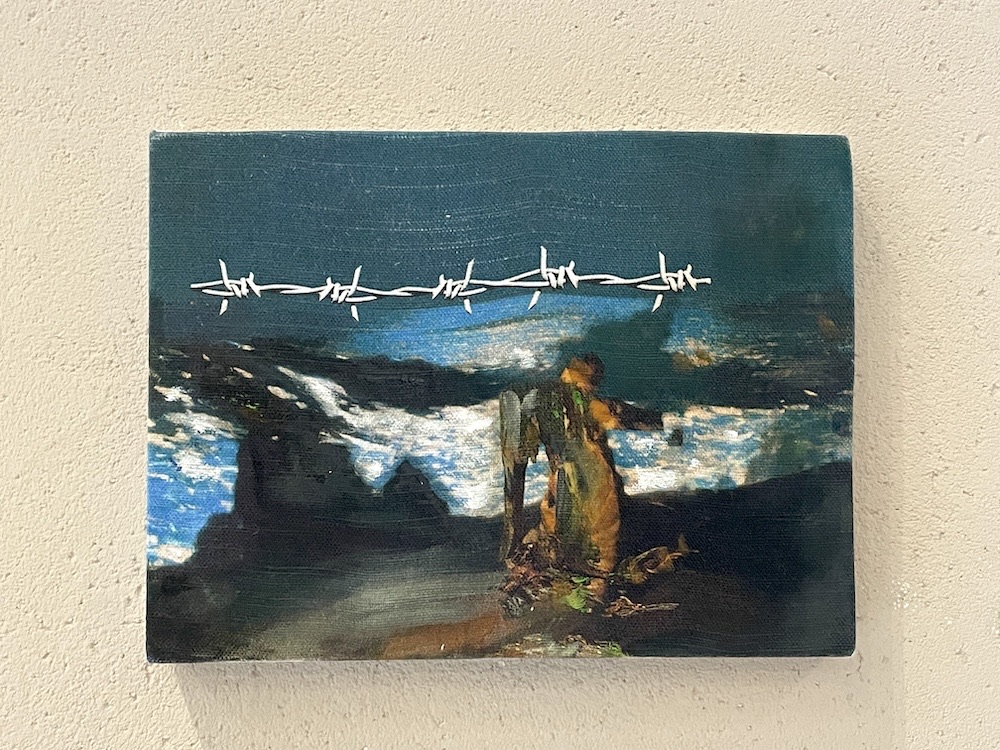

The extremely accomplished, self taught artist's work, Love, Dad, was acquired by the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in October 2020. The pieces in this exhibition, entitled "Scout’s Box" after To Kill a Mockingbird, give us a narrative, sentimental, and nostalgic feel, though it’s not simply that — they have some gumption, tenacity, and mystery. He stops his objects in time, calcifies them in glass beads for us to view as frozen moments.

Check out our conversation below.

What I would love to know first is a little bit about this body of work that you’re showing in your upcoming solo exhibition. If you had to say a little blurb about it, what would that be?

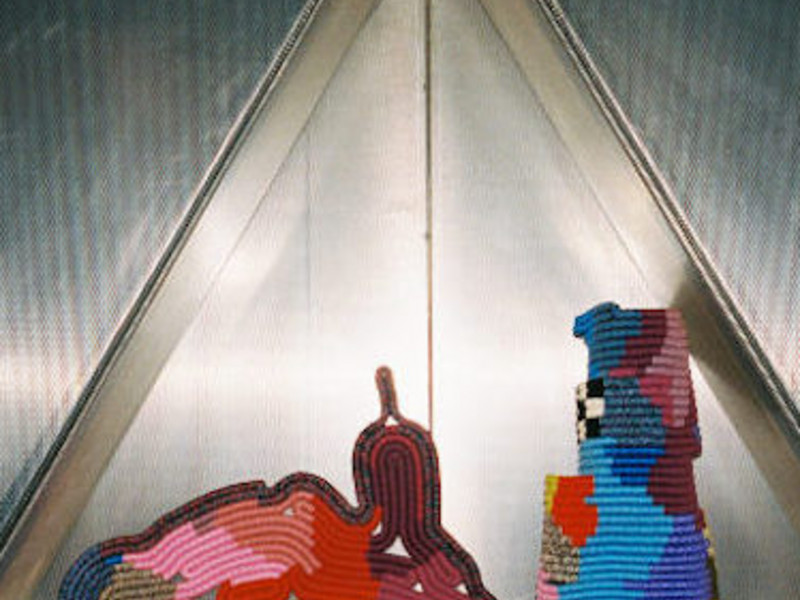

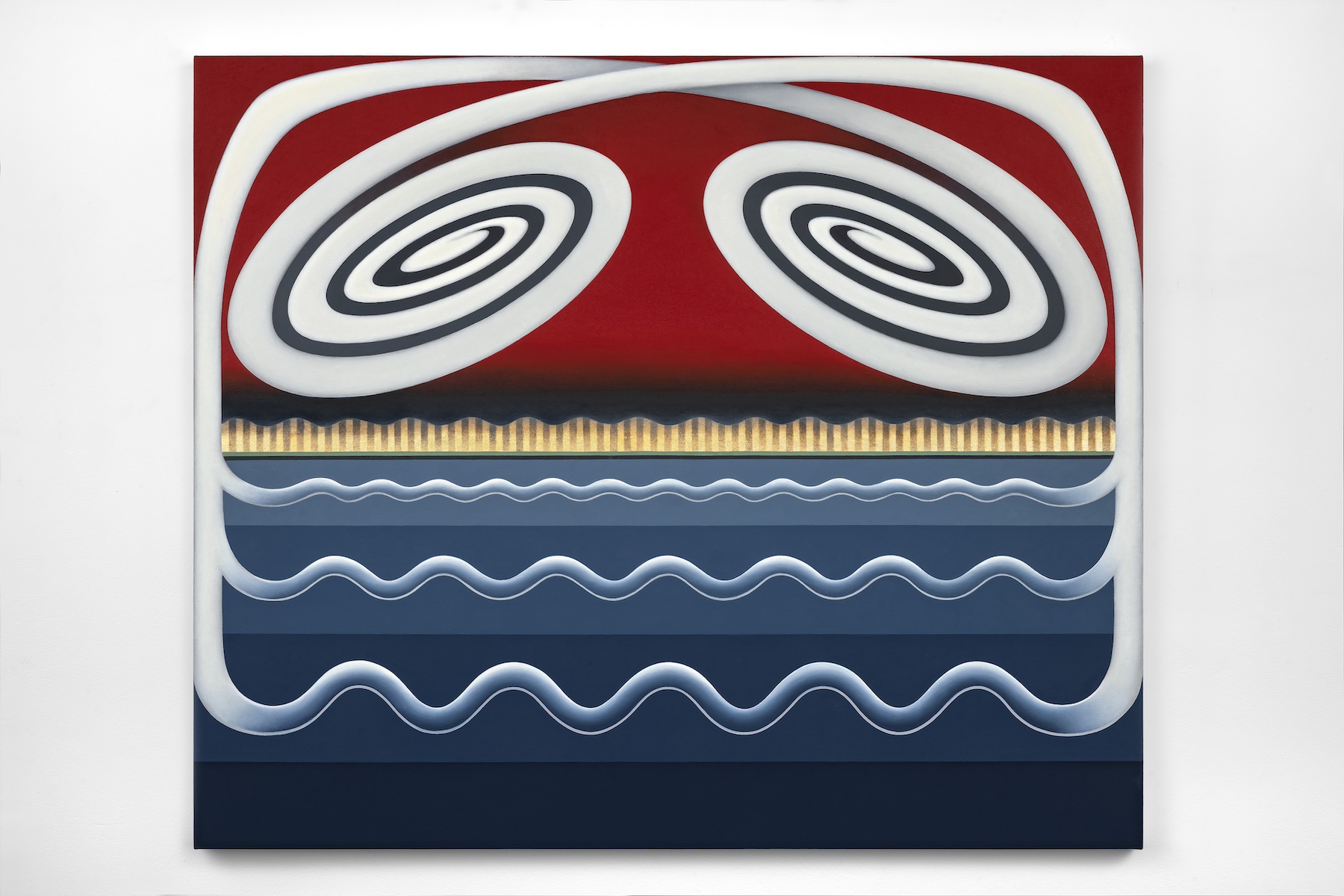

I think it’s a lot about transformation. I don’t wanna say, “I think it is,” it is about transformation. My work, I have a lot of time to think about it as I work. I’ve been doing this for almost 40 years. Early work was decorative, but I’ve had some very distinctive phases in my work, and they’re often challenges that I set before myself. Early work was decorative, and it’s become increasingly more narrative, and telling a story with a medium is interesting to me. Trying to figure out, you know, at first I was just attracted to the medium for all of the obvious reasons that one is attracted to glass and beads. It’s a human experience that is almost as old as humankind. The more I worked with it, the more I wanted to see if I could tell stories. I studied anatomy for a while, and I was doing figurative work. I’ve done a lot of different kinds of narrative work. But one of the interesting things that I’ve found in my career is creativity comes from limitations sometimes, rather than having all the options. I just kept thinking that one of the powerful things about the work is everyone always wants to know how much time it takes. People instinctively understand the work I do does take a lot of time, it’s an unreasonable amount of time; I worked for almost a year on some of my larger pieces.

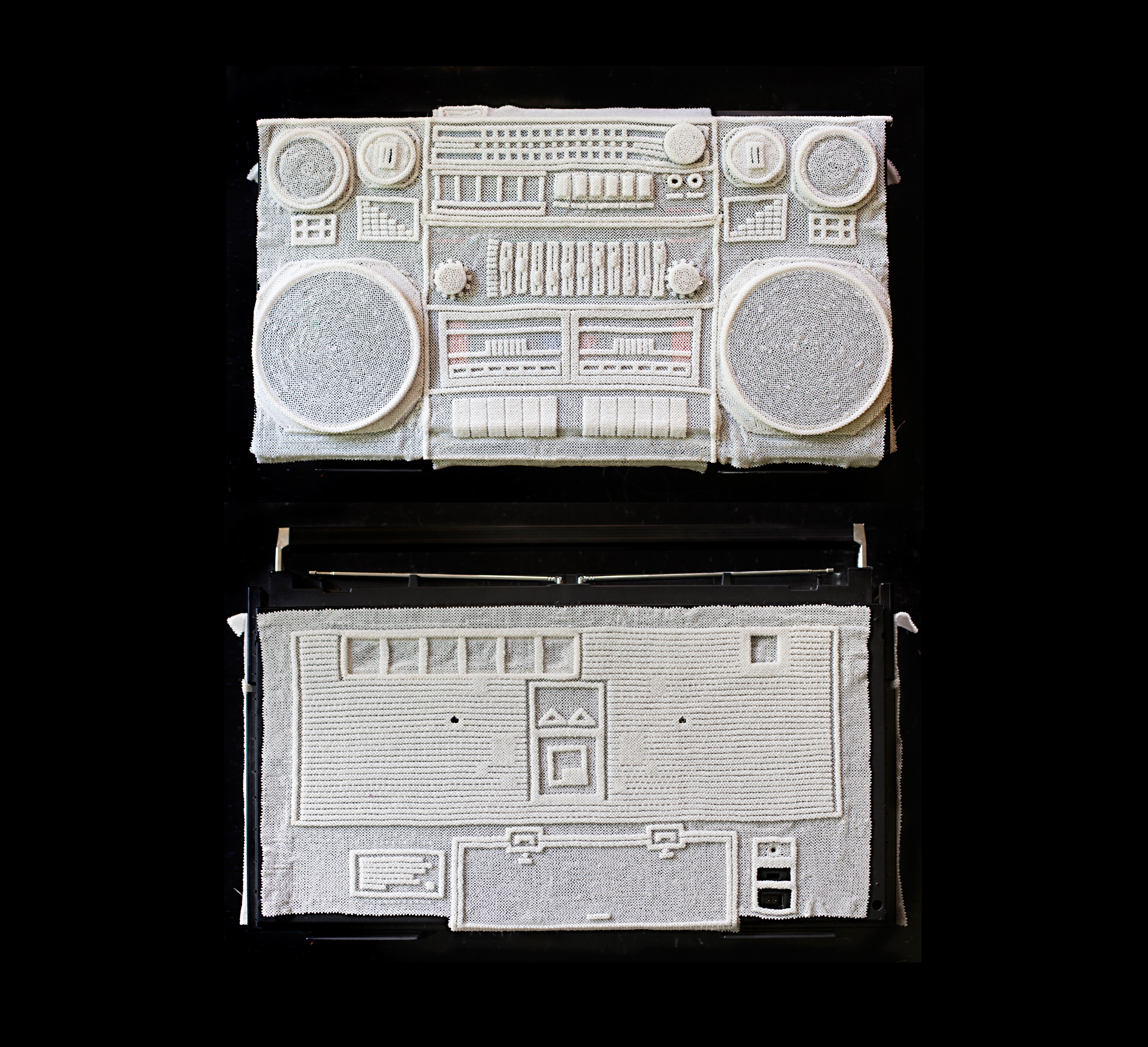

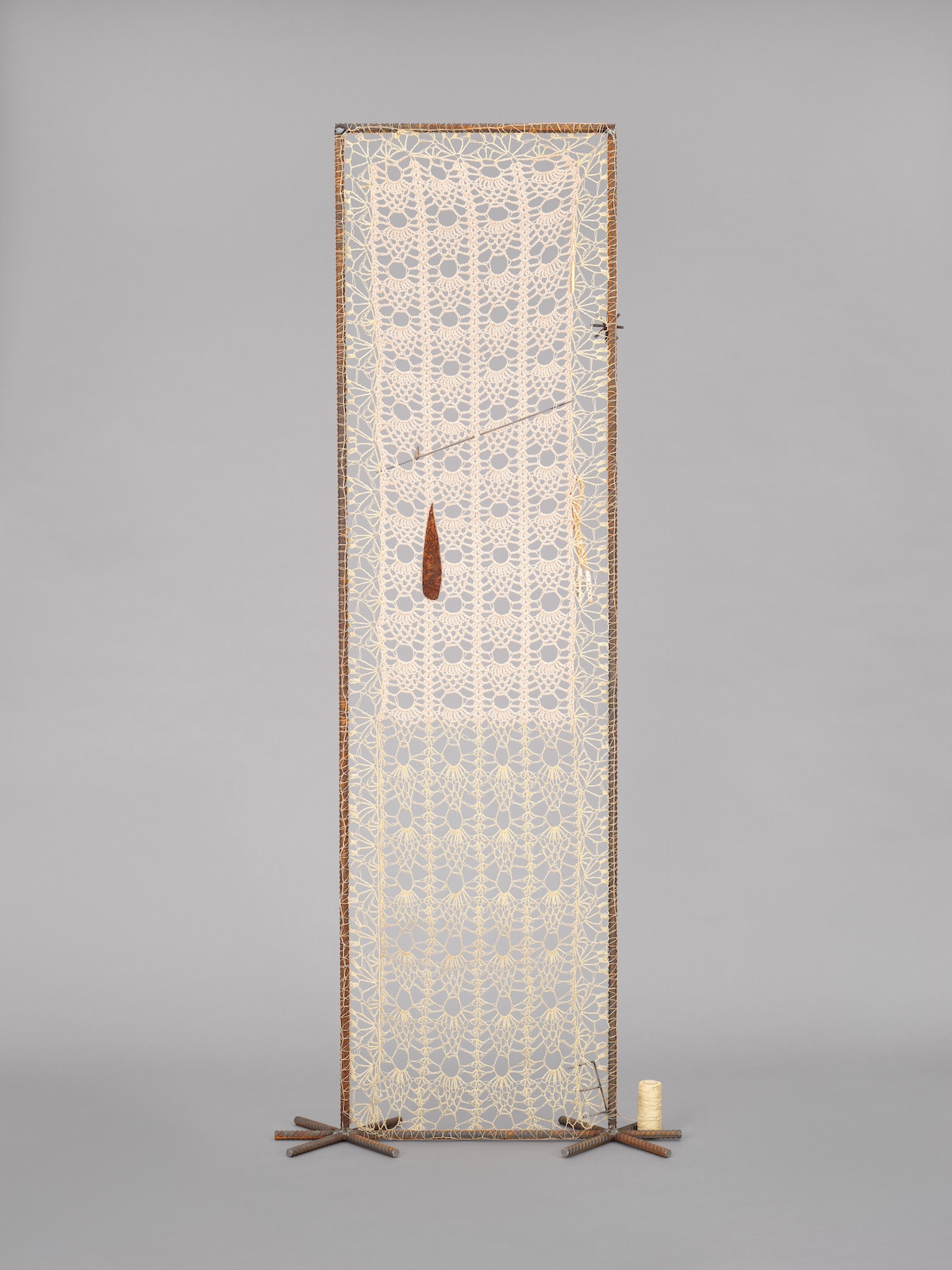

So, I wanted to use that in what I’m trying to convey with the work. Taking sometimes an overlooked object and recasting it in a way that people stop and consider it in a way they might not have is interesting to me. For example, If She Knew You Were Coming (2015) is a piece that was inspired by my mother. I think about who she was. She kept a nice house, she had a job, she was a nursing educator in several different ways, she loved to cook, to entertain, she introduced the world to my siblings and I by the meals she prepared. It was a creative outlet for her. Her kitchen was as much her studio as my studio is for me. I think about the role of women particularly in her generation and what was expected of them, and a lot of it was deadly dull tedium. I felt like there was a conversation between particularly that image and thousands of tiny white beads sewn onto the next. I think of how many lunches she packed, how many times she pushed the vacuum sweeper around. On top of the things she did in her professional life. I’m always looking for the perfect combination of image, concept, and technique. I feel like with the white pieces or colorless pieces or monochromatic pieces, I’ve been able to get a little closer to the perfect combination of those three things. It’s been exciting for me, I’ve enjoyed it. With this body of work, the sewing is as important as the glass beads, whereas in previous work they kind of obliterated that.

Thank you, that was a beautiful description. I definitely sense a narrative kind of something happening with the collection of works that I see. Is it that narrative that separates your work from something that is more decorative. The medium itself is widely thought of as decorative.

Oh, yeah, it's usually thought of as embellishment. When I started sewing things together it was not a fashionable medium. I remember somebody who I thought should know told me beads were not a medium with which art could be made. I did not agree. I was trying to find a place for my work and taking it around to different galleries, or just anybody who I thought would be able to advise me. Nobody said, Oh, this is a great idea. Except, perhaps, my parents.

As I began to work, there’s kind of a collective consciousness, and other people started to work, and books started to come out. People were interested in learning about it. I began teaching. I’ve taught quite a bit in my career. It was pretty evident to me early on that whatever direction I saw the trends going, I wanted to go in a different direction. I wanted to challenge the medium, and I wanted to advance it. I gave up things like sparkly beads and prints pretty early. It didn’t appeal to me. In effect, I’m using a layer of beads as a reductive medium rather than an added medium or an embellishment. I’m taking away rather than adding to. I hadn’t seen it done before, and I’ve been really interested in thinking that way. Looking for images that work, it’s harder than you think. Some things you cover with a layer, just 1/16th of an inch, and it obliterates the thing that would be recognizable about it. I don’t want the work to be purely sentimental. I want it to have a little bit of grit and tooth and interest. I want it to start a conversation. Some of the work is more successful at that than others. Like the boombox. There’s a certain amount of iconic quality to a boombox. People recognize and have an association with it. You don’t really look at a boombox, you just see it, you know what it is, you form that association. But when every detail has been worked through in this method, people stop and they tell me stories. It’s been really interesting to hear people react to the work.

How did you come to work with beads?

Well first you thread the needle; that’s my smartass answer. My father was a jewelry artist and he was head of an art department at a community college in Washington state for most of my growing up years. His name was Orville Chatt; he died about ten years ago. All of my siblings and I have a version of the house we grew up in. It was full of collections. He’d hang a shoe on the wall if it was interesting to him. And I have a shoe on my wall. I have a couple of them. Our walls and shelves were not covered with typical things. I grew up using my eyes that way.

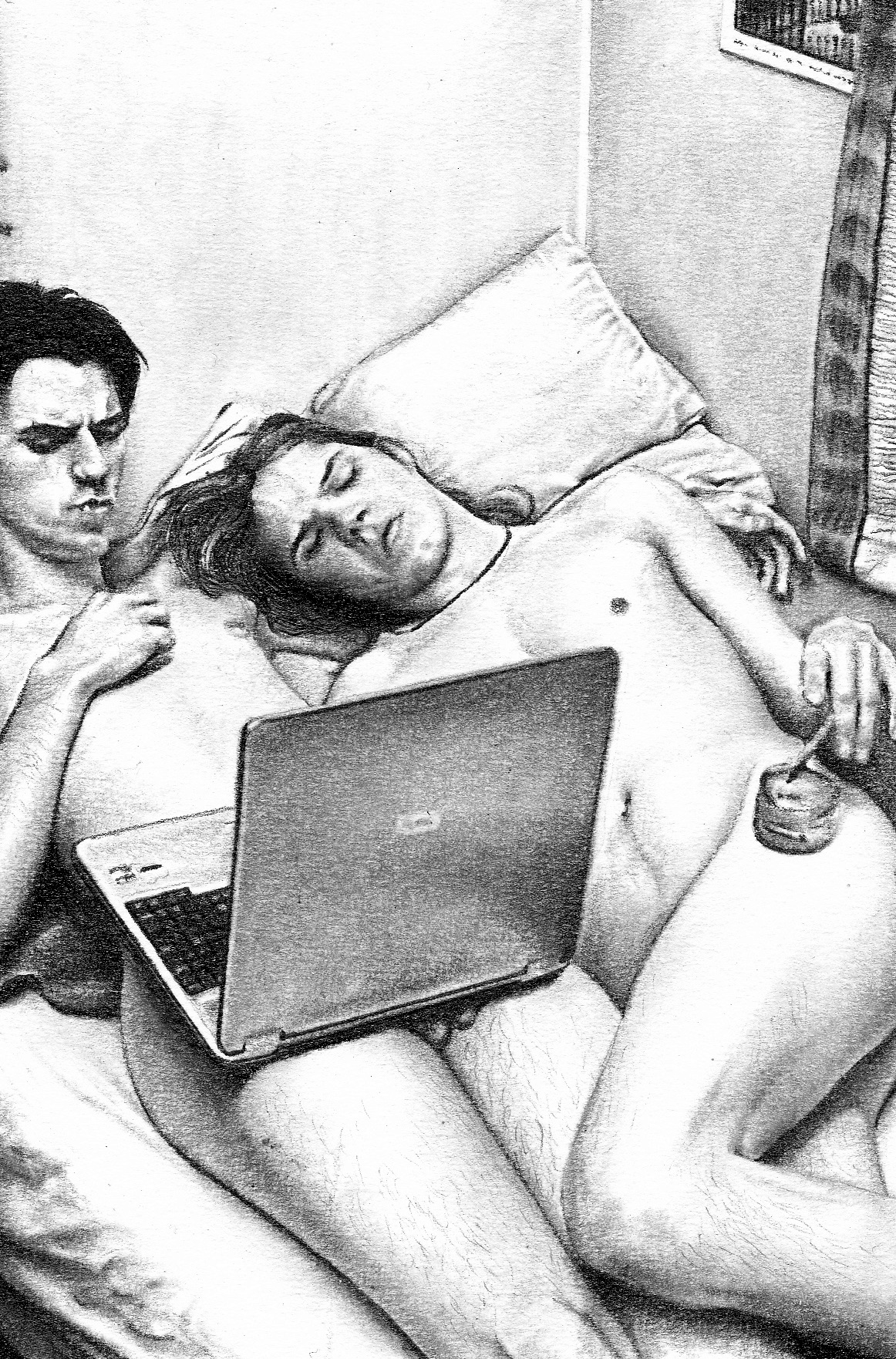

When he died, I inherited his beads. Not the same kind of beads I use usually. Oh my god, he had more beads than I do. It’s been interesting looking at that collection and trying to figure out what to do with it. But the apple didn’t fall too far from the tree. I actually started working with beads, and felt the spark, when I was probably about ten or eleven years old. I started sewing things together, nobody taught me how to do it. I figured out this little netting technique, and I could make little choker necklaces for anybody that would want them. It was exciting, I figured it out myself. They were pretty and I enjoyed making them. My immediate family enjoyed them, but people at school — it was a message that I got pretty early on that it was a medium that boys shouldn’t be interested in. I was much more concerned with fitting in then, than I am now. I put them away. I am a gay man, and I think a lot about some of the things I thought at that time. How gender roles are formed. So I also really enjoy the fact that I’m a 6’5’’ white guy that works in this medium that is covered in all kinds of tradition and all kinds of gender stereotypes. I enjoy that.

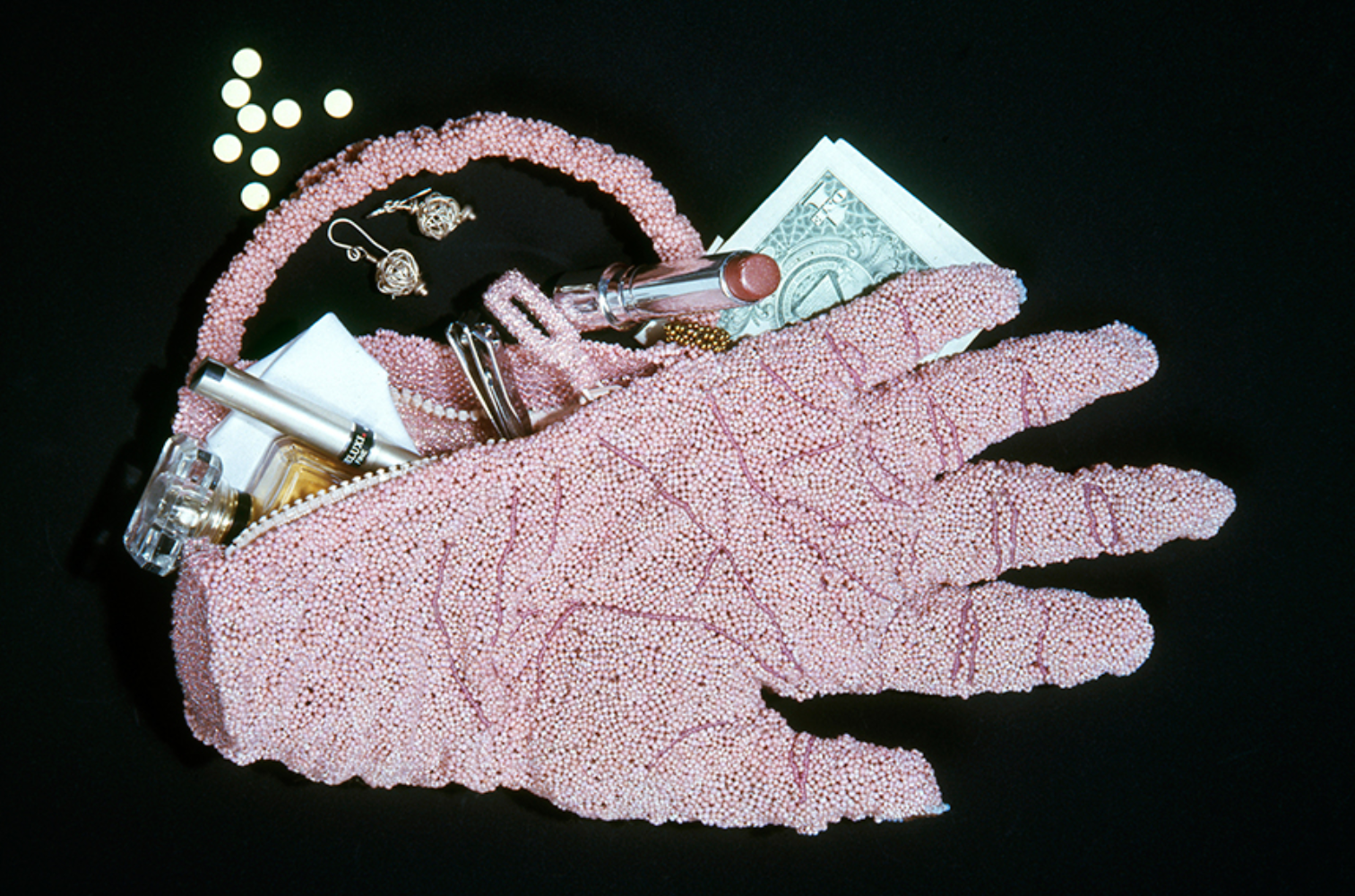

I was gonna ask you about the aspect of gender in your work because, like, the handbag for example: it’s just so coded to me. I don’t know, I wanted to know if you intentionally had a commentary on gender or how gender plays into your work.

I think it's inescapable.

Right.

When I think about who I am and the truths in my life that have followed me, I’m usually the odd person out. My degree is in apparel design, I was in a program with almost exclusively women. I’m often by myself. Much more often I’m working with women. When I teach, I’m the only guy. My life is full of irony. Some of that is inescapable in the work. I will say, Joyce Scott was another person who was there before I was, even. I wasn’t aware of her work when I first started, but once I did become aware of her work, it affected me. Because I saw how she was able to use her work to speak of her life. I remember thinking, like, I grew up in a middle class family, I’m white, I’m male, what do I have to talk about that’s interesting to anybody? But you dance with the person that brung ya, you know? I really want my work to reflect who I am, my life experience. I want my work to be true. I resist people telling me what I should think. I resist doing things I think will sell well. I mean I’m not opposed to it.

But it has to work for you.

I really make sure the work I do in my studio is what I want to be doing. I need it to be challenging, interesting to me. So, back to the handbag: a lot of my work starts out with a technical challenge. So that came from the figurative period. How can I use this medium to convey the human form? A hand is full of details. How do I make a fingernail look like it’s emerging from skin? How do I make creases? How do I make skin look like skin? A lot of that was a study. Then you’re working on it and thinking about what the image is. I rarely finish the piece that I begin. Sometimes I start out thinking of one thing, and then as I work on it, it becomes something else. Like I said, I have a lot of time to think about it. I was thinking about that. I thought about an old fox fur collar my mom had, and how grotesque it is to see a dismembered hand. She’d inherited it, she never wore it, it was her mothers. I thought it was just, you know, I am that kind of boy, so I thought it was as glamorous as ever. I couldn’t wait for her to wear it, and I was disappointed when she never did. As I get older, and I see that handbag, and I think about the fox fur, there’s a relationship between those two things. That’s part of what it meant to me. But it was also modeled after my hand, roughly. My work needs to reflect who I am.

That makes a lot of sense. I think your authentic connection with what you make comes through. Is there anything you’d like to add that we didn’t get to?

Well, I do love writing about my work. I’ve really enjoyed that part of my practice. If you look at my website, the major pieces have writing about them alongside.

If She Knew You Were Coming, the piece with the mixer. That’s not my mother’s mixer or cookbook, but those are things my mother had. Collecting the objects that worked together in a tableau. You have to curate that. I chose those things because they all remind me of my mother. Things a woman of her era would have. I made this piece in honor of her. You don’t always think of every aspect. When I put it out in the world, one of the first things I heard was that it was problematic because it was gender stereotyped. It’s a valid criticism, and it’s interesting to think about. And I have thought about it. And I defend it. Because to me, it is about the tedium of being cast in a certain role. She was capable of a lot of things, but she still made a home for us. She took it seriously, and she was a serious woman.

It goes back to speaking with an authentic voice. This piece was about my mother, it wasn’t about an ideal woman or an ideal mother. It was about my experience with my mother, and this is where she found her creativity. It was a tool she used that really broadened my world. You can read the full statement, but the people she invited to our table were not traditional people, often. And I am not a traditional adult. I think of who I am as an adult, and I know a lot of that is based on a vision for my life that I acquired by learning that people didn’t have to get married and there were people that traveled, and people that did all kinds of different interesting things. It was an education, a rich and valuable one. I have no problem with the image I created. I hope that the way I felt about it comes across, too. I think it does.

I totally agree. I don’t see that this is putting an ideal forward, or saying what a woman should be or anything like that. I feel like the personal aspect of it, the way that your work is so personal to you, really does come through.

I don’t mind if it's pretty if it works, but I also don’t mind making something that stirs something up inside of somebody.